Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Ruby in Paradise: A young lady's entrance into the world, another Austen film! · 2 January 07

Dear Harriet,

Just as I thought I’d finished seeing all the available films closely connected to Miss Austen’s books, I discovered and watched a 17th, a very good one too: Ruby in Paradise, written and directed by Victor Nunez, a 1993 independently-made film, starring Ashley Judd as Ruby, Todd Field as Mike, Bentley Mitchum as Ricky, Allison Dean as Rochelle and Dorothy Lyman as Mrs Mildred Chambers.

Even if it had nothing to do with Austen, it’s a fine moving intelligent film in its own right. I believe it was nominated for (and perhaps won) some prestigious awards that year. For more details go to IMDB.

Ruby in Paradise connects to Jane Austen in precisely the way the 1990 Metropolitan and 1995 Clueless do. It’s a matter of transposition. The story is that of a young lady’s entrance into the world. The young lady is 20, named Ruby Lee Gissling (Ashley Judd), and first seen driving steadily in her car away from Tennessee now that her mother has died. She takes a turn in the road and chooses Florida (it’s said to be warm) and succeeds in selling herself aggressively (“I’m good at retail and I come cheap; I’ll work hard!”) and landing a job for Mrs Mildred Chamber (Dorothy Lyman) in a sort of junk-clothing-gadget-accessory store.

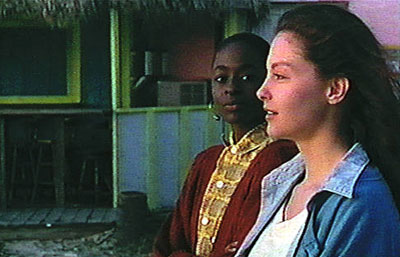

Ruby proceeds to make friends with (among others) another girl there, Rochelle (Allison Dean), black and herself going to business college. Ruby is not going to college because Ruby hasn’t the money.

Ashley Judd as Ruby, Allison Dean as Rochelle

With much less fanfare than Clueless this film is multicultural. Ruby’s boss is at first suspicious, watches her guardedly and and tells her that Mrs Chambers’s precious son, Ricky (Bentley Mitchum), is “off-limits” to employees. She’s not going to have an unscrupulous woman going after him (shades of Austen’s Fanny Dashwood).

Bentley Mitchum as Ricky Chambers

Ricky turns out to be a low-life sleaze, a coarse aggressive type (for those who’ve read Northanger Abbey, the analogy is John Thorpe) and he pushes himself onto Ruby while his mother is away. She is casual about sex and has a brief liaison with him. She sees him for the heartless exploiter he is, the phony (he gives her a present she discovers multiples of in his drawer), and goes out with him for a minimal while. As soon as Mrs Chambers returns, she manages to break the relationship off.

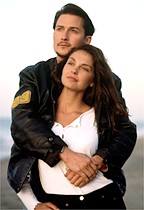

Ruby then slowly becomes involved with a much better type, Mike (Todd Field), a serious reader, environmentalist, works for good causes, and he falls in love with her. He’s an idealist and is trying to teach her (Henry Tilney):

Ashley Judd as Ruby, Todd Field as Mike

There are many books in Todd’s inexplicably beautifully-appointed flat, and one day he pulls down Northanger Abbey to give her to read. Ruby begins to read it aloud, and it sounds very strange in the environment (this is a signal to the reader about how foreign Austen feels at first), but Ruby finds herself keeping on and finishes it slowly. About 2/3s the way through the movie she’s reading the ending by the cash register when no one is looking. At punctuated points Mike discusses Austen: of NA he says it “saved my soul,” “restored peace to my heart” and “joy to my soul.” Later he talks of how Austen dissected society; how she seems to “dwell on the superficial” but the center of her books reveals the value system of her era and society, that no one is so lucid as she. The talk about Jane Austen is recalls the talk about her in Metropolitan (where the books explicitly alluded to are Mansfield Park and Persuasion) except that there’s nothing negative said. In Metropolitan we are told that Trilling said Austen’s MP was obsolete and dated and Fanny Price unlikeable. Ruby clearly doesn’t feel that way about Northanger Abbey. She is seen closing NA with a very happy look in her face.

Mike reminds me of Josh in Clueless, only unlike Cher (and Emma in Austen’s novel), Ruby does not quite fall in love with this ideal intellectual well-meaning, grave, serious hero, does not admire what she labels his “gloom and doom.” Rather she calls him a “snob” for his aspirations (so have recent readers of NA called Henry Tilney). She doesn’t like how Mike won’t sit through trash movies (she finds the climax really “exciting,” “the best part is coming!”), but will sit and listen to religious broadcasts on TV which he agrees are manipulative, hypocritical, sleazy. He says he needs meaning and it links back to tradition and his childhood. She says she’d like to forget all she knew in her childhood and how her mother was used until she died.

However, Ruby’s friendship with Rochelle continues and becomes more binding emotionally. They identify with one another, and we are to see that she’s learning as much as Rochelle even if Rochelle will be eligible for jobs Ruby won’t: Mrs Chambers at one point takes Ruby to a kind of conference and also to warehouse shopping and makes her an assistant manager. But the movie is not anti-college for another girl, Debra Ann (Betsy Douds) who rents a room in Ruby’s complex is beaten by her boyfriend and has a bad job, and no prospects because she never went further than high school and seems to not be competent in herself. She keeps saying how she’s learning so much.

Ricky manages to sabotage Ruby’s job: he tries to get her to go to sleep with him again, forces himself into her flat, tries rape, and when she throws him out, lies to his mother who we are given to believe fires her. Ruby then has to get another job, and goes from place to place unable to find one. We see her rejected in scene after sceen. She’s now having a hard time making her rent and buying food. She grows thin. She almost takes a job as a stripper and we are treated (so to speak) to watching how such women are treated publicly when they strip. Awful. We see how a girl must offer her body completely, let men see her vagina, and how money is slipped up her thigh to try to get her to sell herself later. Ruby turns away from this in the sort of repulsion Audrey Rouget feels in Metropolitan at the behavior of crude exploitative males. Ruby must eat and ends up gratefully accepting a very hard physical job doing laundry. Retail begins to look like a step up.

So she is in bad trouble. Mike has reappeared and offered to help her, asked her to move in, provided a fancy delicious meal, and we see how that would be easy for her, but she says no. She is proud and wants independence and sees moving into Mike’s house pragmatically as a way out, an escape, easy. At one point she lies and pretends to be ill so as not to let him in the flat with her. She doesn’t kid herself about love. No sentimentalist Ruby. Very late in the movie Mike suggests a job as a central core of life is hollow, just a game, and she says it’s her game and gives her something to do she respects even if it’s “low.” Here is one place the movie is quite different from most conventional movies. When Ruby says she’ll let him give her the meal, but is not sure about the rest of it, the equation of relationship with a well-paid man and selling yourself is made plain.

An in effect deux ex machina saves the day, for one day Mrs Chambers, Ruby’s ex-employer one day simply shows up and wants Ruby back. The employer says she now knows her son lied. We don’t know if that’s true, but Ruby is exhausted and needs better pay. (Later addition, 4/2/07: reading the screenplay I discover I overlooked the connector: Rochelle called Mrs Chambers and told her what had happened.) Her employer wants Ruby back as spring is coming and sales will be going up. Ruby says yes, I’ll come and Mrs Chambers asks Ruby to call her Mildred.

When last seen, Ruby is opening the store in early morning. She’s good at that and enjoys the sense of prestige, respect, and control such an act seems to give. This is the happy or contented ending of the film. Life goes on. She looks about her and says maybe it would have been better to have ended up in a city, but this is where she came and she’ll make do for now. Decent jobs are not so easy come by she’s learned.

Little incidents about teenage life, life for a person in her 20s is depicted. Going to clubs, dancing, eating out. We see groups of college students during spring break having a high old time with the boys parodying a beauty contest and then the girls really presenting one.

Ruby is not virtuous altogether or so easily. At one point she goes on a stealing binge for small things she needs, but then angry at herself for doing this throws them out. She is kind (she takes Betsy when she sees her mocked, kicked and hit, and derided by a bunch of boys in the compound), and, much like the Austen heroines in a number of the movies, introspective, keeps a diary and voice-over is used as she writes in it or thinks to herself about her situation:

During such moments the actess is made seriously to voice all sorts of women’s problems in the modern closed hard anonymous world. To consider how her need for love is used, what friendship is.

I’ve probably not done justice to this nuanced realistic story. Florida is shown to be just as it is in parts: lots of strip malls, cheap stores, hotels, fancy neighborhoods of private houses here and there, but mostly a trash and junk environment around which lush landscape of forests and beaches can be seen. The photography actually makes the place look lovely at times, especially the sky.

Ruby in Paradise is a a good feminist film about a strong young woman who refuses to make the choice of going to live with a man rather than stay in an unpleasant hard (laundry work) job or starve; her choices as a girl without parents or money are severely limited. We see how a young woman cannot act out any free agency because she hasn’t a handle on power or without a family and money elsewhere connections. We see how rough and hard the world really is—as Catherine Morland glimpses in Northanger Abbey, and Fanny Burney’s Evelina and Cecilia experience in the novels named after them. What dis-empowers is not always the individual woman. We see the central role of sex in women’s lives as a thing to sell or to be forced out of her when she is vulnerable (as she often is).

Austen may seem tangential but I think not, or no more than in Metropolitan or Clueless even if there is less literal equivalencies. Some curious parallels. At one point Cher in Clueless talks to a painting of her dead mother; towards the end of the film Ruby too has a painting of her mother hanging in her room and keeps it over the place she writes her diary. The actor who plays Ricky looks like the actor who plays the mean stud-rake in Metropolitan, Rick von Sloneker; the characters even have the same first name

I read about this film either in the anthology of essays on film adaptations of Austen’s novels, Jane Austen and Company or John Wiltshire’s Recreating Jane Austen. The advertisement photo of Ashley Judd is just such another romantic picture of a dreamy, yearning, hurt or vulnerable face as we find in Doran Goodwin as Emma, Emma Thompson as Elinor Dashwood:

As Metropolitan also connects to Emma when the characters against Audrey’s advice demand total candour from one another as part of a card game and people are badly hurt, and Clueless to Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho through the death of Emily St Aubert’s mother and the mysterious veiled portrait, so Ruby in Paradise connects centrally also to Emma (though Mike as a modern Josh-Mr Knightley who is however rejected) & Mansfield Park and many other 19th century women’s novels (Ruby is an unconnected orphan, like Jane Eyre, Margaret Hale of North and South &c &c).

So here is the present line-up:

Transposition or analogies

1) Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s 1980 Jane Austen in Manhattan (an early James Ivory and Ismail Merchant production);

2) Whit Stillman’s 1990 Westerly Metropolitan;

3) Victor Nunez’s 1993 Independent Ruby in Paradise, starring

Ashley Judd, Todd Field, Bentley Mitchum, Allison Dean, Dorothy Lyman;

4) Amy Heckerling’s 1995 Clueless (Paramount), starring Alice Silverstone.

Apparent fidelity

1) 1972 BBC Emma, directed by John Glenister, screenplay Denis Constantduros, starring Doran Goodwin, John Carson, Fiona Walker, John Eccles, Constance Chapman, Debbie Bowen, Timothy Peters;

2) 1979 BBC P&P directed by Cyril Coke, screenplay Fay Weldon, starring Elizabeth Garvie, Irene Richards, David Rintoul, Moray Watson, Priscilla Morgan, Judy Parfitt;

3) 1983 BBC MP, directed by Giles Foster, written by Ken Taylor, starring Sylvestra Le Tousel, Nicholas Farrell, Anna Massey, Angela Pleasance, Bernard Hepton, Samantha Bond, Robert Burbage, Jackie Smith-Wood;

4) 1986 BBC MP, directed by Rodney Bennet, written by Alexander Baron (using Dennis Constantduros’ 1971 script for an earlier TV S&S), starring Irene Richards, Tracey Childs, Diana Fairfax, Bosco Hogan, Robert Swann, Peter Woodward, Amanda Boxer;

5) 1995 BBC P&P, directed by Simon Langton, producer Sue Birtwistle, screenplay Andrew Davies, Jennifer Ehle, Colin Firth;

6) 1995 Miramax Sense and Sensibility, Ang Lee director, Emma Thompson screenplay, starring Emma Thompson, Kate Winslett, Alan Rickman, Hugh Grant, Gemma Jones, Gregg Wise, Elizabeth Spriggs, Robert Hardy;

7) 1995 BBC Persuasion, written by Nick Dear, starring Amanda Root, Ciarhan Hinds, Susan Fleetword, Fiona Shaw, Sophie Thompson;

8) 1996 Meridian Emma, written and directed by Douglas McGrath, starring Gweneth Paltrow and Jeremy Northam, Sophie Thomson, Juliet Stevenson;

9) 1996 BBC Emma, directed by Diarmiud Lawrence, producer Sue Birtwistle, written by Andrew Davies, starring Kate Beckinsale, Mark Strong.

Frank reinterpretation

1) 1940 MGM Pride and Prejudice, directed by Robert Z. Leonard, written by Aldous Huxley & Jane Murfin, based on a sentimental drawing room comedy by Helene Jerome, starring Laurence Olivier, Greer Garson, Edna May Oliver, Edmund Gwenn, Mary Boland, Maureen O’Sullivan;

2) 1987 a gothic Northanger Abbey, directed by Giles Foster, screenplay Maggie Wadey, starring Katharine Schleisinger as Catherine Morland, Peter Firth as Henry Tilney, and Robert Hardy as General Tilney;

3) 1999 Miramax Mansfield Park, written and directed by Patricia Rozema, starring Francis O’Connor, Jonny Lee Miller, Alessandro Nivola, Harold Pinter, Embeth Davidtz;

4) 2005 Universal Pride and Prejudice, directed by Joe Wright, screenplay Deborah Moggach, starring Keira Knightley, Donald Sutherland, Matthew Macfayden, Judy Dench.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Austen-l, Marilyn Marshall:

"Ellen:

Thank you for bringing Ruby in Paradise to everyone’s attention. When I first saw it I was amazed – it’s the only movie I’ve ever seen that was so thoroughly from a woman’s point of view. This is Ashley Judd’s first movie and, because of it, I’ve always loved her.

I liked that she was determined to take care of herself, regardless of the type of work she had to do, and not be reliant on a man for identity and sustenance. At the beginning, when she’s hightailing it out of her road in Tennessee, doesn’t a bare-chested, bare-footed man in blue jeans throw a boot after her car? I always remembered that as providing the impetus for her need to change her approach to life.

She settles in Panama City on the Florida Panhandle, which is known in some circles as the Redneck Riviera! She arrives during off-season and when Mrs. Chambers says that she isn’t hiring, Ruby convinces her to hire her by her determination and desire to work. Later Mrs. Chambers tells her that she hired her because she was hungry and reminded her of herself.

The movie has a melancholy air about it (somewhat like the Amanda Root Persuasion) and there is a plunge into depression when she hits bottom. Nonetheless, you are drawn into her quiet struggle to make a place in the world for herself on her own terms. She manages to create a secure place in her small cabin with her grandmother’s quilt and rocking chair—and houseplants.

By the end, she has taken on the challenge of teaching Mike what she knows about life. I felt he was overbearing and sometimes condescending in his attempt to school her to life, but that may be just my feeling. Like Ruby, Mike had created a small domestic world full of security and personal fulfillment, so maybe in the future they were able to merge their personal worlds.

Anyway, like an Austen novel, Ruby in Paradise has a seemingly simple story to tell, but in time you become aware of the undercurrents that tell a deeper emotional tale.

Marilyn"

— Sylvia Jan 3, 12:31am # - Thank you for the thoughtful reply, Marilyn. Yes Mrs Chambers says she recognized herself in Ruby when Ruby needed a job: after all Mrs Chambers is divorced. And again when she says she understands what happened when her son aggressed at Ruby, she says he’s her husband all over again; she once had to live with that (lying, indifference, promiscuity).

I like the parallel with Persuasion but feel it’s too general to adduce. Many women’s novels are deeply melancholy and about loss, subjective in the same way. One needs specific or literal details for more equivalence: Mike as a reframing of Henry Tilney and the close anticipating of Josh in Clueless; the picture on the wall of the dead mother recalls NA and Clueless and Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho too -- though that might not be meant; still as Heckerling saw deeply and knows the literature of the era through Austen, why not Nunez?

I would like to see more parallels with other of Austen’s novels. So many of the adaptations bring in material from more than one novel, but I couldn’t find much beyond the picture and Mike as Josh (=Mr Knightley as well as Henry Tilney). Maybe the young girl in the compound who is so young and has let herself in for abuse, Debra Ann, could be a parallel for Georgiana Darcy, but there is no pattern beyond the reference which is parallel to P&P. One detail is not enough: you need to see a confirming paradigm which both works share.

I felt at the end we were to assume Ruby and Mike were not going to become a couple again; Ruby says they are drifting ever more apart. The film thus anticipated some more modern ones where the girl walks away: Maria Full of Grace, Since Otar Left. While I think the film is highly unusual in its unambivalent presentation of a woman’s point of view genuinely apart from how males see her, I think there are others. Except for Emma Thompson’s Sense and Sensibility not I would say among the Austen’s films: in these it’s a matter of seeing the contradictions and hard choices, which are in all the films for supporting male hegemony as the best for the women characters, but among other modern films and film adaptations too. These are often films made by women, e.g., Friends with Money and Lovely and Amazing by Nicole Holofcener, but you can also (rarely but it happens) films made by men.

I was particularly delighted to see NA used centrally. It is still underappreciated. By comparing film adaptations we learn. While the 1986 NA was a very free adaptation, we can see by looking at this transposition, that realism is central to Austen’s conception and without it, the real meanings of Austen’s text are lost. We are left with gothic pastiche.

There was a paper at the MLA on NA and it made me remember how important history and real terror are to real gothicism in Austen’s novels. The references to the riots, Eleanor’s willingness to and real interest in history (and she is tyrannized over by a mean materalistic cold father, alone without friends and mother), the general’s sudden way of turning Catherine out so that we see how in real life suddenly security is cut away from us and we are nowhere (as was Ruby once Ricky simply told his mother Ruby had gone out with him). How are we to understand (and trust) in people says Catherine if their words don’t at all reflect what they mean?

E.M.

— Sylvia Jan 3, 7:49am # - Someone who visits this blog and doesn’t want to be identified has reminded me there’s an 18th film available, one of the apparent fidelity type: the 1971 BBC several-part Persuasion, directed by Howard Baker, screenplay Julien Mitchell, starring Ann Firbank as Anne Elliot, Bryan Marshall as Captain Wentworth.

I have seen this once and thought it simply poor. I might feel differently now, but remember finding it did not exploit filmic cinematic techniques at all and evidenced an unwillingness to present the heroine, Anne, as haggard, depressed, lost, so that there was nothing to be uplifted from; similarly there was a reluctance to present the martial hero type (supposedly) Wentworth as a man of sensibility.

So I probably won’t rewatch it—at least for now.

E.M.

P. S. In all cases I'm talking about available films; there were earlier P&Ps, S&Ss, Emmas, but either there is no extant film version or the film version is not available.

— Sylvia Jan 3, 5:11pm #

commenting closed for this article