To WW and Trollope-l

December 27, 2004

Re: Elizabeth Gaskell's "The Grey Woman"

I read this remarkable tale last night.

The story line in brief: a young narrator whose gender remains ambiguous comes to an inn in Germany. He or she is told a story about a painting of a woman, Anna by name. In this ancient picture the woman is beautiful but he is told by the family that it misrepresents the way she looked most of her life. Most of her life she was all grey in looks. She had turned grey with terror. Anna was the great-aunt of the innkeeper's daughter's mother. This mother is found lying on a couch inside the depths of the inn -- not far from the picture. The narrator becomes curious and the innkeeper produces a manuscript. Naturally, a manuscript -- as Umberto Eco's narrator says epigraphically at the opening of The Name of the Rose.

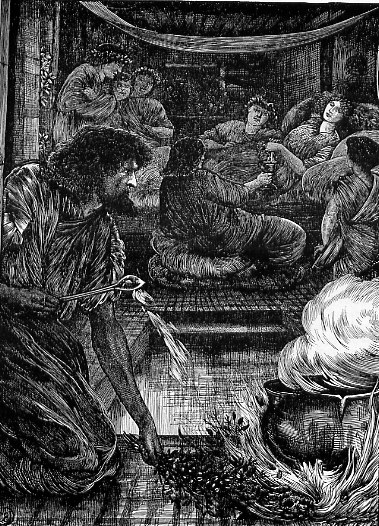

Our narrator vanishes as the manuscript takes over the text. It is mostly told by Anna herself. About one-third into the story Anna tells us of how she came to chose to be married off to a viciously amoral man, M. de Tourvelle, how Anna slowly learnt about his cold selfish possessive nature, became terrified of him just on the basis of his intimidation and isolation of her, and then learnt of his murderous activities at the head of a gang of thieves and thugs. These include murder, probably rape, selling of corpses, terrifying eveyone in the neighborhood to be silent, obey, and fork out money and services. There was a real trade in corpses in London and Edinburgh and elsewhere in the period.

Since I have just read Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Heat and Dust I'd like to say this male, M de Tourvelle, is in type analogous to Olivia's Rawab whom Olivia is drawn into a liaison with; his actual behavior is as criminal and ruthless. Indeed the demon-lover of Jhabvala's book is uncannily like M. de Tourvelle.

Luckily, Anna has been given a maid, Amante, who befriends her and the two run away -- even though Anna is already pregnant. Her pregnancy does not appear to get in her way when it comes to active flight. Most of the narrative is taken up with Amante's and Anna's flight: M. de Tourvelle hunts them down with his men to this place and to that. Gaskell is the heir of Radcliffe here: we have travelling heroinism as well as adventure story.

As we go through this journey we see much violence inflicted on powerless people, and how they are complicit too and submit. There are several parallel incidents in which same subtle attention is paid to the psychology of the people involved as was paid to Anna and her family originally. There is than one nearencounter and discovery. Anna and Amante are saved partly because the husband himself is murdered, but not before he murders the Anna's now beloved friend and companion, Amante.

Their trials remind me of memoirs I've read recently of people fleeing Nazi Germany or Asian countries in the midst of brutal civil wars, of victims in Iran during the 1980s revolution/war with Iraq. Students have told me such real stories themselves. Our two heroines cling to one another in desperate hiding.

Anna does emerge almost unharmed. This is a romance. She has only turned grey. But then I've known women whose hair turned grey in a couple of days: one whose husband suddenly left her with 3 children and never turned up again.

This tale is what is sometimes called female gothic. Pressured young woman, isolated and intimidated young woman, fleeing young woman.

This reminds me of real stories of divorce I know. For example, the opening framing tells of the Anna's difficulty in getting the family to take her in again. They don't recognize her. She has grown so much older, is pregnant. Yet (I suppose this is implied) she is not unchaste; she is someone "risen from the dead." A revenant.

Again while the narrator is a character whose civilized surface and apparent complacency recalls Mr Lockwood, the opening visitor of Wuthering Heights, immediately upon opening the manuscript we and he read a full-throated emotional outburst by Anna to a daughter born to her after her ordeal was over. It's apparent the daughter has not been the ideal loving child or grown woman Anna longed for:

'"Thou does not love thy, child, mother! Thou does not care if her heart is broken! ... And her poor tear-stained face comes between me and everything else. Child! hearts do not break: life is very tough as well as very terrible. But I will not decide for thee. I will tell thee all; and thou shalt bear the burden of choice...."

We do have an intervening narrator. The story is introduced by Anna's daughter who first records her mother's outburst so that we learn she has to make a decision -- either about the mother or something to happen centrally in her life. Anna is telling her story to help the daughter make up her mind. But like the original narrator, the recorder of the story vanishes -- until the last paragraph of the story. Then we are told what Anna's daughter's danger is. I'll withhold that as it turns back on the tale -- recalling DuMaurier's My Cousin Rachel.

The daughter picks up the narrative only for a couple of paragraphs. After the Anna's outburst, she is presented as telling the story of how she turned up at her family's home after her ordeal, and how gradually she was believed to be the missing woman. We then get a long sequence where Anna explains how such a bad marriage could take place and how a woman could find herself isolated and powerless far from her family.

The story is divided into "Portions" instead of chapters. The attempt is to imitate chaos (rather like the kind of thing one finds in Le Fanu's stories to Stevenson's and beyond.) It doesn't quite work as Gaskell connects everything for us. Still each portion starts with a new character.

For example, the second starts with the introduction of the secondary heroine, Amante. It's her tragedy too: she is at first not trusted by Anna. Amante is wary and protecting herself. Anna is led to be afraid to be friends with anyone: "The love I bore to anyone seemed to be a reason for his hating them, and so I went on pitying myself one long dreary afternoon during that absence of his [something frequent] which I have spoken of." But it emerges that Amante is not the moral imbecile such servants are often presented as (there's one in Anthony Trollope's tragic romance novella, _Linda Tressel_ who makes things worse for the heroine and is protecting herself all the time). Amante saves Anna.

Each section is intensely narrated with much chilling effective descriptive detail. The voice is consciously that of a woman at each turn, though a woman on the run with another woman. This makes it differ from "The Old Nurse's Tale:" here we have a story of women's friendship and solidarity. In the ealier famous tale except for the older woman's (the nurse) love for her charge now grown, we have a story of women's desperate betrayal of one another, of their preying on one another in an attempt to "get" the animus male.

The tale is also vampiric. The vampiric male is M. de Tourvelle. What makes it differ from most vampiric tales is it's told from the point of view of the woman sought, the Lucy character and we are given deep sympathy for her. In Stoker's Dracula the woman is suspected, presented as amoral, ruthless, and her sexuality is destroyed by driving a stake through her "heart." Most vampiric tales have at their core a hatred of women's sexuality, a fear and assault on it. Not this. It makes a good contrast to the Jhabvala in its adherence to the woman who is at first lured and then flees. Jhabvala's nameless narrator (coincidentally called Anne in the movie) ends deluded by the religious men and Olivia in purdah, apparently unable and unwilling to return to society. Gaskell's female is not reintegrated for real or totally -- as how can she be -- but her story is told in such as way as to present her allurement with compassion, and to show other women helping and supporting her while in Jhabvala's they make things worse.

When different subgenres of the gothic criss-cross in this way, you have a rich text indeed. Gaskell also emerges as more frank, more thorough, and more sympathetic to women than many a modern woman writer. T

he story is reprinted in A Dark Night's Work and Other Stories: it's also online:

http://www.lang.nagoya-u.ac.jp/~matsuoka/EG-Grey.html

Cheers to all,

Ellen

Date: Mon, 27 Dec 2004

Subject: [Womenwriters] Gaskell's "The Grey Woman"

Reply-To: WomenwritersThroughTheAges@yahoogroups.com

Just a quick note to say many thanks to Ellen for the thoughts on 'The Grey Woman' - I read this story a while ago and it is one of the Gothic tales by Gaskell which sticks in my mind the most. I remember feeling it is influenced by Radcliffe, with the same sort of claustrophobic feeling - but in this story the heroine is forced to marry the violent, abusive man and to live in his power before she escapes.

I keep meaning to read some more of Gaskell's novellas - just about everything is online so it shouldn't be too difficult.

All the best,

Judy

Date: Mon, 03 Jan 2005

Subject: [trollope-l] The Grey Woman

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

It was good to read your enthusiastic post on this short story Ellen. I like your reference to vampire imagery in it, which I'd not seen, but is apt.

I enjoyed it too and thought it interesting that the servant is given such an intelligent and dominant role.

Angela

Subject: [trollope-l] The Grey Woman

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Anna and Amante are two troopers on a very dangerous mission behind enemy lines where getting back to the unit is not less dangerous. Elizabeth Gaskell has written an entirely believable tale of terror: dead bodies are stumbled across "in the trenches"; they must remain hidden; walls of fear seem closing in, and even if the walls stop moving, they are still there.

Richard Mintz

IN response to both Angela and Richard,

Yes the servant is given a central role. At the same time she dies -- and by sheer happenstance. That is part of the meaning of the plot-design and what makes the story a meaningful gothic -- quite apart from the woman's perspective (women's friendships, the mother-and-daughter relationship) that dominates throughout. That death and the framing lifts the tale.

It would make good story matter for a film. But then it's not a "high status" story, is it?

Ellen