Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Mary Cassatt at the National Womens' Museum; & womens' landskip art · 16 December 08

Dear Friends,

On Saturday morning, Yvette, the Admiral and I went to two new exhibits at the Women’s National Museum in DC. For one we had a tour group to join with: Jim’s a Columbia Univ alumna and sometimes the affiliate club in DC (of the NYC one) invites alumnae to come and join in on their does. We’ve gone to four thus far; one was a film on Iraq and talk by a reporter; another a tour through an exhibit at another museum in DC (the Philips); one included drinks and talk on the terrace of the

Kennedy Center.

What was wonderful about this tour was the guide-curator, a lead

curator at the museum right now (Ph.D at Columbia) had an interesting talk. She managed to take three rooms of less interesting Cassatts and bring out what was interesting in them even though a number were not her best. She showed how in the mother-child portraits if you look for real you will not see sentimental coy happiness and emblems of stereotypes, but faces of real people who are often bored, restless, have far away looks, and do not project the attitudes that the titles of the paintings suggest. For example, one had a title a mother reading to a child. The mother was reading to herself, and the child clearly wished she were doing something else.

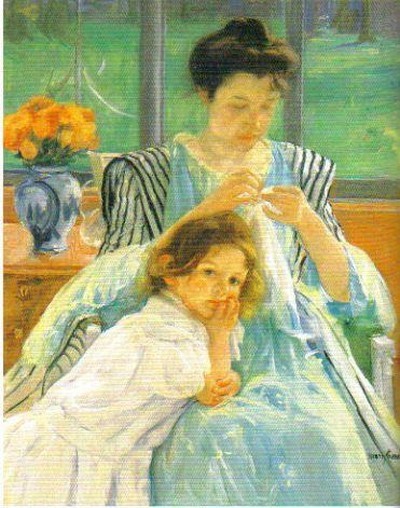

For example, this one which may be titled Young Woman Sewing or Little Girl Leaning on her Mother’s Knee (1901):

Its color is splendid, and on WomenWriters through the Ages we discussed how the two titles are equally apppriate. This curator would call our attention to the expressions on their faces. The woman looks slightly vexed, tired, weary, her hair askew, and the chlid looks out at us, wondering how she can find something to do that’s interesting. The curator would say this undercuts the stereoptype of mother and child.

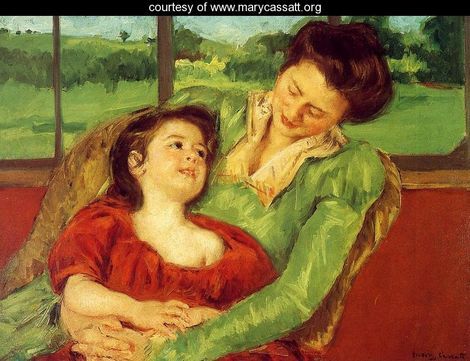

Admittedly not all these dozens of mother-and-child show the pair looking elsewhere: what more loving pair can be found than this (a picture in the exhibit) glorious composition in greens and red:

Margot Before a Window

The suggestion of Renaissance womens’ sleeves, necklines and rich fabrics is deliberate. The painting is intended to evoke memories of paintings of Renaissance women, queens especially and their daughters—and not ironically. Note the little girl’s low neckline.

Beyond mother-and-child portraits the curator showed that Cassatt would deliberately undermine, quietly mock other of the mores of portrait paintings (she would show the rich patron or friends to look absurd in overwrought clothes for example). The curator also thought such paintings were radical substitutes for “important” people and numinous gods and icons in the equivalent earlier paintings and so was an equivalent kind of shock or departure of the type seen in impressionist landscape paintings.

It was then I asked what was the proportion of portraits to landscapes in the later 19th century when the impressionists had broken with norms of celebrating the rich and powerful and landscapes were beginning to gain prestige over history painting.

She replied to my real question. It was really: “Why so many portraits by Cassatt & nothing else?” Why not radical landscapes? She said it was expected women paint portraits. The reason we see such a preponderance of portraits for women painters in the 18th century (Kauffman does mythological figures but otherwise portraits, Vigee-LeBrun all portraits) is except for still-lifes that is what was thought appropriate to women. It was thought they were not imaginative enough for landscapes, and they really did follow these expectations as their landscapes would be critcized or not wanted. It was more than money for Gainsborough (we see) also did landscapes. Women weren’t supposed to do landscapes.

There are very few landscapes by women before the 20th century. While the money was in portraits, and men and women both did portraits, men also did landscapes, for money, prizes and out of a joy of painting landscapes. Analogously women did few history paintings too; there you can find Kauffman entering the field, but by the backdoor of mythology and in her case the stories are all these lugubrious stories of submissive women, erotic and enthralled women or women in poses that are highly sexualized if it’s not overt.

The first wave of landscape painting by women begins with impressionism where like men they were bucking a huge more in favor of painting not just powerful, well-connected famous individuals (as well as artistic ones presented in hierarchical “serious” ways or on stage hieratically) but landscapes owned by people where it was clear that what was celebrated was the control of power.

A small country road on a snowy day with a few people on it (say by Camille Pissarro) is a radical revolution. And women did participate in it, but according to this woman, still if they wanted the dealers to ‘press’ their stuff and supposedly appeal for sure to a larger public what was wanted were mothers-and-daughters, sentiment, portraits and still life flowers and fruits.

Now I know myself women were breaking away from this in English painting somewhat earlier by painting anecdotes of modern domestic life, but have to admit most of those I know as well as tragic scenes of country life begin in the later 19th century. The later ones are not impressionist but emerge from a woman-centered context and women’s favorite genres they invented themselves as they invented genres of poetry they favored and today do womens’ films which are distinctly different in interesting ways from mens’. See Deborah Cherry, Painting Women, e.g.,

Ellen Gosse (1850-1929), Torcosse [corrected to Torcross], Devon (1875-79)

Modern day photo of Torcross (see comment by Clare)

To return to Cassatt, the curator said despite Cassatt’s great wealth (from her family, it came from railroads), she had to please dealers to get attention and to get her work into shows, and they wanted mother-and-children from women painters. So the kind of portraits that predominate are mothers-and-children. I wonder. Cassatt does seem to paint the women and children so lovingly—and she continued this in the Japanese-style flat drawings and watercolors.

She also interestingly implied that Cassatt loved women and talked about her relationships with her housekeeper who she often painted and her models. Hardly anything about sex is ever written down by women in their journals (even unpublished and uncensored apparently) before the mid-20th century, but she did fill out a sense of the woman’s life, also with her female relatives who she also painted.

Perhaps all the mothers-and-children have something to do with her kind of sexuality and a way of imaginative fulfillment for her. At any rate, I felt very enthusiastic about Cassatt after the curator finished. She was herself so full of enthusiasm. Hers is, though, an ambivalent relationship as she more than once said that she ignores the titles of most of Cassatt’s works! Surely, she doesn’t want to see the meaning implied, & from books I’ve read as far as I can tell Cassatt titled them. If Cassatt was a closet lover of women [I can’t use the “l” word as then I’m flooded with spam], her emotions may have led her into precisely this kind of loving picture. Juhasz’s Reading from the Heart, an overtly Sapphic reading of romance centers on the mother-daughter relationship of novels as central, and argues the noble hero is often a mother figure (even Rhett Butler is taking care of Scarlett).

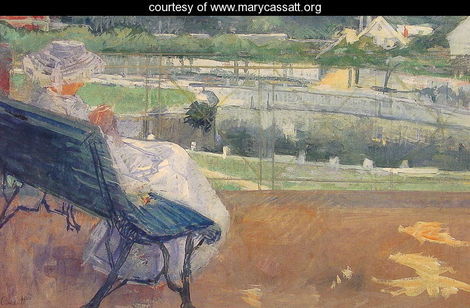

This was not in the show; I include it as a near-landscape:

Lydia on the terrace crocheting

The other show we went to was a photography one which I admit I didn’t care for. So many of the photos seemed cruel or deliberately offensive—not to make a point but to be “in your face.” There was a particularly brutal one of a heavy-set woman with tattooes on her arms breast-feeding a boy; her breasts were huge and she dominated the space utterly. The overt meaning was she was butch, and this was an adopted child. She looked like she was revelling in her power over this very tiny male. I know this is a personal reaction and some might say I am misreading the painting. Still …

Yvette made some good ironic comments: in one attractive landscape a very displeasing picture of a women was put and I said it made me feel how much better the world is without people in it if they are so ugly; to which she replied it makes me think she’ll get many mosquito bites. If she really were standing there, she’d be miserable. I know that this show has been praised (like Wacko was) so will leave my critique at this.

I’ll end this blog on two 18th century “amateur” woman artists’ landscapes. Here is a rare survival of a large finished piece known to be by a woman from the 18th century on our list sometime ago: Amelia Hotham’s River Scene (1783):

Hotham did not make money and hence is not considered a professional but she was an artist of the Claudian school and we see her grasp of Claudian perspectives as well as an English appreciation of subtle effects—it’s lovely, pleasing in its suggestiveness of a place far away, remote, a kind of dream of a quest-adventure of the woman traveller. The buildings seen from on high are subtly and deftly indicated; it’s tactful, and in a softer larger reproduction you can see the bottom is filled with quiet indications of waters in the shadows of rocks and overhanging flora.

Often one has to go to anonymous to find women landskip artists, and we know it’s a woman because the sketch is “by a lady.” If she’s aristocratic, she may dare to put her name down. On our groupsite page for a few days is a “Woodscene” by the Countess Templetown.

There’s a high degree of finish and sureness of composition—the

lady had time, leisure and enough self-esteem.

Women novelists loved to use the landskip scenes they saw in sketch books and reprints of illustrations, and certainly Charlotte Smith was among these. I know of a painting by one Lady Diana Spencer (same name as the princess who self-destructed so catastrophically), View of Windsor (1723) but have never come across the image. There are also know views of Lord Grantham’s park by Lady Amabel Polwarth (c 1765), this from Germaine Greer’s The Obstacle Race. Greer does say that after still lifes, women artists in the 18th century turned to less expensive, more ephemeral forms of visual art: pastel portraits, pen drawings, engravings, water-colors.

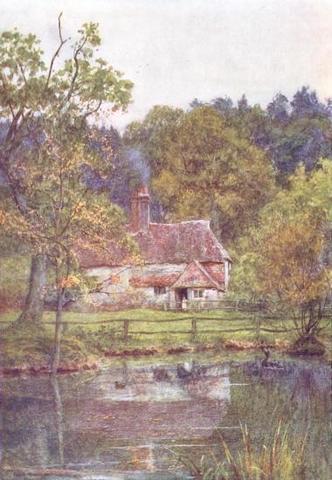

I love landscape art and it seems to me women excel at it, partly because they are often colorists; some of my favorite paintings are landscapes of the later 19th and 20th century by women, e.g., taken purely at random from images of the paintings of

Helen Allingham (1848-1926): Chase Cottage and Pond

Ellen

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Addendum: on another woman painter contemporary with Cassatt:

The TLS commentary for Oct 24, 2008 (which I’ve just now got to) had the most touching sketch of Mary Taubman by Michael Holroyd. A lifelong lover & student of Gwen John's art, she never wrote her book :) It’s on p. 15 of the issue, and another version of the tale is online: a fine gentlewoman scholar of high integrity:

http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/the_tls/article4990906.ece

This summer one of the best books I read (most fondly loved) was a life of Gwen John seen from the margins and through reflections of Margaret Forster’s novel Keeping the World Away. I discussed this in this blog at the time (under “women’s novels to be getting on with”).

E.M.

— Elinor Dec 17, 11:22am # - From Clare:

“Dear Ellen, so nice to see that Mary Cassatt’s paintings were so much more than the chocolate box sentimentality they are often seen as. I really enjoyed the blog.

There's a mention of Ellen Gosse, Edmund's wife. I have his "Father & Son". Her painting is labelled Torcosse, Devon. I wonder if it should be Torcross? Here's a brief description: Torcross is a small village at the southern end of Slapton Sands, a narrow strip of coastal road and shingle beach separating Slapton Ley from Start Bay. It is now well known as the beach where many lives were lost during rehearsals for the D-Day landings in 1944 and there is a memorial tank, which was recovered from the sea. Slapton Ley is freshwater lake forming part of a nature reserve and is popular with bird watchers. Storms frequently cause damage and nearby Hallsands was destroyed by a storm in 1917, with just a few ruined cottages remaining.

[A photo. See blog itself] This is a view across Slapton Ley. What do you think? It's a different angle, and there is a lot of new build, but the hill looks similar to me. I'm interested in Ellen, but can't find much on the web about her.

Clare"

— Elinor Dec 17, 3:38pm # - Thank you so much, Clare, for this kind and informative reply to my blog on the curator’s (I don’t know her name) tour of the exhibition of Mary Cassatt’s art at the National Womens’ Museum. I have put Clare’s photo on the blog itself and corrected the label on the image by Gosee.

Clare asked about Ellen Gosse. Since when I was younger I used to love reading Gosse’s criticism (he was among the first to appreciate Anne Finch’s romantic imaginative poetry), and have read his Father and Son, I was startled to discover his wife was a “person in her own right” as an artist. I learned this in the indispensable Painting Women about 19th century women painters by Deborah Cherry about which I wrote a detailed blog and provided stills from

http://server4.moody.cx/index.php?id=683. 24 May 07, "Deborah Cherry's Painting Women.

At the above, you will find a little life of Ellen Gosse. To me it’s a kind of tragedy, a real loss that this woman never got to develop her talent. I can’t know how she felt about it, but suspect it hurt hard. The acid letter demanding a social identity at the least suggests this. She was “a giving tree” to others and they were willing to use her to the total limit and people today who use women similarly defend this kind of thing vociferously.

Just think Ellen Gosse might have painted as many pictures as Helen Allingham.

I should this blog on Deborah Cherry’s book remains one of my most visited (outside the Austen materials) blog. I included that day what Cherry wrote about Ellen Gosse. There is just about nothing about her on line (not at ODNB except as Gosse’s wife).

Ellen

— Elinor Dec 18, 7:41am # - From Clare:

“Thanks so much for the information on Ellen Gosse. I too have Father & Son, her husband’s book. It relates his life in St. Marychurch, where I live. Many of the places and houses he mentions are still there, however, the chapel his father founded (Plymouth Brethren) is now a knitting wool shop.

Clare”

— Elinor Dec 18, 1:08pm # - Dear Visitors and readers,

You might like to know I eliminated the “l” word about an hour ago. Why?

Over the past week my blog has been inundated, just flooded with huge amounts of spam, all of which were loaded with the most sickening language you don’t want to glance at, pornographic, ugly, mean, whatever words you want to fill in. All of it aimed at this blog. I wrote another on three shows we saw at the National Gallery, none at all about sexual orientation and no such spam came. None of it showed as before any message shown on my blog I have to approve it. I don’t have to read such malacious filth, but it would take time just to delete them.

I reread the blog and realized that whatever word I used would trigger this response from the internet. I would simply have to eliminate the idea. After a while I substituted “loved women,” “not heterosexual” “Sapphic” and “butch” (but I’m aware that I might have to remove butch after a few hours today) so that I could remain in print in public having said that this curator suggested Cassatt was lesbian and the tone and feel and some of the content of her pictures reflects this.

This is a small instance of how to erase people and reality. I’m not giving in; I’ve substituted euphemisms, but admit they look silly (the wording looks hopelessly stilted).

I know things are changing. I saw the most lovely movie about two bisexual women, Happy Go Lucky and wrote a blog on that at the time (3 weeks ago now?). I didn’t realize I never used the “l” word but rather bisexual and so it didn’t get this kind of spam.

Ellen

— Elinor Dec 22, 12:59pm # - From Carol Dorf:

“I’m sorry you had to go through that Ellen.

I saw a similar exhibit of women impressionists in SF last year with my pre-teen daughter, and my 78-year old mother (we loved the exhibit, by the way); but the point is not the exhibit, the point is the presence of malicious anti-l spammers on the web cutting out the opportunity for dialog.”

— Elinor Dec 22, 1:00pm # - Dear Carol,

I could scarcely believe this spam was coming from this word. But after a couple of hours of elimination, the spam has dropped dramatically. How horrible this is.

Ellen

— Elinor Dec 22, 1:36pm # - From Clare:

“That’s pathetic. What a world. Just shows that the internet, like elsewhere doesn’t really have freedom of speech. It’s a pity that what started as a method for academics to exchange information now has this sort of pressure out there.

Clare”

— Elinor Dec 22, 2:00pm #

commenting closed for this article