Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

BSECS Jan '09: Life-writing · 19 January 09

Dear Friends,

Another brutally cold night; tomorrow, Inauguration Day for Barack Obama, promises to be as frigid. A high point for me today was on UTube to watch Pete Seeger, age 89, flanked by Bruce Springsteen and his grandson, singing “This land is your land, this land is my land” to the thousands of people who gathered at the Lincoln Memorial yesterday. Tomorrow I’ll turn the TV around 11:30 am to PBS: as I watched Obama win the nomination in the imagined company of Lehrer, Shields and crew, so I’ll watch him sworn in.

Tonight I’ll carry on my account of the Admiral and my time in the UK last week. Thursday I told of all our non-conference activities; now I’ll offer summaries and commentaries on some of the papers & talks I heard over the course of the 2 and 1/2 days of the BSECS meeting at St. Hughes’ college (once an all-women college). The theme was ”’Lives’ and lives” or the difficult of writing lives from actual experience and records of life and history. The sessions were on how people lived and what records they left of their actual existences. I cover Elizabeth Montagu’s life as a saloniere, businesswoman, blue stocking, writer, and friend; Sarah Scott’s radicalism (she actually argued for the importance of the ties of friendship over families which are presented as mostly or often adversarial); and Anna Barbauld’s class discomfort with the bluestockings; biographical writing & Johnson’s lives, Richardson’s Grandison and Clarissa; Dyer’s much-anthologized but little-discussed “Grongar Hill”; Ann Radcliffe’s Gaston de Blondeville and attempt to find a foremother poet in Marie de France, De Sade’s Justine and Juliette; Mary Wortley Montagu’s Turkish letters, & a little known travel writer to Constantinople, Elizabeth Craven.

The 2 and 1/2 days began and ended with plenary sessions. The opener, on Tuesday, the 6th, was a roundtable. Jack Lynch talked of what led him to be interested in “the Lives and life of Samuel Johnson.” Lynch suggested that as we can still take Johnson’s literary theory and criticisms seriously, so can we take his thoughts on biography. Johnson is the rare writer for whom one can organize his writing around his lifestyle. Tim Hitchcock said life is connected to reality, about which we are dependent on documents. These have increased expotentially since the advent of the Net. We have an infinite archive on line. Gary Day did a long and informative talk based on Defoe’s Moll Flanders where he attempted to come up with a new label and criteria for readers today. Helen Berry’s concluding talk was on Giustro Ferdinando Tendresse, a castrato and virtuouso musician, played in the “big time” next to a niece. What are the good materials for a biography of a castrato: popular printed versions of high level scandal, satires, caricatures, scurrilous false stories to see what Her Majesty says, the queen is right there. And written accounts of daily life at courts; libretti, letters, diaries, pictures, favorite rooms and objects.

The discussion afterwards included the questions, Is there anything that distinguishes an 18th century Life from a 17th or 19th & 20th century one? How does one take such disparate materials and turn them into a document that captures some reality coherently? I had this problem when I tried to write a life of Anne Finch. I felt I was imagining too much from general histories, drawing too much on secondary materials that had not enough direct connection to Finch, even though I had much that was directly connected too.

It was then time to go to the individual sessions. The first one I went to was one of the best in the conference that I attended: Carter, Montague, Barbauld, about the so-called mid-century Bluestockings. Elizabeth Eger is working on a biography of Elizabeth Montagu where she is looking at 18th century history through the prism of this woman’s complicated roles at Newcastle (a rich man’s wife whose money was in coal), London & Bath (a society hostess & Shakespearean critic.

Elizabeth Montagu (1818-1800) after Joshua Reynolds’s portrait

The materials consist of the partially published collections of letters by her descendents, particularly Emily Clemenson whose book reflects ideas of early 20th century feminists. Eger talked about how Montagu’s life distrupts our notioins of a life which shows progress, and how her female selfhood can be seen in her networking (patronage of) with friends. Eger highlighted a box of friendship Montagu had made with the pictures of hereself & 3 friends: Mary Cavendish, Duchess of Portland, Mary Delany and Mary Howard.

Two of the women on the box of friendship

The celebration of her in pictures like Richard Samuel’s 9 Muses of Great Britain is as much about nationalism as illustrious women.

Nichole Pohl talked of how Sarah Scott’s radical ideas in her life and Millenium Hall marginalized her in her era. Scott’ ideal was a household based on friendship and emotional fulfillment, self-possession. Scott showed we must move from biological to conjugal ties; she was pessimistic about empathy being learned across human boundaries. In Millenium Hall we meet many girls whose lives have been partly ruined by families and non-family relationships. A typical story: Miss Mansell ahd a male benefactor who turned out to be a predator & dies; she is taken in. Scott depicts the struggles between filial, marital & duties assigned to friends, and the duty to oneself. A kind of elective affinities ends up binding characters. Scott married badly and learnt to long to escape these duties; what she wanted was emotional refuge.

Said to be Anna Barbauld (1743-1825), attributed to Richard Cosway

William McCarthy talked about Anna Barbauld’s unspoken alienation from the bluestockings. After reviewing Barbauld’s life, her first marriage to a dissenter, her social awkwardness (which she realized), McCarthy showed that Barbauld held herself apart. He quoted one of her letters where she shows that she was made uncomfortable by taste and upper class manners (snobbery). She found that their talk assumed a more upper class woman than she. McCarthy brought out how Barbauld was really a woman of a much lower class standing than the leading bluestockings and that her keeping her distance from them did not mean that she was not a feminist so much as that she was not acceptable to them unless she were to try to ape their upper class ways, dress, and politics. He made out a moving case for understanding why she chose to run her dissenting academy with her husband in the independent way she did. Her radical politics were a product of her marginalization as a dissenter. The letter she wrote arguing against women’s education is usually presented as written to Elizabeth Montagu but it appears to have been written to someone else and so we don’t know its context. The original is found otday in the papers left by Georgiana Spencer Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire. There emerged from his talk a complex and sympathetic woman.

Broadview edition of her poetry and prose (excellent choices, one of the editors is McCarthy)

In the later afternoon I went to the panel on Godwin and Wollstonecraft. Three papers. One on history in Mary Wollstonecraft’s writings was couched in abstractions and I couldn’t make out what was the point of it, what the author was trying to say about Wollstonecraft’s use of history (if anything). The second was by David O’Shaughnessy, one of the editors of Godwin’s diary and autobiographical writings slowly being published by Oxford. He gave an insightful account of Godwin’s personality (some of this from Godwin’s biographies), his disappointments especially, and how he brooded on Hazlitt’s account of his work as utterly ignored by his contemporaries. Considering his life (early death of Mary, his harridan 2nd wife, Mary Shelley’s running away with Shelley, Shelley’s irresponsible behavior and early death, and Mary’s return), I was not surprized to learn he was often depressed. Rowland Western showed how Godwin was closely influenced by 17th century radical thought: gov’t is evil most of the time (Godwin thought Hume’s idea that 1689 was a great moment for liberty appalling); human contacts are changing as a new sympathy spreads, yet in his novels we see both misanthropic heroes and the importance of a happy domestic life. Godwin’s ideal was the disengaged self; he sought to do justice to the need for human sympathy, social solidarity and individual independence; his Life of Chaucer incorporates his understanding of the importance of social life.

Wednesday and Thursday were both long days. Two sessions in the morning and 2 in the later afternoon; book tables, talk inbetween sessions, and a plenary session on both days. On Wednesday starting at around 7 there were drinks, then a concert: three students sang songs associated with three women singers of the era (complete with short biographies of the women), finally, a late-night annual dinner. The Admiral came to the plenary lecture, drinks, singing, and dinner on Wednesday night. We got home well after 10. Thursday was his day alone in London, and I came home by 6 to share pheasant and cream apple sauce, brussel sprouts washed down with wine with him, and rest before our gas fire.

For the first session on Wednesday morning, I went to a professedly old-fashioned session intended as an opportunity to study and discuss John Dyer’s Gongar Hall in depth. I’ve liked this poem (along with Dyer’s Country Walk) so it was intriguing to hear 5 people both close reading and trying to show off a special insight or technique or adversarial criticism. I learned Dyer does not use language to describe what’s in front of him but to reflect his mood; Dyer is mapping the countryside for poetry, that Coleridge’s techniques in his conversation poems are like this, that the poem has gothic sections (like when the setting sun clarifies the landscape) and sophisticated unusual prosody (trochees). That Dyer wants to get down enough accidental strokes because he feels he can’t contain the spread. Dyer wrote a letter from Rome’s Sacred Way, about triumphal arches and dirt, mouldiness, that he liked inarticulateness & apparent capriciousness as part of a design. Finally that it belongs to a circle of contemporary poems (e.g., “Windsor Forest””), as well as bringing forward a tradition stemming from Denham’s Cooper’s Hill, including Savage and Pomfret. Clare Bryant argued that acts of contemplation were intended to create happiness, and likened the poem to Finch’s “Nocturnal Reverie” and Ambrose Philips’s “Winterpiece.”

Something interesting I didn’t know before about this poem came out as a by-the-way. Dyer had been deprived of ownership of this property by his brother. Much bitter litigation had been undergone amid the family. Grongar Hill is in Wales (I knew this) and thus the poem mourns the loss of this piece of property, for despite all the assertions of happiness, it is a melancholy poem. This reading of the poem is seen in a old picturesque print, either partly inspired by the poem or showing how this landscape was imagined at the time:

I was again torn in the second morning session because there were two I wanted to go too. The one I didn’t was called “Women in the public sphere,” and I would have liked to known more about Anne Hunter (one of my foremother poets on the wompo festival site), and about what it meant to be a public woman. For my part I like to stay in—with the door latched on.

So instead I went to the session on Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa and Sir Charles Grandison. Lingering in the corridors, staring at books on the display counters, talking to friends made me late, and one of the four people hadn’t come. Still, the two papers I heard provoked new thoughts and developed interesting old lines of examination. Bonnie Latimer argued that one reason readers of the era accepted Lovelace was his use of expedient morality draws upon latitudinarian thought as found in popular sermons of the era. Lovelace, for example, echoes Tillotson. Joanna Maciulewicz discussed Richardson’s use of epistolarity to show that Richardson was fascinated by story-telling and writing itself. She quoted Haydn White on how writers imitate forms they are surrounded by, and connected this to Richardson’s strong self-conscious use of performance and self-reflexive passages.

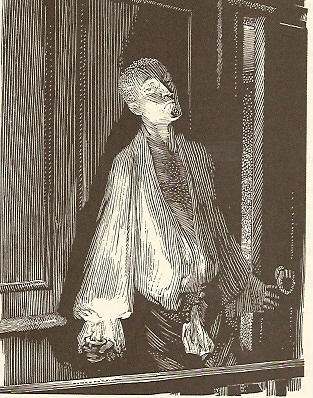

Lovelace about to rape Clarissa, illustration by Simon Brett (from the Folio Society reprint of Angus Ross’s 1st edition)

Harriet Byron abducted by Hargrave Pollexfen, Grandison

I was somewhat disappointed in this session (as I was by a number). There was an avoidance of controversial issues; no one among the panelists talked of the contradictions in readers that could take the cruel rationalizations of a rapist (and the modern illustration is also very mild in comparison with what is implied) as simply worldly. One of the papers (the one I came in on half-way through) went on about the presentation of religion in Sir Charles Grandison as if it had real validity and praised the depiction of Lady Grandison’s death. Ms Latimer did say that Grandison is a repellent hero (the calculating ways, the self-satisfaction, the inflicting of his vision on his sister).

After lunch came the second plenary session: Jack Lynch’s talk on “Johnson’s Lives.” These include his lives of the poets and uncollected lives, Boswell’s book, The Life of Johnson, hundreds of other lives of Johnson since; the lives Johnson himself lived, and his afterlife and influence in cultural history. He began with the difficulty of reducing a life to a text, how we have to impose a narrator on a messy actuality, and argued that Johnson was the first biographer to make subtly-understood and well-chosen anecdotes of a subject’s hitherto hidden private life central to his epitomizing narrative. It’s not that others didn’t focus on anecdotes before: think of John Aubrey. But they didn’t use them as integral parts of a subtly psychologized tapestry of life and works. Lynch felt that Johnson’s lives are genuinely innovative. He picked out a long passage from towards the end of Johson’s Life of Savage to exemplify his thesis. The discussion afterwards was lively as people brought up objections of all sorts.

The two sessions in the afternoon had 2 papers each. I found only 1 of the 4 persuasive. In “Gothic Crosscurrents,” Jenny McAuley discussed Ann Radcliffe’s Gaston de Blondeville, a posthumous novel, supposedly a narrative published from a manuscript found by a monk, & modernized by our narrator into the present framework.

She argued one brief passage in the book on Marie de France shows Ann Radcliffe saw Marie as a foremother fictionist & poet. Radcliffe had come across a passage about Marie either in an article published from a dissertation at the time or in Thomas Warton’s historyof poetry. She thought Radcliffe’s first biographer, Talfourd was influenced by Radcliffe’s portrait of Marie de France: like Marie, his Radcliffe was modest, distrusted the public sphere; had strong abilities. Marie as a women of letters does turn up in Mary Hays’s biographies; so this dissertation had been read by more people than Warton and Radcliffe.

These parallels are cliches about women then and now. Ive read Talfourd (whose memoir is printed as the preface to the Arno Press edition of Gaston de Blondeville) and its value is in reprinting Radcliffe’s journals and telling of her life with her parents. The allusion to the poet is a brief mention. I asked Ms McAuley if Thomas Warton (where she thought the writer of the article got his information and perhaps Radcliffe too from Warton) mentioned Christine de Pizan who is after all far more a feminist woman writer. McAuley said she didn’t know. That meant she had read only the passage in Warton famous for mentioning Marie for she presented no discussion of Warton’s book at all. She also did not appear to know much about the autobiography, liberal whig point of view, condemnation of wars, pictures of real sieges, and condemnation of forcing girls to go into poverty-striken wretched nunneries Radcliffe describes in her 1794 summer travel book.

But weak as this presentation was (not based on thorough reading of sources), McAuley’s arguments that Radcliffe sought a predecessor, saw herself as a poet, used Marie to endorse creative genius and modesty as a mode of behavior, and what McAuley had to say about Gaston (a murder takes place during a wedding; we see a corrupt feudal regime) were all creditable. During the discussion afterwards she said that Radcliffe’s retirement after the publication of The Italian (and much ridicule in the reviews) was not total: Radcliffe paid attention to reviews and responded to Scott’s & Seward’s comments on her. On the other hand, she had always wanted to keep a distance between herself and other women poets of the era. Why Ms McAuley didn’t know except for the idea Radcliffe was controlled by modesty norms. Perhaps she didn’t like the socializing and selling of selves; perhaps they were too radical (Helena Maria Williams and Charlotte Smith were pro-revolution throughout the 1790s).

The remaining 3 papers are quickly told. Also in “Gothic Currents,” Eva Gonzalez read a paper on the Marquis de Sade’s heroines, Justine and Juliette in a quick flat monotone, and argued that De Sade had a moral purpose in telling these hideous pornographic stories of great cruelty and that in his fiction sexuality is a mode of self-discovery. In response to one question, she did say she was ironic, but whether she meant that she was saying De Sade was not really moralistic and hiding behind his moral that evil flourishes and the good are destroyed; or that she was ironic (implicitly sarcastic and at a distance from these books) in her presentation of him I couldn’t tell.

I went to the session called “Turkey” because the titles of the papers suggested they were about women travellers I have read, one of whose work I like very much, Mary Wortley Montagu. The paper on Wortley Montagu’s Turkish letters included a critique of Edward Said’s Orientalism (a favorite target in this politically conservative conference) and a defense of Wortley Montagu’s presentation of the women in the harem on the grounds it was accurate in endowing them with real power & happy lives. I sympathize with the author’s desire to defend Wortley Montagu against castigating attacks, but find preposterous the notion that Montagu is anything but idealizing and naive, speaking out of her own relatively sheltered and protected niche:

!

Mary Wortley Montagu by Jonathan Richardson, ca. 1726

As someone else said, Wortley Montagu’s book is valuable for her style, wit, lightness of touch, her insights into a dream of cosmopolitanism and eroticism; the grit of the book is in the references to England, male politics, and the parts of her letters about her journey to Constantinople. It should be admitted that (ironically) Germaine Greer has also written a book where she idealizes life in a harem. Had she had to live in polygamous arrangements with males all powerful, she might not have done this; but Greer too has led a life of permitted relative power.

Laurence Williams’s paper on Elizabeth Craven’s journalizing of her trip to Constantinople was realistic: he described her unconventional life, cosmopolitan yet condescending treatment of the life abroad which she took to be a playground for wealthy Europeans.

The talk after the 2 papers in the “Turkey” session was wide-ranging and informative. In questioning the first speaker, people were led to talk about the presentation of Turkey and harems in the 18th century, including Montesquieu’s, plays of the 1780s like The Sultan (Lady Mary’s dream that women in the harem can have a will over the men is found here too), Byron’s poems, and Austen’s Persuasion (it was suggested that had the novel been truly worked out and finished it would have explored the power and powerlessness of women).

Mrs Abington as Rozolana in The Sultan by Joshua Reynolds (1732-92)

We had quite a discussion of the veil, and the erasure of women under it, so that they may be killed or beaten and no one will know who might try to help them. I mentioned Orphan Pamuk’s Snow (about suicides among girls in Muslim culture, honor killing and much more), and his very great travel book, Istanbul which I thought the second speaker could profit from reading and looking at too (it’s filled with photographs of the city in the early to mid-20th century).

To sum up, although I had a rich day among friendly courteous people, learned much, I felt I missed at lot because there were too many sessions on against one another. Instead of 4 sessions a day, the BSECS should have tried for at least 5. They also could have started earlier than 1 on Tuesday afternoon. Most people were there by the mid-morning. In the afternoon of the first day, I missed what was probably a highly informative insightful paper on Anne Finch: Yvonne Noble’s “Anne Finch on the Longleat Tapestry.” In the morning of the second I couldn’t get to a paper on Anne Hunter: “Feminism, Lyricism and the Second-Generation Bluestockings.” In the afternoon, I probably should have gone to the session on womens’ letter writing and Ann Yearsley instead of the one on Turkey. I had noticed a possibly original paper on the embodied militias of the mid-Georgian era, but I’ve learned how difficult it is to run from one session to another to hear precisely the paper you want to hear, and once I start in one session and get to know the people and hear the questions and answers I keep hoping the next paper will be better and don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings while they are reading their paper (and wish others would act this way towards me).

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Dear Ellen, I enjoyed reading this – it’s a pity you had to miss on some good papers because of the clashes in terms of time, but it sounds as if you packed in a lot of interest all the same.

Reading about the discussion of Sir Charles Grandison, I’m realising that the part of the book which has really stuck in my mind is the section where he is in Italy, almost like a novel within a novel – he seems far more sympathetic in that part, as he tries to see if he can change his religion in order to marry a woman he thinks he could love and finds he can’t.

Going off at something of a sidetrack, I’ve just realised there is a similarity with the young atheist heroine in Mary Ward’s great (I think) 19th-century novel Helbeck of Bannisdale, who tries to become religious because the man she loves is a Catholic, and just can’t do it – her mind holds out against her heart, so to speak, as Grandison’s does. I do remember that he is annoying as a hero a lot of the time, with all the endless relaying of compliments, and also that the religion gets suffocating – but it’s the Italian part that sticks in my mind.

Sorry not to have been around much this week – I did watch the inauguration on TV here and loved seeing Aretha Franklin sing.

— Judy Jan 24, 4:50pm # - Dear Judy,

Thank you for the comment. I went over to look at all the sessions in the 2008 ASECS and the planned one for the 2009, and, like this BSECS, there is nary a paper that mentions the Italian section of Grandison. Margaret Doody wrote a brilliant paper on “dreams and ruins” in 18th century novels where she discusses the Italian section, and Walter Scott preferred it, but this is nowadays rare. I don't know why it's neglected. I seem to remember it equally with the English parts.

How fascinating that Mary Ward wrote more than one novel on atheism. The other is Richard Ellsmere, no? The story line of a Catholic – Protestant intermarriage is not that uncommon. To us it seems odd that in marriages it was understood the girls would follow the mother and the boys the father, but we find it in Phineas Finn.

I realize how busy everyone is; I have been so too.

Ellen

— Elinor Jan 24, 11:03pm #

commenting closed for this article