A Paper Delivered at an East Central/American Society for Eighteenth Century Studies conference: Civil Conflict in the Eighteenth Century

October 27, 2006, Gettysburg College, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. "Bibliograph, Textual Studies, and Book History, Session I." Chair: Eleanor Shevlin. Panelists : Ellen Moody, William E. Rivers, and John Heins. I publish the paper on this website to provide a preface for an etext edition of Halkett's autobiography and to make the paper widely available, complete with scholarly notes.Cast out from respectability a while:' Anne Murray Halkett's Life in the Manuscripts

by Ellen Moody

. . . reluctant, if the truth be told, to be enrolled in any rank whatsoever, I kept quiet about this adventure. It has been another untold story, though it is better that it should be told. The police protect the respectable, of which I have always been one. So, to find ourselves in this grubby seaside town briefly and mistakenly cast out from respectability a while, and put outside the protection of the law, was, I hope a salutary experience, though not one I would recommend.[1]

At first Simon Couper, an Episcopalian minister officially deprived of his ministry in Dumferline in 1693, as yet the only standard biographer of Anne Murray Halkett (1622/23-99), a 17th century gentlewoman whose life was radically affected by the English civil wars, seems to conclude his moving account of her life in two then conventional ways. He describes an exemplary death:

Some days before her Death she felt most sharp and piercing pains, such; as (she then thought) were more violent than any she had felt in her whole Life, under which she shewed admirable Patience & submission . . . And on Saturday the 22 April. 99. between seven and eight a'Clock at night, she finished her Warfare, and entred into the Joy of her Lord (Couper 53-54).[2]

He then provides a character portrait made up of writing by Halkett herself. For example, she meditated an emblem when she found herself living permanently in Scotland, that her "own State" was that of "a Stranger in a Strange Land, far from her nearest Relatives, and encompassd with difficulties ...." But he then produces something exceptional. He tells the reader that Anne Halkett left a large assemblage of writing, which, we are told,

she caried on with so great Secrecy, that none knew of it; and it was but a few Years before her Death, that she made known, to some, in whom she reposed great confidence, that she had writen such Books; being moved to make the discovery by hearing of several Persons, who died suddenly ... " (Couper 57, 58).

And then for six pages he lists an "astonishing twenty-one folio and quarto manuscript volumes composed between 1644 and the late 1690s, along with 'about thirty stitched Books, some in Folio, some in 4to. most of them of 10 or 12 sheets."[3]

Simon Couper's biography was first and last published in 1701, and since then has been hardly ever read, and rarely studied.[4] The basis of this first paper and one I will give at Atlanta on Halkett's autobiography, is my discovery that in his Life of Lady Halket, Couper anticipates the art of biography as practiced in the later 18th century. Wherever possible he follows Anne Murray Halkett's footsteps, imaginatively journeys through her life with her, empathizes, and relies heavily on her autobiographical papers.[5] His central copy text was Halkett's narrative of her life before it was damaged; he often copies out and paraphrases it closely. His style is readily distinguishable because he writes smoother and grammatically correct sentences, practices symmetry and antithesis, is openly emotional, and draws on sentimental clichs and Biblical archetypes, especially when trying to rouse the reader's admiration or tenderness for his heroine. In the extant manuscript narrative, Halkett's sentences are rhetorical, follow her emotions or enact a scene she is evoking; her tone is guarded, wry, ironic, her endings bitten off or oblique, her style concise, yet detailed and densely compact, and she tends to use the Bible when she needs it to bolster an argument. Thus Couper's biography functions as a palimpsest through which we can view Halkett's autobiography.

In this paper I offer a description of the unpublished manuscript Anne Halkett wrote in 1677/78 before its opening pages; a section early in the narrative, one a little before half-way through, and some final sections were destroyed. How have I managed this? First, by comparing Couper's text with all of Halkett's writing available to me, and checking these materials against relevant contemporary documents. Simon Couper had before him a complete if "discontinuous ... and interrupted form" women's autobiographies frequently take and is familiar to anyone who has read many women's autobiographies as they have been published, or left in manuscript and then published after the autobiographer's death: we first read a lengthy or novella-length more or less coherent narrative which ceases abruptly; this story is framed or rounded out and filled in with many letters and fragmentary diaries by an editor.[6] Together with narrative manuscripts, women autobiographers commonly leave many such letters and fragmentary journals. Using almanacs in order to date her entries accurately,[7] .Halkett had been writing and saving journal entries, letters, and anecdotes all her life; she used these to write and later revise her single coherently-told manuscript narrative, and she continued to maintain and record her daily life regularly, sometimes filling the entries out with devotional meditations, until about ten years before she died..[8]

It is essential to understand that like many other "disjunctive" autobiographies by women, the interruptions and discontinuous nature of Anne Murray Halkett's autobiographical papers do not make them into separate works.[9] I was also able to see where her original manuscript narrative ended, and why it and her other papers manifest their sudden alterations, and what were its actual patterns by comparing her autobiography with women's autobiographies from the 16th through 20th century. Such changes and sudden silences are common in women's autobiographies after the death of someone whose existence the woman writer felt made her existence meaningful or upon whom she strongly relied.[10] Anne Halkett's original manuscript narrative ended abruptly, but the abrupt cessation occurred not (as has often been asserted) in 1654 after she married her second husband, the Scots pro-Stuart landowner, James Halkett (ca. 1600/10-70), but in 1670 shortly after his death, when she woke from a traumatic nightmare to find herself muttering now she was "A Widow indeed!" (S. C. 33-34), a terrifying transference of her memories of her first husband, Joseph Bampfield (1622-1685), to the desolation she felt when she lost her second. Bampfield had, with one small experimental lapse at which Anne Murray had immediately become distraught (Loftis, 29), claimed to have been a widower during Anne and Bampfield's four and one-half year marital relationship.

A second abrupt cessation, signalled by a transformation of the last five pages of Couper's biography, occurred when sometime between 1689 and 1693 Anne ceased adding to her manuscripts continual elaborate diary entries. This was the period when her beloved sister, Elizabeth Murray, Lady Newton, and her only child to survive to adulthood, Robert Halkett, died; afterwards the entries became brief and infrequent. As if to explain this, Couper quotes what Anne wrote at the time of her sister's death: it was "a very sensible stroake, which made a deep wound in her Heart; For, she could well say, that in her she had not only lost a Sister, an only Sister, but a Friend who stuck closer than a Sister." He also copies out her vivid detailed description of her son's last voyage and death and her intensely painful prayer that after this "stroke" God will enable her not to "sin against her own soul" (Couper 48-49). By this time Joseph Bampfield and Anne's beloved close brother, William Murray, through whom she had met Bampfield, were dead (William in 1649). All that was left was to try to settle her own debts, acts which Couper is much concerned his Halkett readers should remember.[11]

I have here to anticipate what's to come in order to explain to readers or listeners who do not know what is the still tabooed matter that partly caused the mutilation of Halkett's manuscript and led to her own equivocations and omissions. Probably in the summer of 1648 Anne Murray was either bethrothed in the present tense, or future tense with consummation, or she went through a private marriage with Joseph Bampfield, variously a soldier, courier, agent and spy on his own behalf and for the Stuarts, Scottish pro-Stuart royalists, Cromwell's government and the Dutch republican leader, John de Witt. The ceremony may have occurred in Holland as Loftis surmizes; at any rate until 1653 Anne Murray lived with and behaved towards Joseph Bampfield as his spouse. Even though Bampfield had not legitimately married Anne Murray because in 1648 his first wife, Catherine Sydenham (who died in 1657), was still living, in Anne Murray's eyes she had become Bampfield's wife. If she had not, she was not just a fallen woman, but an adulteress, a searing stigma that not only would have ruined her prospects in the 17th century, but in print destroy her reputation afterwards. That is why when in 1653 Anne Murray got herself to admit in spoken words she knew Bampfield had another living wife, she delayed three years before marrying James Halkett despite Halkett's manifest eligibility and eagerness to marry her.[12]

Simon Couper describes his text thus: "it is a short Extract, drawn out of large memoires or Diaries, Written by the worthy Lady . . . when she was reviewing the several Periods of her Life" (Couper Preface). As Couper misnames Anne Murray's father and second oldest brother and seems not to have known Anne's sister (Couper 4), he probably never went to London, though from the records of his hitherto undisclosed Jacobite sympathies, he clearly loved his equally Jacobite mistress. Couper copies out the explicit details of her indebtedness from official documents; like Anne Murray Halkett herself and Joseph Bampfield, Couper is adept at telling less than the whole truth without prevarication.[13] He retells his central copy text, the undamaged narrative manuscript, in an abbreviated way. While he often copies and quotes directly, he also paraphrases for concision and to obscure what he thought would damage his lady's reputation or might offend her family. What makes his book so revealing is he consistently kept the space his single short book gave to events and phases in Anne Murray Halkett's life proportionate to the space these took in her original manuscript book until he reached 1670 when the manuscript ceased. We then watch him turn to a series of diary entries, some accompanied with dated devotional meditations, and then copy, condense or, as in her last ten years after her sister's death, elaborate.

I must first counter the "powerfully received image" of Halkett's autobiography since the publications of Nicholls' 1875 and then Loftis's 1979 editions of the censored text as structured around an experience of three erotic romances.[14] A comparison of Couper's text with Anne's manuscript demonstrates the original single narrative and accompanying diairies or autobiographical papers did not take the shape of a pious self-justifying partly secular romantic novel ending in happy marriage.

To begin with, the opening and closing fragments are often inaccurately described. It's true that the one paragraph spared from the original first two pages is devotional (Loftis 9). All else was destroyed. Sara Mendellson 's remark that it's "no accident that three-quarters of the [texts by women that survive are] devotional in nature" is apposite here:[15] The Halkett family preserved the vast sea of Halkett's exemplary meditations, so the strong probability in this case is that something was destroyed because the rest was not devotional. The narrative we have does not end with Anne Murray's marriage to James Halkett, as she immediately goes on to tell of their return journey to Scotland, their visit to Halkett's relatives and her taking on the role of stepmother to his younger daughter, and how, using her Drummond family connections and London friends, she began to network to help her new royalist husband avoid serving in Cromwell's Scottish council (Loftis 86-87).[16]

A proportional comparison of the extant manuscript narrative with Couper's book underlines how distorted is our present conception of Halkett's undamaged manuscript narrative. The 84 page fragment (in Loftis's version) and 107 page novella (in Nichols's edition) that has survived takes up but 29 of 54 pages in Couper's text (pp. 1-29) or 54% of Couper's book. Another 5 of Couper's pages cover the 14 year marriage (pp. 30-35). These 5 pages contain precisely the same mixture of narrative, paraphrase, quotation, and elision that appear in Couper's first 29 pages. So 67% of Couper book represents Halkett's undamaged narrative. The concluding 18 of Couper's pages cover the 29 years Anne Halkett lived on after James Halkett's death (Couper 36-54). Of this 33% of his book, 4 pages or 7% covers the years after her sister's and son's deaths (Couper 50-54). Fourteen of these 18 pages (or the time from 1670 to 1693) differ strikingly from the first 35 pages of Couper's book, which takes us from Anne Murray's birth to Halkett's death, because the mixture of paraphrase, quotation and elision is now calendared, shorter, and discontinuous: Couper after Halkett's death presents events with a date in front of them and without an intervening narrative or events. The last four pages of Couper's book consists of one brief reference to the closing of the school Halkett had opened to support herself (Couper 52), three lengthy anecdotes, one on her longing to participate in communion more frequently (Couper 50-51), and two which recount her efforts to avoid harassment from her debtors (Couper 51-53).

My tentative term for Anne Murray Halkett's life in her manuscripts is collaborative female appeal. Many of its characteristics are described by Caroline Breashears in a paper arguing the appropriateness of this term for many 18th century women's autobiographies; the narrative itself resembles Hortense and Marie Mancini's 17th century memoirs, except the central event is not a flight from a husband, but rather the death of Anne Halkett's mother, Jane Drummond Murray, amid the dissolution of the Stuart order. Halkett's purpose was by writing itself to construct a respected place and roles for herself that made sense of her life among people who used and had needed her but not recorded her public actions because she was a woman.[17]

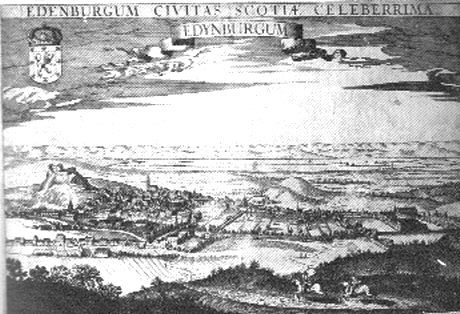

Looking at just her extant manuscript narrative in its present state, Halkett presents herself as partly in flight and partly by choice moving not from man to man, but from woman to woman. Let me trace this trajectory. The first episode, a thwarted courtship, climaxes twice in Anne Murrray's fierce quarrels with her mother. There is then a gap during which Jane Murray died, and we read on to find Anne Murray helping a Colonel Bampfield, her bethrothed, to rescue the young James, Duke of York (April 20, 1648). Where Anne is living is left vague, except that it seems to be London, until shortly after the death of Charles I, she goes to live with her younger brother, William Murray, who has been ejected from court (probably in February 1649) and dies. Since she could have been imprisoned for helping a Stuart heir to escape, she must now flee London so she goes to live for ten months with her friend, Lady Anne Howard in Naworth Castle, Cumberland (September 10, 1649 to June 1650, Loftis 32-50). She is ejected, and, upon receiving Bampfield's letters and advice (Loftis 49), heads further north, Scotland. At Fifeshire the emphasis is on how quickly she is accepted into the household of Lady Mary Seton, Countess of Dunfermline and her niece, Lady Anna Erskin and remains in safety at Fyvie castle with them as their companion for more than two years (September 19, 1650 to June 24, 1652, Loftis 53-63); at the end of this chaotic era brought on by wars, Anne initiates a short touring excursion into Moray, northern Scotland for a month as companion to the niece (June 1652, Loftis 53). Then when Anne choses (in the face of her maid's frightened hysteria, Loftis 62) to travel by herself to go to live in Edinburgh and intrigue with Bampfield on the Stuart's king behalf, the seven months she stayed in, and he hid near, Sir Robert Moray's house are accounted for by presenting herself as a needed companion to the pregnant Lady Sophia Moray (summer 1652 to January 1653, Loftis 66- 69). After Sophia Moray's agonized death in childbirth (January 1653), and Bampfield's desperate flight further north when he was excluded from Charles II's comission to the Scottish royalists conspirators (February 1653), she is driven to less respectable lodgings where she's immediately in danger of molestation. It is then (March 21, 1653) she admits she knows Bampfield's first wife is still living, and after recovery from a fourth psychosomatic illness, presents herself as now governess to and living with James Halkett's daughters (November 1653). Finally, when she goes to London (September 1654), where she's arrested twice for debt, she goes to live with her sister at her brother-in-law's estate (Loftis 79-83) until she marries James Halkett (March 1, 1656), after which her first step is to apply for help from Margaret Boyle, Lady Broghill in Edinburgh (Loftis 87).

In Anne's extant book she presents herself as surviving by becoming a respected and needed companion to a series of titled women. Paul Delany's exasperation with the "tedium" of the long episode at Naworth Castle, and characterization of it as "matter of household intrigue and drawing-room sentiments," "a tempest in a teacup" has often been quoted as just.[18] Halkett writes this episode from later hindsight to show that she made a mistake to entrust a clergyman with the truth that she was married to Bampfield because the clergyman immediately used the information to damage her reputation further (Loftis, 35-36, 39-40). During the episode she takes heart from her sister's husband's attempt to murder Bampfield through the socially-accepted custom of the duel because the brother-in-law's action shows her community her brother-in-law still considers her a respectable woman (Loftis 48-49), but since she has also been told that her sister will not take her in unless she admits Bampfield's wife is living and separates herself from him, now she cannot stay in that friend's house without being insulted and falling further in status. Since she has no money, and her connections were themselves losing their places in the destruction of the Stuart order, she has no where she can go. She chose to believe Bampfield because it was the easiest solution, the most palatable to her pride, and through his employers he could offer her a place with Scots royalist women who were willing to act on their powerful men's belief in Bampfield's honesty.[19] The episode is intended to explain Anne's secrecy and decision to go to Scotland.

It will be seen that I am not underestimating the importance of Anne Murray's sexual and marital experiences. In the extant manuscript narrative, she becomes painfully ill four times, each episode brought on by a reminder she has married a man married to someone else and has not separated herself from him.[20] I am arguing Anne's manuscript narrative and diary entries as well as the autobiographical content of her meditations are not structured as a religious apology or quest for love and husband.[21] She retreats into or presents herself as part of a community of women, except when the occasion arises which allows her to act forcefully as someone who has talents which themselves earn her a respected recognized function in her pro-Stuart community. If we recognize this pattern, using Simon Couper's biography, we are able to understand what the material torn away contained and episodes in the present narrative often ignored or de-emphasized.

It has been assumed the first of the two gaps in the manuscript must have contained either the beginning of Anne Murray's relationship with Joseph Bampfield or her thoughts about Thomas Howard, the aristocratic male heir who, defying her mother, she had allowed to pursue her, and by whose later disregard and marriage to a titled woman she had been humiliated (Loftis 11-22). The void we now face here may well have contained more about Howard and how Anne Murray first met Bampfield, but given Anne Halkett's gift for covering much ground in few words, that one and one-half year go unaccounted for in a part of her manuscript and Couper's book where we are moving from day to day, and the dense matter contained in Couper's text at this point, I suggest she also told in a candid (and apparently unacceptable way) of how she "learned about" and came to practice medicine; how she had other proposals of marriage (one of Couper's sections includes paraphrases of now lost bitter dramatized scene); of Bampfield's friendship with William Murray, her youngest brother, and their work as Charles I's agents; how (this in chronological order) her mother died; she went to live with her oldest brother and his wife; and, very importantly, how, with her maid, she stayed with her brother for "about a Year" only and then lived elsewhere, perhaps in London, or perhaps in Holland, from which time, Couper tells us, "she begins the Date of her greatest Misfortunes" (Couper 12-16).

Couper covers all these subjects and paraphrases Halkett's still favorable description of Bampfield as a moral man where the proportionally somewhat longer now destroyed material in the autobiography would have appeared. Two very long paragraphs in Couper's text at this point climax in Anne Murray's prayer for guidance and soliloquy on her sense of powerless desolation just after her mother's death where Anne cries out: "O leave me not to my self" (August 28, 1647, Couper 15-16). Here where we are told she spent time in public ("the Stage of the world, in a publick Place"), we are also told about a time abroad. Anne Murray endured

all sorts of Tryals, to prove the Constancy of her Mind: Being tossed, as it were between waves and pursued with a constant series of difficulties and incumbrances for the space of fourteen Years, both in England and Holland .. Shipwrack'd & berreaved of all Comforts (except her Vertue and Integrity) . . . (Couper 13)

I suggest that Halkett's emphasis was on her mother's death. She is rare among pre- 20th century women autobiographers for developing and dramatizing frankly the adversarial as well as supportive relationship the two had.[22] Of the childhood anecdotes recounted by Couper, two concern Anne's relationship with her mother: in one she clings to her mother and tries to reason herself out of crying because her mother has gone "abroad" without her; in another her mother is exacting "obedience" coldly (Couper 5). In the manuscript narrative, when Anne Murray is humiliated by Howard's abandonment, she writes "Nothing troubled mee more than my mother's laughing att mee" (Loftis 22). The incident is introduced as exemplifying her disobedience to her mother (Loftis 11), and at its climax she appeals to a male relative to help her go into a Protestant nunnery since her mother will not recognize her except bitterly to reproach her (Loftis 20).[23] It's been assumed the second gap in the present manuscript narrative comes near its original ending, and is wholly about Anne's guilt and remorse over her relationship with Bampfield (Loftis 72). In the place in Couper's biography which corresponds to the gap in Anne's narrative, without mentioning Bampfield again (Bampfield drops out of Couper's story when Anne Murray goes to Scotland), Couper tells of her lengthy praying and fasting for God's guidance so that with a "free and chearful mind she followed the conduct of Divine Providence" in marrying James Halkett, but also her still debt-ridden state and the risks she took as well as pride in living in an Edinburgh lodging and conspiring with the highest-ranking of the Scots royalists conspirators (Couper 26-29). The gap may have contained Anne's grief over the loss of Bampfield and reasons for acknowledging the truth to Halkett, but it also explained why in the next episode, one which immediately follows the gap in the autobiography, she ignored her painful physical illness, and as a Scots royalist risked her life to enable a close supporter of Bampfield, another man anathematized by Charles II, Alexander Lindsay, Lord Balcarres,[24] and his wife, Lady Anna Mackenzie to flee a group of English Parliamentarian soldiers by taking on the task herself of preserving their children and books from harm. The episode as written is a striking revelation of Anne Halkett's desire not only to enact but record her independent actions valued by others and affecting history:

the tide falling to bee betwixt 3 and 4 in the morning, and a very great wind, so as few butt the boatmen and my selfe ventured to goe over, which contributed well, for I landed safe, and was att Belcarese [Balcarres House] before ten a'clocke; and my Lord and Lady [Alexander and his wife, Lady Anna Mackenzie] wentt away imediately, and had desired mee to stay in the howse with the chilldren, and take downe all the bookes, and convey them away to severall places in trunkes to secure them (for my Lord [Balcarres] had a very fine library, butt they intrusted were nott so just as they should have beene, for many of them I heard afterwards were lost) ... as my Lord and Lady [Alexander Lord Balcarres and Lady Anna Mackenzie, Countess of Balcarres] were gone I made locke up the gates, and with the helpe of Logan, who served my Lord [Balcarres], and one of the women, both beeing very trusty, I tooke downe all the bookes, and, putting them in trunkes and chests, sentt them all outt of the howse in the night to the places apointed by my Lord [Balcarres], taking a short way of inventory to know what sort of bookes were sentt to every person ... the things had nott beene two houres outt of the howse when the troope of horse came and asked for my Lord [Balcarres]. There officer came up to mee, and I told him my Lord [Balcarres] had beene long sicke, (which was true enough,) and finding itt inconvenientt to bee so farre from the phisitians, was gone to Edb [Edinburgh] for his health. They searched all the howse, and seeing nothing in itt butt bare walls and weemen and chilldren, they wentt away (Loftis 73).[25]An English point of view and discretion may be partly responsible for how critics have glided over an episode in Scots history, which also reveals that Anne continued to fulfill engagements she committed herself to when attached to Bampfield. Like the puritan women of the period, Anne saw herself as having an important public role to play and unlike many English Royalist titled women, but like her Scottish women friends she played it outside the networking of courts.[26] In the extant manuscript narrative, we have her stories of her nursing the wounded from Dunbar (Loftis 55); her Scarlett O'Hara-like facing down soldiers who came to Fyvie castle while Lady Dunfermline was pregnant (Loftis 58-59); her public debate with Colonel Robert Overton, an intellectual man of genuine integrity and radical political beliefs (Loftis 60-61). Couper tells us of letters Halkett wrote and sent to correspondents on religious controversies about James II's Catholicism in 1685; how she wrote a book intended for publication on how to educate young noblemen in a school, and planned in the 1690s to return home to London to set up practice as a physician (Couper 46, 52).

To conclude, I do not mean to underplay Anne Murray Halkett's lifelong religious trauma. Well after Halkett's death she continues to write on the anniversary of the day she married him that she needs God's help to enable her to "forget the shame of my youth, and the Reproach of my Widow-Hood, if my Maker will be my Husband." Resembling other Stuart women diarists, her "emotional involvement with God" reveals "an erotic transference to have taken place" whereby since she is without any caring significant other, she turns passionately to God.[27] I have not minimized the roles of Joseph Bampfield and James Halkett. In the autobiographical narrative Anne Murray Halkett does not hide from the reader how much she came to depend on and love Joseph Bampfield,[28] and how grateful she was for James Halkett's respect and trust; Couper's biography reveals that she also recorded how much she came to love James Halkett and how she recognized that his death was for her a social and economic catastrophe.[29]

What I have argued is that Anne Murray Halkett's writings about and for her life are not conceived of as a religious apology, proto-romantic novel, nor quest for a destined husband, but a recreation of achieved respectability and respected usefulness in a pro-Stuart royalist order. Margaret Ezell thinks that Halkett prepared her papers for entry into the print culture: it was Halkett who made the archive which includes "Tables of Contents," and two-part titles which identify genres; I noted that at the close of the five devotional books I've seen Halkett included prefaces and postscripts which tell a prospective reader when she wrote the text, the occasion for writing, and textual sources.[30] I see in Halkett's writing a continual struggle to stop those around her from disregarding her, achieve recognition for what she could and did do, make sense of public events (Nicholls 110-11), and barricade herself against memories of disrespectful treatment. In her narrative (Loftis 54) she identifies with Celia in Fletcher's The Humorous Lieutenant.[31] I also found significant her meditations where she identifies with figures in wastelands and small animals. In one such she identified with a small dog "a flock of sheep joined together to assault:"

he avoided them as they pursued. When they encompassed him, he run at them and barked, and so frightened them that they all ran away, and were ready to have leaped over a wall to flee from their supposed danger".

She writes she's teaching herself and her reader "not to be overconfident of one's strength," and "not to provoke every creature as if they were your enemy."[32] In this fable Anne teaches herself not to act on impulses she feels in reaction to her community because survival for her depended on being a respected member of a whole community.[33]

The problem we have when we approach women's autobiographies is we read backwards from memories of conventional 19th and 20th century novels, and the preponderance of devotional material that has been allowed to survive, and do not align them with other women's autobiographies.[34]