Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

_New Yorker_ Cartoons: Barbara Shermund _et aliae_ · 18 December 05

My dear Anne,

The New Yorker cartoons by and about women don’t change very much over the decades. Basically a set of stock types can be discerned; these types stand for age-group, probable daily occupation, class niche. This past Wednesday I described some typical cartoons across several decades by Helen Hokinson; she seems to have specialized in the middle-aged pot-bellied do-gooder, interested in arts and politics, essentially sheltered and naive.

I am writing to you today about Barbara Schermund’s pictures. They appear between 1925 and 1944. Sometimes she had 2 cartoons an issue. You were (and perhaps still are) paid per published cartoon. To pay someone this way is to get them drawing and also to get them to accept alteration in order to get published and paid.

Like Marisa Acocella (whose cartoons begin in the 1990s and whose work I will describe in my next letter to you), Schermund presents young women who are presented as attractive, thin (the two go together) and living a rich or ideally active and fulfilled life. Schermund’s young women are not career women; sometimes they are mothers; when they are not and appear as pairs she often draws them sexy. They often look have something glamorous—rich and alluring—about them, either in their clothes, hair, or surroundings.

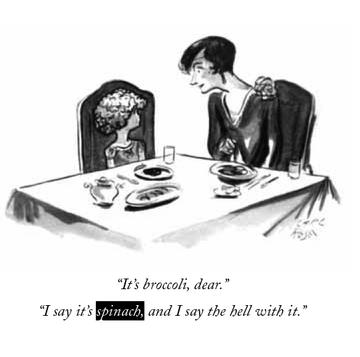

Most people today remember one of the captions of the early 1920s cartoons of the New Yorker. This not by Shermund, but it is typical of the way women were presented in the era and may be by a woman. I begin with it to show the era to which her work belongs. We see a little rich girl with a very elegantly dressed mother sitting over their dinner. Mummy (I can’t help but call her the upper class Anglophilic Mummy) looks down confidingly at her darling and says "It’s broccoli, dear." Little darling looks up and says, "I say it’s spinach and I say the hell with it."

A major battleground of women’s lives sometimes emerges when their children are small. The child early on learns that he or she can gain power (control, time, triumph) by not eating. He or she dares because it’s obvious mother really cares whether he or she eats. And in nature we know instinctively we can skip. The parent who is indulgent or weary and tired may just prepare an alternative dish. So the child gets to control the mother.

What I’ve found angering is the sense I’ve gotten that people despise the woman who doesn’t get her child to eat without anyone seeing how she did it. The woman who takes a child to a restaurant where the child "cuts up," won’t eat is deemed a failure, incompetent. Mother as boss seems to be the underlying notion here. It’s not that people necessarily admire the hard, but they want the convenience of peace and ease. How dare she not make the child behave in a way that suits their convenience? If you’ve ever slapped a child in public, you discover everyone looks at you with disapproval and even shock. But then somehow or other the child is supposed to behave. Shall I spend my life coaxing a child? No thank you. Enact an ideology of domination: that’s even worse.

I’ve seen and experienced women (aunts) who get back or think to prove themselves "mother" by bullying the child mercilessly into eating—beating it even. The latter was my case when young; in reaction I refused to engage in the battle at all: Caroline and Yvette wouldn’t starve; if they didn’t eat this time, they’d eat the next. I did give in by making food they preferred, but if they then didn’t eat that, I threw it out. It interests me that it may be a woman who drew this cartoon and that the caption not the picture itself became famous.

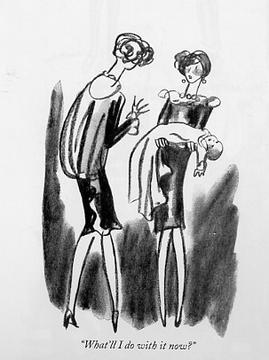

These 1920s cartoons often show women failing to cope with having children. Take this anonymous one:

Babies don’t come with instructions you see. And both women are dressed wholly inappropriately.

Shermund’s style distinguishes her from these others: her women are dressed gorgeously in ways that recall peacocks; she uses extravagant curlicues, serpentine lines, much patterning. The captions show women not interacting with men but with one another or over men or talking with reference to men. Sometimes they are married and talking about husbands, sometimes not. They tend to be depicted as at parties, but we can see them at home, in restaurants and sometimes with children. Here’s one by her from 1927:

Two women with very cartoon like bodies of exaggerated thinness sit on curlicue or basket chairs and a rug with curling serpentine lines or perhaps marble parquet floor. The chairs are drawn to give the effect of thrones; I have seen such chairs and sat in them. There’s an unseen pillow one sits on in the center. Behind them is an enormous potted plant extravagantly drawn to give the effect of feathers, and yet further in the distance columns, one seen in dark lines, the other more dimly shaded. That their hats are dwarfed does not mean they have on small hats. No, even if the effect is dark and discreet and of pancake effect. The impression I get is of a lobby in an elegant hotel. The caption seems to me a dialogue. One says: "My dear I’m just playing at life." The reply: "Got any tricks?"

This, like her others, is utterly feminine in its effect. The chair of the woman to the right which has the haunches puts me in mind of a woman’s hips. I see the two chairs and the way the woman are with their highheels as a "Come hither fuck me" picture where the drawing style is intended to evoke female parts. The columns are the masculine touch. I can’t tell as I haven’t read about this in a while if they are doric, ionic, or corinthian.

The caption undercuts the apparent discretion and elegance of these two women. It also resonates to my ears as irony directed at any notion that life is serious and people who have money deserve respect as having earned it. It’s presents women as succeeding through tricks. This idea of life as a game permeates Schermund’s drawings in the 1920s through the early 30s. Life as a battle.

I like the picture. Its tone is hard.

The cartoons by Schermund in the 1930s do not ignore the depression altogether. We see a repeat of Hokinson’s joke in two women who are watching an apparently abstract ballet and one says to the other, it must have something to do with the coming revolution (words to this effect). They look puzzled. Schermund’s drawings have become a little less extravagant.

Another shows two young women before a mirror. They are dressed to the nines, but the drawing is simple. They look in the mirror and one says to another "Huh! I never saw no ideal man!" I like this one because the notion of an ideal man in fiction puzzles me. One of Trollope’s novels is called Ayala’s Angel and to me the title is cloying, embarrassing (what fool could believe in some angel man: didn’t she observe the men around her as she was growing up?), but the word may be found in other English and American novels. Shermund’s theme is rough disillusionment.

In the 1940s there is more awareness of the war in all the cartoons. Schermund has one cartoon where we see the glamor girls dressed in frocks that only come down to their knees, and much plainer hats. They are outside a series of telephone booths in which we see sailors. One says to the other she’d be hurry home for she may be getting a phone call. Another—unusual—shows an older married woman at her desk writing: the husband sits near a child whom they are trying to coax into bed. Nothing glamorous here at all.

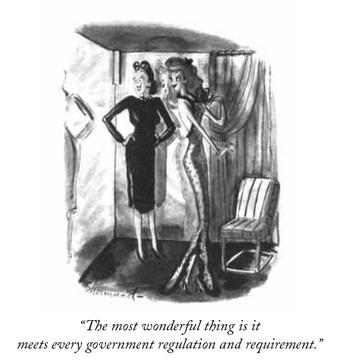

I found this the most characteristic and striking of Barbara Schermund’s in the 1940s. From 1944:

The glamor girl now exists in a war context. As in most of the Schermund’s of younger perhaps unmarried women, the female figures is extravagantly thin. This one has the sexy mermaid body suggested repeatedly: her feet emerge as fins coming out of the tight dress. She is in an expensive shop trying an evening gown on. The caption: "The most wonderful thing is it meets every government regulation and requirement." You must not be seen to be spending luxuriously for yourself. Still the woman’s life still revolves around dressing, and getting a man, and the strong anti-socialistic point of view (against "goverment intervention" as foolish, irrelevant, perhaps counterproductive) is as strong as ever.

Across the eras the cartoons by men and women do lack originality: the woman who keeps portraying women in a lecture hall is doing the same trick or joke over and over again. Barbara Schermund’s types whose lives revolve around men and dresses are still there —though the uncomfortable mother has been replaced by uncomfortable parents.

I’ll end on one woman cartoonist who is idiosyncratic in more than drawing style and whose work spans the second half of the century: Roz Chast. She offers stick figures in colored multibox cartoons. Her typology differs somewhat: she shows frenzied lower middle class men and women. Very desperate and on the edge. She has been drawing for the New Yorker for the last 4 decades. She often has domestic scenes of intense fretfulness, and the words chosen suggest frustration. Sometimes her characters are at home, but when they go shopping or we see any of their paraphernalia (such a cards sent out at Christmas time), we see the same frazzled cri de coeur. She still draws for the New Yorker today: there was a cartoon by her in last week’s issue. I suspect what one is seeing in her case is an unusual inner reflection of her own preoccupations, even if it is repeated and has become formulaic. Alas, I don’t find her cartoons funny; often I just don’t get the joke.

Sophie

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

commenting closed for this article