[The following is the original longer version of a review published in the Keats-Shelley

Journal, LIV, 2005: 199-202.]

Child Murder and British Culture, 1720-1900. By Josephine McDonagh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. Pp. xiii, 278. $65.00.

Fatal Women of Romanticism. By Adriana Craciun. Cambridge Studies in

Romanticism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. Pp. 328. $65.00.

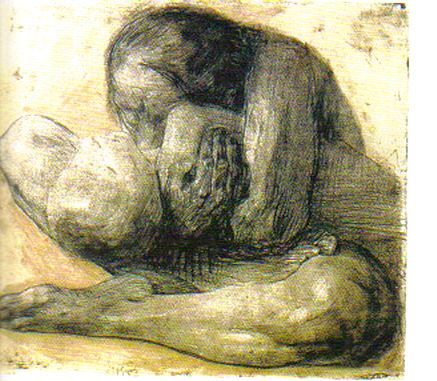

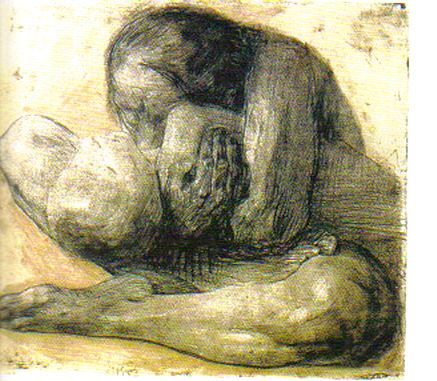

McDonagh's and Craciun's books, thought-provoking, well-researched, and packed with close readings, are rooted in the same psychological and social terrain as Hill's novella. McDonagh's book is a postmodern history of how child murder has been used from the early 18th to the late 19th century in England and the Commonwealth. In most cases of infanticide, strikingly similar, contradictory and unprovable evidence as well as the self-interested opaque ways of accounting for what happened have made it impossible to glean what actually occurred or why (p.1). Therefore, she tracks motifs to show that they are not, as commonly supposed, devoid of meaning, an expression of nihilism (p. 8), but reveal an acceptance of the murder of new-born and unwanted children on Ernest Renan's grounds: the building of a stable society and shared culture depend the enactment and erasure from public memory of violent acts (pp. 130-31). Such sites function as lieux de mémoires where behaviors, rationalized norms, and assumptions about human nature fundamental to the structuring of even all societies are formulated, tested, and contested (p. 12).

Craciun argues that depictions of violent and fatal women are figural eruptions women profit from and enjoy. Building on 20th-century treatises which challenge binary perspectives on male and female sexuality, interrogate texts endorsing ethical accounts of society, and valorize pornography for women (e.g. Terry Castle's Masquerade and Civilization and Angela Carter's The Sadeian Woman), Craciun affirms that women are no more benevolent or nonviolent than men (pp. 57-8, 71, 154). Her subjects are later 18th-, through early 19th-century women who committed violent acts, broke taboos, wrote about violence, and longed openly for sexual fulfillment, vatic status, and death; women whose fates were determined by their having to submit their bodies to manipulative (and when they disobeyed) punitive social customs. She uses Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Robinson, Judith Butler and Susan Bordo's books to exemplify intelligent attempts to change the processes whereby women's bodies are debilitated and gendered female through debasement.

McDonagh analyzes a vast array of texts in a post-colonialist framework.. For the 18th century she draws upon Scottish and French enlightenment philosophers, historians, economists, and physicians; plays performed in the London theatre (e.g., Richard Glover's Medea, 1767); abolitionist and progressive tracts; travel literature; novels; satires and later 18th-century Jacobin and anti-Jacobin verse, including (notably) Swift's "A Modest Proposal;" and the surgeon William Hunter's medical tract, Uncertainty of Signs of Death in a New Born Infant (1784). For the 19th, she includes romantic verse (Wordsworth's The Thorn and Blake); and, contextualized by references to urban harsh social and economic conflicts and fears, dominant (Malthus's Essay on the Principle of Population and the popular 'Marcus' pamphlets, ca. 1830s-40s) and derivative tracts (Edwin Chadwick's The Practice of Interment in Towns, 1843); fiction (Dickens's The Chimes, Eliot's Adam Bede, Hardy's Jude the Obscure); plays, stories, and tracts by women (often by feminists or women identifiable as radical, secularist, and sympathetic to the eugenics movement); Irish stories and tracts; and English tracts about the Irish using mythic beliefs and stories, all of which persistently focus on child-murder in Ireland.

McDonagh's sombre book alerts us to how often child murder is a pivotal event or accusation in obsessive public controversies and macabrely fascinating and notorious pamphlets and books (pp. 24, 65). She discerns a muted recurrence to a civic humanist idea of child sacrifice as an acceptable act (pp. 22, 48, 54). William Hunter's text is important because, from 1624 until 1803, and (despite changes in the law) for long afterwards, if an unmarried mother could be accused of concealing her pregnancy or the childbirth itself, people tended to presume she had meant to kill the baby and required her to prove the child had been born dead or died naturally (pp. 3-4, 31-32). Many of McDonagh's chosen texts reveal individual adult violence and anguish, and group scapegoating and cruel indifference. We also see that state laws and customs presented as enlightened, and enforced by regimes of regulation and surveillance, create the barbarism they are said to exclude. (p. 144). Nonetheless, McDonagh focuses on the cultural norms a particular site exposes. It does not matter if an epidemic of infanticide occurred or was a phantom of public opinion(p. 126); the issues brought up in her texts, how childbirth was interpreted in a particular cause célèbre (p. 189) are (to paraphrase Orwell) the things she keeps her eye on. Three examples: in the 1857 Indian uprising infanticide comes to operate as a generalised sign of Indian degeneracy for the British (p. 138); for evolutionary scientists, infanticide, especially of females sustained close and complex relations with the institution of marriage (p. 161); eugenicists and polemicists for contraception suggest atavistic child murder will be stamped out if their agendas are followed (pp. 170-74, 178).

Nonetheless, what really happened also matters. It is possible to reach some accuracy even in records of deliberately obscured and subjectively-perceived multiple events. From a thorough study of many pre-trial depositions during the 200-year period in which McDonagh's source texts were produced (New Born Child Murder: Women, illegitimacy and the courts in eighteenth-century England, 1996), Hugh Jackson demonstrates that in fact changes in British statutes did not protect children or lead to more humanitarian behavior to women, but enabled British courts to prosecute an unmarried woman whose new-born child had died on separated charges of concealment and manslaughter, with the result that more women were punished by prison sentences and transportation. From a careful sociological study of violent women (When She was Bad, Penguin, 1997, pp. 64-91), Patricia Pearson demonstrates that a new-born child is as much at risk from its mother as anyone else; the present presumption today against a hired caretaker is unjust. Real behavior in local communities towards a given women's control over her body affects the consequences of a child's death for the mother too. As McDonagh has shown (in an article she wrote analyzing the 1994 Caroline Beale trial for infanticide1), an unmarried woman will still find herself under suspicion for new-born child murder in the US or UK if she is publicly seen to have concealed her pregnant body or parturition.

While she shows concern for abused individual women, in her book McDonagh seems more strongly to express a concern that strongly progressive narratives of child murder, or those which justify it, dominated in the 18th century (p. 195) and eugenicists and philosophers alike were willing to countenance child murder in some form. Thus, were it written in a more popular style, her book could be fodder for the anti-abortion agenda in the US and UK .

Craciun's book reveals how staying with accounts that may be literally bogus endangers the vulnerable. Craciun's marginalized and defamed women are three Marys, Lamb, Robinson, and Wollstonecraft; Marie Antoinette and Charlotte Corday; Charlotte Dacre, Anne Bannerman, and Letitia Landon. She interweaves discussions of their work with discussions of the work of women who are today becoming part of a re-imagined wider literary canon (e.g., Helena Maria Williams, Anne Grant, and Felicia Hemans); of male romantic and gothic writers (most notably Matthew Lewis, Scott, and Byron); and with arguments drawn from modern deconstructionist and feminist studies of l'ecriture feminine in poetry and gothic texts (e.g., Margaret Homans's Bearing the Word, Luce Irigaray's This Sex Which Is Not One, Eugenia DeLamotte's Perils of the Night, 1990). Craciun objects to the censured way that liberal feminism has depicted monstrous women, bacchantes, maenads, and femme fatale motifs found in women's writing. Against her bete noire, the female dream of love and independence outside power and history found in Jane Eyre, and the elusive autonomous female subject that erupts in rebellious rage against the repressive constraints of male power (as studied in Gilbert and Gubar's The Madwoman in the Attic), Craciun shows women's undeniable participation in a symbolic and political order . . . grounded in violence (pp. 23, 27).

Each chapter represents a different phase of Craciuns argument that many women have an urge to be violent and destructive, and not just in self-defense or revenge, but without provocation and towards female objects. Many enjoy imprudent play and arbitrary and irresponsible uses of power, and writing and reading about femmes fatales and vatic siren-like sybils. Craciun confutes cliched assumptions about innate or culturally-induced femininity, e.g., women's imagined tendency to idealiz[e] the mother/daughter bond (p. 212); to identify with and justify self-sacrifice; and to exalt poverty, sickness, pain, self-abnegation, and punishment (e.g., pp. 231-33). Craciun reinterprets Dacre's, Bannermann's and Landon's depictions of femmes fatales. Dacre's passion-ridden, part-lesbian and murderous Sadeian (Juliette-like) heroines utterly subvert the definitions of woman authors that we imagine Romantic-period authors relied upon (pp. 137, 141-42, 154). Bannerman's poems are oracular curses which need their veiled terrorizing nihilistic females to make their effects (pp. 163, 169, 171). Landon recreates the Byronic Melusine archetype from a woman's point of view (pp. 209-15). In Landon Craciun reveals to the reader a non-sentimental urbanite who wrote witty prose satire (pp. 204-9) and a novel (Ethel Churchill, 1837) where Landon identifies with an ambitious, adulterous, ruthless heroine for whom Landon wrote some of her most moving fragments of verse (pp. 230-31). Craciun's goals are to make us remember the crippling circumstances these women had to negotiate and their courage, to lead us to understand them, to include them in the new canon, and to enjoy their texts.

Craciun renders a significant service to the literary study of women's writing by showing we need not decide between alternative gender-complementary models of Romanticism (p. 22). However, Craciun's praise for some aspects of her texts require an illusion of self-control or mastery and power. In The Sadeian Woman, Carter writes that one of Sade's cruellest lessons is that tyranny is implicit in all privilege. A liberation from the limitations of femininity may be gratifying, may extract vengeance for the humiliations women have been forced to endure as passive objects, but if it is a liberation without enlightenment, it becomes an instrument for the oppression of others (Penguin, 1979, pp. 27, 89). Craciun herself suggests that the jarring violence of Mary Lamb's poetry mirrors what happened to Lamb when she was imprisoned in asylums (pp. 34-38); she focuses on how the anathematizing and calumnious way Marie Antoinette was represented in her era led to her harrowing trial and murder; and she describes how Landon endured childbirth three times in stealthily hidden ways and later committed suicide (pp. 78-81, 197-98, 212). Craciun writes much about the centrality of our bodies (and disease) to our experiences and clearly means to influence the way we think and how we shall live. She would see a change in the configuration of sexuality. But when she says that Nietzsche's question, Would a woman be able to enthrall us if we did not consider it quite possible that under certain circumstances she could wield a dagger against us? reveals the connection between the violent woman and the femme fatale, the unfemale and the hyperfeminine, that is central to this study (p. 15), she does not distinguish the securely powerful from people without power to control what is happening to them. She demands that our culture recognize and appears to celebrate such aggression and agency in opaque language that neglects accountability.

Julia Kristeva has argued that civilized society often fails to recognize the uncivilized Other as part of itself (Powers of Horror: An Essay in Abjection, 1982 Columbia, pp. 53-5, 70-9).2 Like Kristeva, McDonagh and Craciun draw attention to the "barbaric on a huge scale," and abject, destructive and willful terror, despair and desire in individuals. I began this review with Hill's imagined demon-mother rather than modern variants on Medea (e.g., Christa Wolf's Medea, 1996) or real recent cases, like Amy Ellwood's murder of her newborn infant (Long Island, 1988) and the serial killings of Aileen Wuornos because Hill's embodiment continues to attract a large audience. The smaller audience for McDonagh's and Craciun's books will be able to see the field of literary and women's studies differently, and notice things they had not before and in new ways, things that may enable all of us better to understand why stories of violent and abused women and dead children continue to be turned into fearful myths as well as the hidden, erased and fraught material that is part of historical and national identities. Perhaps too these books may also help us to make us recognize what we are and do -- the uncivilized 'Others' we make of others, and who exist in ourselves.

George Mason University

ELLEN MOODY

2 Quoted by Val Scullion, "Susan Hill's The Woman in Black: Gothic Horror for the 1980s," Women: a cultural review, 14:3 (2003):302-3.