Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

The 1st mini-series film adaptation of _Sense and Sensibility_ · 31 July 08

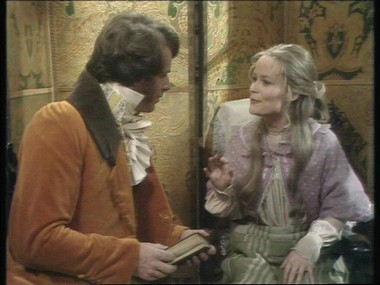

Robin Ellis as Edward when he sees Elinor coming into his lodging after his mother has disinherited him (1971 BBC S&S)

Dear Friends,

A few days ago Ms Place sent me copy of a blog she means to put on Jane Austen’s World: Anguish and Comedy in Sense and Sensibility, 1971: a framing of 3 postings I wrote on the first mini-series film adaptation of Sense and Sensibility: produced in 1971 by Martin Lisemore, it was directed by David Giles (who directed the 1983 BBC Mansfield Park) and written by Denis Constanduros (who wrote the 1972 BBC Emma).

I decided I would write complementary blog on this S&S to accompany hers. After watching the 4 part film three times, the third time slowly, taking down the screenplay and capturing lots of stills, and giving myself over to its aesthetics, moods and words, and images, I’ve decided that while it’s not a masterpiece of filmic TV art, it is an intelligent moving drawing-room comedy rendition of Austen’s novel. As with the 1972 BBC Emma and 1983 BBC MP, it’s hard to talk about the ‘71 S&S the brief compass of a blog, for highlighting bits and pieces goes against the grain of what makes these earlier films effective: that is, their slow nuanced development in depth over the course of several parts, and their reliance on perceptive subtle scripts.

My three postings are about how this 1971 film keeps the same proportions and emphases as Austen’s novel (for example the 2 long scenes in which Lucy cruelly inflicts on Elinor how long she has been engaged to Edward, the knowledge that he has if not openly lied, misled her, and a promise which makes Elinor’s love a tabooed humiliating one); about how it conveys the anguish of the Dashwood young women through the comedy of Mrs Jennings’s presence as in Austen’s novel (it turns epistolarity into comic dramatic monologue); and how it emphasizes the humilation of Elinor at the hands of Mrs Ferrars, with Marianne playing the part of a Cassandra who insist on crying out the truth to all about her, a truth which no one wants to hear and doesn’t help Elinor to make known, again as it is in Austen’s novel. None of the three costumed film adaptations afterwards attempt all this, but choose rather to have a holistic consistent stream of feeling which carries the viewer along emotionally.

I earlier wrote about how this film also anticipates some changes we see in all the films, e.g., Brandon is brought forward to be at the assembly when Willoughby decamps; Marianne is shown as gradually (as in the 81 film) falling in love with Brandon based on their shared love of books and conversation.

For this complementary posting, I thought I’d type out a transcript of Willoughby’s confession. Brilliantly acted by Clive Francis, this long scene is the climax of the film. It shows Constanduros’ gift for naturalistic talk which yet takes in Austen’s lines and remains true to her meaning and yet clearly in modern thinking language.

From Part 4, Resolution, 02-03, Scene 10 (from Austen’s S&S, 3:8 or Ch 44): Cleveland house, stairwell, downstairs vestibule and front room by fireplace:

1. Bridging shot: Elinor hastening down the stairs.

2. He is seen from the back, turns and she sees it is Willoughby. She stands stock still.

3. Dialogue.

Elinor (whispers) “Willoughby.” (She turns to go upstairs, a look of grief on her face.)

Willoughby: “Bear with me for five minutes” (pleading yet proud tone).

Elinor (set face). “No, sir.”

Willoughby : “But I’ve driven all the way from London.”

Elinor (whispers): “From London?”

Willoughby: “Marianne. “I’ve learned just now from the servant who left me in that she is a little better. But is it true? Is it rally true? For God’s sake tell me. I mean is she out of danger? or is she not …”

Elinor: ‘Yes we hope now that she is.”

Willoughby (looking down): Then God be praised. If I’d known as much a whle back … but since I am here can I ask you just spare me a few moments.”

She still starts upstairs.

Willoughby: “Miss Dashwood!”

Elinor stands still, thinks and then turns: “Very well.” (She goes downstairs and to couch.) “You had better sit, had you not?”

Willoughby: “No thank you.”

Elinor. “Then I will.”

Willoughby paces over to the fireplace and stares inward for a moment.

Willoughby: “When I first became intimate with your family in those happy far off days, I confess that I had no other object than to pass my time in Devonshire as agreeably as possible. Your sister’s lovely person and interesting mannres could not but please me but to be honest I had at first no serious design in returning her evident affection.

Elinor. “Mr Willoughby, it is hardly worth while your telling me all this. Please do not pain me further in this manner” (she gets up to go).

Willoughby: (loud). “No please! I insist on you hearing the whole of it. Please!” (he pulls at her, but has a soft appeal in his voice)

She sits again; close up of both their faces begins.

Willoughby: Now this was at the very beginning but very soon even I profligate thoguh I was and am found my heart truly moved by your sister’s sweetness” (This Marianne thoughout is played as an idealistic innocent girl loving poetry and books against the worldliness and greed and manipulation of everyone else).

Elinor: “Then you did at one time genuinely believe yourself attracted to her.”

Willoughby: “Is there a man on earth who could have resisted her? Certainly not I Miss Dashwood. No, the happiest hours of my life were those that I spent with her. When I still considered my intentions honorable and my feelings blameless.

Thinking back to “the happiest hours … ”

I had determined to engage her alone to justify the attentions I had so invariably paid her.”

Elinor: “But you didn’t.”

Willoughby laughs nervously. “Alas, to what depths can one go in self-deception. (camera back and forth on her appalled face as he speaks.) It was about this time you see that certain matters became public you understand resulting from a previous youthful indiscretion. Do I make myself clear?

Elinor (biting look) “You do. though how you have the effrontery to speak of such amtters is almost beyond my comprehension.”

Willoughby: (fierce) Because I must be absolutely frank with you but if you think for one moment Miss Dashwood that I feel no shame then I can assure ou you are quite wrong.”

Elinor. “Go on.”

Willoughby: (sniffs as if tears coming to his eyes). “Oh God what awful day when I had to tell your sister that I must return at once to London will ever remain etched in my mind (nervous tone). Your mother I remember rubbed salt in the wound by her kindness in asking me to come back. But the situation wqas by that time such that there was no possiblity of returning. Imagine my state of mind on that long trip back to London. Your sister’s affections destroyed. My inheritance gone and all my affairs completely in ruin.”

Elinor: “You situation was truly deporable, Mr Willoughby, but hardly so desperate as that of the poor creature whose life you had so thoughtlessly ruined.”

Willoughby: “Miss Dashwood, my conduct was extremely wrong I’ll admit but in these matters the fault is very seldom solely on one side.

Elinor. “You will do nothing to improve your case, sir, by trying to share the blame however justly with a poor yong woman whose sufferings must be so immeasurably great than your own. This is not worthy of you.”

She reproaches him for justifying himself

Willoughby: (he smiles slightly) “Strong words, Miss Dashwood, but well-merited I fear.”

He remembers her rigor of old

Elinor: “And is this all?”

Willoughby (another sniff and more held-back tears). “Indeed it is not all. I have not confessed the worst of it yet. For having reached the very depth I decided that the only way of recovering my lost fortune was through marriage. Yes, I see the look upon your face. Well. If it is any comfort to you, Miss Dashwood, I have been amply repaid for my pains. Amply now then does that bring you any satisfaction?

Turning away.

Elinor. “No sir, it does not.”

Willoughby: “Then to come face-to-face with your sister like that, as beautiful as an angel holding her hand out to me and asking me for an explanation with those bewitching eyes looking up into mine (fond smile, nostalgia, some memory) and Sophia on the other side as jealous as the very devil. Good God! what a contemptible figure I cut. (Moves back and forth). That was the last look I ever had of Marianne and yet when I thought of her today as really dying it was a kind of comfort to me to imagine that I knew exactly how she would appear to those show saw her last in this world. She was ever there in my mind before me as I travelled.

Elinor sighs and addresses him: “And the letter, sir. How pray do you explain that?”

Willoughby: “The letter? (puzzled). Oh, oh, yes, the letter (hand on his forehead). (Moment pases). Do you not admire (he smiles) my wife’s style of compostion.”

Elinor: “Your wife?”

Willoughby: “Delicate, tender, truly feminine, is it not”

Remembering his wife that night

Elinor. “But the hand was yours.”

Willoughby: “Written at her dictation I’m ashamed to say.”

Elinor. ‘You are very wrong, sir, to speak of Mrs Willoughby in this way. You had a choice it was not forced upon you. Your wife has a claim to your politeness at least, whatever her merits may or may not be, and to speak so slightingly is no great atonement to poor Marianne.”

Willoughby (he smiles again and voice resonant) “Once again you’re right. I stand rebuked. You are very harsh are you not in your moral judgement?” (camera on her face working). Well goodbye Miss Dashwood. I thank you for bearing with me for so long. He begins to rush off, she gets up showing concern for hiim

Elinor: “You are not driving straight back to London?”

Willoughby turns and suddenly speaks familiarly: “Oh yes and tell Marianne …

Then remembers that he will not be seeing her again tomorrow or ever: “Tell your sister from me that she has never been dearer or more precious to me than she is at this very moment.”

Elinor: “I will.” We hear rain again.

Willoughby: “Thank you. Goodbye Miss Dashwood. God bless you.”

Elinor: (soft voice). “Good bye.” Facial shot on her.

She watches him turn and go out the door.

By quoting different lines from Willoughby speech (which are there), it comes out differently; much more subjective pyschologically reflective ones chosen. He is a profligate and embittered at his loss and makes that explicit in words—idea is in 08 S&S but all that emerges is what realistically would emerge, pity men, not the high minded reasoning. Despite Elinor’s clarity she is most kind to Willoughby and just about forgives this rake.

Ironically, this powerful scene shows this film despite its strong emphasis on women, still climaxes in a long scene of male anguish and loss. It also makes an instructive comparison with the same scenes in the other costumed historical romance films (and absence thereof in the ‘95 Miramax S&S, written by Emma Thompson). We can see how the deep structure of each film comes out of its inward psychological patterning.

In a nutshell, while Willoughby’s confession is an unexpectedly revelation in the ‘81 BBC S&S (written by Alexander Baron), the ‘81 confession is shorter, less nuanced (Willoughby is much more sheerly angry and resentful), and it doesn’t have the prominence of other memorable male scenes in the last part are memorable: Edward’s (played brilliantly by Bosco Hogan) intense pain in a long scene where he accepts Elinor’s (Irene Richards) offer of a place on Brandon’s estate (the “making of him” this Edward bitterly says):

Edward (Bosco Hogan) told by Elinor he has a living, his face twists in ironic self-scorn

and Brandon’s (Robert Swann) emergence as a deeply poetic sensibility over a discusson of Shakespeare’s “Fear no more the heat of the sun …” (Cymbeline) and Milton.

The climax in the 1995 S&S is Marianne’s (Kate Winslett) traumatic walk through the green landscape in storm, her illness near death and Elinor’s (Emma Thompson) agon until dawn.

Dawn, Elinor’s (Emma Thompson’s) agon comes to an end; bright

light

In the ‘08 BBC/WBGH S&S (by Andrew Davies) Willoughby’s (Dominic Cooper) confession just reinforces, or makes explicit what we have seen already in the scenes with Brandon (David Morrisey where Willoughby behaves like a cru), in the duel, in what Elinor (Hattie Morahan) has been told: he’s an egocentric utterly selfish self-pitying sneaking shit. The climax of the ‘08 S&S is Elinor telling Marianne (Charity Wakefield), she has know about this for 4 months; it’s the climax because of the silent emphasis on Elinor all along so the movie is the stages of Elinor’s grief from death of father through new love, to those final heart-rending scenes in the last part where we see her standing alone enduring her pain and loss with a smile (on the cobb, buying fish, seated on a bench by the sea, walking).

Elinor (Hattie Morahan) believing Edward has married Lucy, faces life alone, endures on. This is my favorite moment in this film.

**************

I conclude with calling attention to further remarkable moments in the ‘71 S&S

Part 1: Farewell to Norland

Paratext of 01-06 is the scene of Marianne fleeing house, the carriage, going off, her face upset and loss, and then the women in the carriage, each with her memories:

Marianne bidding farewell, a repeating paratext with 18th century music in the background

The Dashwood women riding out of Norland!

And then (Part 2, opening), the arrival: grief, loss, bewilderment, stoicism, they cling to one another upon arrival, displaced women. Scene of women inside the carriage is iconic, all three have it at some point; the costumed ones in the first part, one woman a widow; displaced women also in I Have Found It.

As O1 begins : Paratext within piece is of Mozartian music and lovely pond with lillies on it: an elegant far-off rococo vision, picturesque, dainty; opening

First still of film, accompanied by Mozart’s music

Interpretation is of Elinor as sheerly sense and self-control, strongly moral, older idea of anti-sexuality in Austen going on, with Marianne as rebellious teenager. There’s a wonderful dialogue about the picturesque as Edward stands contemplating Elinor’s drawings. They discuss them with Edward admiring but not sure what to say, and when Marianne comes in, her insisting her picturesque perspective (said by Elinor to give her sketches originality) only offered a shape but not the details and feel of what we see. As with all the S&S films a great deal is made of Edward quickly so as to estabish the importance of this relationship; and right away she is in love with him. In this one he stammers.

Actually to have a new or added character like Mary (Esme Church), the servant at Barton cottage is unusual and draws attention to itself; the others don’t add a character. The servants are mentioned as Thomas and someone else (young woman) and they are kept in bounds in ‘81 though given personalities; do not appear in ‘95 (savings on actors) and simply appear and disappear without explanation in ‘08, or Thomas does. Jim suggested how it’s okay to delete scenes from Shakespeare but it’s not okay to write a new one and stick it in. There’s also a strong prejudice against adding lines.

I’ve figured out why Mary is there: it’s in E.H. Young’s Jenny Wren: she’s there to show how they’ve come down; this is the kind of servant they have to put up with a home-y woman they have to be polite to, they are dependent on her services. This is how it would have been seen in the 1940s and is a bit dated for the ‘70s, but it’s the reason she’s there and so emphatically what they have to confront. Instead of the false run-down cottage and the overopulent house, Constanduros has sought to convey their coming down by the servant and the narrowness of the house, its smallness.

Constanduros has a very great gift for naturalistic dialogue and it emerges in the Willoughby recue scene; his helping them the least romantic and overdone of any of them; he is really simply being decent and kind, already romance in eyes of ‘81, ‘95, ‘08. When Marianne says goodbye to the curtains, it’s really funny—as nowhere else do any of the films get any truly comic mileage out of her absurdity without making her unlikeable:

Marianne: “Goodbye, curtains!”

Part 2: Parting and Journey

Paratext for Part 2, 01-06 where you click each is scene in gardnen where Elinor comes to cheer Marianne, Marianne becomes intensely anxious as she suddenly insists it’s Willoughby, her disappointment strongly enacted for the first time, but then we turn to Edward and Elinor’s working face.

A repeating paratext

As 01 begins: paratext within piece is very Mozartian music and as in 72 Emma, the paratext has changed to reflect new place: flowers in slight wind, Barton cottage, suggestive of girls at risk coming home from Delaford without Marianne

That it’s over so quickly between Marianne and Willoughby is more realistic, really what such a romance might have felt like; the writing makes Willoughby more genuinely gentle and remorseful and Mrs Dashwood (Isabel Dean) more wary and suspicious, reflecting an early time which at once had more sympathy for men and less for sexuality itself. The parting is with Willoughby and the journey is to London.

I find same ability with irony in ‘72 Emma in scenes where Edwards disclaims ambition and Marianne says “quite right, Edward;” we are to laugh at them, if not hostilely; the dialogue in ‘95 is sympathetic and in ‘81 and ‘08 Edward is depressed. Irony at central characters reminds me of ‘72 Emma. How a remark suddenly dramatized comes alive: I had not noticed Edward’s comment in Austen that he thinks by nature he is intended for low company. Heis thinking how he makes it with Lucy and how awkward he is with Dashwoods and in society. We are to see he is mistaking his lack of ease among people of gentility as a class issue, when it’s a character issue. He can’t stand his mother and sister nor Lucy really (she is hypocritically putting him at his ease)

The scene where Lucy (Frances Cuka) visits and tells Elinor is perhaps the best of all the scenes; it is given the most length and depth and is done beautifully by both women with no helps in music or anything else. Just sheer acting. .

When Elinor softens Marianne’s refusal to play cards and going over to harpsichord by saying Marianne cannot keep away from that instrument, it has a perfect tone, she is probably lying. The viewer is here expected to see this as an example of “all the burden of lying fell upon Elinor.” A good detail example of how film adaptations finally expect you to have read the book for their full effect. In a later scene the actress winds up her ball of thread so intently while asking Elinor if Elinor would ask Mr Dashwood for a living on Norland property, you’d think she had Edward in her hands and was choaking him, all the while Marianne plays some frenetic Mozart very loud on a harpischord.

Lucy thwarted by Elinor’s refusal, irritated by Marianne’s music, puts her ball of yarn in knots, becomes angry and confused

The pain on Elinor’s face seeing Lucy’s cruelty (she has a way of meaning pinching Nancy who is a coward) is striking. Seeing this, Lucy calms down but cannot stop the tears from forming in her eyes:

Truly brilliant writing and acting for Lucy (Frances Cuka). We see how hard and cruel she is when offstage, her temper, and also her vulnerability, her desperate need and humanity, everything in the outburst, rolling of wool, the frantic music from Mozart behind. A great scene!

Brandon also presented as a shy tongue-tongued, self-effacing man. The trouble is it’s too many for a public program and his sensitivity and sensibility (in the book) is downplayed. he is rather withdrawn and melancholy. troubled by his past which we eventually learn. It’s not wrong; it fits, but it does not make for exciting TV watching :)

In this version at the assembly Willoughby at first tries to avoid encounter strongly and then he offers super polite way of talking and a lie she is expected to take up (“My note was not mislaid I hope”), but Marianne cannot play this game.

He offers social signals to save face

Ah that is why I love this book. I love both heroines. And when she blurts out truth loudly: “I’ve had no note nothing,” he realizes it’s useless to try to save face and walks away.

She does not think to say anything but the truth

By contrast, in Austen he really snubs her and this comes out strongly in both ‘81 and ‘95 films.

Part 3: Sisters in Misfortune

Paratext of 01-06 is scene of Lucy being favored by Mrs Ferrars and preening: central humiliation of Elinor with Marianne as Cassandra like figure saying truths no one wants to hear and don’t help

As 01 begins: Paratext is broken flower and delicate lace handkerchief and then we see Elinor asleep, Mozartian music stops when she begins to waken

The long sequence of illness near death

Marianne delirious with fever

Part 4: Resolution.

As 01 beings, an iron table, candle, bread and thin cake, and the the camera moves out to show us Edward’s poor room in the attic of an inn, the stairwell and Elinor making her way up.

Edward reading in the lodging attic where he retreats after his mother has cut him off; he hears Elinor knocking at the door

The scene outside Marianne’s sick room where Colonel Brandon and Elinor speak on stairs in both 7’1 and ‘81 S&S; in ‘81 it’s beautifully melancholy and poignant. Here not so; this actor (Richard Owens) lacks this soft plangency, when Elinor bursts into tears on his neck just before he returns to Delaford Abbey. Austen just has a sad line about how the Colonel “took his solitary way” after they parted as “cordial friends,” Ch 46, p. 290. Of the adaptations, the ‘81 film is the finest here.

Marianne presented as naive idealist throughout. An implied background of money and corruption which is nowhere as strong in the others. Willoughby even now prolifigate; he can’t resist her sweetness, the way her mother looks at her when she talks of how she’ll spend her life reading …

We are told in S&S Brandon a reading man but these delicate book reading scenes between Marianne and him and references to private libaries of Middletons or Brandon wholly made up.

Brandon and Marianne beginning to form a deep friendship over books

There is a poignant and delightfully comic scene where Edward tries to kneel down to ask Elinor to marry him, stumbles and even stammers, and she says “No!” distressing him until he sees she is worried over his trousers (she worried about the rain when Marianne persisted in running out into the wide meadow where they encountered Willoughby and then her looking up plangently as he says, “who could resist you?” Constanduros sympathizes with her anxious prudence.

Elinor putting a cloth on the ground so Edward will not ruin his trousers on the wet gravel

Edward loving her for her unashamed humility and prudence

Meanwhile inside the house,

Marianne is beginning to fall in love with the man who loves her

The last still is a quiet one (as it is in the ‘72 Emma, also a drawing-room comedy, also by Constanduros): the two young women hugging:

Fade Out.

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Someone has already asked what in my view is the climax of the ‘00 I Have Found It film: I’d say the antepenultimate scene between Captain Bala (Mammootty) and Meenu (Aishwarya Rai) where she reveals to him that she loves him, aggressively insists he believe her, allow her to help him down the stairs, and at the bottom stands close to him, until he yields to admit his deep love for her—and in this film equally important a new faith in God who has meant him to suffer the way he has all film (the film begins with his near death from a landmind and loss of the bottom part of his leg).

The trajectory or deep underlying story here is quite different from the costumed historical dramas. Mano (Ajith, the Edward character) gets to make a film and secure a place for himself in life before returning to Sowmyra (Tabu, Elinor) and in a scene imitative of the one between Edward and Elinor in the ‘95 film asks for understanding and forgiveness with a door inbetween them as Sowmyra weeps away.

E.M.

— Elinor Jul 31, 10:54pm # - I’ve just read Ms. Place’s blog and will repeat here what I said there: I attribute the aesthetics and nature of the presentation of these older film adaptations to the experience the writers, directors, actors, all had had before they began these mini-series. Constanduros was a well-known playwright and had a real success with a poignant but comic drawing-room comedy in the 1940s (during the war) called Acacia Avenue. Many of the people working in the BBC in those years also worked in the London theatre and radio plays. On TV they were the people doing the Wednesday night “play.”

Nowadays writers, actors, directors come from the movies, and movie techniques are trumping or influencing (sometimes to the bad) stage plays. Plays are not realistic; they are symbolic and communicate through words and intense dramatic long clashes of actors. Movies nowadays rarely have really long scene of this type. The older mini-series do have them.

There are some marvelous film adaptations of this era. You have to lend yourself to their quietude and subtlety. One I saw recently The Stalls of Barchester Cathedrale, an adaptation of an M.R. James’ ghost story. Clive Swift (who played Bishop Proudie in the 1980s mini-series of Barchester Chronicles and more recently King George in Aristocrats, 1999) is the central terrorized learned clergyman.

There is so much gain in the new techniques we lose sight of what is lost. Deep humanity in the presentation of characters in-depth and various (comic, subtle, nuanced) psychologies with a requirement of great acting.

Ellen

— Elinor Aug 2, 9:17am # - From Vic:

“Ellen, I know what you mean about replies – they add a different perspective and start a dialogue. Ah, well. I’m glad we got to discuss my aversion to the 70’s flicks. Not that I don’t watch them, but I have a hard time enjoying a film in which the sets and costumes seem so wrong. I just watched Vanity Fair last night with Susan Hampshire. The costumes were actually spot on, and although the sets looked staged, I rather enjoyed the 1972 version more than the recent Vanity Fair adaptation with Reese Witherspoon.”

— Elinor Aug 2, 11:34am # - Dear Vic,

The availability of Davies’ Vanity Fair and the film with Susan Hampshire demonstrates the lack of respect for movies, and how what’s available is shaped by what’s thought to be famous. Thus Hampshire still has fame so the VF with her is available, and Davies is the darling of the BBC.

But I’ve read and believe that the best ever made is a later 1980s one by Alexander Baron, a fine novelist who did other screenplays for versions much admired—like “A Scandal in Bohemia” with Jeremy Brett,” one of the Jane Eyres, an Oliver Twist with Eric Porter (who played the Count in Jewel in the Crown) as Fagin. You can’t get it. Baron has no fame. His biographer says he never attended parties, did not sell himself; plus he was a socialist an that's nowadays a no-no.

Austen’s name is now so supreme, we are getting these older versions back in print, but only “Jane Austen” and “Charles Dickens” have this kind of pull in the reprint circuit of DVDs for films based on older high status books.

Ellen

— Elinor Aug 2, 11:37am # - Thank you so much! What an immense amount of trouble you have taken in order to give us this.

What is your blog address?

Aurelia

— Aurelia Loveman Aug 3, 8:31pm # - They do take time, Aurelia. Thank you for the gracious comment, which means a lot to me.

The address is on top.

Ellen

— Elinor Aug 4, 9:16am #

commenting closed for this article