Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Movies at the MLA · 7 January 07

Dear Harriet,

The second set of papers I heard & read which I want to describe are those on film. They were alluring because just about every speaker brought along fascinating clips. I went to "Homecoming Narratives in the post-WW2 Cinema;" in a session on Terror, someone gave a paper on a Polish film, Kieslowski’s A Short Film about Killing, and I got to a session which examined film adaptations of non-fiction and fiction stories, "Television and Film Narratives." All but one of the eight papers included chilling seemingly accurate photographic footage of unnerving & uncanny experiences.

The key to films about coming home after World War 2 is the full trauma, horror, and meaninglessness of what has occurred is presented indirectly. Many of the films appear to be about gangsters, and armed conflicts at home. In "The Enigma of Return," Elisabeth Eve Bronfen described and screened clips from Key Largo, Thieves Highway and The Long Night. I could hardly believe such jejeune assertions of pious patriotism ("it’s better to die than live a coward"); the nostalgic reunion is longed for, even with a replacement male, but what the veteran experiences is dislocation, a sense of the impossibility of psychic adjustment: the once familiar world is now unfamiliar and depressing, irrelevant. Bronfen had one clip of Henry Fonda inside a room with many windows; from outside he is bombed, shot at, under continual horrifically noisy assault.

In her "When the Women Returns," Isabel Capeloa Gil suggested few films have a revenant female, and, when there is one, she must be punished and is partly a femme fatale. In I’ll be Seeing You, Ginger Rogers is a woman prisoner who has murdered someone, allowed to leave prison for a while; Robert Mitchum, a traumatized Vet who falls in love with her. Women are not allowed to be re-empowered centers of home life; she is a refuge, a displaced person, is when she has experienced war somehow forever a partial or complete outcast.

I was really startled by the films screened by Christiane Schonfeld in "Coming Home in Germany:" not only the footage of the devastated bombed Munich spoke of the horrors and deaths and absences, the home itself becomes the target of ferocious attack. Spectral scenes of death and abjection alternate with bleak assertions of national identity in film noir.

I asked them to discuss the 1989 film adaptation of Bobbie Ann Mason’s In Country by Norman Jewison where Emmet Smith is slowly reintegrated with his family in Kentucky. There is a gay subtext as he does not become involved with woman as his lover; the girl in this film is his niece, Samantha Hughes who goes with him to the Vietnam Memorial. They suggested such a film was allowed to be much franker and thus was less neurotic as an art product. I have twice assigned Mason’s novel to my classes, and twice screened the movie. It’s written from Samantha’s point of view in the way of Jane Austen’s Emma: we have to see beyond what Samantha sees as we watch her learn about war and begin to mature.

I won’t soon forget Esther Raskin’s "Inscriptions of Terror: Kieslowski’s A Short Film About Killing. She described and played parts of a 1988 Polish film where a young man brutally and at great length (making the man suffer) murders a cab driver; the film closes with a similarly long sequence showing the barbarity with which the young man was hanged. She said the film inquired into the motivations of killing. The film opens on a group of young boys hanging a cat; we see the young man early on throwing stones into traffic in order to cause horrible accidents. Apparently there had been such a young man, and she wanted us to believe the acts of killing can be understood as the acts of a young man whose sister was killed in a car accident, a sister who was the only one in his family to love him. She seemed to care more about her theory of the horribleness of this young man’s cold family than the horrific brutality of his killing.

Less chilling photographic imagery was dwelt upon in "Television and Film Narratives." Still when the pictures were documents of real and shocking events the resultant film became powerful. Marc Singer discussed how Oliver Stone’s films about the Kennedy assasination, Nixon, the World Trade Center were arranged to produce mythic archetypes (mostly conservative) and push Stone’s particular explanation for the events in question. These films reveal the interplay of history with popular memory and desire. A retrospective structure characterizes, insertions of narrations within narrations (through flashbacks) characterize Stone’s films.

Eckart Voigts-Virchow showed how in DVDs the reader buys paratexts, framing features, Genette-like epitracks, and over-voice which provide for the most part bogus explanations for the movie, and when played with the movie distance us. He played one such feature where the company was clearly mocking the new "bonus" material offered in such packages. "Cinephilia turns into technophilia."

Jessika Thomas showed how in the 1995 several part BBC Moll Flanders Defoe’s book which is confessional, about money, and does critique the society which Moll survives in is turned into erotic romance. The script by Andrew Davies opens with the sexual abuse and neglect of Moll as a child; the film omits her prostitution, marriage to a man in Bath and 3 children by him; her affair with her brother. It keeps the main hinge points of the plot-design and when last seen Moll is with her ex-highway man cavalier, Jemmy; both are arriving in the US against a backdrop of gorgeous sea and land scenery. The film though shows that by suffering you can triumph in love and marriage. Alex Kingston, a beautiful actress who played Moll, makes herself into a commodity for men. Davies did preserve Moll as narrator (through voice over) and sly accomplice of the audience (as Fanny Price was in Rozema’s 1999 MP). His dialogue encourages us to imagine ourselves asking, "What could you do were you in her situation?" Russell Baker’s introductions provided background which suggested Defoe had the sociological aim of investigating the injust degradation of women. Moll sticks by society’s code; uses what’s available, and she is in the end rewarded. The moderator of the panel, a British woman, said when the film played on British TV it was also introduced with advertisements for the supposed civic-minded bank which funded it; and each week it played it was preceded by cartoon movies showing people hurrying home, cooking their supper, and sitting down quickly in the front room to watch the show together, thus underpinning its function as group entertainment in the home.

A separate paper someone sent me from a Victorian session had this to say about Andrew Davies’ film adaptation in general (with eerie clips from his 2001 adaptation of Trollope’s The Way We Live Now in particular): across all the novels he adapts, his scripts show a detached, sympathetic irony towards the more sentimental or melodramatic characters; shows great sympathy towards the amoral and less than admirable protagonists and use these to reflect on the cruelties and double standards of the world which judges them; is usually amused and amusing (lightens when he can a text); adds literal action wherever possible, and tries to take advantage of particular actor’s strengths.

The only place I’d disagree with this is in the 1999 BBC adaptation of Elizabeth Gaskell’s Wives and Daughters where I thought there was much less distance and an intense emotionalism which was moving and appropriate to the subplot (the Hamleys). I’d also say Davies consistently substitutes a masculinist outlook on women’s texts so that what emerges each time is the centrality and necessity of romance and marriage for the woman characters and betrayal of women by women when in the original novel other patterns of life and paradigms and communities of women are as important.

Yes I know that popular journalism says Davies adds sex. Maybe, but he usually takes the sex he adds from real hints and things going on oftstage in the novels themselves. And he is as comic often as he is dark and sombre.

I asked Jessica Thomas and Eckart Voigts-Virchow could they discuss what would be the different effect in watching the same film without the paratexts of the DVDs or the framing narrator, cartoons or commercials of TV. Basically when such films come without these additions, when the original place where the episode ended is obscured because all the episodes are run together, the effect of the film is changed strongly. Without Russell Baker, and with the episodes run together, the 1996 BBC Moll Flanders is sheer idealized romance, a love story where marriage is not a commercial arrangement, but an exciting adventure acted out of the passionate impulses of body and heart.

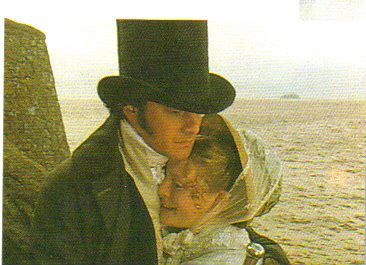

Professor Virchow’s comments after he read his paper were the most interesting about film. The new technologies enable viewers to distance ourselves from the stories and characters of films and even when they are bogus demystify the product. I know that my many featured DVD of the 1995 BBC P&P (scripted by Andrew Davies) has changed my outlook on the film because I am able to watch sequences very slowly and really pay attention to its high romance and careful setting out of archetypal wild scenery, psychological stereotypes:

Darcy (Colin Firth) grim, rescued almost betrayed sister Georgiana (Emilia Fox) by rock over the sea

Tomorrow night I’ll connect the above to a book and essays about costume dramas I’ve been reading.

Elinor

P. S. Marianne, today it was so summery in my area a small cherry blossom tree bloomed in a nearby neighbor’s lawn.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- P.S. I placed on WWTTA, ECW and Trollope-l, the following casual review of the film adaptation of Zoe Heller’s Notes on a Scandal:

Dear all,

More on a film adaptation of a respected novel, this one 20th century:

Although directed by Richard Eyre and written by Patrick Marber, this remarkable movie is based on a book by a woman, Zoe Heller, and also focuses on women’s lives—with a real attempt at getting at the reality of these as felt by two of the women characters: Barbara Covett (Judi Dench) is an aging intensely lonely spinster; she clearly has lesbian leanings but cannot act them out from her own repressive background and because of the reaction she seems to have gotten from all the women she’s approached: revulsion. This is a movie which doesn’t quite believe there is much lesbianism in the world and treats it as abnormal in ways that say Capote did not treat male homosexuality. The film is deeply sympathetic in many ways to Barbara, but it’s hard if you are in the audience to keep this in mind as the audience (the one I was in) actually hooted and jeered at moments, laughed: they refused to take Barbara’s state of mind seriously (by comparison Capote’s was).

The other is Sheba Hart (Cate Blanchett) who is lured into an affair with a 15 year old; she seems to be presented as woman as flotsam and jetsam; there is much class analysis in the film and she is presented adversely as a typical upper class English woman who can’t take care of herself and falls into bed with whomever; she is presented as beautiful too and thus her present husband, Richard Hart (Bill Nighy) married her at 20 after leaving his wife and 3 children.

Alas one interpretation here could be "what comes around:" he is enraged when he discovers she’s having an affair with a 15 year old; she wants to know how that was different from his affair with her. He is much older than she and the average audience goer could take another bigoted reading away": see what happens when you marry someone so much older than you.

Yet despite this surface of encouragement of bigotry, narrowminded, and dismissal of women, the film is actually worth seeing for the strong subtext which I think works in the opposite direction. We see the loneliness and real dignity and respect of Barbara’s life. Sheba is given no opportunity to live a life of her own (she was unlucky enough to have a Downs’ syndrome boy who has taken 10 years of her life and continues to require continual care).

I think at one time it was impossible for a movie really to present the hardness of people to one another the way it’s seen in this film when the scandal breaks out; how the pettiest of bitternesses is what drives people’s behavior; the stupid physical violence of the boy’s mother at Sheba for example. I wrote about The Light in the Piazza on my blog and here, and really think the two media spectacles (both aimed at mass audiences) shows that indeed we have made some progress in openly showing reality of women’s lives since the 1950s.

I don’t know if this is a recommendation to see the film in the theatres. Maybe rent the DVD when it comes out so you can see it in quiet peace. It made me want to read the novel. Strong performances by all three principles (Dench, Blanchett and Nighy)

E.M.

— Sylvia Jan 7, 10:32pm # - When Fran answered me, she now would like to read the novel she’s had out from the library, I answered as follows:

IN response to Fran,

Yes. I cannot but think that the presentation of Barbara was very different in the novel—much much more inward. Also that some more interiority was given Sheba so we’d understand her better too. The title is after all: What Was She Thinking: Notes on a Scandal.

On the summary of movies I wrote last night for my blog, I wondered if you’d seen the scary film A Short Film about Killing. I was really bothered not by how the woman argued that in fact the film might not have been meant to anti-capital punishment and meant to suggest ways in which we can understand why the young man did such a horrible deed, but how her language made it explicit that somewhere in her mind she thought her idea his mother and siblings hadn’t loved him sufficiently was more "horrible" than the brutal murders he committed.

The session on "returning home" movies made in the middle to later 1940s seemed to suggest there were a number of real masterpieces at the time neglected then and now partly because they were and still are framed as commercial unintellectual (and thus low-brow, silly) films in order to make sure they would not intimidate people from going.

E.

— Sylvia Jan 7, 10:34pm # - Fran wrote:

"I’m sorry, but no. Even as a long time crime and mystery fan, though, I would agree that there is often a tendency to marginalize the victim and the brutality of the crime in respect of understanding what help form the killer’s personality and furnish the motives. Perhaps it’s this marginalization, however, that makes any enjoyment of the story possible.

You mentioned attending Elisabeth Bronfen’s talk. Her own courses in Zurich this year revolve pretty much around violent themes, one takes the use of blood as an image, citing films such as Kill Bill, another deals with the American Gothic in book and film, citing people such as Kubrick and King.

It’s interesting the subject should come up today since my husband, who is not a fan, actually watched a TV crime film with me last night and quite enjoyed it since the detectives were a fairly decent bunch of quirky German actors, but said afterwards his basic problem with this stuff is that it often takes violence as its starting point, and he’s always left with the feeling it shouldn’t be celebrated in this way.

Fran"

— Sylvia Jan 7, 10:35pm # - Judy wrote:

"Re Notes on a Scandal – this was the full original title when the book was first published in the UK. The extra line ‘What was she thinking?’ was added for the US edition. I’m not sure why, but I think I’ve read somewhere that it was to make it clear it was a novel rather than non-fiction. (I don’t know whether Zoe Heller came up with both titles, or whether a US publisher added What was she thinking?)

I mainly liked the novel although some aspects didn’t seem very realistic, and in particular I liked Barbara as unreliable narrator, trying to hold everything back but revealing a great deal about herself despite all her efforts. I was interested to hear Ellen’s thoughts on the movie, and will look forward to seeing it when it is eventually released in Britain."

— Sylvia Jan 7, 10:37pm # - I was delighted to discover that Heller produced an edition of Austen’s Lesley Castle. At first I thought Heller wrote a sequel, but no, it’s an edition.

Lesley Castle is one of Austen’s more interesting juvenilia; it has a character named Eloisa based on Rousseau's Julie, and some striking alienated and melancholy comments coming straight out of the author’sconsciousness. I have found myself repeatedly returning to this text to reread this or that remark to give me courage and validation.

I should say Lesley Castle is epistolary and has several voices: one is hilariously funny; an "old maid" type who does the work of a wedding and whose sole idea in life is getting everyone to eat all the food they absurdly prepare.

Thank you to Judy for setting us straight on the titles. A few weeks ago someone wrote me about a paper he wrote about how to find poetry. He argued in the paper that titles change constantly, but not the first lines of poems so in finding a poem you should look to the first line.

Publishers seem to think that because the title and cover of a book are what sells it, they have the right just to change the title as often as they change the book’s cover and that anything goes for the cover which will sell the book. Glendinning says Leonard Woolf agreed to be a long-time editor and contributor to a couple of important periodicals (the New Statesman among them) because he was promised he would never find his name put to anything he had not written. It would appall me to see my name put on a cover I loathe. Titles count even more. They are not just selling devices.

I agree with you and your husband, Fran, that these films which purport to, and maybe do explore and critique brutal violence, also end up celebrating it. This is in the nature of photography. The very art becomes poisoned at the source because of the human reaction to it. Woolf wrote an essay where she declared movies were a savage art, one which drew on the atavistic self in all of us.

E.M.

— Sylvia Jan 7, 10:45pm # - From Howard G:

"Ellen forgot to mention how extraordinarily delicious Judi Dench’s performance is! One of the all-time great film performances. And Cate Blanchett holds her own—as does the rest of the cast, for that matter.

Howard"

— Sylvia Jan 8, 8:08am # - Dear Howard,

Dench also gave a magnificent (truly poignant) performance in Ladies in Lavender: there she was a woman in her sixties yearning to go to bed with a young man in his twenties; the sequences included her dreaming of having sex with him. Very daring and she did it with aplomb and taste. She’s underrated because often she’s not given good parts (or given cliched ones).

Yes Blanchett holds her own.

So too Nighy. He’s not there much, but when he is his character is perfectly real, absolutely persuasive (though I think now he is presented almost without criticism while the other two are presented for us to criticize or feel alienated from).

E.M.

— Sylvia Jan 8, 8:22am # - From another blog, Roxie’s World:

http://roxies-world.blogspot.com/2007/01/notes-on-stereotype.html

Her argument in a nutshell is accurate: the film displays everywhere "trope of the predatory repressed lesbian;" in addition, Sheba (Queen w/o brains) is available to anyone, no agency whatsoever.

I do disagree last year’s films showed such sympathy for homosexuals or transvestites. I would argue that Brokeback Mountain presented gay men as sick

and miserable, and TransAmerica made flexible sexuality into a nightmare which breaks up the safe needed families. The only sex shown in Brokeback Mountain was between one of the men and his wife. I wrote about TransAmerica on this blog.

E.M.

— Sylvia Jan 9, 9:17am #

commenting closed for this article