Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Assassinating Oneself: On Not Coping with Freedom (_Souffrir_) · 12 December 05

Dear Harriet,

I’ve sent you letters where I do an informal literary analysis of a book I’ve finished. Today I’m sending you summaries and musings on Chantal Thomas’s Souffrir (Paris: Payot, 2004) and Coping with Freedom: Reflections on Ephemeral Happiness (trans. Andrea L. Secara [NY: Algora, 2001]) as an attempt to get a handle on these books. I’ve been so excited, stimulated to thought, refreshed, and just riveted by them, that I want not to forget them. Yet upon finishing them I will not have a sense of what the books adds up to, of what she is saying as a whole—until I write about them.

Thomas’s central thesis in Souffrir is that people today insist on ignoring, effacing, and denying how much they like suffering and choose to suffer—all the while there is pleasure in suffering. She argues that in previous centuries people used religious doctrine as a rationale for allowing themselves to discuss suffering as an experience to value and to praise, and then that modern psychiatry has turned out to be as repressive as the social mores it pretends to explain. In a sense religious thought is presented as humanly kind, productive.

She does not derive her justification and book in praise of suffering from Freudian or religious, but rather from a slew of philosophical books (hers has been a life of rich reading) and observation of everyday phenomena where a choice to suffer or suffering is not openly admitted to—except perhaps through comedy. Along the way, she argues that human imagination seizes on suffering as a way grasping the realities of our human condition (this in art), as a way of apprehending pleasure (though the lens of suffering) and as part of living fully and becoming ourselves.

Her "Introduction" tells we screen ourselves from ourselves, and includes an analysis of Jean Renoir’s La Règle du Jour (pp. 12-22). We interpose manners to shield ourselves from discovering who we are (she quotes Nietzsche on taste as an instinct of self-defense), and she quotes a remarkable exchange where one character exclaims how he is suffering, and the replies, yes, we all see, but we all seem to ride over these things to survive. She analyzed this film to suggest its theme is "il faut apprendre à vivre, enfin" [finally, we must learn how fully to live], and how difficult this is.

But, asks Thomas, is it really necessary to refuse to recognize grief absolutely, deny it, turn it into derision, call it sickness, or to accept it, and "lui donner une place dans nos images et nos désirs" (p. 20). Of what are we so fearful? And are we really keeping what we dread at bay at all? or letting meaninglessness control us? And thus, paradoxically, throwing out pleasure and real gratification with both hands.

Before I count the ways (go over the chapters) of suffering according to Thomas, I want to say that hers is not a book which advocates masochism. I read it because I mean to write an essay on the writings of Sophie Cottin, and want by extension to understand a fundamental type of l’écriture-femme and protest novels, one maligned and derided in our era. Through the suffering character, the pathetic "plainte" in Thomas’s chapter), the author can make visible the ravaging injustices and cruelties practised by the more powerful on the relatively powerless. The problem of the justification is that of Angela Carter’s feminist reading of Sade: even if the narrative allows an exposure of the denigrated, marginalized and hurt, the central characters model suffering ("mysticism") and invite abjection1. How much easier to be a wife ("chiens" in Thomas’s formulatin as so many men have compared their wives to their dogs).

Two powerful chapters in the book ("contrat," "fanaticisme") ridicule and show how shallow and distorting is the framework or understanding psychological writing has placed on the works of Sacher-Masoch and Sade. Thomas tells the real life of this man and the woman he makes the center of his literary contract. She frames his fantasy with the autobiography of Wanda (Confession de ma vie [Suisse: Tchou, 1967]). In life Sacher-Masoch exploited and lived off Wanda, and these dream fantasties were an irrelevant, absurd, and ineffective way he had of keeping the realities of their existence together at bay. Sade and Masoch’s fictions were picked up by Kraft-Ebbing and treated as non-fiction in his vitriolically anti-homosexual normalizing Psychopathia Sexualis; and most writing today is based on reversing the hostility of Kraft-Ebbing’s radically decontextualized accounting of Sacher-Masoch’s work, without ever looking at the woman’s or mens’ life. She provides a similarly iconoclastic persuasive debunking of modern psychoanalytical glorifications of Sade’s work as liberating.

What are the ways in which Thomas shows people choosing to suffer in life much of the time and gaining intensities and power from the experience? Some are banal and I know, Harriet, you don’t need me to elaborate: the abandonment of oneself to erotic enthrallment where the two selves of the doppelganger are discordant, disjunctive, at odds ("abandon," e.g., Elinor and Marianne Dashwood of S&S); the absence of action in a disastrous marriage where the two people remain preying on one another, using the one child they produced for their excuse ("amour"); imprisonment ("bagne," both on the part of those imprisoned and those who imprison them); waiting ("attendre," take the practice of dances where one person must wait for another to come over, or experiences abrasive encounters by coming over); the power of open anger ("rompre [ne pas])"; "séparation"): and modern workalcoholicism ("travail").

I took my header from her section on work ("travail"). Thomas writes that under the pretext of working, they choose to sacrifice the largest part of their lives to an annihilating ennui in exchange for material goods; they refuse to identify with themselves the time they give over to endless work; they don’t see it’s the self they must assassinate to avoid:

"Distinction aveugle qui nous pousse à ne pas voie que c’est soi-même qu’on assassine" (p. 98)

In our work is our salvation takes on a paradoxical ring here. The individual who makes of herself a pariah (say George Eliot) or who presents him or herself as too sick to spend their life at a workplace has much to gain: privacy, time, space, liberty.

In this and other chapters Thomas denies or ignores the few individuals caught up in larger patterns they would choose not to be part of. The large general demand would not persist if a majority of people were against it. People want the anomie of the crowd in the subway.

At the same time she reveals where unacknowledged pleasure and compensation emerge. In solitude and libraries and places of allowed silent imagining ("bibliothèques"): there we have our unalloyed adventures all the while we are (so Sartre has it) "ridicule, pathétique, désésperant," forgetting how that book came to be, its marketplace context, its lies, holding to it as shelter, protection, a country to rest in, "une aventure" which reassures: elle est chaste, tranquille, silencieuse, fermée aux tempêtes" (pp. 67-72). The library is a diary of our lives. What then? If it’s a substitute, "aussi triste que soit un libre, il n’est jamais aussi triste que la vie" (p. 73). In idyllic escape books for children ("livres d’enfance," a basis for books by grown men and women which are also children’s books); in behavior called cracking up ("fêlure") which frees the person from conventional imprisonings, erects a sudden barrier.

I was startled by her chapter on forgetting ("oublier"): in one of his Ramblers Samuel Johnson argues the task of the civilized person is often to practice the art of peace and apparent reconciliation, of acquiescence in rituals of closure (jury trials) through cultivating oblivion. Thomas’s "oublier" finds in the loss of memory I know happened to me from the years 17-19 profound advantage. I am troubled because in the case of these 2 years I cannot call up memories beyond 5. I have to work out what happened by remembering what I knew at age 19-20 and rewinding back to age 16 to work out that X had not happened by that time according to my memories of 16. Thomas says

"la rupture voluntaire avec les ombres de la mémoire est lucide et déséspérée sans doute, mais également tonique, profondément vivante."

To forget safeguards us, and provides a surcharge of "insouciance" which renders possible "une vita nuova" (p. 160).

It will be seen that the mobius strip of this Souffrir includes happiness and the problem of coping with freedom. Thomas’s book on this theme is as iconoclastic. There she opens with delectable activities, those with no practical purpose. She offers an incentive to travel (and I see a chapter on the travelling woman), to living on the fringes, of recording what can happen when one takes time for onself.

Coping with Freedom focuses first on the distrust the generality feels for people who keep themselves apart, and do not marry, do not commit ("going on strike"), and with solitude ("just passing through"). Contrary to much modern American feminism (where women worry about being lost to posterity, having no influence on others, no name to find in a card catalogue in the library), she suggests

"Being in doubt about one’s name offers rich romantic virtualities, and the absence of identity leaves you the possibility of inventing yourself" (p. 30).

And yet both her books fit so suavely into a large number of paradigms easily recognized in women’s novels—and Beatrice Didier’s L’Écriture-femme, to say nothing of powerful protest novels, of which I’ll cite just one intensely masculinist, active-adventure swashbuckling instance, Marcus Clarke’s very great For the Term of his Natural Life (1874, about a man unjustly convicted and transported to Australia for life).

The photo for the cover illustration of Coping with Freedom is a variant on a 19th century archetypal painting of the quintessentially unattached young woman. In front of Thomas’s book we see a very thin young woman in a nondescript simple black dress. She has long straight brown hair. She sits under the shadow of a large oak tree. She is smoking in a cafe; near her is a small table on which we see her glass of wine, purse, book, and small plate of food. We glimpse a forest to her left.

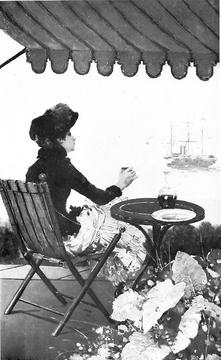

Another variant of this is a reproduced painting in Celestine Dars and Edward Lucie-Smith’s How the Rich Lived: The Painter as Witness, 1870-1914 (London: Paddington Press, 1976):

Jean Béraud (1849-1935), Seaside Café (1884).

We see an elegantly dressed woman alone in a seaside café under an awning which forms an informal sort of proscenium. She has a jug of red wine near her on a small table and is drinking some. A small amount of food (bread roll?) is on a plate near the wine. Flowers and leaves are to the side; the wooden chair looks like the sort of thing one would have at a vacation seaside. She gazes out at the sea and a tall ship in the distance. She’s in a reverie. Lucie-Smith and Celestine Dars describe her as alone, with a sophisticated look on her face would have marked her as "fast." To me both women look intelligent, free bodily, openly sexual, self-possessed, and enjoying the pleasures of life—on their own. They are open to experience, coping with freedom.

Chantal Thomas’s two meditative books on suffering and happiness merge from a peculiarly woman-centered iconclastic point of view, one which takes as given the necessity of making visible the pains and choices on offer, the profound suffering one must work through social forms. In Writing a Woman’s Life Carolyn Heilburn says the lone unmarried woman is herself often overdetermined as a monster of unhappiness, and yet this aloneness, its suffering becomes the basis of insight into a indeterminate labyrinth and is often pictured as sheer insouciant quiet intense self-satisfaction. Thomas talks about the enabled woman’s life, how what enables her (a partner who regards her life story as important as is) doesn’t make for amusing flattering anecdotes and how women are unable claim what really helped them, and life skills that give strength.

By the time I got to the end of Souffrir I began to see that these patterns of suffering were bases for learning how to live. In Coping with Freedom I see how crippling is "a radical sense of insubordination" and strengthening a "sense of liberty" derived from aristocratic (elite in whatever sense) origins. Since I’ve been reading Rousseau’s Julie, ou La Nouvelle Héloïse as propaedeutic to Cottin’s projects, Thomas’s choice early on to bring in Rousseau’s advice on educating girls (break them, restrain them to death) makes me find devastating how 18th century women were so taken in by his educational theories.

Sylvia

1 On the 19th & 20th century protest novel, see James Baldwin’s "Everybody’s Protest Novel," Notes of a Native Son (Boston: Beacon, 1965):13-23. An excellent essay which uses the logic of Angela Carter’s Sadeian Woman: an exercise in cultural history (NY: Penguin, 2201), to argue for the use of the masochistic woman sufferer as a cynosure of protest is R. McClure Smith’s "A Recent Martyr: The Masochistic Aesthetic of Valerie Martin," Contemporary Literature, 37:3 (1996):391-415.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

commenting closed for this article