Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

The Poetry of the _S&S_ movies · 28 October 07

Dear Harriet,

I’ve been wanting to write about 3 parallel key scenes in the 1981 BBC S&S, 1995 Miramax S&S, and 2000 Sri Surya I Have Found It because these show how Austen’s S&S lends itself to poetic development of peculiarly women’s themes through film.

To wit, all the Austen movies take up the experience of loss as a challenge, an opportunity for memory to work upon, almost a gift to live through, partly because this idea at the heart of the structure of many mini-series recurs in Austen. Austen’s Elizabeth Bennet suggests to her Darcy when he says he cannot understand how she can take pleasure in rereading his harsh letter to her, that the past’s mixture of pain and pleasure “gives remembrance its full poignancy” (P&P, 3:16:368-69); when Austen’s Captain Wentworth is surprized that her Anne Elliot wants to remember what happened at Lyme, she counters “The last few hours were certainly painful … but when the pain is over, the remembrance of it often becomes a pleasure” (Persuasion 2:184).

In both the mini-series 1981 and 1995 Sense and Sensibility, this idea finds expression in the choice of poetry the two different Brandons (Robert Swann and Alan Rickman) recite aloud to Marianne (Tracey Child and Kate Winslett). In the 1981 Sense and Sensibility Brandon sits down by Marianne’s bedside while they are still at Cleveland, and in their talk it emerges he is a genuine reader of Cowper, Scott, the “majestic Milton” and “demi-god Shakespeare” (his words), and he recites spontaneously (from memory), the first lines of the song from Shakespeare’s Cymbeline (IV:2:258-281), where loss is no disaster, but what is longed for is a release like that granted by death’s sleep:

“Fear no more the heat of the sun,

Nor the furious winter’s rages,

Thou thy worldly task has done,

Home art gone and ta’en thy wages …”

She hears and recognizes him for something of what he is (his worth) for the first time:

In a scene in the 1995 S&S, which follows directly upon Marianne’s nearly automatic acceptance of Brandon as a friend and future possible lover, we see them in the garden together, he reading aloud to her from Spenser’s Faerie Queene (V:2:39-43):

“Nor is the earth the lesse, or loseth aught.

For whatsoever from one place doth fall,

Is with the tide unto another brought …

For there is nothing lost, but may be found, if sought …”

She hears him and the sentiments:

A famous modern sonnet by a woman poet captures this idea startlingly frankly: Elizabeth Bishop’s villanelle, “The art of losing isn’t hard to master … (a letter on the pure emotional pain of the 2007 ITV Persuasion). I’ve quoted Bishop’s poetry on this blog more than once.

The 2000 Tamil adaptation of Sense and Sensibility as I have found it takes up this poetic vein in another way. Three weeks ago at the WSC I was lucky enough to attend a partly dramatic reading, partly enactment of an abridged English translation (reputable) of one of an ancient Indian (Hindu) play, which was called The Recognition of Shakuntala and is attributed to Kalidas. It is a story taken from an episode in the famous Mahabharata. It shed light on the curious retitling and mood of the Bollywood-Tamil adaptation.

In the adaptation the Marianne and Willoughby characters, Meenakshi (played by Aishwarya Rai) and Vinod (Dino Morea) dance a spectacular song on the water (also a woman’s image) and the refrain is “I have found it.” The meaning is actually they recognize what love is, what they have been seeking for and are ecstatic with happiness. (Rather like the opening—excuse the cross-reference but it reminds me of it—of Sondheim’s Passion where the two lovers go on about “So much happiness.”). But in Austen’s book and this film Vinod (Willoughby) betrays Meenakshi (Marianne): Vinod suddenly disappears because he wants to marry a wealthy woman; the marriage has been arranged for hiim and will provide an influx of money for his ailing businesses. This loss, this disaster gives Meenakshi time to see her real love is for the Captain Brandon character, Captain Bala (Mammootty), the crippled veteran of a savage war (he lost his leg in a landmine accident—echoes of Isabelle de Montolieu’s originating character in Caroline de Lichtfield, the novel which is one source for Austen’s story). As in Austen’s (and Montolieu’s) versions, Captain Bala is an older and not handsome man who is far more romantic and has more real poetry in him, is a man of real sensibility and ethical idealism, kindness, than the superficially glamorous Willoughby.

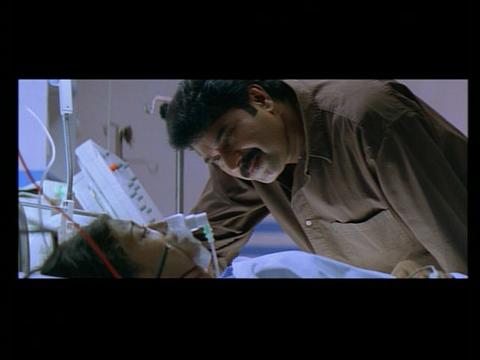

Here is the hospital scene (a parallel to the faithful S&S films) where Meenakshi has been taken after a bad accident (she fell through a manhole in the streets, too stressed to take notice); we see Captain Bala come to her and tell her for the first time ever he has tried to pray for her (he was devastated by what he saw and what happened to him while in the war the film opens up with):

In a subsequent scene we see her thinking about him:

This leitmotif in the plot-design of I have Found It is paralleled by the Elinor and Edward characters, Manohar (played Aith) and Somya (Tabu): Somya (Edward) is forced to give her up by his parents and his own desires to make a film; Manohar’s family (as Austen’s Dashwoods) lose their home, and go to Madras where she is the only one with the strength of character, skills, and determination to find a job making a good living. She ends up a well-paid computer programmer. So when Manohar and Somya finally get together at the end, if the near loss of one another and growth they have known is in literal events an imitation of the 1995 S&S (he comes to the door, she runs away in tears), the feel is that of Austen’s own Anne Elliot and Captain Wentworth, now mature people finding one another again at the close of the novel, Persuasion (and also all the Austen movies, whether faithful or analogous). The refrain of “I have found it” recurs at the Tamil movie’s close.

The great advantage of adapting a great book by a woman for women viewers is what the respect given the book as well as its depths of content allows. The parallel scenes show the high romance of the films: what is recited reveals the deep melancholy of the 1981 S&S, the qualified mature optimism of the vision of the 1995 S&S, and how in Indian culture still, religious texts function as secular ones do in western culture.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Though I don’t think the 18th century translation of this Hindu tale influenced Austen’s novel as one of Austen’s book’s point is Austen’s Marianne learns she made a bad mistake: elsewhere also Austen writes against the idea of the magical importance of first impressions; through the treatment of Eliza Williams and Brandon she deplores the way men treat women as suspicious sex objects.

Still it’s interesting to know there was an 18th century translation of the Recognition of Shakuntala.

It was by Sir William Jones and is online:

http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00litlinks/shakuntala_jones/

For information on Jones:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Jones_(philologist)

Whether the book made it to Austen’s local circulating libraries, we cannot tell; Austen does tend in those letters we have left and in the novel cite novels (modern type and romances), plays, and memoirs, conduct books, travel books, English poetry. But she had her aunt’s (probable ex-lover,) William Hastings (and George Austen’s uses of him for patronage), and the intimate friendship connection through Eliza de Feuillide Austen (who does not seem to have been a serious reader herself though).

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 29, 8:50am #

commenting closed for this article