Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

ASECS, Atlanta: The marriage act of 1753 · 3 May 07

Dear Harriet,

On the last day of the recent American 18th century society meeting at Atlanta, I attended a session on Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act of 1753. It was the most informative session I attended; all the papers seemed uniformly filled with information and perceptive insight into the texts analysed, and the discussion afterwards was stimulating and content-rich.

First up was Megan Hiatt whose talk, “Parental Consent or Parental Control,” was intended to correct misrepresentations of the Marriage Act’s way of functioning and aims.

Ms. Hiatt began with the parliamentary debate leading to the reading of the bill. Ms. Hiatt thought the act was misrepresented in the debate. For example, on May 14, 1753, it was argued that “our quality by this bill have absolute control over their children.” The person arguing this misunderstood. Ms. Hiatt then read portions of the act and explained these. She said the act did not give any absolute control over children since it literally applied to marriage by license only. (In response to a question afterwards she allowed that bullying of course could easily go on, and the act gave parents a moral handle, a justification for coercion.)

The act (as formulated by Hardwicke and his associates) established a model for family negotiations in which the child was expected to choose a partner first and then go the parents. But more than this was meant (and done) as key sections of it were formulated to prevent clandestine marriages. These were seen as a real problem and for good reasons.

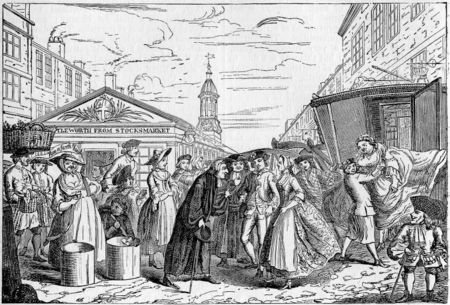

A satiric sketch of one bad result of the state of the complex customs by which marriage could occur before 1753

The act was not meant to obstruct the marriage of a young adult. Ms. Hiatt felt the act rather gave the parent the right to say no to outrageous and romantic schemes. Couples were required to obtain authorization in acts like reading the banns. If the bann was called without opposition three times, then the couple can marry. After that the marriage would be solemnized and registered correctly.

Clergymen were the class of people who might get caught in a struggle between, on the one side, parents and family for control; and, on the other, young adults who wanted to marry without the family’s consent. The way the banns were to be handled shows some awareness of the clergyman’s vulnerable position. (Many clergymen were not rich, or were dependent on their patrons who might be this very family or a possible heir who wanted to marry without consent.) The parents or family could obstruct the marriage of the young adult during the weeks the banns were read aloud; if no protest was registered, then the official performing the ceremony could not be punished.

Ms. Hiatt saw the act as giving the parent a “window” to object. The members of the community were also given an opportunity to object. She said the emphasis was on consultation. By requiring minors to obtain permission, the family and community were attempting to control romance. (So we can see the new move to companionate marriage here.) Ms. Hiatt said the act gave the child the right to say “no.”

I’ll add the question of course would be how much advantage the parent could take and that might be the same before the act so the effect of the act might be a wash. In the later discussion it seemed to be suggested that the act did give more power to the adults in charge and to the community at large and perhaps this was intended. I suggest bullying and intimidation are so central to the way power structures work, that the act might correctly be seen to be part to the “forces” Foucault described as in the 18th century wanting to survey and control sexuality.

Ann Campbell’s was the second talk and she analyzed John Shebbeare’s The Marriage Act, a novel. Let me first tell you about this writer: John Shebbeard (1708-1788), was an apothecary and surgeon who gave up his practice to write. He was an opponent of Addison and Voltaire. His politics were Tory and he also wrote a series of pamphlets, The Letters to the People of England, where he effectively scourged the reigning Whig group; later he did write pamphlets on behalf of George III. According to the Oxford Companion to English Literature, Shebbeare was a pungent and scurrilous pamphleteer, and a bitter opponent of Smollett who caricatured Shebbeare in Sir Launcelot Greaves. Shebbeare wrote two novels, Lydia (1755) and The Marriage Act (1754). What fame Shebbeare has still is owing to this 2nd novel where he presents a wide range of opinions on social issues “haphazardly held together by the character of a ‘noble savage’, an American Indian named Cannessetego.”

Ms. Campbell’s talk was about the politics seething around the act. Most detractors who attacked it did so for political motives; they were sometimes presented as generous defenders of freedom of choice for young adults. Her text was Shebbeare’s The Marriage Act, published one year after the act.

She suggested the subject of Shebbeare’s novel is private and public liberty. In the novel gender and class norms do prove inviolable so the novel is at a basic level reassuring to conventional and propertied readers. The novel insinuates that if you give women freedom to act, they will do badly. Those in the novel who argue against the act, argue you still must give women some freedom. Those in the novel who argue on for the act, say that children (and it is young women who are thought of here) will be married off to villains unless you control them.

An interesting thread in The Marriage Act concerns female elopement, which is presented in opposition to female virtue. In this novel [by an older man remember] a young woman who elopes is doing the very worst and most wicked thing possible. In Shebbearen’s novel even illegitimate prengancy is less offensive than elopement. It seems the great offense is not considering one’s parents and family.

In this novel it is insinuated that the Marriage Act gives the parents power to force children to marry. In reality, said Ms. Campbell (agreeing with Ms. Hiatt) the act did not grant parents authority to force marriage on their children.

Ms. Campbell concluded by suggesting that the widespread opposition to the Marriage Act seems to bolster Laurence Sterne’s idea that companionate marriage was growing as an ideal to be sought.

I’ll add here that again we could apply Foucault’s insight to how people in the 18th century were attempting to control individual freedom in the area of sex. Ms. Campbell’s paper also sheds light on some of Austen’s readers might have responded to Lydia Bennet’s elopement with Wickham in Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, why Mr Collins’s letter is such a vile abomination, and why the whole incident is seen as such a threat to the Bennet family. For a while Elizabeth considers she has lost Darcy forever.

The third speaker, Lisa O’Connell’s paper was “Proper Ceremonies: The Vicar of Wakefield, the Marriage Act, and the Problems of Erastianism.” She contextualized analyzed Goldsmith’s famous novel, written in 1761/2 and published in 1766, in intriguing ways.

She began by talking about the act itself. Abstractly put, the Marriage Act would be an instrument of a Whig administration in power since 1714, and the key would be that such legislation needs to be carefully positioned. Much of the overt resistance to the act came from groups who were like the Tory non-jurors of the early 18th century; marriage is one of the sacred acts. But there were also people seeking companionate marriage though this new arrangement.

The customs of the country before the act are presented as more tolerant and also allowing Catholicism to thrive. The Act required a ceremony or ritual which would be controlled by the state, as by statute it would be decided what marriage was valid and what was not. It specified techniques and protocols. The Act made provisions for the nullification of irregular weddings too. and thus publicly favored Anglican marriage. The punishment for clergymen disobeying these was severe: they could get a sentence of 14 years transportation (an indentured slavery which often led to early death). (I can see how the clergyman becomes a site for pressure and why in novels clergymen would be presented as victims.)

Ms. O’Connell said the act was part of a coherent program of state building. Other features of state aggrandizement insinuated through this law did not get anywhere. But for marriage, it put people in the hands of an oligarchy who would provide control, subordination in exchange for security. The Whig program was generally designed to prevent rebellion, but we see people in government attempting to extend this control to people’s private lives. She quoted someone who said of Fox he had expanded “the great spider of law” into private life.

Basically it worked through the Anglican church and thus supported the Anglican religion. The measure increased its social power at a time when it was a servant of the state. It harnessed the power of the state in parishes as that’s where the ordinary English person felt the state. Clergyman gave sermons which were listened to; the clergyman was to perform the ceremony. The church was the center of communal life, the repository of local memories. It was clergymen whow were supposed to uphold the law.

Many of the mid-century writers were sharply critical of the new regime: Richardson, Fielding, Shebbeare, and Oliver Goldsmith (1728-1744), and Goldsmith wrote his novel from a imagined clergyman’s point of view.

In general, The Vicar of Wakefield is an anti-marriage act novel. Ms. O’Connell said the action and characters of The Vicar of Wakefield supports an establishment Tory politics. It could also be seen as presents a weak Erastianism. The satire on the act and novel paint a bleak picture of society. We have a group of characters who can be seen as allegorizing an argument. There is a libertine squire, a good squire (who supports our hero, the Vicar), the vicar’s daughter is seduced (using wine). This novel shows clergymen losing power. Ms. O’Connell felt Goldsmith’s presence may be found in all the characters in the novel.

Choosing the Wedding Gown, a contemporary illustration for The Vicar of Wakefield by William Mulready

She suggested at its deepest, the novel is a critique of the Marriage Act through the perspective of natural law. People have a natural right to contract marriage; it’s inalienable. The resistance itself is framed in Tory terms, and our Vicar is victimized. Dr Primrose is an unworldly good man, not a state servant; and we see his intimate life become a terrain wherein he and his family may be punished. For him marriage is a mystic occurrence, a fundamental change within. The mode of satire here is sentimental: we watch a victim abused by the powerful people in society; their bases of power is exposed. The Marriage Act is seen as genuinely Erastian.

The novel does end on the fairy tale happiness of romance.

********

Then we had a group discussion where it seems to me many people in the room participated, and many useful questions were asked and informative answers given in reply.

Basically from this part of the session I gathered that the act was meant to stop clandestine marriages, and to regularize the procedure. I think (not sure) someone said one of its immediate causes (or excuses, rationales) was a bigamous case. So bigamy did precipitate this act (if my notes do not deceive me).

It was said that the Marriage Act was seen as an unreligious (not anti-) measure, as Erastian, and thus offended the church which did lose power to the state. It was seen as a measure intended to give parents and others in authority over unmarried people control over who they could marry. Thus it was a way of protecting the property of a family (the family-clique system). At the time the way the way it was said to affect women would be they could no longer be fooled by a male fortune-hunter. The only way in which women as a group were consciously supported at the time was through strict settlement which was said to protect women. Actually it protected her as a member of a specific family who supported her. So again what’s supported is the family system and the members who obey the behests of those in charge at the time.

What happened was gradually custom caught up with the law, or one could say law facilitated and even created new attitudes: so the act worked to make religion less central to the important act of marriage, and it made bigamy less easy to get away with. From this perspective it was irrelevant to the growing desire for companionate marriage.

Again and again it was said there was a lot of vocal opposition to it, but after a while it seemed that the opposition was of the type often seen when a new measure is promulgated: silly reasonings to support an unexamined (stubborn) resistance to change. Anything that could be thought of was produced. So the act was no good as it imitated the French in giving parents control over children. So there was a preponderance of propaganda against the act. However, since it passed and was not overturned, there were enough people to support it, and the panelists named some respected intelligent people at the time who wrote treatises in support of the act. It seems the grounds for the support were Erastian: pro-state and regularization, what would be uniformity and stability to marriage.

At the same time it would be fair to call it plastic legislation: it was written in such a way as to allow for many abuses to carry on. Those explicitly not covered by the bill included all Scotland, Jewish people, the royal family, Quakers, and anyone living across the seas.

The act was mostly represented in novels. What preoccupied novelists was often what marriage itself meant. The larger society in general (most people) continued to care most about sons as those who inherited the property. Daughters were vehicles for exchange. (This idea is made explicit in Richardon’s Clarissa where the vicious James Harlowe declares women should be seen as chickens for other men’s tables.) Central to their existence (as seen in mythic norms) was their holding onto their virginity before marriage. (So parental control would seem to shore this up; only the protest seems to me to show that men cared more about their sexual access to women and insofar as this act seemed to cut that off, they instinctively resented it.) One finds male figures becoming victims in these novels (not women). They often figure as the innocent clergymen who tells the story (as in The Vicar of Wakefield).

I also found three articles of interest, one by Ms. O’Connell: Erica Harth, “The Virtue of Love: Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act,” Cultural Critique, 9 (Spring 1988):123-154; Lisa O’Connell, “Marriage Acts: Stages in the Transformation of Nuptial Culture differences,: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 11:1 (Spring 1999):. 68-111; Gustavo Costa, Un Avversario di Addison e Voltaire: John Shebbeare, Alias Battista Angeloni, reviewed by Hannibal S. Noce, Comparative Literature, 20:1 (Winter, 1968):78-80.

To conclude, there does seems to have been widespread voiced opposition to the act. This opposition may have come from the usual stubborn distrust of change by the generality being used by specific unscrupulous individuals and groups of people on their own behalf. People also like the noise and excitement of controversy & detraction; they will buy it with money & seem to pay attention to the speaker/writer/artist/music-maker.

I’m having more and more trouble getting myself to take down in legible stenography what I hear; it seems to take a disciplining of my hands and fingers I can’t quite pull off anymore. On top of that I’m too tired to read seriously or write blog letters at night. That’s why it has taken me so long to write these summaries and reports and why I’m blogging less.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Nancy Mayer:

“I enjoyed the blog on the seminar about the 1753 marriage act. I wish I could have attended. I have studied it as law more than as literature—starting with Lawrence Stone and progressing to actual court cases.

One of the arguments made before the act passed was by the untitled men who claimed that the act was meant to keep the aristocrats’ daughters from marrying their sons. They were not interested in the freedom of females as much as they were in the spread of wealth through marriage. The act did clear up some ambiguities about whether or not a couple was married to each other. The same problem continued to exist in Scotland , where the act did not apply. The main problem of the act turned out to be the statement that a marriage by minors without proper consent of guardians or parents was null and void. This led to some annulments twenty or more later and led to the act of 1822, which was so defective it was itself mostly repealed in 1823.

Nancy"

— Elinor May 5, 1:46pm # - Dear Nancy,

It was an unusually informative session. The first speaker read parts of the law to us. The novels chosen were appropriate.

It is clear that no one was thinking of freedom for females, nor indeed for males, but rather seeking to protect family property. The speakers (I think the woman who spoke on Shebbeare’s novel) said a number of times fear of male fortune-hunters stealing naive daughters helped fuel the act. We could ask then, had these men themselves (the law-makers were men) been reading too many novels? (joke alert)

You can see the concern for control (which was what Foucault said emerged as a real social force in the 18th century) in the attempt to make the marriage no marriage unless the pair of people had parents’ signatures. My sense from your comment (and others) is the pair went ahead without proper signatures. Then the girl had publicly lost her virginity and her parents saw that this inflexibility backfired. Here what the third speaker said was the ultimate argument in The Vicar (though I’d like to see a passage that indisputably proves this) is important: marriage is a natural act; people who are adults feel they have a right to marry (this is made explicit in Webster’s Duchess of Malfi where the heroine’s brothers murder her for marrying itself) and will go ahead and couple (with or without law) if you make it impossible for them to marry. That’s probably not so; people succumb to bullying and law, but the idea does point up that trying to stop marriage by legal means will often not work.

Thank you for your reply. I appreciate replies on my blog.

Ellen

— Elinor May 5, 1:54pm # - “Dear Ellen,

I’m glad to see we’re revisiting the Marriage Act.

I already once posted a link to the bigamous case that led to it so I’m reposting it here:

http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/lhr/17.1/leneman.html

A few points re: Ms. Hiatt’s POV though, that came to my mind while reading the summary.

The parental control was legally forced until a woman or a man were 21. Saying that it was required only for a marriage by licence is illogical, because every marriage required licence, only not the special licence that was allowing to marry without bans. All other marriages stillneeded the so called “marriage licence”. So the parents had legal right to object in every single case.

Saying that they could state their objections while the banns were read doesn’t make sense at all. Because either they had legal right to object or they had no basis for objections. The banns were being published to prevent bigamy, not to give the parents a venue to speak. And they didn’t need it, they had their say with the licence.

I would agree with the Tories. The Marriage Act was barbarian, misjudged, unsuccessful in preventing bigamy, subduing women under parental control and, moreover, making women easy victims of seduction.

I don’t think the opposition ceased because people accepted the change, rather sooner or later people get used to even very bad laws(even today). Esp. if the laws are made by men and its chief victims are women. Austen shows only negative results of the Act. I don’t recall any parent in Austen’s book using the Act to prevent their daughter’s marriage to a rascal. There are however contrary examples:

Brandon and Eliza. Eliza is seduced by Willoughby who abandons her when she gets pregnant. Before the Act Willoughby would be considered by law married to Eliza. Either he’d have to bear the consequences of his actions, or he would be more cautious and not seduce her in the first place. If he was already married he’d go to prison for bigamy.

Wickham talks Georgiana into elopement. Only Darcy’s sudden arrival prevents the deed. Without the Act Georgiana probably wouldn’t agree to go to Scotland because she wouldn’t have any reason to think her brother might prevent the marriage. Most likely she would inform him about her plans earlier, willingly, in a letter, what she finally did, but only once she met him in person. Then in fact the Act was only creating more causes for elopements.

Lydia and Wickham. It costs a lot of Darcy’s money to talk Wickham into this marriage because Wickham still hopes to marry better in another country. Before the Act that wouldn’t be possible. He would be considered married to Lydia by law, and he couldn’t marry anyone else.

The Act fought against clandestine marriages as those were most likely to enable bigamy, however, it doesn’t seem that the number of bigamous marriages became lesser after its implementation. It was still possible to marry two, three or more women in the same time, esp. in London, where, with the number of population there, the clergymen had little chances to check anything. If someone married in one place in London, and then went to another, the banns wouldn’t be published in the very parish where they might prove anything. Of course since the Act didn’t hold in Scotland still everyone could marry there.

It’s not true that the mandatory registration of marriages was successful. It didn’t exist in Scotland until 1855, and in England until 1837 the information didn’t include even the names of parents or the young people’s address.

In effect the information provided was saying something like: On June 6th John Smith married Henrietta Wilson. Now, if four days later a John Smith wanted to marry someone else in another place there was no way to check if it was the same person or not.

In theory parents couldn’t force their child to marry anyone, because the child always, both before and after the Act could say “no”, it of course looked differently in practice, esp. if there was no entailment. However, the Act gave the parents legal right to prevent marriage if their child wasn’t of age.

It is much different than it was in custom before the Act, and i.e. contrary to what the Catholic church did. In the Catholic church if there is any doubt whether a child married out of their own free will the marriage may be annulled, and the Canonical Law specifically forbids the parents preventing their child’s marriage. In the Church of England a father literally brings his daughter to church and gives her to her husband (I know it’s not necessary anymore but still practiced).

As I see it the Act was full of good intentions and very bad resolutions, and its effects were disastrous for many women.

Just for additional information there is also the previous, religious view represented in Austen’s books. In case not everyone knows the traditional religious view is that marriage consists of two elements: free consent of the young couple and consummation. So if people are betrothed they are considered just as married as a couple who already had the church ceremony but haven’t yet consumed the union. It was absolutely shameful to break an engagement. And a consummated betrothal was automatically considered as marriage. Of course religious view assumes that people are honest, so there is nothing that would prevent bigamy.

Edmund Bertram never proposed to Maria Crawford. I don’t think Austen would have him break the engagement if he did.

Edward Ferrars doesn’t break his engagement to Lucy Steele. Also Elinor doesn’t expect he would. She considers him another woman’s man. Lucy eventually breaks the engagement.

James Morland breaks his engagement to Isabella, but only after he learns she was cheating on him.

In P&P the attitude to Lydia’s situation changes along with the news. Elopement alone isn’t yet thought such a problem until it’s revealed that they didn’t go to Gretna. Later Lizzy is relieved by reading Lydia’s letter which confirms that at least Lydia thought she was really going to marry, not live in sin. In thiscase Wickham is a seducer. Lydia never agreed to his real plan, she agreed to marry him. Of course there’s no difference from legal POV, but it was making difference for Lizzy and Jane. Also Darcy tries to persuade Lydia out of the marriage, but once he sees it’s really what she wants he doesn’t use any legal tools to prevent it, on the contrary, he promotes the marriage.

Darcy in his letter to Elizabeth writes that Georgiana was only persuaded to believe herself in love, by that making sure that Elizabeth knows he didn’t break a love union.

In Persuasion Anne is talked out of marriage by her family. We can easily imagine that if Darcy’s parents were alive he wouldn’t be free to marry Elizabeth, and his mother wanted him to marry Anne anyway.

From my point of view Austen clearly preferred the religious marriage to the civil one enforced by the Act. The opinions supporting the Act are given by such characters as Collins or Mary Bennet.

Sylwia”

— Elinor May 5, 2:13pm # - From Nancy Mayer:

“The same arguments were raised in 1822 and 1823 by men who wanted a chance to marry a rich girl or for their sons to do so. The rate of illegitimacy climbed as population did but, according to Gillis, it was not the laws regarding marriage which caused this: Many lower class females did not want to marry at all and they gave away the babies, or killed them.. That was the reason for the foundling hospitals.

Still, it has not been until the present day when most of the rules have been relaxed that the number of marriages has fallen.

Most parents were not monsters to their children. they did limit the girl’s circle of friends to those she could choose from …, a girl took her husband’s social status so a girl who married a footman took on the status of a servant’s wife. That would limit their social life. Also, runaway marriages were devoid of settlements which were often the only protection the brides had. I think both John Byron’s wives would have been better off with settlements, though in their cases they were both of age.

You are right that parents could be abusive, but I do not think it fair to blame the marriage act for that. A bully and an abusive parent would be abusive no matter the law, It was the fact that the girls were minors which made them subject to the parents and not the marriage act.

Any one could marry without permission after they were 21 so it wasn’t as if they were forbidden to marry at all, just to have permission to marry before they were twenty one. It also was not only the aristocratic parents who complained. The banker Child objected to his only daughter marrying an earl. He chased after them as they ran to Scotland . When they married at Gretna Green , he changed his will so that his fortune and his bank went to the oldest daughter of that marriage Other cases were of older women marrying boys for what he would someday have.

As you know, from the cases of Mary Darby Robinson and Charlotte Turner Smith even with the need to ask permission, liars managed to marry girls. Both the husbands in those cases said they had expectations.—expectations that never came to fruition.

Interesting views on the subject.

Nancy

— Elinor May 5, 9:08pm # - Dear Nancy,

Yes, my research into 19th century customs and laws shows that women below gentry did not want to marry. They feared being saddled with an abusive, drunken man who could control (or take) their salary.

I agree most parents did want their daughter to be happy or do well; however, some did trump this by family considerations and it’s easy to rationalize your own desires. The point made at the meeting (by others beyond me) was that this act gave parents more moral ammunition. The state has prestige. So the bullies now had a freer field. Consider Lady Catherine de Bourgh: suppose she had had power over Darcy’s estate (had he been her son say).

Charlotte Smith’s marriage seems to me (from what I’ve read and I am very interested so there have read a good deal) a tragedy destroying her life inflicted on her by her father and step-mother. They wanted to get rid of her and at first she was fooled, complicit; only as her husband turned out so badly and she grew older did she understand.

I see the act as one reinforcing the power of the community and families over both men and women. In that it fits Foucault’s ideas (as I wrote).

What is striking to me is how lipservice was paid to the problem of bigamy. Men committed bigamy with impunity. Once the woman lost her virginity and was seen to have lost it, she was at an extreme disadvantage if she wanted to be treated as a respectable woman. It was said the movement for the act was precipitated by a bigamy case. But if we look there are so many loopholes, the act did nothing to help such women.

In fiction, except for a remarkable exception late in the 19th century bigamy (Henrietta Stanard's The Blameless Woman, is presented as done by “femmes fatales”. Nothing really could be farther from the truth. I investigate this in my paper on Anne Halkett who was deceived into a bigamous marriage during the interregnum.

So no one cared about the woman. Other women in power or lucky did not identify with those who suffered at all, and there were so many suffering from false marriages (i.e., bigamy).

E.M.

— Elinor May 5, 9:09pm # - Dear Sylwia,

Thank you for your reply. From what I can gather the act was intended to shore up the family and property systems and those passing it did not care about individual woman’s fates except insofar as the idea they might be “fooled” and deluded into a “bad” marriage by a fortune-hunter. This level of thought is crass and without depth and does not begin to touch the various issues at hand.

I don’t agree with either Tories or Whigs as I’m not an eighteenth-century person and don’t (can’t) go back to re-enact their stances at all. I took the view in my blog that this is a movement to survey and control through a state apparatus, justified supposedly by regularizing and preventing “false” marriages; for example, bigamy; and ceremonies that were ambiguous (vows in the present tense or vows in the future tense accompanied by sexual consummation, the two most common ways of “marrying” before the act). The Tories were pro-Church and saw it (apparently) as a way of taking power from the church and this is one of the readily available ways Dr Primrose argues against the act.

But (as the speaker suggested) Goldsmith’s novel goes deeper and says the act is not enforceable and will be continually subverted by people’s behavior because marriage itself (coupling, chosing a partner) is in itself an inalienable right. This sort of thinking returns us to the Enlightenment ideas about individual freedom and the kinds of truths the French revolution embodied in their Declaration of the Rights of Man.

As we know, ruthless and brutal groups of people can stem such “rights” by brutal murders, destruction of property, throwing people in jail, harassing them, torturing them. In the present context inalienable rights seem to be frail and for each generation (and many individuals) repressible.

I agree with you that this enforcement on conformity would fall hardest on women and was even seen to (meant to—as in the above stupid way of putting it), though the terms in which it would maim or ruin her life are that she would not be able to chose a partner she might be congenial with and have a decent personal existence. It’s an act against companionate marriage in this sense, or only allowing it insofar as the family authority figures thought the compatible person would be someone who would shore up their interests (get them jobs, money, prestige, land, all the things “connections” hold out still).

Neither before or after the act would Eliza Brandon or Williams be any better off. Eliza Brandon (Colonel Brandon’s cousin whom he loved and who was the original heir to the property) would be treated worse after the act in the sense that the guardian had more moral authority, but he did force her to marry a wastrel horrible son before with little trouble. No one would help Eliza Williams. What we are talking about here is custom: custom discarded women, did not protect them form their families or husbands, and if they were seen as unchaste, scapegoated them and let them be destroyed in the streets.

Custom is more important shaping of individual destinies in any particular moment in time. Custom and law interact and after a while a law can change custom but only if people are headed that way. THe US law against drinking (prohibition) was repealed because of deep custom: people desire to drink and kept doing it.

You write:

“The Act fought against clandestine marriages as those were most likely to enable bigamy, however, it doesn’t seem that the number of bigamous marriages became lesser after its implementation.”

I agree with all you said and think the reason for this is men wanted the bigamous out to be there. It didn’t hurt their reputations or property; it did women’s and it enabled men to seduce women. So nothing was done.

The Marriage Act was not intended to protect women from men’s sexuality, only to control them on behalf of their family’s aggrandizement ideals.

Finally, just on engagement: you’re right, it was taken seriously, mostly because the young couple was treated as a nearly married one and left alone. In many circles sexual intercourse might and would take place between the couple. We see the results of a broken engagement in this light in Anthony Trollope’s The Small House of Allington where Lily has lost her virginity and cannot break her psychological thrall or get beyond her shame. Austen is showing something of this psychological trajectory in her portrait of Marianne Dashwood.

E.M.

— Elinor May 6, 6:48am # - "Dear Ellen

William Mulready’s painting of a scene from The Vicar of Wakefield which illustrated your article on The Marriage Act Panel at ASECS is not contemporary with the novel. It was painted about 100 years later, in 1842.

Speaking of illustrations, The Marriage Act is of interest to Hogarth scholars: for instance, it can be argued that Tom Rakewell was actually married to Sarah Young in A Rakes’ Progress( 1733) because he had given her a ring, and a written statement of marriage, and had consummated the marriage. By law and custom before 1753 this was a legal marriage. Commentators have always said that Sarah Young was merely seduced with a promise of future marriage. This is an important point in understanding Hogarth’s narrative. it means that Sarah Young’s child was legitimate, had legal rights, that Rakewell’s later marriage in church was bigamous, and explains (at least partly) Young’s devotion to the Rake.

Hogarth married his wife without her father’s consent or knowledge when she was a minor.

Pat Crown"

— Elinor May 6, 10:33pm #

commenting closed for this article