A Paper Delivered at a meeting of the South Central Region of American Society for Eighteenth Century Studies conference

Grove Park Inn, Asheville, North Carolina, February 23-25, 2012 3-6, 2011. "'Terrifying Prospects & Psychological Landscapes -- Visions and Vistas of the Gothic ." Chairperson: David Macey. Panelists: Robert Kottage "Coining the Counterfeit: Truth and Artifice in Horace Walpole and his Castle of Otranto, J. David Macey, "Panoramic Vistas and Prospective Deaths: Mary Hamilton, Munster Village, and the Gothic Novel," Ellen Moody, "The Nightmare of History in Ann Radcliffe's Landscapes" [a change of title from program and original proposal] I publish the paper on this website to make the paper widely available, complete with scholarly notes and bibliography.“The Nightmare of History in Ann Radcliffe's Landscapes”

by Ellen Moody

From Piranesian Carceri and rat holes …

… here in Venice

The world's most louche and artificial city ...

Something profoundly soiled, pointlessly hurt

And beyond cure in us yearns for this costless

Ablution, this impossible reprieve ...

Lights. I have chosen Venice for its light,

Its lightness, buoyancy, calm suspension

In time and water, its strange quietness …"

Anthony Hecht, Venetian Vespers, 43-4, 47

Successful ridicule is powerful. Arguably, it caused Ann Radcliffe to stop writing novels and led to her nervous breakdown, and withdrawal from all public life despite these stunningly successful novels, sometimes credited with engendering the “extraordinary dream- and nightmare world of gothic romance” (Miles AR 26; e.g. Norton, 181-87, 219-23; Doody 552-53). She had showed how to evolve subjective narrative and project vast architecturally-organized landscapes and to marshall fast-moving vignettes within these from an indwelling consciousness (Scott 110, 118-19; Scott Critical Heritage 193; Wilson). Among her more specific achievements, her ability to evoke an imagined experience in a reader of an alluring visionary place1 had led her to create a Venice that has since been turned into the transgressive sexualized trope and dream-place of sorrow familiar to us all today (Paesaggi 120-32).

And yet, from 1797 on, near silence.3 For eight years she had endured harsh and catchy mockery (Rogers 3) and crude popular parodies (Barrett), and she saw her latest more controlled novel, The Italian (Conger), made no difference.3 As her husband understood, her inability to answer the continuing derision left her undefended against the increase of hilarity: she was described in the press as having gone mad from writing such books.4 And two hundred years later it is easy to find snide allusions to “Mrs Radcliffe” and Udolpho used as springboards for adverse criticism of female masochism, romance, gothic and historical fiction. Her books continue to be printed, and translated, suggesting a popular readership (however embarrassed). But in many literary histories, journals, encyclopedias and at conferences she is still alluded to in dismissive and even contemptuous language,.

I want to overcome the important intransigence of the published apparatuses of literary criticism (Finch 53-57) because the ridicule her memory has been subject to closes people's minds so they seem barely to read the passages in front of them. Readings which could change the way we view her are written half-apologetically (Bohls 106-7). I cannot avoid apology myself. Her texts contain conspicuous naiveties, risible anachronisms, and irritating rational explanations which I suggest are small marginal moments in the text found as frequently in other authors: the notorious incident of the veil behind which is a waxed replication of a corpse takes up six paragraphs altogether not in the same place against all of Udolpho (U 248-49, 432, 662).4 The real hostility to Radcliffe derives from social taboos which lead critics to turn away from and inoculate themselves all against her novels' depictions of open abjection and painful distress as when Emily cries in shattered ways at length. Radcliffe's gothics really read are embarrassing, threatening and disquieting.

In common with many writers of her generation, Ann Radcliffe consciously harnessed her experiences of intense emotional distress, which she had learned to overcome and control through minute exhaustive re-creations of what she absorbed from learned books and careful study of engravings. She is explicit about this in her fiction and non-fiction. For example, she tells us in Udolpho that after a traumatic night Emily “rose, and to relieve her mind from . . . ideas, that tormented it, compelled herself to notice external objects” and slowly to give words to a vivid minute picturesque vision (U 241). In Radcliffe's travel book's conclusion, she says that she took her journey, studied the books she did to visualize for us the buildings and places we have been in and has written what she has to “reconcile” herself to “human nature.” Her last sentence sums up A Journey Made in the Summer of 1794 as a book where she has been gladdened by grandeur and what evidence she found of honesty, friendliness and order (J 499-500). I read Radcliffe's works as displays of a continual process by which she transforms her experience of a marginalized self-protective life she did not otherwise admit to (but was well aware she was living) into poetic romances intended as effective proto-feminist and anti-reactionary contributions to her society. For Radcliffe “self-communication” and “self-preservation” became a mode of existence whereby she became productive and spoke to others (Wolf 89-90; Harding 11-12).6

My argument is Radcliffe's novels are serious political dystopias (Battaglia Paesaggi 41-69; Distopia Inglese 31-40).7 Since there are still critics who write about Radcliffe as if she were politically conservative (e.g., Durant), and thus bolster the common view of her – particularly socially unacceptable today -- as an elite Tory in retreat, and the two who've have written influentially on her Journey at most concede her a mild Whiggishness (e.g., Moskal), it's crucial to describe her Journey book and life-writing as a frame for reading her novels as Scott, Renwick and Sanna have done. Only recently has her non-fiction been gaining the separate respectful attention and praise it deserves (McMillan, Sanna, Bohls). Her biographers and critics (Miles AR 60-72; Norton 108-23) suggest in passing that in these she is intent to write anti-war and progressive arguments. She does so by describing landscapes which literally make visible recent historical catastrophes (like sieges), earlier and contemporary perverse social arrangements (of feudalism, in convents and monasteries), and architectural and “Druidical” (or neolithic) ruins (J 445-46). She shows us the remains of historical nightmares: hers is a landscape of memories.

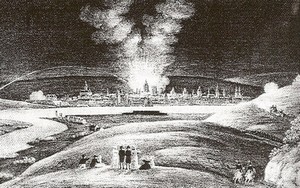

Radcliffe and her husband (who, perhaps using a modesty trope, she insists is a kind of co-author of her book's “political” explanations) are remarkably bold for English people writing in the 1790s (Norton 108-11; Miles AR 61-62). They provide an almost Keynesian analysis of class systems, showing how a lack of economic opportunity, freedom to move, to combine and associate with other people creates the poverty she records in Germany (Journey 152). Radcliffe herself detests all manifestations of war: Louis XIV emerges as a cruel monster repeatedly (355; see also 260, 272). She takes a Johnsonian attitude towards military heroes, presents dueling as murder. The whole of her long depiction (44 pages) of the Siege of Mainz, from the present ruined city, to the political lead into, the experience, and aftermath of the battles brings home to the reader the ravages the average person suffered and continued to suffer from the power-mad and vanity-led antics of the two “sides”; in her text war is not over when it's over (Journey 179-221).

To be able to offer some specifics, I compared Radcliffe's account to Arthur Chuquet's thorough scholarly monograph (based on Goethe's memoir and other documents). Radcliffe depicts the same siege (names the same people, focuses on the same political events, understands what was important) with the difference that she emphasizes not the fight, heroes and political leaders, but the civilian population, how the people were closely monitored and coerced into say producing such-and-such food; we see the sick, we experience the terror of people first encouraged to flee and then, finding themselves without entry into enemy territory, stuck on a bridge as open targets: two children went mad with fright. She does not grasp the 20th century view that the surrender of the place was not treachery but a remarkably iconoclastic (anti-military) brave act, but very unusually she does argue the city was never important commercially. She asserts that aristocratic cities become famous because admired, and their central habitats seem prosperous, but that does not mean most of the people are prosperous; she is therefore not surprised by the present desolate state of the place and predicts rightly that all the destruction she describes will not be remedied easily (220-21) We then move to her depiction of Cologne where we learn how despotism destroys commerce, how threats to a “free city” are inevitable when it is surrounded by militarist aristocracies (223-27).8

The political thought evident in the 1794 Journey lies behind the creation of Radcliffe's forbidding castles in all her books. A careful reader will notice brief political readings scattered in the fiction in fleeting remarks on the novels' places and spatial arrangements: for example, when Emily gets up close to Udolpho and passes through its “huge portcullis,” our narrator makes the point such a gate strikes Emily's thinking mind with “terror and dismay” (U 400). For elaboration we must turn to the non-fiction where the connections and implications we are meant to take away are realized explicitly. For example, when approaching the ruins of Brougham Castle, Radcliffe writes:

Some of the walls remaining are twelve feet thick, and the places still visible, in which the massy gates were held to them by hinges and bolts of uncommon size. A fuller proof of the many sacrifices of comfort and convenience, by which the highest classes in former ages were glad to purchase security, is very seldom afforded, than by the three detached parts still left of this edifice; . . . they exhibit symptoms of the cruelties, by which their first lords revenged themselves upon others the wretchedness of the continual suspicions felt by themselves. Dungeons, secret passages and heavy iron rings remain to hint of unhappy wretches, who were, perhaps, rescued only by death from these horrible engines of a tyrant's will. The bones probably of such victims are laid beneath the damp earth of these vaults (427)

I also compared her trip through Cumberland and Westmoreland to Gilpin's travel book by which she was influenced (Kostelnick): while Gilpin's descriptions are interwoven with aesthetic theory, hers are with comments on political arrangements. Her imaginative re-creation of Furness Abbey has been much praised, but not mentioned is the conclusion where she describes the impoverished and repressed lives of those who lived in such a place (enforced silence most of the time was the rule), the tyranny of its aristocratic lord, his super-rich income for the era, and then drops down to a quick recounting of his swift surrender to Henry VIII and acceptance of a position as “Rector of Dalton, a situation then valued at thirty-three pounds six shillings and eight-pence a year” (Journey 496). Radcliffe's has a dry wit.

Radcliffe's travel-writing may also be set profitably in the context of that of other women and romantic writers. Her strong tendency (similar to Mary Wollstonecraft) is to take what has been called “a masculine position” (Mills 19-26), that of the impersonal gazer who does not describe herself as a figure in the landscape but analyses large general invisible forces. Like Mary Godwin Shelley (Kautz), Radcliffe is seeking health, and on the hunt for evidence of social progress and prosperity, which she is gladdened to find in Holland, and in some parts of the Lake District, though generally not in Germany (but see Journey 398). Her political views in passages of description is close to that of Helen Maria Williams (Jones). By contrast though Radcliffe is pessimistic about the capacity of people to divest themselves of “superstition. ” She stresses egoistic outlooks and shows the human penchant for violence; she argues that instances of “gallantry” are forms of “public encouragement of a disposition to violence,” 270, 434). We are shown the ruthless violence of those in power (143), how easy it is for people to destroy other people's property, especially once the situation is declared “war” (218); and she suggests at one point that common spoken adherence to a work ethic is often cant (219).9

She also tells funny prosaic stories to exemplify human manners and succeeds in making the ordinary people she meets come alive. McMillan has emphasized Radcliffe's stories of where she is moved “by the genuine good will and friendliness of the local people; records the voices of singing children; the farmer working side-by-side with his hands;” we see her attempt to help an aging guide, watch her eat what we would call a vegetarian meal, the usual preserved fruit and cream common in the novels, only here she once again makes her outlook explicit: “an innocent luxury, for which no animal has died” (McMillan 60-61).10 McMillan omits the less pleasant stories, as when there is no institution or direct self-interest to control people (219) she cannot manage to buy a book which exposes the truth of a local siege (219). Several incidents are transmuted into the striking gothic figures and stories of the novels (Journey 112). At one point, Radcliffe says the “conversation [of “persons of learning, or thought”] has no influence upon the community; their works cannot have a present, though they will have a general and permanent effect [later].” This introduces an argument that the extreme poverty we have just seen in peasants as an aftermath of war fails to teach anything helpful. No one can visually see that this poverty is the result of “desperate exercises of policies;” all that is visible are “debased” peasants deprived of “pride.” The result: all parties soon join to renew war which brings about “injurious effects” upon regions elsewhere (342-43).

I have recorded the explicit insights in Radcliffe's non-fiction as these support my reading of her romances as ancien regime allegories of a society which fosters dysfunctional socializing, sadism, violence, lying, obduracy, and, as a way to recover or exist, solitude (Battaglia, Distopica Inglese 32). Like many others in the 1790s she meant to write critiques of her society (Paulson); in her case she found safety by setting them in a depiction of the ancien regime as an imagined feudal past in Europe. Like modern historical fiction writers (Groot), she creates her own usable past. In The Romance of the Forest she exposes the practices of the ancien regime from lettres de cachet to unjust imprisonment and courts, debtors' prisons (RF 311-12), and inhumane arrangements. She exposes the fallacies of medicine as well as how disregard for someone based on their lack of rank endangers their lives (RF 183-85). Udolpho goes further to use the feudal past to show the need all people have for orderly laws, marketing customs, and safe public thoroughfares. A typical moving minor story is about a servant, Theresa, thrown out of her cottage when Emily's uncle takes it upon himself to try to sell her property; we see Emily's grief for Theresa when she comes upon Theresa in a hovel; her uncle is within his rights. Only at the close of Udolpho when Emily returns to La Vallée and finds that Theresa has been helped by Valancourt (U 627-28) and Emily has gained control of her inheritance, can she restore Theresa to comfort. A parallel for this story occurs in Radcliffe's 1794 travel book where Radcliffe comes upon a shoeless, stockingless old woman terrified of her employer and landlord (Journey 260). Servants in Radcliffe are not invisible. Radcliffe's banditti under the leadership of Montoni are not used absurdly and for aesthetic affect. They are marauding bands of thieves, murderers and rapists (though this latter word is avoided). In The Italian Radcliffe famously turned her attention to the Inquisition, the coerced and repressed life of convents (also dealt with at length in Cologne in the Journey book, 109-15); and the control of minds through the use of religious confession, solitary imprisonment and torture (I, Clery Introd xv-xvi, xx-xxvii).

One inference from Radcliffe's texts readers seem blind to in her case (though they are willing to grant this other 18th century women novelists) is an exposure of family pathologies, wife abuse, permitted brutality and obdurate cruelty. Radcliffe shows us how family marital aggrandizement threatens her heroines, and focuses on how all sorts of arrangements show that women are answerable to men and their family and communities with their bodies; Radcliffe's emphasis on locks which prevent the heroine from keeping others out yet shut her in symbolize how she cannot control what space she is in or who she is with. The point is emphatically made in Udolpho that Emily would have been relatively safe (no one is safe under ancien regime law) if she had eloped with Valancourt. In the final proposal scene between Emily and Valancourt in the novel's penultimate chapter Emily recognizes she has been wrongly misled by slander her family were eager to believe (U 667-69). She is less ambivalent about her aunt's advice than Austen's Anne Elliot is towards Lady Russell in a closely parallel scene at the close of Austen's Persuasion (P 246). In The Italian Ellena Rosalba defies the Abbess in another parallel scene in Austen, that of Elizabeth Bennet defying Lady Catherine de Bourgh. Unlike Austen, Radcliffe makes her protest on behalf of a woman's rights the point:

Her judgment approved of the frankness, with which she had asserted her rights, and of the firmness, with which she had reproved a woman, who had dared to demand respect from the very victim of her cruelty and oppression. She was the more satisfied with herself, because she had never, for an instant, forgotten her own dignity so far, as to degenerate into the vehemence of passion, or to faulter with the weakness of fear. Her conviction of [the Abbess's] unworthy character was too clear to allow [Ellena] to feel abashed in her presence (Conger 138)

Radcliffe's novels' paranoia is the understandable result of real persecution rooted in struggles for money, estates and power. Central is her female characters' condition of dependence.

I turn to but one series of visions. I focus on The Romance of the Forest, set in 1764, the year Radcliffe was born, as the most candid of them. The first volume contains a fictionalized displacement of Rictor Norton's biographical conclusions that as a child Ann Radcliffe was sexually abused by her father and not protected by her mother.11 At the volume's close, the narrative suddenly erupts with a series of terrifying bloody nightmares that re-enact the configurations of the losses, violence, and violations the fiction has been dramatizing (RF 107-10).12 We then move through a trajectory where Adeline gradually uncovers her past in the context of a deft depiction of ancien regime customs and laws, a debate between an intendedly Rousseauistic view of human nature as capable of good and disinterested action and a group of what I'll call Sadeian stock-in-trade positions on the pathological nature of nature (Clery Radcliffe and de Sade 204). This is followed by flight seen as strength, an important lesson the heroine learns in all three novels. Upon reaching the haven, here Languedoc, the text turns heuristic as Adeline gradually calms, exerts control over herself within a sympathetic community, and Radcliffe writes the visionary rapturous landscapes she is so famous for. I quote just very end of one that combines the evening visions of Richard Wilson (1713-82) and Claude Vernet (1714-89); Radcliffe as Adeline also anticipates John Crome (1768-1821) of the Norwich School, especially his use of light in Evening Yarmouth Harbour (1817):

She continued to muse [“in the anguish of her mind”] till the moon arose from the bosom of the ocean, and shed her trembling lustre upon the waves, diffusing peace, and making silence more solemn; beaming a soft light on the white sails, and throwing upon the waters the tall shadow of the vessel, which now seemed to glide along unopposed by any current [in] the silence of the hour ... (RF III:295; see also 297)

It is crucial to divest from our assumptions two hundred years of disrespect for Ann Radcliffe's mind and art. We need to re-formulate our perspectives on Radcliffe and we need to be frank. We should not begin with the conventional search for historical pictorial analogues for Radcliffe's fictionalized vistas but end there.

Ellen Moody

Alexandria, Va

1 But see Miles in “The 1790s.”

2 These often from sheer hard study and her memory of reading learned and popular tomes. The many sources that go into Radcliffe's works and the intense examinations and study she practiced (commented upon numerous times by her husband) are only beginning to be done justice to. A number of essayists, including those not explicitly on Radcliffe in La Questione Romantica bring this home to the reader: Ascari, Battaglia, Scrittori, Guerra are the most striking. We have got to go beyond her reading of Burke's Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757); Hester Thrale Piozzi's travel book, Observations and Reflections Made in the Course of a Journey through France, Italy and Germany (1789); and Gilpin's tour books and “Three Essays on Picturesque Beauty (1795).

3 1797 was the year she published a guarded gothic, The Italian, where she placed a male consciousness at its center (probably her most read and the only romance by her to have thus far been directly filmed). She came near to publishing Gaston de Blondeville (Norton 193); she did publish her poems (1815, 1816). The film is a French mini-series, Le confessional des penitents noirs. There is a modern French translation of The Italian by Fournier with the same subtitle marketed in modern French bookshops. I suggest her books have has been indirectly filmed in several Austen films, the 1987 and 2007 BBC gothicized Northanger Abbeys, the 1995 romantic and Brontesque Miramax and 2008 BBC/WBGH Sense and Sensibilities. The 2005 Universal Lawrentian Pride and Prejudice.

4 William did understand and moved quickly after his wife's death to publish a strongly decorous memoir by carefully-picked sympathetic scholarly lawyer, Thomas Noon Talfour. Norton 244-49.

5 Radcliffe's explanation at the book's close that such wax figures were historically used as a form of emotional torture is of course ignored; Castle's argument that the waxed figure are part of a skein of imagery making it difficult to distinguish life from death has made some inroads (Castle 241-47);

5 See Zimmerman.

6 Radcliffe and her husband were well aware of what they were revealing about the nature of her life when in Talfourd's memoir he tells of how William would come home very late at night to find she had produced copiously from her reading and contemplation for hours a day and night at home with no other call on her time. In “Culture is what you experience,” Wolf describes an analogous trajectory for Henrich von Kleist (1777-1811) and Karoline von Gunderrode (1770-1804); Harding's famous “Regulated hatred,” outlines in Austen an analogous imaginative resort into irony.

7 Battiglia's study of Margaret Oliphant's Dantesque ghost story, “The Land of Darkness”shows what I would call Radcliffe's methodology. Oliphant's pages on Radcliffe in Oliphant's history of 18th century literature show Oliphant studied Udolpho carefully and understand it acutely (Lit Hist II:232-39). Sanna makes a persuasive care for dating the Lake District part of Radcliffe's book as made up of several different journeys, some occurring much earlier than her 1794 summer, and some the result of memories of her travels as a girl to see (for example) Hardwick castle. Norton agrees, 180.

8 My comparison cannot go into the full account she provides. Other long sequences of description in the book I hope to go into eventually come from her extensive reading in learned architectural, historical, and chronicle works as frameworks for her descriptions of several abbeys, the lives live there, and the history behind ruins of castles. The background to this book includes the immense 3-volume Antiquities of Furness Abbey (1784) (see Lui), and the 3-volume History of the Abbey of St Albans by Peter Newcome (1793)

9 Mills, Jones, Kautz and McMillan below are all in the excellent anthology by Gilroy. Renwick from a general historical perspective also shows strong respect for Radcliffe's travel book and reads her gothics in its context, 81-85. Levy (33-55) makes the case that an important source for the gothic are the cathedrals and other gothic ruins left in the UK and elsewhere.

10 Radcliffe's concern for animals is another aspect of her sensibility which is plainly there and overlooked; she reminds me of Southey in his Letters from England (88, 141).

11 e.g., Three times Adeline, the heroine repeats a version of a phrase that resonates deeply: how terrifying it is to be "betrayed by those [you] depend upon." She is first seen traveling with and in dread of thug strangers (d'Aulnoy and his brother, Du Bosse) to whom her apparent father, Louis de St Pierre, handed her over, to do with as they wish; as in the tale of Snow White, they are reluctant to murder Adeline, and in turn give her to a man encountered on the road who is fleeing gambling debts. Pierre de la Motte, a brilliantly conceived and complicated character (Popal), comes gradually to function as her equally reluctant protector. His wife who assumes the mother position, Madame de La Motte, jealous of her husband's attraction to Adeline, turns cold to her, will not nurture, hardly listens, will not protect her.

There is also an obsessive-repetition pattern in the three famous novels. Freud suggested this kind of behavior is a response to what is felt as violation-trauma. You attempt to control the hysteria by carefully repeating a routine -- over and over again. I find the obsessive repetition disjunctive pattern in Radcliffe comes out in all sorts of ways. The labyrinth that doesn't quite make sense. It's all in a mist; door after door from corridor after corridor: like a rat in a maze which is only glimpsed partially. This is seen most graphically in much of the action of Radcliffe's first genuine attempt at a gothic, A Sicilian Romance: characters hurry along from gallery to gallery, each with its doors which have to be got through; then pass into labyrinth after labyrinth only to find themselves in front of yet more doors, which have to be got through; then into the recesses of cavern after cavern, dungeon after dungeon, with yet more doors, only to be confronted by a back stairway (back of what?) which leads out to somewhere underneath a dusky sky and a horizon which extends into infinity. They take another rushed turn through a Salvator Rosa painting only to end up in another dungeon and begin the same dizzying journeys into the recesses of the mind again. It's like being in an endlessly circuitous Piranesi painting, moving through (to allude to Oliphant) a land of darkness. One could give a very turn to the autobiographical background, and for example, examine the supportive mother-daughter patterns in the way Susan Greenfield does, but the overall nature of the fiction would remain the same.

12 The equivalent moment in Udolpho occurs at the center of the castle sequence where Emily de St Aubert grieves intensely, isolated bereft of a deeply congenial (equally sensitive and thoughtful) father, dependent on another cold aunt-mother, a morally obtuse and stupid woman, Madame Cheron, who marries a dark antagonistic father-lover (the Marquis Montoni), Emily's response is to cry literally and at length, and in ways that are highly individual. Emily's crying is not presented in stylized language nor does it occur in a cliched melodramatic vignettes. Emily really cries, and cracks up as a attered and then silent (she moves into oblivion) consciousness when she cannot escape her room; then when she does escape, instead of experiencing nightmares, she comes across real livid corpses (U 348), and eventually witnesses her aunt-mother (in effect) murdered, and is beset upon in her room with its unlockable door by threats of abduction and implied rape by men Montoni has invited into Udolpho (e.g, U 260-63), scenes which anticipate the memorable scene in The Italian where the heroine, Ellena Rosalba nearly knifed to death by Schedoni, her biological monk. Poovey produces a nuanced reading showing that Radcliffe brought out “terrifying implications” in her analysis of “the economic aggressiveness currently victimizing defenseless women of sensibility,” but retreated from her own conclusions because of her investment in sensibility values, 311. But she has not read either the 1794 Journey or journals.

Bibliography

Austen, Jane. The Novels of Jane Austen. Ed. R. W. Chapman. 3rd Ed. Oxford: OUP, 1033-69.

Barrett, Eaton Stannard. The Heroine (1813). Introd. Michael Sadleir. New York: Stokes, 1927.

Battaglia, Beatrice. “La scrittura fantastica contro I misfatti della ragione” and “L'allegorica dell'individualismo borhese in 'The Land of Darkness” di Margaret Oliphant,” La Critica alla Cultura Occidentale nella Letteratura Distopica Inglese. Ravenna: Longo, 2006. 9-14, 31-40. Distopica Inglese.

----------------------. Paesaggi e misteri: Riscoprire Ann Radcliffe. Napoli: Liguori, 2008. Paesaggi.

Bohls, Elizabeth. Women Travel Writers and the Language of Aesthetics, 1716-1818.

Chuquet, Arthur. The Wars of Revolution: VII: The Siege of Mainz and the French Occupation of the Rhineland, 192-1793, trans and annotated by Wm D. Peterson. West Chester, Ohio: Nafziger, 2006.

Clery, E. J. “Ann Radcliffe and D.A.F. DeSade; thoughts on heroinism.” Women's Writing, 1:2 (1994):230-14. “Ann Racliffe and DeSade.”

Conger, Sydney. “Sensibility Restored: Radcliffe's Answer to Lewis's Monk. Gothic Fictions: Prohibition/Transgressions. NY: AMS Press, 1989. 113-49.

Doody, Margaret Ann. “Deserts, Ruins and Troubled Waters: Female Dreams in Fiction and the development of the Gothic Novel.” Genre, 10 (1977):529-72.

Durant, David. “Ann Radcliffe and the Conservative Gothic.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, 22:3 (2003):519-30. He shows no knowledge of Radcliffe's 1794 Journey.

Finch, Annie. The Body of Poetry: Essays on Women, Form and the Poetic Self. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2005.

Freud, Sigmund. “Mourning and Melancholia (1917), General Psychological Theory, ed. Philip Rieff. NY: Simon & Shuster, 1991. 164-79.

Gilpin, William. Observations on Cumberland and Westmoreland. 1786 rpt. NY: Woodstock, 1996.

Gilroy, Amanda, ed. Romantic geographies: Discourses of travel, 1775-1844. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2000. Sara Mills, “Written on the Landscape: Mary Wollstonecraft's Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark,” 19-34; Dorothy McMillan, “The secrets of Ann Radcliffe's English travels,” 51-66; Chris Jones, “Travelling hopefully: Helen Maria Williams and the feminine discourses of sensibility,” 93-108; Beth Dolan Kautz, “Spas and salutary landscapes: the geography of health in Mary Shelley's Rambles in Germany and Italy,” 165-81.

Greenfield, Susan C. “Veiled Desire: Mother-Daughter Love and Sexual Imagery in Ann Radcliffe's The Italian.” The Eighteenth Century, 33 (1):1992.

Groot, Jerome de. The Historical Novel. London: Routledge, 2010.

Harding, D. W. Regulated Hatred and Other Essay on Jane Austen, ed. Monica Lawlor. London: Athlone Press, 1998. 5-26.

Hecht, Anthony. The Venetian Vespers. NY: Atheneum, 1984 Hogle, Jerrold E. The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction. Cambridge UP, 2002 E. J. Clery, “The genesis of “Gothic fiction” 21-39; Robert Miles, “The 1790s: the Effulgence of Gothic” 41-62.

Kostelnick, Charles. “From Picturesque View to Picturesque Vision: William Gilpin and Ann Radcliffe.” Mosaic: a journal for the comparative study of literature 18 (1985):31-48.

La questione romantica, 15-16, “Viaggggio e Paesaggio,” Autunno 2003 – Primavera 2004: Maurizio Ascar, “Landscape and Imagination: the Italian mountains in romantic travel writing,” 15-16; Francesca Lui, “Transiti: Note sul pittoresco in Francia tra Sette e Ottocento,” 29-44; Beatrice Battaglia, “The Politics of Narrative picturesque: Gilpin's Rules of Composition in Ann Radcliffe's and Jane Austen's Fiction, 45-56; Anna Rosa Scrittori, “The Language of Landscape in Ann Radcliffe's Novels, 57-68; Lia Guerra, “Wandering Women: Female Travel Writing as Dynamic Space: the Evolution of a Genre, 107-18.

Le Brun, Annie. Les chateaux de la subversion. Paris: Garnier, 1982.

Le confessional des penitents. Dir. Alain Boudet. Writer. Marcel Moussy. Perf. Pierre-Francois Pistorio, Maurice Garel, Aniouta Florent. French TV mini-series, 1977.

Levy, Maurice. Le Roman 'gothique anglas, 1764-1824. Paris: Albin Michel, 1995.

Miles, Robert. Ann Radcliffe: The Great Enchantress. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1995.

McMillan, Dorothy. “The secrets of Ann Radcliffe's English travels,” Romantic geographies: Discourses of travel, 1775-1844, ed. Amanda Gilroy. Manchester: Manchester U P. 51-76

Moskal, Jeanne. “Ann Radcliffe's Lake District.” Wordsworth Circle 31:1 (2000):56-61.

-------------------. “Cleanliness, Dirt and Nationalism in Ann Radcliffe's Dutch Travels. ” European Romantic Review 12:2 (2001):216-25.

Norton, Rictor. Mistress of Udolpho: the life of Ann Radcliffe. London: Leicester UP, 1999.

-----------------, ed. Gothic Readings: The First Wave, 1764-1840. London: Leicester UP, 2000.

Oliphant, Margaret. The Literary History of England in the End of the Eighteenth and Beginning of the Nineteenth Century, 3 vols. London: Macmillan, 1889.

----------------------. “The Land of Darkness,” in A Beleaguered City and Other Tales of the Seen and the Unseen, ed. Jenni Calder. Edinburgh: Canongate Classics, 2000. 313-62.

Paulson, Ronald. “Gothic Fiction and the French Revolution,” ELH 48:3 (1981):531-54.

Poovey, Mary. “Ideology and 'The Mysteries of Udolpho.” Criticism, 21:4 (1979):307030.

Popal, Miriam. “On The Romance of the Forest by Ann Radcliffe and Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen,” A Student Journal Essay, Gothics, ghosts, and and l'écriture-femme. Ellen Moody's website. July 14, 2000.

Radcliffe, Ann. A Journey Made in the Summer of 1794, through Holland and the Western Frontier of Germany, with a Return down the Rhine, To which are added Observations during a Tour to the Lakes of Lancashire, Westmoreland, and Cumberland. Elibron Facsimiles, 1975. Journey

------------------. A Sicilian Romance, ed. Introd. Alison Milbank. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1993. SR -

-----------------. Gaston de Blondeville, or the Court of Henry III. Keeping Festival in Ardenne, a Romance. “To which is added a Memoir of the Author, with extracts from her journals” [by Thomas Talfourd Noon]. 2 Vols. 1826; rpt. NY: Arno, 1972. GB ------------------. L'Italien, ou le Confessional des Penitents Noirs, trans. N. Fourier, introd. Tony Cartano. Paris: Presses de la Renaissance, 1977. 31-68. I

------------------. The Mysteries of Udolpho, ed. B. Dobree, introd. & notes Terry Castle. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1998. U

------------------. The Romance of the Forest, ed., introd. Chloe Chard. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1986. RF

Renwick, W. L. English Literature, 1789-1815. Oxford: Clarendon, 1963. 80-89.

Roger, Deborah D. ed. The Critical Response to Ann Radcliffe. Westport, Conn: Greenwood P, 1994.

Russ, Joanna, “Somebody's Trying to Kill Me and I Think It's My Husband” and Kay J. Mussell, “'But Why Do They Read Those Things,” The Female Gothic, ed. Juliann E. Fleenor. Montreal: Eden Press, 1983.

Sanna, V. “La datazione del libro di viaggi di Ann Radcliffe.” Critical Dimensions: English, Germand and Comparative Literature Essays in Honour of Aurelio Zanco, edd. Mario Currelli and Alberto Martino. Cuneo, Italy: Saste, 1978. 291-312.

Scott, Walter. On Novelists and Fiction, ed. Ioan Williams. NY: Barnes & Noble, 1968.

Southey, Robert. Letters from England. London: Cresset, 1951. Wilson, A. N. The Laird of Abbotsford. Oxford: OUP, 1989. Wolf, Christa and Jeannette Clausen, “'Culture is what you experience:' An Interview with Christa Wolf,” New German Critique 27 (1982):89-100.

----------------. No Place on Earth, translated from the German by Jan Van Heurck. NY: Farrar: Strauss, Giroux, 1982.

Zimmerman, Sarah M. “'Does thou not know my voice?': Charlotte Smith and the Lyric's Audience,” Romanticism and Women Poets: Opening the Doors of Reception, edd. Harriet Linkin and Stephen Behrendt. Lexington; Kentucky UP, 1999. 101-24.

Home

Contact Ellen Moody.

Pagemaster: Jim Moody.

Page Last Updated: 11 March 2012