Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

ASECS, Richmond: the 18th century on film · 12 April 09

Albert Finney as Tom Jones leading the charge (1963, Tony Richardson’s film)

Dear Friends,

As I’ve now finished updating my Clarissa website (except for a planned brief essay on Anna Barbauld as the first important voice on Richardson and his first editor and biographer), and told of my adventures among friends in Richmond, it’s time to write about the ASECS sessions themselves. For the BSECS this year I went chronologically (google for this as “site:moody.cx BSECS”): here I’ll group the summaries thematically, and first up are the sessions on film.

John O’Neill was the panel chair of the session at which I gave my paper, “How you all must have laughed. Such a witty masquerade: Clarissa 1991: “The Eighteenth Century on Film—I” (Fri, 4:15 to 5:45 pm). Since I was too nervous to take detailed notes, I can give only the gist of the other two papers. The first paper, excellent, suggestive, by David Richter was on Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice. Prof Richter kept up a stream of carefully chosen clips with music heard as he talked over what we were seeing: he showed that Wright was developing visionary contrasts of inside and outside to project a numinously romantic world, which was meant as a modern rewriting (or commentary) of Austen’s book.

I have now just rewatched (two and three nights ago) Wright’s Atonement and find that Prof Richter has explained central aspects of the experience of this movie too. In both movies the characters’ subjective inner worlds are made into landscape projections of their moods, with rapid & often wordless cutting & juxtaposition. Ian McEwan’s book Atonement imitates Virginia Woolf in its interiority and techniques, alludes to Northanger Abbey, uses picturesque landscape and poetry, and is a masculinist rewrite of Clarissa, the film which is itself loaded with letters (like the 1991 film Clarissa), and uses the sound of a clacking typewriter throughout also to suggest to us what we are seeing is the product of Briony’s writing a novel; it’s symbolic, visionary, moving from rich interior to nightmarish exterior.

A characteristic visionary scene from Wright’s Atonement: Keira Knightly as Cecilia Tallis

The third paper was given by Beatrice Fink and it was a good thing she came last or I might not have gotten to give my paper (after all the work I did). She took the rest of the time after I finished, just ignoring all signals she had gone overtime. She had not made clips or stills, but (as with the woman who gave a paper on De Sade movies), expected the audience to watch her find sections in her DVD which exemplified what she wanted to say. She didn’t have a clear line of argument. She seemed to be asking us to see that Patrice Leconte’s Ridicule is a satirical take on how shaming (ridicule), masquerade, nasty gossip and gross vengeful actions by arrogant aristocrats are today thought to have characterized the upper classes of 18th century France.

The central cast from Leconte’s Ridicule

I should say the parts of the film she managed to show (a startling scene of one young man pissing into the lap of a crippled older one) were meant to shock us, and I was fascinated by the use of masquerade in the film (as I found a similar use of the motif in Clarissa 1991: to show a rank and vicious world). Prof Fink seemed as mesmerized by Fanny Ardant (who played Mary of Guise in the recent Elizabeth movies starring Cate Blanchett) as Prof Reichek said we were intended to be Asia Argento as Vellini (see below).

The second session run by Prof O’Neill (also same title as above, with a “II,” Sat, 9:45-11:15 am) was one of the best sessions I attended in the conference. I was charmed by the first paper, by Bonita Billman, because it was about the 1945 Paramount movie, Kitty, directed by Mitchell Leisen, based on a romance by Rosamond Marshall, starring Paulette Goddard, with Cecil Kellaway as Gainsborough. The third speaker, Raymond J. Ricketts, who spoke about Tony Richardson’s 1963 Tom Jones said it was this film which inspired him to want to study the 18th century. I raised my hand after the papers were over to say that while Kitty, the film didn’t inspire me to study the 18th century, it was my first encounter with the period. I was 8 and saw the movie on Channel 9. I remembered the 18th century as particularly alluring and romantic ever after, and that I still remembered a book of black-and-white stills which I treasured. At this Prof Billman produced a copy of such this book.

Prof Billman was concerned to show us how Leisen worked to make the details of his film historically accurate. The story line is that of Pygmalion with first Gainsborough and then Ray Milland as Sir Hugh Marcy (rhymes with Darcy) teach the street waif and potential prostitute to be a model and then grand lady.

Paulette Goddard as Kitty getting into costume

The clothes and postures of Goddard were modelled on actual paintings of the era (not all by Gainsborough), Gainsborough’s real studio evoked, with an attempt at replications of real buildings. I suggested afterwards that Pam Cook and Sue Harper have argued that the popular film usually eschewed historical accuracy in order not to intimidate the audiences and also allow their imagination to run free (as central to the point of popular films is erotic release, dream-like wish-fulfillment adventures). Prof Billman agreed and said Leisen was unusual in his interest in the historical period of the film.

Apparently the film is not available as a DVD; it is one of 700 films locked up in a disagreement between Paramount and Universal.

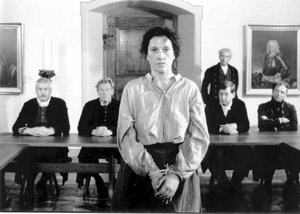

I had trouble understanding some of Waltraud Maierofer’s paper on Anne Goldin, lezte Hexe (translation: the last witch) as she was a German speaker and I knew nothing before I cam in about the hideous torture and unjust cruel execution of this woman in Germany. Golden was accused of infanticide, & was the victim of a power struggle between two families.

Cornelia Kempers as Anna Goldin on trial

The movie was written and directed by Gertrud Pinkus, based on a famous novel by Eveline Hasler, and it emphasizes how the process of writing down what was said as well as coercing terrified false self-accusation made this woman seem guilty. In the movie and book, the records are shown to have been heavily manipulated, with the woman’s own dialect words never quoted; her direct speech is erased and substituted for it middle class distanced generalizations. (Danielle Ofri shows in her Singular Intimacies shows this is something one sees in medical records and examinations at mortality & morbidity reviews in hospitals. ) Prof Waierofer said the movie showed the importance of words, and is part of a new historicism in movies whereby movies tell history more or as effectively as verbal narratives. She suggested that the film leaves the viewer wondering if truth ever comes out of court room and deposition statements. The novel had apparently made extensive use of original documents.

Prof Waierofer seemed not to want to get into the issue of infanticide, though she acknowledged there is a long history of blaming women for the death of infants and when the woman is powerless murdering her if she is unmarried and cannot prove herself innocent. Anna Goldin was a servant who wanted desperately to keep her job. Prof Waierofer then went on to say a child’s testimony (upper class) was believed over that of Anna, and Anna was forced to say she was not harassed by a woman who had pressured her and is said to have left a bad impression on the public when she tried to tell the truth of how this upper class family had treated her. (So much for the idealism and romance of Richardson’s Pamela.)

The paper by Raymond Ricketts on Tony Richardson’s Tom Jones, screenplay by John Osborne, was on an important topic hard to and hardly ever talked about in detail, partly because many film studies people may not know enough about music: he wanted to show us that although this film has been much praised for its translation of Fielding’s book and counter-establishment culture subversion, it continually uses music in ways that lead the audience to have conventional complacent responses to what’s going on. He showed us the overweaning lavish score was a compound of elaborately orchestrated mid-20th century music practice with quotations from harpischords and recognizably 18th century sounds. He argued (rightly) scores produce, reinforce and alter mood, provide interpretation of what we are seeing and hearing, establish continuity from scene to scene. He played pieces slowly so we could hear the modern piano playing inbetween the 18th century instruments. Martin Battestin may argue the movie is comic and witty and distanced, but looking at the music, we find it’s nostalgic, and gratingly or simplifyingly pointed (e.g., using intertitles when the baby Tom is born to distance and entrance us).

So to take specific instances, Prof Ricketts revealed how the famous long tracking hunt where there is no music only apparently realistic sounds of a hunt ends in a sequence of highly romantic music where Tom (Albert Finney) saves Sophia (Susannah York); how comedic music is used to make us dismiss the over-sexualized Molly (he said her leitmotif was a “sexy slut” theme):

Tom and Molly Seagrim (Diane Cilento)

The women are presented as pursuing sex with the man: Lady Bellaston is introduced by a saxophone, while Sophie is accompanied by sweet tunes, sounds of birds. He said scholarship on film must start to deal directly with music. In Brave Heart the ullian harps were important; in Frears’ and Hampton’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses Handelian music was used to powerul effect.

When he finished, I was wishing I had said more about the anamnesic music in Clarissa which I think is central to its gothicism, but myself didn’t know enough about what I was listening to beyond that the harpischord was being used in odd modern percussive ways. I also was proud and glad I had participated in Prof O’Neil’s panels.

Prof Guy Spielmann was panel chair for an earlier session on film, “Envisioning the Eighteenth-Century through—or against—film, I” (Thurs, 11:30-1:00 pm). The first paper by Dorothee Polanz was on De Sade movies and at least informative. She said De Sade films are 1) presented as film adaptations of his books, and are erotic fantasies; are 2) biographies where much liberty is taken with the factual record; or 3) depict him as a kind of horror, a monster, often with dark magical powers, likening him to figures like Dracula. Very few of De Sade’s works have really been adapted (in the 60s 7 films); 15 focus on his biography, mostly his later life and these explore issues of sexual censorship. She showed some awful movies, grade Z (The Whip), where the level of understanding or audience aimed at was like that of Jason and the Argonauts (famously imbecilic); of interest to me was the actors playing ordinary people in one of these films were meant to be taken as Americans, and the woman was presented as sickened and disgusted by De Sade while the man disdained him. I wondered if the real subject of these awful films was a stereotypical idea about American audiences and puritanism.

The second paper was superb: Bradley S. Reichek talked about Catherine Breillat’s Une vieille maistresse (2007), which I saw with Yvette earlier this year. The movie is an apparently faithful adaptation which uses intertitles to situate the viewer in an earlier time than 1830, specifically we feel we are in the time of LaClos’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses. The novel by Jules-Amedee Barbey d’Aurevilly was written in 1830 and hovers between the two eras, with the hero as a weak & amoral dandy. Prof Reichek went over details in the film to show how they translated the book effectively, and from a feminist standpoint. For Breillat female sexuality is fatal forcem and the aristocratic world of the 18th century decadent. What I thought interesting was the idea that the 19th century novelist and 20th century audience regards the 18th century as an era when put on film as a place to examine and explore (break taboos over) sexuality in contemporary life. I think this is true of the 1991 Clarissa. He also suggested this film shows us a certain vision of the 18th century as an amoral time, where scandal was hypocritical gossip and people interacted performatively and with wit.

Nonetheless, the theme of the actual novel, a man conflicted between choosing a highly sexualized devouring and amoral woman, and a chaste, innocent, wife to live respectably with is a theme found in 19th century novels. Our hero is torn between a dangerous passion and a quiet safe life. This reminded me of many of Trollope’s males in his novels. The film had a number of powerful women, beyond Vellini, for example, the wife’s grandmother. It was a kind of replay of Les Liaisons Dangereuses with different characters in place of Madame de Merteuil and Tourville. Asia Argento who played Vellini has elsewhere done highly sexualized women.

One of the chaster pictures of love-making in Une vieille maistresse. Ryno, the seduced hero (Fu’ad ait Aattou) has just been shot and we have witnessed close up the ghastly pulling out of a bullet from his body, and Vellini (Asia Argento) is allured by him because of his pain and the blood

We did in the discussion afterwards talk about films set in the 19th century and based on 19th century books. The consensus was films adapted from 19th century matter, history and themes can deal with sexuality then and now, but often this becomes implicit or is a matter of intense repression (another theme then). Instead such films tend to deal with class, social and economic arrangements, and particularly males and females struggling for dominance over one another. Someone decided that the Austen films were a “class apart,” but I didn’t get a chance to ask him why he said that. It is true that Austen films are ostensibly set in the later 18th/early 19th century and yet present a repressed and often very conservative vision of women’s sexuality (so belong to 19th century films so to speak). The remark did cheer and give me pause because one of the thoughts I want to develop in my book (to be begun this summer) is that the Austen films do constitute a subgenre of women’s films or costume drama & film adaptation apart, different, distinguishable from all others.

It had taken Prof Spielmann and his technical assistants over half a hour to get the equipment working, so there was little time left at the end for the third paper. Perhaps this was why the French scholar who had written it gave it in French reading at top speed, looking down at his paper. It was on Marie Antoinette so this was disappointing for me.

I missed another paper which may have been a brilliant and even important paper: I did not make it to the second of Prof Spielmann’s panels (same title, with with a “II,” Thurs, 2:30-4:00 pm), and thus didn’t hear Robert Mayer (who is the editor of a volume of good film studies, Eighteenth Century on Screen). Prof Mayer spoke “Three Queens, the Eighteenth Century in Classical Hollywood Cinema.” I had gone to hear Mary Trouille’s paper on law and custom in marriage in France, and since there were so few people in the room didn’t have the nerve to scoot out after she finished. I should have. There followed two graduate student papers, one of which was silly (about how one should pity Willoughby in Sense and Sensibility); earlier I had scooted out from a crowded Clarissa session to hear a paper that wasn’t worth it after all, and then found I had no seat when I returned so I did stay. It’s so difficult to guess what is best to do. I am learning that not only are the sessions with respected or “big” people crowded because they are semi-stars, but because often such experienced people do give better papers.

One of the themes of Mayer’s paper (told me by hearsay, i.e., someone who was there) was one found in all the papers Prof Spielmann chose: what do these films tell us about our ideas of the 18th century & their queens, & how do these reflect our own concerns today. In the first session run by Guy Spielman two of the speakers brought out how not only films about Antoinette but modern historical fiction and good or intelligent biographies about her & other famous 18th century figures are really dramatized modern depictions of sexuality, sometimes heterosexual (Zweig for example), sometimes more lesbian covertly (e.g., Chantal Thomas’s Adieux a la Reine).

Petit Trianon in Marie Antoinette’s garden

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Fran:

“I’ve not actually read anything by Eveline Hasler, though her historical books have been recommended to me before, but the Anna Goeldi case is an especially well known one over here, what with Switzerland’s proximity and the case being the last of its kind in Europe.

It was also very much in the news again last year, since a new book on the subject by Walter Hauser in 2007 and the new campaign associated with it led to the Canton of Glarus finally exonerating Goeldi of any crime and declaring the case an abuse of justice.

Since you mention not following everything in the talk, I thought I’d add a few details gleaned from the press and other German sources, which might help make the connections.

You mention Goeldi being accused of infanticide, but I don’t think that was ever really the case. The closest she came to it was probably when her first illegitimate child was stillborn. She was working at a vicarage at the time and kept the pregnancy hidden to keep her job and so had no medical assistance at the birth – she was pilloried for her wanton behaviour, while the father who had left her in the lurch, Jakob Rhodener, seems to have got off scot-free.

She’s also known to have had a second illegitimate child later with an employer, Dr Zwicki, though the pregnancy itself had again been concealed and nobody actually knows what became of that child. Zwicki himself must have felt some sense of obligation to her at least because he tried to help her when she got into that fatal conflict with the Tschudi family: he warned her of her approaching arrest, so she could flee, but she was apprehended after a concerted search action, which incuded wanted notices in the most prominent Swiss newspapers like Zurich’s still existant and respected NZZ. As your speaker probably pointed out, practically none of these newspapers carried the story of her trial and execution in the subsequent censorship clamp-down.

In fact, the details only became widely known because two German newspapermen, Ludwig Wekhrlin and Heinrich Lehmann, were present at the trial and managed to get away across the border with incriminating evidence of its irregularities before they could be apprehended themselves. They subsequently published highly critical articles which led to wide European outcry.

Lehmann in particular had been given secret minutes of the court’s proceedings by the court’s secretary, Johann Kubli, who, though against the death sentence himself, had been forced to write up the court’s findings and ostensible reasons. Lehmann had kept his source secret, but Hauser apparently found the name in papers still in the Lehmann family’s possession.

‘Ostensible’ seems the right word to use, given the circumstances. Anna Goeldi accused her employer, Dr Johann Jakob Tschudi-Elmer, of making improper sexual advances to her in 1781, a potential scandal that would have put an end to his budding political and judicial career in ultra-conservative Glarus. It probably wasn’t exactly politic to make those accusations to his relative, Johann Jakob Tschudi, the all-powerful head of the Protestant community in Glarus.

The same year she had a run-in with her employer’s spoilt and wilful child, Anna-Maria, who promptly started spitting nails, throwing fits, and manifesting symptoms of paralysis and then claimed that she’d seen Anna and her older friend, Rudolf Steinmüller, in her room under circumstances suggesting witchcraft and been given a bewitched sweet that had led to the symptoms.

Tschudi cried witch, his relative manipulated things so that his own Protestant court was put in charge of the case, although as a non-native Anna should have been tried by the bi-partite, Common Council instead, which the Tschudis didn’t control, and they had her tortured her into confession that she had been in league with the devil, although there was no legal basis for a witch trial according to Glarus laws in the 18th century.

That’s the reason why they had to fiddle the court protocols and change the charge to attempted poisoning, but that charge carried no death penalty when there was no fatality, so the sentence itself was still invalid. Anna Maria had miraculously recovered after Anna Goeldi had been forced to lay hands on her and ‘cure’ her – which cure of course then ‘proved’ that she was a witch in the first place. To top every thing else, the doctor monitoring Anna Maria’s case and called as a medical expert in the trial, Johannes Marti, had studied medicine together with her father and was an old family friend.

Anna Goeldi herself was allowed little or no legal representation until just before the (already determined?) end.

Her accusations against Dr Tschudi-Elmer were amongst the case documents conveniently lost in the archives.

People tend to forget Rudolf Steinmüller, but he was a victim, too. He held out longer, but he was an old man subjected to considerable duress, constant questioning and incarceration, if not quite the same brutality, since he was not without important relatives the Tschudis had to consider (unlike Anna Goeldi), and he finally broke down and confessed himself when Anna Goeldi was tortured into denouncing him. He subsequently committed suicide in his cell.

These evil-minded or opportunistic girls keep popping up quite a bit – ‘’The Piano’, ‘The Children’s Hour’, ‘’Atonement’ etc. and now presumably in this real-life tragedy, too.

Fran”

— Elinor Apr 13, 3:15pm # - Thank you very very much, Fran. I see I did misunderstand and missed a great deal of what was said. The speaker assumed I knew more than I did.

She began with how many people in the “enlightenment” era by the time of Goldin (Goeldi’s life) were priding themselves upon having freed themselves from barbaric superstitutions. She didn’t say this but her talk showed that many had not, and that even those who had used such superstitutions to shore up their power and destroy the weak and vulnerable. Not very different from today.

I did not pick up the stories of her love life before coming to work for Tschudi-Elmer. I did pick up it was Pamela story which told the truth: such pressures from male employers usually destroyed the woman servant in one way or another: she gave in, got pregnant and was fired; or she didn’t give in and was fired; in either case, her reputation was besmirched and she didn’t get good references.

The speaker did keep coming back to the young girl spitting nails. Fran is right that we keep coming across these small evil girls. Right away as I read Fran’s words I thought of the famous terrifying 1950s US popular novel, The Bad Seed, written by a woman. In The Chlidren’s Hour I was bothered my making that young girl the evil source of the misery for all, not society at large. When boys are presented as bad, usually they are not malicious in quite the same hypocritical insidious way but rather coarse crass bullies, and thus not as frightening. This evil young girl pattern is not one I had been noticing, but yes it’s there in women’s plays and novels.

It does make me feel better about McEwan’s Atonement because I feel he means to make us see also how natural it was for Briony to suspect, be frightened, resentful, and that she was overpunished, over blamed—for the most part his book exonerates males from harshly aggressive sexual violence towards females; he seems to feel bad for Lovelace (Robbie stands in for the part in the rewritten paradigm). McEwan means to imitate Virginia Woolf; he participated in the movie and in the movie we have shots of old women pushing carts home from the supermarket, as landladies, as the deserted housekeeper mother of Robbie, suggesting to me McEwan read Woolf at a deep level, for such images recut in her writing over and over again. In other words, he’s a man deliberately also writing a kind of woman’s novel.

Ellen

— Elinor Apr 14, 1:04am # - From Fran:

”’She began with how many people in the “enlightenment” era by the time of Goldin (Goeldi’s life) were priding themselves upon having freed themselves from barbaric superstitutions. She didn’t say this but her talk showed that many had not, and that even those who had used

such superstitutions to shore up their power and destroy the weak and vulnerable. Not very different from today.’

That was also one of the main reasons for the attempted and almost successful state cover-up in Glarus. It wasn’t only to protect the Tchudis: the Cantonal authorities were deeply embarrassed to appear so backward, superstitious and unenlightened in the eyes of Enlightenment Europe and did in fact no longer have any laws sustaining such witch trials, as I mentioned.

Like many of the other inner-Swiss cantons, however, Glarus is still a pretty conservative place, one of the strongholds of the populist SVP party and its message of Switzerland for the (preferably white) Swiss and its ruthless attempts to exclude anything ‘other’. They were actually the party, too, who voted against Goeldi’s rehabilitation – as you say, not so different from today:)

Fran”

— Elinor Apr 14, 9:12am # - Dear Fran and all,

When I was working on my project for putting up an etext of Caroline de Lichtfield by Isabelle de Montolieu, I did a good deal of reading about Switzerland—where she lived. I found that although there was a claim to great enlightenment and liberality, while certainly the state apparatus was freer than in France (for publications say), when it came down to property, power to particular family groups, and what goes by the name of stability (keepings things as they are), the punishment for rebellions was as draconian, the agents is place as vigilant and ruthless, and a number of incidents of suppression showed at heart the ancien regime was as thoroughly in place as anywhere else. There were ameliorations, mostly in the cultural arena, particularly for intellectual and upper class types. There was less nightmare severity over religion too—this because the country was protestant and grew out of a kind of toleration for three distinct groups.

All this can be varoiusly seen in De Stael’s life story, and that of Madame de Charriere and the Constants (Benjamin, Rosalie). Madame de Genlis did find a haven there and other French aristocrats—but we should see who is being saved; and that they are doing it on their own money and connections.

Ellen

— Elinor Apr 14, 9:20am # - From Nick:

“The blog is terrific. More films for the TBW list (I am compiling a To Be Watched list to go with my TBR list – just listomania I suppose).

Nick.”

— Elinor Apr 15, 12:11pm # - In my blog I described how similar Joe Wright's 2005 P&P and Atonement are, and how the talk on the 2005 P&P shed light on the film Atonement and vice versa. Well, I bought Hampton's screenplay for Atonement. I learned just about all the important people in the tech and production crew for P&P were in Atonement; Keira Knightley was not the only repeat. James McAvoy played Tom Lefroy in the awful Becoming Jane too. One might say Wright’s Atonement is an honorary Austen film: especially if you consider McEwan alludes centrally to Northanger Abbey in it, and McEwan was in on the writing and producing throughout.

Joe Wright said he was thinking of Brief Encounter and Rebecca (1939 version) when he made this film. it is a piece of intense romance, about the love that never happened, never came off -- which is again, a theme one finds in the Austen films, e.g., 1981 film of Sense and Sensibility for Willoughby and Marianne. Since the photography is spectacularly lush and the production design high costume romance, while Brief Encounter is associated with all that is drab and sober in look, I thought this colloquy revealing.

Within the movie, in a dream-sequence Robbie passes before a large screen on which Le Quai des Brumes (1938, Jean Gabin, Michele Morgan) are kissing and talking. This is said to be an example of "French poetic realism;" it's described as "hauntingly sad, quietly emotional," & the story line is parallel to that of Atonement. A young man, an army deserter, flees, falls in love in a small town, tries to create a new life with her; they are killed. Another one on longing for impossible happiness and the reality of loneliness. Wright is also thinking of movies of WW1 and 2 -- like In Which We Serve.

. Ellen

— Elinor Apr 15, 1:04pm # - I thought people might be interested to know there has been a French mini-series film adaptation of a Radcliffe novel. You’d think there’d have been many films as she's so pictorial, with incidents providing lots of room for sex, violence, & landscape. None in English—fearful of it I expect, too sexy, or perhaps it's (contradictorily) that Radcliffe's reputation is ironically (?) that of a prude and prissy. Radcliffe has been more deeply appreciated among a continual popular readership in French and Italian (there’s a modern translation in Italian of Udolpho, a very good one):

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0220213/

Le Confessions des penitents noirs directed by Alain Boudet, screenplay Marcel Moussey, 1977

Ellen

— Elinor Apr 19, 9:02am #

commenting closed for this article