Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

In defense of Edmund Bertram; Two ends of a spectrum: Vampire Harlequin Janes (& Twilight books) versus Agnes Grey & Mary Reilly · 20 February 09

Dear Friends,

A few days ago Laura, an editor of the online magazine for the Jane Austen Center in Bath, contacted me to say she was putting another of my early postings to Austen-l on the magazine’s site. It’s called “In defense of Edmund Bertram”.

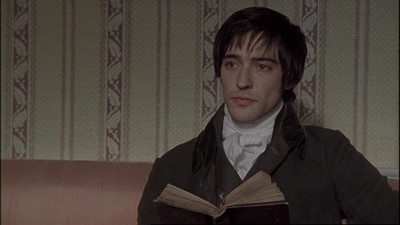

Blake Ritson as Edmund (2007 MP) falling in love with

Bille Piper as Fanny Price

I would not change my line of argument: “he is good, kind, decent, absolutely loyal, unwilling to wound, sensible. This too is, I think, true of all Austen’s heroes once we get to know them.” I would, though, qualify & contextualize. I do not write about characters in this simple way anymore—I take into account how they are in the novel’s art.

More’s the pity :). There is a clarity, grace, and accessibility in this early posting, which I fear (like other people who are academics or semi-academics) I have lost. As to content, my guess is had I still been able to write a proposal on the ethics of a character placed against our real world today instead of “Disquieting Patterns in Austen’s fiction”, my proposal would have been accepted for the next JASNA, October 2009, Philly.

Then late yesterday on WWTTA my friend, the writer, Diana Birchall, brought up the topic of “The Toothless Teen Vampire Genre.” She had earlier that day asked me if I had any thoughts which could explain the sudden popularity of these trash sequels, e.g., Pride & Predator and Jane Austen among Zombies.

I said no, but replied further by asking her if she noticed the frequency with which the name “Poppy” shows up. For example the heroine of

To which she wrote:

“Sure seems to, Ellen. I’ve just read a vampire novel with a Poppy as heroine. I’ve got to be unspecific here as I can’t talk about my work, but suffice it to say I’ve had to read a lot of teenage vampire novels lately. It seems to be an unstoppable genre, of unending fascination to young women particularly, and I’m baffled as to why. It would have had no appeal to me at all as a teenager. The teen vampire novels I’ve read are mostly very anodyne – toothless vampires, you might say. They usually drink blood, but in a nice way, if such a thing is possible. There’s nothing gruesome or gory about these books, and they have no graphic sex. Just dreamy young girl romance, and fantasy adventure. They’re not gay metaphors either. The dishy boy is a nice eligible vampire, that’s all, and he and the spunky girl save the world.

My eleven-year-old cousin, a very bright and sophisticated little New York girl, devours tons of these books. I don’t get the appeal.”

By the following morning I thought of this explanation:

It seems to me these books belong to the Harlequin kind. Deborah Kaplan argued a while back that the film adaptations represent a Harlequinization of Austen’s novels. I’m not sure I agree with that, but I can see why someone could argue it. The key thing about them is they are non-violent and make the vampire into a basically harmless suitor mindful of the welfare of the heroine. Pride and Prejudice and the Zombies; Pride and Prejudice and the Predator. The use of this specific title shows the desire to reach the huge audience which has been told this novel is the greatest thing ever written outside Shakespeare (the sort of comparison one hears): literally 200 and more % of people have heard or or read P&P over all her other novels. Lost in Austen was a P&P film sequel. P&P film adaptations & sequels way outnumber the other ones.

When I taught gothic a few years ago, I ordered a volume of vampire tales. Alan Ryan, Alan, ed. The Penguin Book of Vampire Tales Penguin, 1987. ISBN 0-14-012445-4. Well these are not vapid and anondyne: they were brutal, and more than half frighteningly misogynistic. The vampires kill women and go after them with the same ferocity we see in Bram Stoker’s tale: men drive stakes into women (the phallic symbolism is obvious), drain their blood, humiliate them. It was then I learned that the vampire tale is a often horror fiction which differs from the other subgenres precisely because it’s much more often written by men and filled with hatred and fear of women and slides into porn.

The comparison with say Cox, Michael and R. A. Gilbert, ed., introd. The Oxford Book of Ghost Stories Oxford, 1989. ISBN 0-19-282666-2 is striking & instructive. Not brutal, often written by women (maybe more often), with sympathetic heroines (like Mary Reilly) and pro-women, and heroes who are sensitive (nervous, like a Le Fanu or Oliphant hero) or very perceptive—like M.R.James and Edith Wharton’s and Henry James’s ghost stories.

John Grimshaw (1863-93), Trees with Shadows on the Walls, Rounday Hay Park, Leeds (1872)

By contrast, now we have this new weak, non-violent, gentle kind of vampire story for women with characters called Poppy. Well how about this for speculation: all this overt worship of power, freedom (supposedly) to have sex (which favors men as it makes women available to them in a culture where men have enormous power and far more money) produces a male genre which is emasculated so as to not to frighten or hurt the female reader who really does not want to engage with anything serious. There are silly male books, like say Wilkie Collins’s mystery-detectives and action adventure stories, mysteries, science fiction so when I use silly I don’t mean to pick on women as George Eliot did, hating herself for being a woman in the famous critical essay so often reprinted.

Julia Roberts as Mary Reilly reading one of Jekyll’s books (from the 1996 film)

Suzy McKee Charnas—remember her Vampire Tapestry writes an intelligent feminization of a vampire story in the 1980s, and I have a book from another once widely sold series, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, where again the vampire is really a brutal creature—Yarbro presents women as masochistic. Valerie Martin’s Mary Reilly actually combines the brutality of the vampire-werewolf tale with the feminism of the ghost terror story of a Radcliffe. Martin’s remarkable short story “Sea Lovers” (originally titled “Spawning” and in The Consolation of Nature) has brutal mermaid who casually murders a fisherman (reverse of old folk tale).

So what we have are Harlequins with vampires, zombies and supernatural terrors hitherto part of genuine taboo-breaking horror stories. The silly Twlight books selling wildly fit right here: inane Harlequinea, giving the girl a titillation of vampirism, but because she really is not masochistic and into violence, turning back to giving her a hero who will mother her (see Juhasz’s book on Reading from Heart on heroes as kindly mother substitutes). The word “Jane” in the title and suppose connection to Austen is the “clue” or sign that we are in popular harlequin land. We are really with cosy Jane still, only this time there are apparent vampires at the table drinking tea too.

Yvette suggests the idea is to laugh at the incongruity with disrupted Austen characters as they appear for example in Hugh Thomson illustrations. What an incongruous mix. It’s trivializing very much in the spirit of the most recent free adaptation of P&P, Lost in Austen. The mini-series begins with with a resonant reference to the anonymity and stress of modern life and the desire of the heroine to escape nightly by reading P&P. In the first two parts of the movie, there are thoughtful allusions to previous Austen movies, but as the changes in the story mount up, they become incoherent and silly, and by the end the series is filled with inconsistent absurdities, neither fantasy or realism. The ending undercut the serious charge of the opening by being in effect nonsense.

As a contrast: Yvette and I have been listening to Anne Bronte’s Agnes Grey read aloud beautifully by Donada Peters: this story of a repressed governess has more genuine passionate emotion, brutality, vampirism (draining the life out of someone), more raw life (the young woman attempts to build a life for herself by succeeding in jobs where she is subject to an all-too-usual cruel humanity) than any of these thin vampires.

Anonymous photograph of unidentified woman servant, London, 1890s

Ellen

P.S. Jenny Turner suggests that we should imagine what

Buffy the Vampire Slayer mocked in passing as too

stupid to even waste feelings of dismay about if

you consider someone could enter into such feeble

conventional dreams, is taken seriously here.

There are website of Twilight Moms: the sort of

thing where people raise their hands to be

counted as stubbornly and taking pride in,

showing off about their disappointment and shame (hiding in plain sight?).

She is one of those designated to write about

women’s books (LRB is one of those periodicals

where there are 8-9 articles by and about men’s

books to every 1 by and about women).

http://www.lrb.co.uk/v31/n06/turn03_.html: Jenny Turner, the LRB 26 March 2009.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Joan on “In Defense …”

“Congratulations Ellen. It’s a beautiful layout and very interesting article, Joan”

— Elinor Feb 20, 11:06pm # - On the Everyman Agnes Grey: First Anne Smith’s introduction is good. She succeeds in rescuing Anne from the stereotyped picture of a dull conventional woman her sisters inadvertently created. She shows how the evidence suggests a very kind of person than her sisters: for example, Anne went to a highly social house as a governess and was there for a considerable time. Her tone in her books is different, quite different. She is a realist, and she break taboos explicitly when she describes marriage, alcoholism. She died young and we cannot know much beyond what is left to us of the poetry and her two novels.

The book really doesn’t read like Jane Austen though—to whom Anne Smith like others compare’s Anne Bronte’s tone. It’s not satiric. It’s downright and plain. The story of how Agnes’s fatherloses all his money reminded me of Sexty Parker. Mr Grey, a curate, risks all his capital on speculative ventures and loses it. I had the same kind of hard time reading about Agnes’s first posting as I did watching Jacques Rivette’s La Religieuse. The plain truth of the awfulness of many children, the stupidity and cruelty of many people, Anne’s own high morality unable to reach anyone, her idealism and strong self-possession amid this abysmal continual vexed tyrannized over life is just so difficult to take. Partly because it’s so convincing. It’s the quietude of the tone that is so powerful and its candour combined with the same kind of rectitude that lies behind a fiction like Trollope’s.

And the experience is analogous to many today. As I read, I remembered my first social experiences as a teenager. What I saw growing up when I was in school. I could relate directly as I do not often to Trollope’s women.

In her second posting one she stays at for a few years, with the Murrays, and slowly a quiet love begins to emerge between her and a curate. I had wanted to compare her to a novelist I really feel she is like: Dorothy Richardson in Pilgrimage. In the first three novels of Pilgrimage, Richardson tells of her time at a girls’ school and a posting as a governess. There is abosolutely no false romancing in Richardson, something hard to pull off since Jane Eyre. I’d like to say this is true of Anne Bronte in the first posting, but that she veers off slightly for a quiet love story slowly emerging in this second part of the novel. It’s still not romance. I think we may be intended to look at her ironically in the manner of Richardson’s heroine: too rigid, too unbending, but that her rectitute is what we are supposed to measure her cruel and dense and bullying and stupid employers in the first posting and her worldly and cruel in a more ordinary way and ultimately stupid employers in the second. The book also reminds me of Harriet Martineau’s Deerbrook. I mentioned Martineau but she is not alienated from that social world; she is eager to work for betterment, to educate, hopeful. That’s not the case with Dorothy Richardson. Richardson is really the closest

Who is the book intended to please? Not upper class employers certainly. She speaks out to other women who have endured what she has endured; surely she doesn’t expect to improve the behavior of the employer class ;) She is also releasing her emotions.

I am struck by how all three Bronte sisters write of isolation so often, of people in the fringes. Also animals. Agnes is very kind to an intelligent poverty striken kindly poor widow, Nancy Brown’s cat, and to the family dog who everyone but her andt he curate, Mr Weston, is carelessly cruel to.

Gaskell’s My Lady Ludlow makes a good comparison. Both by women, both novellas, and interested in social conditions, but also a contrast: not only does Gaskell show a strong tendency to the idyllic in her novellas, and uses male narrators (first person as in My Cousin Phillis) or an unnamed presence who is detached (this crippled young maid in MLL) but when Gaskell shows reality, criticizes, it’s from a perspective of social circumstances. People are grieved, miserable, at a loss, in trouble because of economic arrangements—this is also true of her Mary Barton and North and South. For Anne Bronte, it’s their moral nature that is awful and a brute fact, not the result of deprivation or having enough or too much.

A severe ethical position whose tenets are difficult to say no too: like kindness, decency, courtesy, sincerity, and much more all of which are generally wanting in the people she meets outside her family, and Weston and Nancy Brown (I’m about 2/3s through)

Perhaps this implicit kind of half-satiric point of view – the satirist is a corrector—is why she’s connected to Austen as well as the quietude and diurnal nature of the fiction. I agree Trollope usually (not always, not in his short stories or some of the novellas) deals with people of a higher class than these employers, but not Austen. Films suggest people are making the milieu Austen describes higher and richer than it is. Only the Bertrams are thoroughly well-heeled and connected, and even they are in trouble, need slavery to carry on; the Elliots once were and are losing out. Darcy is not the central character; it’s the Bennets, who are very like in milieu those Agnes is employed by; also the Dashwoods. Knightley is well-to-do but works as a farmer and brother has a working profession he must return to.

I’ve dipped into Rural Rides. Cobbett is severe but the point of view is that of Gaskell: looking at social and economic arrangements, instead of as in Bronte saying human nature is the problem (so to speak).

Agnes Grey is not atypical in size, but let’s think: Trollope wrote 47 novels of which 13 are novellas, novels of just the length of Agnes Grey and with a similarly lucid simple but passionately evocative style. Henry James’s oeuvre consists of about a 1/4 novellas: famous ones include Washington Square, Daisy Miller, The Awkward Age, The Europeans, and these are just those that immediately came into my mind. Thackeray’s works (14 volumes) show up a number of novels of this length; LeFanu, Gaskell, Wharton (a little later, Edwardian), Oliphant all wrote these. Not everyone wrote in the overwrought metaphoric style of Dickens.

The thing is to make money and be distributed you had to please Mudie’s and its competitors and that meant a BIG book, 3 volumes for the marketplace worked on this size book; the customer rented one volume at a time and paid that way. Once the stranglehold of this system was broken, the 3 volume novel disappeared pretty quickly and R.L.Stevenson’s most common size book was a novella.

Often these novelists first books are novellas: George Eliot’s Clerical Tales, Silas Marner come early, Henry James has many novellas, Dickens too (The Christmas Carol is but one).

For myself I think it’s the content that pulls us in Agnes Grey. The shadow or half-buried story of the Grey family, the father’s failure, the daughter’s self-abjection, but then coming out strongly, changing, growing, becoming independent and self-dependent, and that is the story that counts. She is not giving us a love story even if it ends that way; it’s a story of a woman learning to live on her own in the only and hard and harsh economic environment she is offered, the only job that’s respectable (barely), governess, servant in households. Now that is Anne Bronte’s story only she was cut off by death.

Surrounding her are these foolish frivolous half self-destructive people she must work for and they provide contrasts to what is decent and good and pleasant in life. The story of Hatfield’s courtship of Rosalie before she marries; her rejection of Hatfield sheerly on the basis of rank; Hatfield has with decent good feeling, her leading him along and then humiliating him is powerful because we are shown his anger, pettiness, and how she lies to him. He comes revengeful and startles and shocks Agnes—who is not Anne. There is an ironic distance between Anne and her heroine. Anne is not shocked or frightened by Hatfield. For the first thing Rosalie does is tell others. Anne Bronte is showing us how hatred arises in life and why things are so ugly, and yet the man at least had good impulses in him. They were played with, abused, mocked and then electrified by humiliation. The making of nastiness and cruelty in others is shown and Bronte does not see this as a result of economics but human nature interacting with others. Only the rare person does not turn into a sort of Hatfield or Rosalie.

Really this is far more insightful than Emily who is a savage mystic. Charlotte is a romancer in comparison, obsessively retellig her autobiography; she tried to break out of this in Shirley but did not manage for the central story is her and her sister, and the depiction of economic arrangement is very much secondary and muddled.

Agnes is the center of the book and it’s not about passionate romance in the way of Charlotte or Emily’s books but about a woman trying to exercise or prove and achieve independence and capabilities. Now in that it is atypical. But the story is muted; it’s there and is the basis of the plot-design; the story of Weston does not emerge until Agnes Grey is 2/3s over. As in life the man the woman marries is not the central aim of her existence for real, and her existence goes on afterwards. She is a person in her own right struggling to become.

And there is much poetry in the language and poetry she wrote alongside the book—as shown by Smith in the later part of this edition.

Ellen

— Elinor Feb 21, 7:36am # - From Diane Reynolds:

“Ellen,

This is an interesting message.

I just finished reading Twilight, (“the NYTimes number 1 bestseller”), about a teenage girl’s romance with a vampire, and it was, to a large extent,Harlequin meets kindly (but inherently dangerous!) vampires. However, the pairing of Jane Austen and the vampire genre that you discuss, if Twilight is a representative work of the genre, completely upends what Jane Austen is all about.

What struck me particularly about Twilight (and I’m writing a piece on this) is the extent to which the teenage girl heroine, Bella, who begins as free and independent—is infantilized by her encounters with vampire world. A parallel could be made to Twilight and say, P&P, in that both books on some level (Jane in a much more sophisticated way) start from a premise of inadequate parenting. However, while the trajectory of an Austen protagonist is towards maturity and as “whole” an adulthood as the patriarchal culture afforded (and the critique Jane makes when it seems evident a woman will not become fully whole is of the culture,not the protagonist) , the trajectory of Twilight was toward the increasing helplessness and hence dependency of the protagonist on a protecting, parental male who runs her life for her.

So, in other words, what is arguably most attractive about a novel like P&P—the growing maturity of the heroine and her possibility of achieving wholeness in her relationship with a male equal—is completely undermined by vampire genre (assuming Twilight to be typical). I don’t know if even Jane would appreciate the irony, but I’m sure she’d understand it.”

— Elinor Feb 21, 7:56am # - From Elissa on Janeites:

"Thank you Ellen for that interesting perspective of vampirism and the heroine in contemp novels/filmic treatments [I’ll happily skip these]. The subject had much play in American literature and American “theo-philosophical” thought and writing from the 1830s throughout the 19th century, especially involving transcendentalism, utopianism, even Swedenborgianism and other “spiritualist” movements. Emerson and William James took it seriously; Twain vamped and made enormous fun of it all; Henry James “Freudianized” it.

Psychological, or spiritual, vampirism is a major theme running throughout the many, many tales of Nathaniel Hawthorne as well as his novels The Scarlet Letter, House of Seven Gables, The Blithedale Romance, and The Marble Faun. If Ahab’s haunting by [or is it the reverse?] of the White Whale isn’t spiritual vampirism on a vast, oceanic level, at least it conveys the spirit with which its author Melville attempted to swallow his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne up alive [Hawthorne and his wife actually had to flee the Massachusetts countryside to get away from Melville. They did so with the assistance of Hawthorne’s old college roommate, President Franklin Pierce].

But it is in the novels of Henry James that this theme of psychological vampirism comes to full fruitition. It appears in so many of the Tales that I leave the delightful discovery to the reader. But in the novellas and novels, we may look especially to The Spoils of Poynton, The Aspern Papers, The Sacred Fount, The Europeans, The Bostonians, The Portrait of a Lady, The Tragic Muse, The Wings of the Dove, and The Golden Bowl. In The Sacred Fount and Portrait, traditional “vampire” language and the very real sense of sexual energy that revitalizes one from preying on another is actually used and woven into the books’ metaphors.

Elissa

— Elinor Feb 21, 8:02am # - What an insightful comment in reply, Diane. I’ve noticed the recent spate of Austen movies (the three film adaptations, Becoming Jane and Miss Austen Regrets), all show us the heroines in states of abjection; in the case of Persuasion, Wentworth is in a similar kind of distressed mood, but Anne Elliot is nearly unable to function as she nightly weeps hysterically into her diary. She allows herself to be blindfolded in the last scene: he will lead the way utterly, provide for her.

What a return to retreat, helpless too. The opposite of what is found in Agnes Grey.

Diana used to tell me she was thinking of a Byronic fiction sequel, which might include gothic elements. But I suspect this kind of thing we see in Twilight is sheerly inane—rather like the hodge-podge of the last parts of Lost in Austen, also about retreat.

What we are stressing, Elissa, is how silly these books are in comparison to real gothics. I recommend Mary Reilly sometime by the way :), and Martin’s The Great Divorce, “Sea Lovers” in Consolation of Nature (about a brutal mermaid) and Property.

Ellen

— Elinor Feb 21, 8:03am # - Hi Ellen

I read your comments on the vampire genre this morning and found them fascinating. With an 11-year-old daughter and an entire class of CCD students obsessed with Twilight I obviously have a direct interest in this genre.

I posted a Tweet about your comments but didn’t have a url to link fellow Tweeters to. Are you familiar with Twitter? Anyway, if you have developed this idea somewhere on the internet that’s accessible to the public I’d love to know.

I think it would make a great article too, by the way.

All the best,

Erika Kotite

— Elinor Feb 21, 10:01am # - From Jill:

“Dear Ellen,

I forgot to tell you that I read Oliphant’s Beleaguered City, with her other ghost short stories, while I was gone. I also read Mary Reilly. Beleaguered City was by far the best. Mary Reilly was wonderful too; I’m eager to get to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. MR was that good a book, I wondered what happened to poor Mary after it was over.

Vampire stories never have apealed to me; I don’t understand the long-held attraction of so many for them.

It’s funny how these books (Agnes Grey, Beleaguered City) have never been odd to my way of thinking.”

— Elinor Feb 21, 1:55pm # - An intelligent assessment of the prods and cons of the Twilight series by my good friend, Kathy:

“I read with interest your thoughts on the vampire books (paranormal romances). I have read the first three of the Twilight books, recommended by a teacher friend who often reads children’s and adolescent lit. I admit I enjoyed them. They’re Perils of Pauline books. The first is well-written in a galloping action-adventure way, but the heroine is extremely, traditionally passive, a lovely girl constantly being rescued by her vampire boyfriend. The next three are fast but clumsily written: I have a feeling Meyer wrote them quickly as the first one was such a success. Oh, by the way, some read these as “safe sex” books: the vampire refuses to have sex with the heroine until they’re married (fourth book). And that I had to stop reading because it’s obviously an anti-abortion book: the heroine gets pregnant with a vampirical fetus who kicks and breaks her ribs and yet she refuses to abort (even the vampires want her to). These are definitely post-feminist books.

I haven’t read the others – I have a feeling the Twilights may have been the first and best – but there are a lot of paranormals around lately for adults and kids. There is a very good adolescent series about “faeries” by Holly Black, in which a tough girl discovers she is a changeling and has to deal with a terrifying sub-cemetary world of “faeries,” among whom is a moody, chivalrous man, her love interest (many of the faeries are much more frightening than the vampires in Twilight). In fact these faerie books, Tithe and Ironside, and one other whose name I’ve forgotten, are horror books rather than fantasies. But I prefer them to Twilight: better writing and more interesting concepts. , And the heroine can take care of herself. In the third book (the one whose title I've forgotten) there are other issues than fantasy: the protagonist catches her mother having sex with her boyfriend and in grief and anger disappears into the subway system of NY, living with a group of teenage drug dealers who deliver “Never,” a heroin-like drug, to faeries. That one was fairly gross and tough, but the heroine learns fencing from an ogre, solves a murder, etc., etc.. Anyway all three of these books are appropriate for adults: they simply have adolescent heroines so the books can be marketed to a specific audience.

Well, that’s my quota of adolescent books for the year. But some of them are well-written, actually much better written than the adult sci-fi and fantasy out there.

Here’s a link to an amusing Twilight blog:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/global/booksblog/2009/jan/08/twilight-vampire

Kathy"

A greal deal about the conservative utterly unfeminist agenda of the books is explained by Stephanie Meyers's background as Mormon. E.M.

— Elinor Feb 21, 10:09pm # - From Teresa on Austen-l:

“Ellen,I read the four volumes of the Twilight series, in a few weeks, after seeing the film with my 20 year old daughter. My curiosity got the be

st of me. Fascinating stuff. Not great writing but page turners none the less. And in the last book some “Rosemary’s Baby” type scenes that seemed quite freaky to me. The main character’s name of Edward was inspired by Jane Austen’s heroes so says Stephenie Meyer. A HUGE commercial success and I think sad to think that so many teen girls are so inspired by these books. I do think there is a lot of Mormon doctrine in them. Like marriage for eternity. There is something very odd and psychological about them. I’d be interested in knowing what others thought. To be fair, Stephenie Meyer wrote the first bookfor herself, and then was encouraged by her sister to get it published; the books have made her and her publishers a small fortune, I’m sure.”

— Elinor Feb 22, 7:11am # - Teresa, I’m sure you may know about how books are marketed and the crucial importance of advertising and distribution networks. The Mormons did it. The books are ferociously anti-abortion; the vampire male wouldn’t think of having sex before marriage and if one does, no matter what (in one of the volumes a girl’s life will be directly threatened), one must have the baby.

The use of popular surfaces for a specific kind of Christian message has been going on for about 30 years now. Rock-n-roll songs whose lyrics are of these evangelical kinds. Highly contradictory but they bring in teenagers. The adaptation of P&P by a Mormon group was just such a movie.

The thing is to know what propaganda is being fed you and who is doing it. And after all the Net shows us this here.

Ellen

— Elinor Feb 22, 7:15am # - The Edmund Bertram piece looks lovely and is a good read – I do agree that he tends to be dismissed, as with Fanny, and it is good to look at these quiet characters in more depth.

I can’t really add anything on the ‘Twilight’/vampire books as I haven’t read them or heard very much about them, though of course I did know that they are very popular and there has been a film – doesn’t sound as if I’ve missed much! Just to add that there are also some boys’ vampire books, the Darren Shan series about a “half-vampire” who is trying to resist his craving for blood – my son Max and I read a couple of these together when he was a few years younger, but then he got fed up with them. I don’t think the half-vampire hero actually drank any blood in the books we read – they were really more about a young boy being separated from his family and struggling to make his own way in a sort of shadowy fantasy world.

— Judy Feb 22, 7:42am # - From WWTTA, a member sent along the following URL to the Martha Quest books by Lessing as an intelligent, passionate healthy engagement with life for teenage girls:

http://www.harpercollins.com/author/authorExtra.aspx?

isbn13=9780060959692&displayType=readingGuide

Worlds, universes away from this new superbestselling spate of anodyne vampire janes and twilight books. They are part of the new kind of literature for the past 30 years which takes modern seeming surfaces that sell and contradictorily make them project evangelical repressive religion and "patriotic" Americanism. There's a mormon adaptation of Austen's P&P and it's not all that bad, not all that much different for real than Clueless when you confess the truths about Clueless to yourself.

E.M.

— Elinor Feb 22, 7:48am # - From Fran:

"I’ve just been talking about the question with my younger son, who is much more up-to-date on the material, and he compared the genre’s popularity with that of gay or gay-seeming teens boys bands la Tokyo Hotel with young girls: the thrill and the flirt with none of the over-threatening sexual aggression…. I also posted it to a Feminist Sci Fi & Fantasy genre list, where it started it a good  thread. Many saw it simply as part of the perennial interest in transgressive vampire lore, adapted  to teen concerns and in this case especially fuelled by the success of such stories as Twilight

and its imitators.

However, there were a couple of more differentiated comments which I asked permission to pass on here as food for thought. I’ll put them in a separate email.My son’s given me a couple of things to watch from his collection, so I’ll be interested to see how they come across when compared with the earlier Buffy and Angel episodes I sometimes used to watch with the boys.

I was also very interested to read a comment on Ellen’s blog on the subject, which compared the heroine of the teen vampire series with Austen heroines and saw the modern teen shifting from comparative freedom and independence to progressive infantilism and dependence on a patriarchal protector whereas Austen’s protagonists advance to maturity and as much independence as the society of the time would allow. Not exactly a sign of progress today,

Fran

— Elinor Feb 23, 9:24am # - From the owner of the genre list:

“What it (toothless vampire) means, I think, is that many of these modern vampires are angst-ridden victims of the modern world, their formerly violentgnashings of teeth and tearing out of throats replaced by “pinpricks,” the favourite description of Feehan’s lovebites, even the evidence of the bite magically “healed” by the miraculous saliva of the Carpathians, whose real skills are in healing with secret herbs and the mineralcontent of the soil of their mountain homeland.

Then a longer comment, exploring the attractions of various popular genres and naming some titles

for consideration:

Vampires are traditional sexual predators in the old literature, asPirates, Moors, and “Wild Indians” were stereotypical bloodthirstyvillains and rapists. Modern Women’s literature (and most modern vampire stories are women’sgenre fiction) has a tendency to transform or “tame” formerlyfrightening or monstrous threats and remake them as useful members ofsociety, an elaboration of the “all he needs is the love of a good womanand a home-cooked meal” theory of male behaviour. So, in Christine Feehan’s enormously popular “Dark” series,he “vampires” are noble protectors of humanity with a fatal flaw, unlessthey find their “lifemate,” a human woman with psychic powers, they are doomed to descend into madness and depravity, helpless (but violent) babies without the moderating influence of their wives, so bachelors are driven to marry, eternally faithful, and always available to take out the garbage and squash spiders. Gilbert and Sullivan did much the same in The Pirates of Penzance, soone can hardly argue that women invented this “turnabout,” but it’s astaple of women’s genre fiction.

Genre fiction appeals to certain impulses in us all. Mysteries (although enormously popular among women) titillate our humandesire to see justice done, and to make us think that we, like the detective, literary agent, chef, or gardener in the story, are cleverand capable of solving problems. Men’s genre fiction tends to involve physical contests in which the heroovercomes physical obstacles in addition to any other needed task, andreflects (I think) no special desire of men to engage in barroom brawlsor gunfights, but rather to put these nightmares in their place asthings which can be solved through a physical prowess the reader mightonly imagine, but which rehearses a behaviour which seems desirable ifone has the bad luck to get into such a situation.

Women’s fiction, on the other hand,

rarely involves physical contests in which strength decides the outcome, although there are femaleaction heroines. These tend to be aimed toward a male audience, however,like Lara Croft, Tomb Raider, and the like, and are usually almostlaughably simplistic, women only in gender, men in drag.

What they do involve are complex relationship problems, and the pluckyheroines therein face daunting examples of difficult emotional or socialinteractions but none-the-less prevail and achieve socially-acceptableoutcomes, from Rebecca rescuing the bitter and moody Maxim, nearlysuicidal or insane from nursing a dark secret, or Jane Eyre’s Rochester, rescued in his turn by a woman (several times), during thecourse of which the protagonist undergoes her own transformation, fromgirl to woman and quite often wife.

In this context, the vampire plays the traditional “bad boy,” aconflicted and perhaps tragic Byronic hero, who is both succored andtamed by the woman, domesticated and brought into appropriate relationships with a larger society whose lineaments may be fantastic, but recognisably domestic.

The appearance of teen vampire stories isn’t exactly new, but they are proliferating just as adult vampires stories are. Where there were oncea handful of such stories, there are now hundreds of titles in print atany given time. Young girls want the sorts of titles their mothers read,but appealing to their own age group and interests.

I commend to your attention, in no particular order: The Television vampire “Soap Opera,” Dark Shadows, perhaps the first tofully exploit the “misunderstood” vampire who longs for true love. Suzy McKee Charnas, The Vampire Tapestry, Jody Scott – I, Vampire; Nancy A. Collins’ Sonja Blue series; Nancy Baker – A Terrible Beauty; Trisha Baker – The Crimsom Kiss; Meredith Ann Pierce’s Darkangel trilogy; Amelia Atwater-Rhodes – In the Forests of the Night; a part of the Den of Shadows series (young

dult)Cecilia Tan’s erotic vampire seriesCharlaine Harris’ Southern Vampire seriesJennifer Rardin’s Jaz Parks series; Elaine Bergstrom – Austra Family seriesLaurell K. Hamilton’s Anita Blake, Vampire Hunter seriesMary Janice Davidson’s vampire series; Lynsay Sands’ Argeneau series Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s Saint-Germaine vampire stories; Anne Rice’s Vampire Lestat series; Nancy Gideon’s Midnight romance series; Sherrilyn Kenyon’s Night seriesChristine Feehan’s Dark seriesRosemarie E. Bishop’s Moral Vampire series.Melissa De la Cruz’s Blue Blood series (young adult); Rachel Caine’s Morganville vampire series (young adult); Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series (young adult); Ellen Schreiber’s Vampire Kisses series (young adult); Kimberly Pauley’s Sucks to be Me (young adult); Anette Curtis Clause’s The Silver Kiss (young adult).

A nNote that some of these are perfectly ghastly, many don’t illustrate my general thesis, and the quality of some series, especially, is either uneven to

too even and repetitive. I’ve made no attempt to exhaust thegenre, or even my own shelves, but just took examples that struck my fancy for one reason or another.”

— Elinor Feb 23, 9:48am # - I enjoyed reading the article you posted on the Twilight books, Ellen,especially the ironic, implied element of unholy addiction to what are apparently objectively mediocre books. I came across quite an amusing Twilight fan site today, which called the series ‘a textually transmitted disease’. Nice one:) Must have been posted by a ‘Twilighter’ rather than a ‘Twiharder’, though. These fan groups seem to have a whole jargon of their own.

Fran”

— Elinor Feb 23, 9:50am # - The genre list owner’s posting is most instructive.

Myself I differentiate horror from terror gothic generally by noting that horror does tend to be bodily assault and break bodily tabooes, is often written by men. Of course there are exceptions. And terror fiction which includes ghost stories are more often written by women, threaten the central figure psychologically (no less devastating in its way). It’s a distinction that can be elaborated into male gothics (Matthew Lewis’s Monk is the progenitor or first or early one) and female gothics (the first full blown is really Ann Radcliffe’s Romance of the Forest; the first her Sicilian Romance).

I know there are mixes and would say Valerie Martin’s Mary Reilly is a successful mix with a female development and terrorized (but not, note NOT, bodily harmed in any way from Jekyll/Hyde) woman at the center; we are told of horrific brutality committed outside what she sees, to the level of a psychopathic werewolf paradigm. Mary is also really frighteningly abused by her father and her melancholy personality is partly a result of her early childhood experience of male violence.

The exceptions do not hurt what you learn by genuinely seeing the patterns and how they function.

Ellen

— Elinor Feb 23, 9:56am # - Someone dissenting:

“Meyers didn’t get taken up because she’s a Mormon. If she did, what about all the other utterly identical series? You’ve no idea how many there are! The House of Night, Nightworld, etc., etc. They’re very smoothly easily pulpily written to appeal to teens. These things sell like hell, in the millions. That’s because young people find them compulsively readable. They weren’t forced deals for a political anti-feminist agenda. It’s the formula itself that’s crazy popular. The readers drive that market. They can’t get enough of this stuff. Sadly young girls like fantasies about being ravished slaves of vampires. Of course dozens of series arise to cater to this taste, for one reason and one reason alone – it makes fortunes.”

— Elinor Feb 23, 10:17pm # - Quite right about my not knowing anything for real about what’s popular. I don’t. Tonight I began Wm McCarthy’s huge book on Anna Barbauld. I’ve been asked to review it. What a pleasure. And I look forward to read a Broadview of her poetry and an edition of her prefaces to her edition of more than 30 novels in the 1830s. I regret I have to put down Francoise Chandernagor’s L’Allee du Roi. Nothing could be further from what’s widely popular in the US. Both are to me delight and joy—as is listening to Agnes Grey and stories of that heroine's pleasure reading the Bible to an old woman and her cat. I find it soothing and inspiriting.

E.M.

— Elinor Feb 23, 10:31pm # - From Fran:

“Thanks for this – it was both interesting to read and good on the eye.

There’s a real ‘Twilight’ craze on over here at the moment, even the very good, small and usually highly literary book shop I use in town had one whole window display devoted to the theme when I went to pick up my Celan poems and the Celan/Bachmann correspondence. Those I promptly carried away in a black bag with a bloodily dripping red heart and a link to the Bella and Edward website – not exactly inappropriate, as it happens:) The letters are even entitled ‘Herzzeit’ in German – ‘Heart-Time’ – a neologism taken from one of Celan’s poems.”

— Elinor Mar 3, 10:31am # - “I have a book from another once widely sold series, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, where, again, the vampire is really a brutal creature—Yarbro presents women as masochistic.”

If that is your summary of Chelsea Quinn Yarbro’s Saint Germaine books, you have not read them. The main character aka the vampire is generally the most humane and most caring character in the books. The brutal, sadistic, and masochistic folks are the human beings. I think of her Saint Germaine books as more historical novels than vampire books. The settings range from 1st c Rome to 14th c. Europe to 12th c. India to 6th c China to 17th c Peru. One of her strongest characters is vampire Octavia Clemens, born in 1st c. Rome and lived until the 17th c. and not a masochistic women…obviously a survivor!

— Laurie Mar 11, 10:42am # - Dear Laurie,

I certainly have read Yarbro: I’ve read all her Hotel Transylvania and half-way through A Mortal Glamor (that was quite enough). I also assigned and read with a class a short story taken from one of her novels, “Cabin.”

Your comment demonstrates my central point: you read reading about vampires who are emasculated, gentle, kindly loving beings. You should read Suzanna Juhasz’s Reading from the Heart: feminine romance gives the reader heroes who are substitutes mother figures.

There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that if the themes are adult, fruitful, healthy, not inane, which Yarbro’s are. I remember the hero is capable of mean brutality and cruelty (I point out to your word "generally" when you deny this), though of course not to the heroine who is in all three cases presented as loving to be dominated, enjoying various thrills of near-violence (just kept back). My students were embarrassed by the transparency of the heroine’s masochism. Your evidence of a strong women is based on a silly fantasy about not dying. This is very like science fiction where death is not a problem. Nothing to be afraid of if you don’t die.

And yes Radway in her Reading the Romance shows that her women readers repeatedly say they are reading their overt Harlequins for the history. The claim is absurd on the face of it as the history is often inaccurate, romanticized to an extreme (like 17th century romances like Clelia or 19th century operas), and is in any case a matter of the marginalized settings. The rationale helps sell the books as it obscures the motive for reading them and flatters the reader’s self-esteem.

Yarbro can write a decent sentence, and more or less coherent plot which serves up matter which (as one of the commenters said) in disguise works out real life’s troubles in a way that comforts without asking the reader to think at all or make any conscious analogies with her own life.

Ellen

— Elinor Mar 13, 6:33am #

commenting closed for this article