Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

ASECS, Portland: A Miscellany · 8 April 08

Dear Harriet,

Here is my third and last report on the sessions at 18th century meeting in Portland, Oregon, this year, on what I saw of Portland itself and its central museum. The variety I’m going to tell about here suggests how unreal are most attempts to characterize in any unified way what’s called an age.

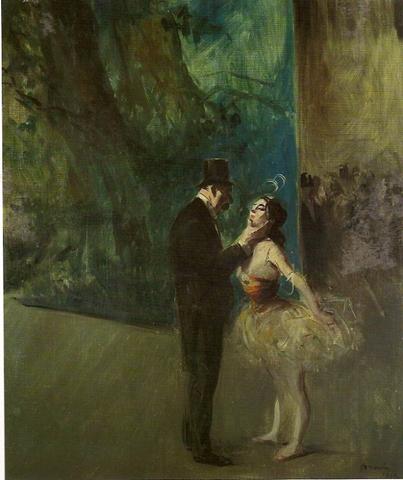

Jean-Louis Forain (1852-1931), Dancer and Abonné at the Opera (1972) (part of Portland Museum exhibit)

First, an intendedly fun and (given my projects on Austen and Palliser films) a relevant session. I went to a performance late on the last day of scenes from Charlotte Charke’s burlesque afterpiece The Art of Management; or Tragedy Expell’d. It was prefaced by a short explanation of how Charke came to write this play: she had been fired by Rich; the play was intended to expose his greed, enforced pay cuts on vulnerable employees (including actors), and what Charke conceived of as his stupidity and total lack of taste. The decision had been made to have a male (Conrad Burnstrom) play the part of Charke and a female (Elizabeth Kowaleski-Wallace) Headpiece (a lead role, a technical and business person in the company), and that added to the piquant amusement. The performance was very well attended; the hamming up of the parts was not overdone. I liked some of the hystrionics and clever comic props (such as a lawyer carrying a brief case). This is the third play this group of people have done over the past 6 years: they began with a Restoration comedy in Los Angeles (an ISECS), and two years ago did another. Perhaps they’ll attempt sentimental comedy next time.

I wish I had gone to more film sessions. I went to one on Friday late morning. All but this one were scheduled against other topics I wanted to hear about and the only movie covered in all of them, which I had seen was Peter Weir’s Master and Commander. What I did hear was stimulating and made me feel I’m not alone in finding fidelity as an evaluative criteria inadequate (when not plain wrong). I apparently missed a paper on Michael Winterbottom Tristan Shandy which developed a taxonomy on types of film adaptation; I would have liked to hear the paper on the problem of history in Coppola’s Marie Antoinette.

Sophia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (Kirsten Dunst) comes to court (2006)

Louisa Shea discussed how the way Sade is regarded by the public and the kinds of film adaptations that are popularly made make it very difficult to translate his books truthfully with an intelligent critical perspective. His books are seen as unfit for heritage films which (she assumed always do) celebrate the luxuries of the upper classes and provide lavish displays of opulence. She suggested most films of Sade’s books fall into 3 categories (or subgenres): the avante garde (Bunuel’s art film, Screams in favor of Sade), porn (exploitation films like the Swedish Justine et Juliette) and biography (biopic, the 2000 Quills). Pazzolini’s Screams in favor of Sade consists of 80 minutes of a black and and then white screen with no images; one hears 5 voices and then total silence. The film-maker rejects traditional purveying of images which distort reality and rejects all poetic justice. Pazzolini’s film consists of disturbing graphic scenes of violence and torture, obscenity (by 4 debauched old men) and sexual abuse (of a child). Pazzolini said the film was a political commentary on fascism; we are not allowed to identify with anyone as victim; the final scene consists of people watching a murder using binoculars. We watch these people. She thought the 2000 Quills was a tongue-in-cheek delight, bizarre and cheerful; we watch a gleeful vendor reap profits from selling Sade. Much is made of Sade’s activities as a writer. The first two films are impossible to integrate into a commodity driven entertainment industry; the third is a consumer feel-good film, without much humor, and tasteful intellectual evasion.

Ralph Sterne gave a paper on the German Nazi film Andreas Schulter. Schulter was a baroque sculptor and architect whose regal militarist buildings had been thought perfect for Nazism, were torn down during the communist era; one is being rebuilt right now. Mr Sterne went over Schulter’s real career and life, and then showed how the actors and film-makers used events from it to project the anxieties and fantasies of Nazism. The film ends tragically (the hero falls, leaves prison, & then moves into a “realm of light”), and appears to be one worth seeing. Mr Sterne spoke of the importance of shooting in real locations, uses of well-known actors who come to the screen with symbolic baggage, and how difficult it is to know what viewers really thought of the film.

Jack Aubrey and Stephen (Russell Crowe and Paul Bettany) in Master and Commander (2003)

A young Spanish professor, Diego Tellez Alarcia, gave a remarkably well-organized, lucid, and detailed exposition on Master and Commander, an adaptation of several novels by Patrick O’Brian. Mr Alarcia went over the type of film M&C represents, the real historical & contemporary events (one involving the USS Essex) it alludes to, its relationship to O’Brian’s novels, and how it functioned to whip up patriotic emotion after 9/11. Mr Alarcia first used Krakauer (who I’ve read) to argue that films provide a new way of studying history: we can study our culture as an engine of history itself as well as a mirror of society. Films are a new way of writing history as valid as speech and the written word. Mr Alarcia went on about how much effort was put into making the details of the film historically accurate (ship, food, clothes &c). The genre this film belongs to also is the swash-buckler, the rebellious adventure film, the tongue-in-cheek (Captains Courageous, Mutiny on the Bounty, Billy Budd, Pirates of the Carribean). I learned something new about O’Brian’s career: I had thought the Jack Aubrey novels are a roman fleuve, but did not know that O’Brian translated 30 books from French

Then I’m fond of romantic and sensibility authors & art. So on the Thursday morning, I went to a session on “Gothic Romanticism and Politics,” and (among other papers, a couple of which I’ve discussed under “women’s writing”) Katherine Kerberger gave such a clear coherent, and detailed account of Byron’s Manfred one need not have read it in a long time to learn a great deal about this play. She suggested that Byron must have known of Marlowe’s play, used Gothic trappings, strips the Faust legend of medievalism and is atheistic, pays tribute to pagan impulses. Manfred’s connection to humanity is through his sister, Astarte, is Hamlet like in its longing for annihilation. Manfred does not seek power or knowledge, but not to be. When she said that in the play sorrow brings knowledge I was reminded of Germaine de Stael’s defense of passionate romantic writing in novels.

After lunch that first day, Jim accompanied me to “Making Selves, Sense and Sounds: 18th century French fictions.” Ted Braun’s paper on Prevost and Rousseau was a meditation on the relationship of autobiography to fiction, instanced by Rousseau and Prevost. He discussed the dangers of autobiography, the influence of Prevost on Rousseau, Cleveland, Manon Lescaut, & The Confessions. Isabelle Demarte suggested the form and content we find in fictional letters of the era shows the influence of non-fictional letters, and that non-fictional letters are themselves then rewritten to make them more respectable. The two genres share features: the situation of addressing someone; the representation of a presence; the necessity to create some coherent form that resembles an imagined letter. Jack Iverson’s text was Beaumarchais’ The Barber of Seville, his topic the anxiety 18th century people felt about how calumny (and contumely) could be spread because of the ease of manipulating public discourse. He seemed to suggest Beaumarchais nonetheless was for free speech.

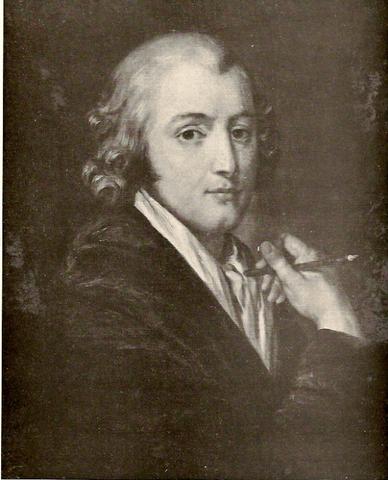

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Self-Portrait (when young, age 19)

The French 18th century & age of sensibility was also represented by one of the plenary lectures: on Friday around 2:30 pm, Bernadette Fort’s “Arresting the Gaze: Greuze’s Self Portraits.” She discussed Greuze’s self-portraiture as shown in three paintings he did of himself in the same pose, one as a very young man (hopeful), a second in his maturity when his marriage was falling apart (a time of upset reflected in the painting, disenchanted, disappointed), and a very late one, himself as an old man (a kind of ghost of himself). He embraces, immortalizes and in the first and last shows himself with one of the prosaic instruments of his art. She felt the portraits have a modern feel & startling intensity, & asked what was the point of fashioning himself in this way at three intervals.

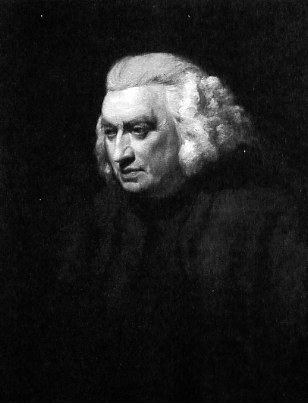

As to traditional English figures I’m fond of, I heard but one paper on Johnson: Lisa Berglund’s witty “I am lost without my Boswell.” Her theme was the intersections of Boswell’s Life of Johnson with the Sherlock Holmes’ tales by Conan Doyle, ostensibly written by Watson. She showed the limitations of biographical understanding. Johnson was also included in a traditional take on Augustan 18th century, represented by the second plenary speech, Howard Weinbrot’s discussion of the evolution of January 30th sermons across the long 18th century. At the Restoration a law was passed requiring sermons to be given on the anniversary of the beheading of Charles I; they were intended to be fiercely pro-Monarchical, pro-Anglican church, Tory, but gradually the sermons given by so many different people altered so that towards the end of the era some of these sermons were defenses of having beheaded Charles I. His subject matter included intolerance, bigotry, religious rage, an examination of the sources of cruel & irrational behavior. He concentrated early on Gilbert Burnett and Defoe, towards the end on Swift, Johnson, and Sterne’s sermons. I liked some of the quotations, for example, apparently from a later 17th century sermon: “Who knows not that the generality of men speak as their preferment leads them?” At times it felt like I was listening to a noble sermon, especially when Mr Weinbrot quoted Johnson.

Samuel Johnson by John Opie

Portand is a small city, and we stayed in the heart of the cultural district. The club (reciprocal with the Williams Club in NYC) was first built in the later 19th century by local civic-minded businessmen, and was long a center of conservatism. Today it fronts a lovely park area around which are museums, an art center (for plays, opera, symphonies), a movie-house, and nearby shopping. Inside we experienced old-fashioned luxury: high ceilings, two sets of faucets in the tub, two lovely large rooms, and a handsome dining room (which we were told is sometimes used for weddings). Jim took walks and said there are some very run-down areas; apparently the city throve when its river was central to commerce, but when trains replaced water, and the depression came, commerce went to Seattle. Jim said he could find only three decent restaurants he would want to go to in our walking vicinity. I could see a traditional of socialism is not dead: the leading politicians are democratic, the newspaper was not rabid, and there were comfortable newly built trolley cars which would take customers anywhere within the city bounds for free, and out of bounds for a reasonable price.

On late Friday afternoon we left the conference early and spent around 3 hours in the Portland museum. The representative collection from the 19th century on is decent; what was the interest though was an intelligent revealing exhibit of pictures of all types by Degas, Forain, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Jim said the exhibit made him no longer look at Degas unfavorably as a voyeur; in the pictures we saw Degas, Forain, and Toulouse-Lautrec saw the women dancers, singers and entertainers empathetically, and the “subscribers” (rich, debauched, anonymous elegantly guardedly dressed males) as incapable of not preying on them. The pictures revealed the alluring excitement of such night-life, the hard & sometimes humiliating work the women endured, & amid the assumed indifference of the faces and bodies everywhere intense pathos.

Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), Dancer (1895-96)

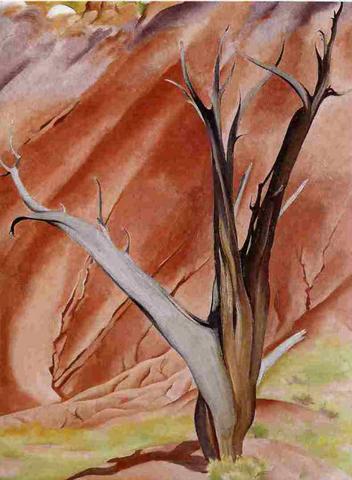

So another worth while trip. I can’t very well discuss the conversations I had with friends at and between sessions, the woman’s caucus, but would like to say I enjoyed three long conversations with three different women going and coming from Washington DC to Portland on the Southwest plane-bus. Jim will not sit in the center seat nor will I so I sit near the window and he on the aisle seat. He usually buys our number early so we sit up front and each time a friendly woman sat between us. I saw the rocky mountains and the desert for the first time. They looked like Georgia O’Keefe paintings (though not the one I picked out, which I chose for its closeness to the 14 year old dancer just below).

Georgia O’Keefe, Geralds Tree

There are much fewer people in the southwest and in the Portland area than I’m used to. I’m not keen on crowds or noise. Still as ever I was fervently glad to come home, see a region thick with lights, houses, active life, & get back to our house and sleep in our own bed.

Degas (1834-1917), Little Dancer, aged 14 (1880-81)

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Clare:

“I loved the Degas dancer. I saw a copy of it in about 1962 in an art gallery in Coventry. It really turned me on to both Degas and sculpture.

I was interested in your views of Master and Commander, Ellen. I saw the film here, but thought it was entertaining, but not a patch on the books. Aubrey & Maturin are really rounded out characters in the books (I know I’m sad, but I’ve read them all). Much is made of the two men playing chamber music and arguing about science in the books. I also thought Russell Crowe was far too American for the character, but Hollywood pays & Hollywood gets whom it chooses.

Clare”

— Elinor Apr 9, 1:13pm # - The problem is historically inaccurate films such as Marie Antoinette and Quills is that the popular image of the characters merges with the film depictions.

Who would want to read Sade after watching Quills?

I just discovered your blog and love your emphasis on the 18th century. Do you mind if I add you to my blogroll?

— Catherine Delors Apr 10, 4:23am # - Dear Clare,

Mr Alarcia provided a lot more information about Master and Commander than I transcribed. For example, the origin of the incident in O’Brian’s book (and thus the film) was an 1805 incident in the Napoleonic wars where HMS Surprize pursued and destroyed a French privateer. The film was based on at least 3 novels by O’Brian: Far Side of the World, Desolation Island, and Master and Commander. It was also seen at the time as promoting war values and militarism and patriotism.

Crowe is Australian. Yvette loved Paul Bettany, and my favorite parts of the film were the ones where Darwin-like he went collecting specimens. I liked the friendship between the two men. I deplore the lack of any women except as sex objects. It was, though, a sexy film: male homoerotic with lots of phallic imagery. The script (as I recall) was witty too.

Ellen

— Elinor Apr 10, 6:59am # - Dear Catherine,

I’d be delighted if you would add me to your blogroll. Please send me your blog address and I’ll add yours.

I really regretted not going to the session which discussed the mini-series Aristocrats. Tillyard’s book is superb and accurate. I see also there was a paper by Tim Erwin on “Landscape Picturesque in Austen films.” If anyone coming to this blog heard either of these papers, I’d be grateful to know the thesis and anything else that was said.

Ellen

— Elinor Apr 10, 7:02am # - From Clare:

“Strange how Australians now seem nearer to Americans, culturally, than to us. I knew that he was an Australian, yet he seems very American as an actor. I agree that the collecting scenes were charming. Particularly the scene where the boy gives Maturin the Galapagos beetle.

Clare”

— Elinor Apr 11, 2:35pm # - I enjoyed reading this very much, and was intrigued by the thought of Holmes and Watson as influenced by Johnson and Boswell – this had never struck me before, but, as soon as it’s mentioned, the similarities in the two narratives jump out.

I also really like the Georgia O’Keefe painting of the tree.

— Judy Apr 11, 3:24pm # - Clare wrote:

“Strange how Australians now seem nearer to Americans, culturally, than to us. I knew that he was an Australian, yet he seems very American as an actor. I agree that the collecting scenes were charming. Particularly the scene where the boy gives Maturin the Galapagos beetle.”

This is interesting to the Trollopian. While I feel that the culture which released Anthony Trollope from his depression was Ireland (as that’s what he said, and we can see strong allegiance and fondness for the Irish even if he was willing, horribly, to consign the poor Irish to death from starvation rather than disturb the property laws), Mullen and others have argued that he had a strong allegiance to America, and certainly in his book we see him really keen on American values which he argues are a kind of reconfiguration of English ones in a colonial setting that requires strong entrepreneurship and disssolves hierarchies. When he goes to Australia, he sees the same thing and he likens Australian culture to American.

For me this means anyone writing about Trollope’s travel books needs to write about North America in tandem with Australia and New Zealand for his love of both places comes from what he perceives as the similiarities in them he is attracted to.

He’s not altogether right of course, and people here or others then may be or have been more struck by the differences. For Europeans, Australia began as a penal colony; it’s arguable it was the first archipelago of slave-labor and extermination camps anticipating all those of the 20th century—Hughes’s Fatal Shore is an important book for the 21st century. IN reading about Australia I became convinced the reaction of the people who built the nation after this traumatic event in many of their lives evolved a communitarian culture, one which was strongly pro-labor or socialistic; this was broken up in the middle 20th century by reactionary groups using racism to divide “whites” from others and encourage strong conservatism; nonetheless, the spirit remains. IN the US the reaction of people who came from such different places to a huge country most of which was habitable (no deserts), which only (I say this ironically) required the extermination of the peoples on the ground (which the newcomers did) was a strong individualism; the communitarian spirit is not in the American grain as William Carlos Williams puts it.

I hasten to say all generalizations are only that and individuals are individuals; we are talking of general conceptions, stereotypes and what a culture seems to encourage.

Ellen

— Elinor Apr 13, 8:07am #

commenting closed for this article