Date: Sun, 30 May 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Question on Miss Mackenzie

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

In Miss Mackenzie, very early in the book Miss Mackenzie is twice referred to as a "Mariana":

"A moated grange in the country is bad enough for the life of any Mariana, . . . . ""As far as Margaret was concerned he might as well have ceased to come; and in her heart she sang that song of Mariana's, . . ."

Does anyone know the reference?

Kathy, I enjoyed your story of the librarian who checked books out themselves to keep them from being discarded. Would that there were more like her.

Dagny

Subject: Re: [trollope-l] Question on Miss Mackenzie

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Dear Dagny,

Trollope is probably thinking of Tennyson's poem "Mariana," wherein a lady by that by that name wishes to kill herself. The name "Mariana," according to Tennyson comes from Shakespeare's Measure for Measure, where she is referred to as "Mariana in the moated grange." A "moated grange" is a kind of farmhouse with a ditch around it. In Tennyson's poem the lady keeps saying "I am aweary,aweary, Oh God, that I were dead!"

Sig

Date: Sun, 30 May 2004

Subject: Re: [trollope-l] Question on Miss Mackenzie

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

The notes in the Oxford paperback edition refer us to Tennyson's Mariana as the immediate reference and measure for measure as the original which Mariana retreated to a moated grange when Angelo failed to marry her.

Date: Mon, 31 May 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie: Mariana in the Moated Grange

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

This is not the only novel where Trollope makes use of this analogy. The idea seems to be we have here a woman similarly isolated, similarly depressed (Margaret certainly has low expectations), a type given classical romantic formulation in Tennyson's famous poem. It was well-known, and Trollope and his wife liked to read Tennyson at night.

Here's a copy:

"Mariana in the moated Grange."--Measure for Measure.

WITH blackest moss the flowerplots

Were thickly crusted, one and all,

The rusted nails fell from the knots

That held the peach to the gardenwall.

The broken sheds looked sad and strange,

Unlifted was the clinking latch,

Weeded and worn the ancient thatch

Upon the lonely moated grange.

She only said, "My life is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary;

I would that I were dead!"

Her tears fell with the dews at even,

Her tears fell ere the dews were dried,

She could not look on the sweet heaven,

Either at morn or eventide.

After the flitting of the bats,

When thickest dark did trance the sky,

She drew her casementcurtain by,

And glanced athwart the glooming flats.

She only said, "The night is dreary,

He cometh not," she said:

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

Upon the middle of the night,

Waking she heard the nightfowl crow:

The cock sung out an hour ere light:

From the dark fen the oxen's low

Came to her: without hope of change,

In sleep she seemed to walk forlorn,

Till cold winds woke the grey-eyed morn

About the lonely moated grange.

She only said, "The day is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

About a stonecast from the wall,

A sluice with blackened waters slept,

And o'er it many, round and small,

The clustered marishmosses crept.

Hard by a poplar shook alway,

All silvergreen with gnarled bark,

For leagues no other tree did dark

The level waste, the rounding grey.

She only said, "My life is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

And ever when the moon was low,

And the shrill winds were up an' away,

In the white curtain, to and fro,

She saw the gusty shadow sway.

But when the moon was very low,

And wild winds bound within their cell,

The shadow of the poplar fell

Upon her bed, across her brow.

She only said, "The night is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

All day within the dreamy house,

The doors upon their hinges creaked;

The blue fly sung i' the pane; the mouse

Behind the mouldering wainscot shrieked,

Or from the crevice peer'd about.

Old faces glimmered through the doors,

Old footsteps trod the upper floors,

Old voices called her from without.

She only said, "My life is dreary,

He cometh not," she said;

She said, "I am aweary, aweary,

I would that I were dead!"

The sparrow's chirrup on the roof,

The slow clock ticking, and the sound

Which to the wooing wind aloof

The poplar made, did all confound

Her sense; but most she loathed the hour

When the thickmoted sunbeam lay

Athwart the chambers, and the day

Downsloped was westering in his bower.

Then, said she, "I am very dreary,

He will not come," she said;

She wept, "I am aweary, aweary,

Oh God, that I were dead!"

The intense melancholy and romance imagery contrasts to the dull dense closed in city world Margaret lives in.

Trollope also alludes to Tennyson's similarly high-romance Idylls of the King, e.g., in Eustace Diamonds.

Ellen

Date: Tue, 01 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie - Chapter 1: A Victorian Cinderella

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Although I've noted some scattered thoughts on the list and some very interesting introductory material from Ellen, this is official calendared start of the Miss Mackenzie read.

Before I begin, I must make two disclosures. First, Miss Mackenize is my absolute favorite of all of Trollope's novels and, two, I wish she had ended up with Mr. Rubb. He seemed like a lot more fun. If you read my postings in the future, keep this in mind.

Miss Mackenzie begins our novel as a very human woman and ends up as a sort of paragon of female submission and self-abnegation. I'm not sure where Trollope decided to take that turn but it, unfortunately, doesn't improve the book. The majority of the book however shows a real sympathy for the female mind and some wonderful comic set pieces. Its a romance for those who have already experienced our own romances and know how mundane they can be and still be sweet.

In an earlier post, I termed Miss Mackenzie a Victorian Cinderella and I was gently and politely taken to task for that image. I, however, stand by it. Any single lady in literature, of no means or profession, prior to the 20th century, if not in a singularly lucky position, would have something of the air of a Cinderella. What was Cinderella after all but a very unlucky poor relation who struck it rich? What about our other Victorian Cinderallas? Jane Eyre who begins as a poor relation and strikes it rich when she inherits money from her uncle? Fanny of Mansfield Park who marries the worthy son? I stick by my description of Miss Mackenzie as a Victorian Cinderella - a poor relation, forced to work for her bread, under sad conditions, who, unexpectedly strikes it rich and gains her independence.

Chapter 1 of Miss Mackenzie is very action packed. Trollope uses Chapter 1 to race through the history of the Mackenzie clan, Miss Mackenzie herself and bring her into her considerable monetary inheritance. We learn that Mackenzie pere was a clerk in Somerset House who had three children, Thomas Mackenzie, Walter Mackenzie and, our heroine, Margaret Mackenzie. The Mackenzies consider themselves to be quite elevated by being related to a couple of minor baronets. Mr. Thomas Mackenzie, however, has brought the family reputation down somewhat by daring to go into the oil cloth trade with the lower class Rubbs. Apparently it is not the going into trade that is so bad as the fact that Rubb and Mackenzie has barely "kept their joint commercial head above water." (As a small business owner, I'm going to pause for a moment to savor the absolute rightness of that last statement. Trollope does have such a perfect way of putting things). In other words, if Tom Mackenzie had made money, the shame would have been non-existent.

Another Mackenzie, old Mackenzie as he is referred to, had succeeded in making such a nice sum of money that he had succeeded in getting himself created a baronet. Upon Old Mackenzie's death, he had left a considerable sum to money to both Tom and Walter Mackenzie, a bit over current 1 mil US apiece. The other related baronets, the Balls, then began a three year litigation for possession of this inheritance but they lost. Whereupon Tom Mackenzie proceeded to lose his portion in business ventures and gain a family of seven children.

Walter Mackenzie, on the other hand, became and remained a clerk in Somerset house, never married, hung on to all of his portion of the inheritance and expanded it. After a brief fling in Society, he retired to a life of invalid hood during which he was tended by his sister, and our heroine, Margaret Mackenzie.

Margaret Mackenzie, by the time we have met her, has spent the larger part of her life as a nurse to invalids. She begins her career at age 15 by caring for her father, and upon his death, at age 19, is transferred to her brother Walter's house to nurse him for the next 15 years until he decides to exit stage left.

Poor Margaret is neither beautiful nor clever nor charming, although by her description in the book, her looks might have been more suited to our times than hers. Even so, during the 15 years she nurses her brother, she is given one chance at romance - a clerk from Somerset House called Mr. Harry Handcock. Harry offers for Margaret, Margaret accepts but Walter refuses. At this point, Margaret should have told Walter to take a hike and waltzed out the door with Harry, but they both accept Walter's refusal to consent and Harry turns from suitor to frequent Sunday dinner guest.

But, as I said, after 15 years, when Margaret is between 35 and 36 years old, Walter shuffles off the mortal coil leaving our Miss Mackenzie completely alone in the world with no means of support or prospects. But, circumstances are about to take a turn for the better for our Miss Mackenzie. Brother Walter has left her all of his money, enough to live a very comfortable upper middle class life, a little remembrance for Harry Handcock and the back of his hand to brother Tom, Tom's awful wife and the seven children (for the UK crowd who might be getting confused with slang, "back of the hand" means brother Tom got ZERO.)

Margaret, like a sensible, intelligent woman, perceives that this is her chance to get a little pleasure out of her life. She remains in her brother's lodgings for some months while she decides what she is going to do. During that period, Mr. Handcock decides to wander back into her life with a marriage proposal, sent via letter. Margaret, however (three cheers for Margaret here) decides that if Harry Handcock didn't have the gumption to defy her brother before or come up to scratch after his death, she has no use for him. She decides to take her 800 pounds a year and her newly found independence and move to Littlebath in company with her favorite niece, Susanna, whom she promises to educate. When last we see Miss Mackenzie, for this chapter, she is venturing into the wide world, Susanna in tow, on the way to LittleBath.

Rose Rowland (aka) Sophy

Date: Tue, 1 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie - Chapter 1: Retail Shame

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I think I disagree. The source of the disgrace of the Tom MacKenzies is not especially that they are broke but that Tom is in engaged in selling oil cloth retail. Trollope makes this point gently and with good humor several times. Sir John Ball, for example, (a former political lord mayor, had been in wholesale leather trade and thus respectable even though somewhat broke). Trollope doesn't advocate for that view, but his characters certainly hold it.

While, for me, personally, I dont grok to the distinction, I have to confess that, in my US-based family as recently as the 1920s, the taint of retail was a clear social class marker. Those who sold to the trade or manufactured stuff were proud while those who sold to individuals were ashamed of it (at least according to family lore).

Daniel Millstone

Date: Tue, 1 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie - Chapter 1: Family and Retail Matters

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Sophy's admirable outline of Chapter I does further confuse one issue which is already somewhat confusing. Margaret Mackenzie's second cousin (her father's first cousin), was Sir Thomas Mackenzie of Incharrow, who appears to have descended from a line of baronets. It was her uncle (her mother's brother) who was elevated to the baronetcy as Sir John Ball, and it was his brother, Jonathan Ball, who had left all his money to the two Mackenzie brothers, Tom and Walter. Although we are told that Sir John Ball and his family disputed the will, we are not told why Jonathan had left his substantial fortune to the two Mackenzie brothers. Since they were only his nephews, they could hardly be said to have a better claim than, for instance, his other nephew, Sir John's son, also called John. We do learn more about this later on in the novel, but it would be unfair to give further details at this stage.

On the retail selling of oilcloth, I am inclined to agree with Daniel that it was the retail sale that was bad, and not the oilcloth, or the failure to make money that marked Tom down as a failure. Having come from a long line of retailers, I don't feel any sense of shame, but then I didn't have any baronets or landowners in my family. Trollope , alas, was always a snob about these things.

Regards, Howard

Date: Tue, 1 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Oilcloth shame

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I'm inclined to agree with Sophy that Miss Mackenzie is ashamed of her brother not so much because he trades in oilcloth (though that detail is held up to ridicule again and again) as because he hasn't made a success of it. Maybe she's being ironic, but doesn't she meditate on this at some point in the novel? I think Trollope himself is more snobbish about trade than Miss Mackenzie, though of course she hesitates about offering refreshments to Rubb, Jr., or getting too chummy with hime because she has her position to consider once she inherits money. Our Margaret Mackenzie seems to believe that money has elevated her class (as does everyone else in the book).

Kathy Curtin

Date: Tue, 1 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Getting Trollope titles in Oxford

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I am ashamed to say that I am still waiting for my copy of Miss Mackenzie from Amazon.co.uk - although ordered in April. You would have thought that a Print-on-demand edition should be a reasonable certainty, but no. All other UK options looked rather expensive. I haven't been able to find an online text.

So today I went to the Oxford public library. The catalogue lists 164 items by Anthony Trollope, including Miss Mackenzie and the video of The Pallisers, and 16 titles about him. However, none of these except the video were available off the shelves; all have to to be ordered from central storage, which means a delay of about a week. It also means a charge of about $1, though this was waived this day to honour the 150th birthday of public libraries in Oxford.

The majority the other titles I have acquired over the past 12 months, the six in the Barchester series and the Palliser novels, have been available second hand, though we no longer have much in the way of second-hand bookshops here. You just have to pick things up when you see them.

Be with you as soon as I can.

Martin

Date: Wed, 02 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie - Chapter 2

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I have now had a chance to read the responses to my summary of Miss Mackenzie, Chapter 1. I am eternally indebted to Howard for clearing up the matter of where the Mackenzie brothers got their money. In my defense, I was trying to cover a lot of material quickly and I was afraid if I went into too much detail, heads would be hitting computers in snooze mode across the US and UK.

As for the retail vs. wholesale argument, my assertion that Tom's shame lay not in going into business but in going into business and then doing poorly, I refer you to Trollope and the feelings of Walter, to wit "The blood of the Mackenzies was, according to his way of thinking, very pure blood indeed; and he had felt strongly that his brother had disgraced the family by connecting himself with that man Rubb . . . . He had felt this the more strongly, seeing that 'Rubb and Mackenzie' had not done any great things in their trade . . . They had never been bankrupt, and that, perhaps, for some years was all that could be said. If a Mackenzie did go into trade, he should, at any rate, have done better than this. . . " And that is my and AT's last word on the subject.

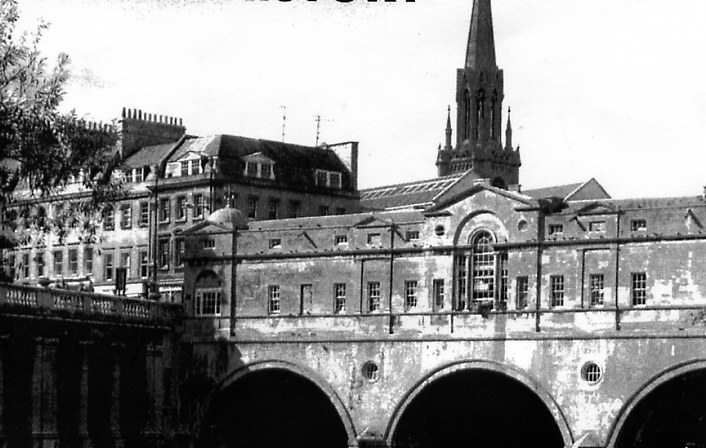

We now rejoin Miss Mackenzie at the beginning of her foray into the world at large. Miss Mackenzie, not knowing exactly what to do with herself and her money, drifts into a scheme to go live at LittleBath, a resort similar to Bath I am told. Miss Mackenzie had become ill after Walter's death and is advised by her solicitious doctor to take the waters of LittleBath. (If its anything like the water my Russian friend once brought me from a Russian spring, I wouldn't travel across the street for it much less several miles.) So Miss Mackenzie gets an introduction from her doctor to a LittleBath doctor, her minister to a LittleBath minister and, thus prepared, ventures out of the wilds of London.

Before Miss Mackenzie heads off to her new life, she is re- introduced to the family aristocracy. She writes to Sir Walter Mackenzie of Incharrow and Sir John Ball to advise them of the death of her brother Walter. A letter comes from the Incharrow Mackenzies advising Margaret that they will meet up with her when they come to London in the Spring. Keep that date in mind - it becomes important later. Sir JOhn Ball, of the Litigious Balls, comes to call upon Margaret in person and makes family peace with her and her money. She is invited to come to the Ball's grand house, the Cedars, for a day and a night to visit with Sir and Lady Ball, their son and their numerous grandchildren. Margaret finds both the house and the Ball family to be grand but rather dilapidated and declines to stop with them for longer.

Having shaken the dust of both Arundel Street and the Cedars from her feet (probably, literally, considering the condition of both those places) Miss Mackenzie journeys to LittleBath and takes advantage of the letter to the LittleBath doctor, Dr. Pottinger, to help her find a lovely apartment in the Paragon. This must be a UK thing - I can barely get my doctor to give me an appointment much less get him to take me apartment hunting. The Paragon is a grand, and clean, upper middle class lodging house which is several steps up from Miss Mackenzie's previous home and has plenty of room her, her niece Susanna and her new maidservant of whom Margaret is somewhat afraid. The price is within Miss Mackenzie's means and the Paragon is even free of . . .. well, we don't exactly find out what the Paragon is free of but just the mention of it is apparently enough to send the landlady, Mrs. Richards, into an energetic fit of denial. (I've always assumed it was bugs but it could be bats for all I know.)

Dr. Pottinger, although rather disappointed by Miss Mackenzie's apparent good health, continues to be a good guide and informs her that the assembly rooms are close to the Paragon. Here, I need help. I have seen the assembly rooms in Bath but, here, the description doesn't seem to apply to the type of room where parties are held but more a sort of gaming club. Any clarification would be appreciated. If it was a type of gaming club that might explain why the Stumfoldians thought it so wicked. But, I'm getting ahead of myself. Dr. Pottinger also points out the location of the nearest churches and, upon hearing that Miss Mackenzie has a letter of introduction to the Rev. Stumfold, drops the assembly rooms immediately.

It's hard to tell here if Trollope likes or dislikes Stumfold. Stumfold is described as "as a shining light at LittleBath" and is rather sympathetically described. He seems like a strict, religious but, all in all, rather pleasant sort of man. The description reminds me very much of one of our US televangelists, Jerry Falwell, who seems rather frightening until you hear him up close and, then, even if you violently disagree with him, he is so amiable and reasonable seeming that you like him anyway. Mr. Stumfold, while forbidding a lot of pleasant things, is smart enough to allow a few of the more innocent pleasures to his people. Not for him, the vale of tears.

Miss Mackenzie, knowing neither of the wickedness of the assembly rooms nor the bright light of Mr. Stumfold, asks Dr. Pottinger how to go about sampling both. Dr. Pottinger conveys Miss Mackenzie's confusion to his wife, who, very succiently says, "What! go to the assembly rooms and sit under Mr. Stumfold? ... She can never do both, you know."

Miss Mackenzie, having secured her Paragon lodgings, now travels back to London to collect her teenage niece and her belongings. Mrs. Mackenzie brings Susanna to Miss Mackenzie's lodgings and proceeds to hand Susanna over in a manner that intimates that she thinks Miss Mackenzie is liable to chop Susanna up and eat her for dinner. The awful Mrs. Mackenzie makes a frightful scene guaranteed to cause any sensible child to think she had been given up to an ogre for boiling. Luckily, Margaret manages to hold her temper and after the mother exits, she is able to reassure Susanna and make her feel welcome. The next morning Tom Mackenzie comes to take Margaret and Susanna to the train to LittleBath and asks if Margaret will be coming to London much. To which she replies, in effect, that as she doesn't know anyone in London or LittleBath, she'll probably just stay in LittleBath.

Susanna and Miss Mackenzie board the train to LittleBath. Now that Margaret is actually on her way, the doubts are starting. She has never had the charge of a house or money. There's a wonderful line here by the way. "No power of the purse had been with her - none of that power which belongs legitimately to a wife because a wife is a partner in the business." This is one of those lines in which AT is revealing something about the time in which he lived which we would not generally be aware of. When we feminists think of Victorian times, I don't think we think of husbands seeings wives as partners in the marriage. But, here it is. But, as we have said, Margaret had never done as much as run a quiet house and here she is, setting out in the world, on her own, in charge of a teenager. And here AT shows a bit of admiration for Margaret. As he points out, Margaret could have stayed and lived a quiet life with her brother Tom or nursed herself or sought the guardianship of some clergyman but, instead, she has decided to venture out into the world on her own to see what she can find. Considering her lack of experience, this took an immense amount of guts. She has "destroyed her youthful verses" and decided to see the world. My personal take on the destruction of these verses is that it is a freeing act. She no longer has to pretend to live. She, now, has the chance to actually live.

Rose Rowland

Date: Wed, 2 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie - Chapter 2: Evangelicals in Trollope

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

The Stumfoldian sections introduce the recurring hostile picture of evangelicals, the low church. While I don't see much record of trollope as a quasi roman puseyite, the high churchniks always come off well in his works and the low churchniks and dissenters mostly badly. How come?

I also don't understand of the assembly rooms.

Daniel Millstone

Date: Wed, 2 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Humor in Miss M

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I, too, find Miss M a funny book. I've read it several times, and I am now listening to the marvelous Donalda Peters reading the book on tape. Listening to the book brings out more of the humor.

I find this book "Austen-ish." Forgive me, but I know another poster mentioned Fanny Price. (Was that Sophy.) There several Aunt Norris like figures in this book as well.

There is understated (Austen) humor in this book, and there is very broad humor as well.

As for John Ball, I think Trollope went out of his way to create the dullest character ever when he created the fellow.

But naughty me, skipping ahead!

Catherine Crean

Date: Wed, 02 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie: LittleBath & Castes: Bath in the 19th Century

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Dear All,

I know something about Bath partly out of my Austen studies. I did sign a contract to write a book to be called Jane Austen and Bath, and, while I never wrote the book, I did a good deal of research which I turned into an essay review on a book on Bath by Peter Borsay.

An assembly room is just what the word says: a place to assemble. You can read about typical activities in them by reading Northanger Abbey. Mostly they were places where the elite met (assembled), and typical that meant dancing. There would be a huge room which on the nights the room in question were opened would be jam packed with "visitors" and local gentry. There would be small side rooms for cards and also refreshments. Speaking generally heavy gambling was not done in these places. You had a Master of Ceremonies; this was someone picked to keep everything in harmony and allow no fights. The most famous of these was Nashe.

The basic point Trollope is making is that what's going on in the assembly rooms in LittleBath is basically innocent. It's the fanatical puritanism of the Stumfoldians and their desire to control their sects that makes them declare the place off limits. When Margaret Mackenzie caves in to the Stumfoldians, she shows that people tend to stay with those who welcome them and those with whom they have been comfortable. Miss Mackenzie knows no one in LittleBath. Such places were not unfriendly, but it helped to come from a family which was known, reasonably connected, genuine gentry or pseudo-gentry. Margaret's family is below this -- though not the relatives who take her in at the end. But she has not been able to cultivate anyone given her position as her brother's nurse and her brothers' both working for a living (gasp) and not in a profession (like clergy, naval, law). She may have the courage to come to LittleBath, but not to go into places among people without some previous connection. When Catherine Morland goes to Bath, slowly she makes friends, but it's hard, and she has the determined Allens to accompany her; she's young and Mr Allen has connections. When Anne Elliot (Persuasion) goes to Bath, her father is a baronet and naturally has connections, friends.

Not only does Trollope show us how difficult it is for people to break into societies, but Miss Mackenzie's decision for LittleBath is not that good. Trollope is a bit wry about this foregone decision and suggests that maybe it was not the best. This is because LittleBath was one of those nearby communities which grew up around Bath and was cheaper. By the first decade of the 19th century Bath itself became a haven for older people living on limited incomes; they came for health. The hey-day of Bath as a center for culture and high life was mid-18th century Bath and we are talking about Bath (Queen Square, Royal Crescent, the Parades, Spring Gardens). Miss Mackenzie is careful and shows her hesitancy and desire not to over spend by going to LittleBath, but she meets precisely the kind of narrow people she dreams of fleeing.

This is not the only novel where Trollope presents LittleBath. He shows us the same community in The Bertrams. Life is petty games at cards, backbiting and assembling in the assembly for the characters in The Bertrams. In Miss Mackenzie Trollope also has the target of evangelical fundamentalism to get at (as in Rachel Ray).

If anyone is interested I could find some titles on books on Bath to cite. There's a library available on Bath and its environs.

The final destruction of Miss Mackenzie's poems occurs later -- much later after a miserable wretched time with all three suitors. This early rejection of her papers leaves many intact and think the scene is approved of by Trollope and yet seen as a gesture of despair.

In this chapter she is someone beating her head against a wall of egoistic narrow domineering human nature. You're with us or against us. Miss Todd is a rare spirit who does not give in but she too has nowhere to turn much.

The one bright moment is Susanna; the only kind person in sight and feel for good human feeling in Margaret herself whom Susanna learns to appreciate. Margaret has some qualities rare in human communities.

If Rose wishes Miss Mackenzie had ended up with Mr Rudd, that is a reading against the grain. Trollope does all he can to make us understand this would be in his and his world's and he expects his readers' eyes an unfortunate decision which would in the end make Miss Mackenzie unhappy because she would go down in the world. We see in these chapters that she is much concerned to keep her place in the hierarchy insofar as she has one. I like Mr Rudd and agree that by the end of the novel Trollope means us to like him (although he can cheat and lie and is more than a little dumb, and might not be very good at holding onto money). I agree he's one of the more good-natured characters we meet (but then there are so few about). But Trollope does not mean us to think a marriage between Margaret and Mr Rudd would have been successful. Curious this because for all Margaret is said to have spent time doing life-writing and verse, she is not shown to read or have any intellectual or cultured interests. This is typical of Trollope's depiction of women gentry, and I have wondered if he does this in order to keep all his female readers comfortable lest they don't read or have such cultured interests (he doesn't want to arouse any envy or alienation is my point). Yet by keeping Miss Mackenzie so blank (as it were) it's not all that credible that she would find Mr Rubb so wanting. We're supposed to believe it's his unhappy taste in colors in gloves. Yes caste arrogance here, but one Trollope assumes has ontological real meaning.

Ellen

Date: Wed, 2 Jun 2004

Subject: Re: [trollope-l] General Babblings on the Comedy

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I'm getting a lot of laughs out of Miss Mackenzie, though I have nothing profound to say about the 192 pages I've read. Thank God for comedy! Eliot's Romola, though stylistically exquisitie, was so heavy and earnest; Trollope's breeziness makes a contrast. Two of Miss Mackezie's three suitors, Mr. Rubb and Mr. Maguire, make me laugh. But Mr. Ball, the gentleman, is not laughable, is he, even though he's bald. He's the most dignified of the three. Tsk, tsk. Trollope IS class-conscious, isn't he? Oh, if he only knew that a raw midwestern woman of the prairie like me was reading his book...

Sorry if I've posted on material that isn't on our schedule. I think I may have jumped the gun.

Kathy

Date: Thu, 03 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie - Chapter 3

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I've read all of the posts to date and, frankly, some of you are not playing cricket. I know its a short book but no fair commenting ahead. Throwing in Ball, Rubb and Macquire at this point is like throwing in Rochester's mad wife before Jane has a chance to make her first trip to Thornfield. Tsk Tsk and a figurative closing of the book on various fingers.

In the opening of Chapter 3, Miss Mackenzie and Susanna have settled in LittleBath and Susanna has started to school. Incidentially, is it or was it normal for girls in private (public - I always get this mixed up) school to be in school till 7 p.m.? It says here that Miss Mackenzie was very much on her own because Susanna left after breakfast, returned home in the summer at 8 p.m. and went to church with the other girls on Sunday.

Anyway, Miss Mackenzie settles into her rooms at the Paragon and receives three visitors over the course of two weeks. The first is the Doctor's wife, Mrs. Pottinger, who acts as the local Littlebath version of the Welcome Wagon. Dr. Stumfold, to whom Miss Mackenzie has a letter of introduction, shows up next and makes himself quite pleasant and entices our Margaret to attend his church. Stumfold's good impression on Margaret is almost immediately spoiled by the horrible impression made by his wife. Trollope trots out Mrs. Proudie once again for good measure and renames her Mrs. Stumfold. However, if you've read the Barchester series, you've met Mrs. Stumfold. Enough said. There is, however, one saving grace of this meeting. Mrs. Stumfold has brought along a nice older single lady named Miss Baker with whom Margaret feels an instant rapport. Miss Baker has fallen away from the sinners to the saints and is now in thrall to the Stumfoldians and an object of pity to her old friends.

Miss Baker does have a slight bit of starch left in her spine and, before she leaves, tells Miss Mackenzie that her friend, Miss Todd, has asked to call on her. Mrs. Stumfold is quite digusted at the idea of Miss Todd and stumps away.

Miss Mackenzie, however, is up for new experiences and waits restlessly for the appearance of Miss Todd. When Miss Todd appears, she turns out to be one of the maiden English ladies we Americans are so awed by. I picture her, Miss Todd I mean, striding across LittleBath in sensible shoes and a ugly hat, running everyone's business and being the life of any party - a "good sort." I once read that Miss Todd was based on someone AT knew but I can't remember whom. Anyone who can remember whom Miss Todd is based on, feel free to chime in. Miss Todd calls and makes herself quite at home and gives Margaret quite another picture of the Stumfoldians. She sets Margaret straight on the fact that, in LittleBath, Margaret can either hang with the sinners or dine with saints but not both. Margaret is preplexed - she's not ready to enter the Stumfold nunnery but she's too nervous to take up a life of dissipation in earnest. Miss Todd says that she will be happy to see Margaret at any time but that if Margaret is going to take up with the Stumfoldians, that she, Margaret, should proabably drop any idea of making Miss Todd her friend. However, even Miss TOdd doesn't go to the assembly rooms. Miss Todd leaves, leaving Margaret more confused than ever about how to go on.

Soon after this, Margaret receives two letters of import. One is a invitation to take tea at Mrs. Stumfold's, which she accepts, and the other is a letter from her brother asking for a loan. The loan is to be made to purchase the premises in which Rubb & Mackenzie have their oilcloth business and Margaret is to be given a 5% mortgage for her money. Margaret writes to her lawyers to see if they think this is a good investment.

Enter, stage right, Mr. Samuel Rubb, Jr. of the silver tongue. Mr. Rubb, Jr., when he appears, is a bit more of gentleman and much handsomer than Margaret had anticipated. He is a nice looking, tall man of about 40. Mr. Rubb proceeds to paint the requested loan in such glorious colors that, by the end, Margaret is panting to hand over some of her money. After talking her around in this fashion, Mr. Rubb drops business and begins to engage in social chit-chat. Miss Mackenzie finds this somewhat irritating. Should a "lady" such as herself be talking to a lowly, retail (I threw that in for the retail crowd) tradesman like Mr. Rubb? Mr. Rubb reveals that he was originally destined for greater things than the oilcloth business but, fate, alas, robbed him of his potential business glory. Mr. Rubb manages to talk his way through another hour at the end of which Miss Mackenzie finally stirs herself to offer the poor man some wine and a biscuit (he's probably quite thristy after all the fast talking he has had to do.) He gets up to leave, finally, and tells her that he plans to be stopping in the neigborhood for a couple of days.

Mr. Rubb leaves and Margaret does some more thinking about Mr. Rubb and her position, as a lady, vis a vis him and also about the mortgage. At the end, she writes a letter to her lawyer, begging him to set up the mortgage, and then dresses to go out to tea at Ms. Stumfold's. This is Miss Mackenzie's first venture into society - the first party on which the invitation had actually come on a card!

Rose Rowland

Date: Thu, 3 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie - Chapter 3: LittleBath as Cheltenham

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Firstly, I entirely support Sophy in her complaints about reading ahead.

While I have probably been guilty of this crime to some extent, I do think

that we are discussing the novel as we read it, and it is unfair to people

who are reading it for the first time if we confuse them by introducing

characters who have not yet been brought into the action by Trollope. I

could take issue with Sophy for her cricketing metaphor, but I will spare

her because she lives on the wrong side of the Atlantic. According to Michael Sadleir, Miss Todd was based on Frances Power Cobbe, 'a

fat jolly lady who was prominent as a humanitarian and an

anti-vivisectionist'. I had not heard of her previously, but a quick

internet search produces about 1700 entries, of which

http://www.pinn.net/~sunshine/whm2001/cobbe.html will probably tell you all

you want to know. Although the attached entry shows her as having been

Anglo-Irish, a number of the other entries suggests that she was an

American. I have not gone into this in any detail to find out which seems to

be right. Apart from the jolliness, there does not appear to be much

similarity to Miss Sally Todd. Miss Cobbe seems to have had less money, but

a great deal more going for her in the way of what Trollope would probably

have called advanced ideas.

Littlebath is generally assumed to be based on Cheltenham, rather than on

Bath. Mullen, in The Penguin Companion to Trollope, devotes a full page to

Cheltenham, and makes it clear that 'Nowhere else in his fiction is a

dislike so vitriolic'. He and Rose had lived for several months in

Cheltenham in 1852 and 1853, when they lived at No 5, Paragon Buildings, in

the terrace where Miss Mackenzie took lodgings, and where , in Mr

Scarborough's Family, Harry Annesley visited Florence Mountjoy. The Rector

of Cheltenham was the Reverend Francis Close, who had great power in the

town, and helped to make it a centre for Evangelicals. Mullen suggests that

Close must have insulted Trollope or his wife and sons in some way to

explain his evident dislike. While it might have been thought that Trollope

was depicting him in Mr Stumfold, Mullen suggests that a reference to a Dr

Snort, who is supposed to have received many pairs of slippers from lady

members of his congregation, is a reference to the Rev. Close.

Ellen's account of assembly rooms gives an excellent summary of them. While

card playing undoubtedly formed a part of their activities, there I do not

think that there has ever been a suggestion in eighteenth and nineteenth

century literature that they were dens of iniquity. Trollope was clearly

using the Stumfoldians' condemnation of the assembly rooms as a depiction of

their narrow-mindedness.

Regards, Howard

Date: Thu, 3 Jun 2004 In a message dated 6/2/2004 10:41:16 PM Eastern Daylight Time,

rose@bashasys.com writes:

Perhaps people were going to Littlebath to reinvent themselves, as they used

go to Australia, or the us, or nowadays to NYC. Certainly MM is reinventing

herself, albeit in a somewhat unimaginative way.

Daniel Millstone

Date: Thu, 3 Jun 2004 I had never before heard of Frances Power Cobb. The few web items I've found

dont ring a bell, in my ear, w/ Miss Todd. Cobb opposed marriage; but, while

Todd isnt married, she doesnt oppose it. Was Cobb such a recognizeble figure

that the brief sketch of miss todd would make her identifiable to AT's readers

or to savvy insiders?

Daniel Millstone

Re: Miss Mackenzie: Miss Todd as a Great Comic Character

I love Miss Todd, one of the great comic characters of this novel. She's so

laid-back and straightforward, so obviously uninterested in the boring

Stumfoldians. For some unknown reason I kept thinking of Peggoty in David

Copperfield every time she spoke.

Kathy

Date: Thu, 3 Jun 2004 Catherine Crean wrote:

Yes, I think so, too, Catherine. Personally, I pine for Mr. Rubb's yellow

gloves. I'd love to have yellow bicycling gloves, but the blasted things only

come in black.

Ouch! Did that book (probably the folio edition, not my paperback Dover)

slam on my hands again, or did I get sent to the corner this time? I'm sorry,

everybody. I promise to stick to the syllabus from now on. I just wanted to

respond to witty Catherine here.

And, yes, this book reminds me very much of Austen.

Kathy

Date: Fri, 4 Jun 2004 It seems to me Mr. Stumfold, well known though he may be in littlebath and

beyond, is dependant financially on his wife's father, Mr. Peters (the attorney

of past sharp practices), lives in the Peters house, etc. Didn't evangelicals

get livings too? Even those tent meeting circuit riders got the proceeds of

collections.

Certainly this contrasts w/ the Proudie's circumstances where Mrs. P's status

comes from her husbands position as does her house, her food and her clerical

supporters.

Daniel Millstone

Date: Sun, 06 Jun 2004 My apologies for the delay in getting up my summaries on 4 and 5 but

I took a rather nasty fall on Thursday and haven't been feeling too

well. I'm up and about again today and ready to move on

When last we left Miss Mackenzie, she had just finished writing a

letter to her lawyer begging that he arrange to loan some of her

money to her brother and has set off for her first foray into local

society, Tea at the Stumfolds. Ellen, earlier, made an excellent

point about why Miss Mackenzie falls in with the very type of narrow

people she is trying to leave. We tend to stay where we feel

comfortable and safe. Having made her foray into the world, she

is now searching for safe harbor and the Stumfoldians have put out

the lighthouse lantern before anyone else. Out of sheer boredom, she

had paid a return visit to jolly Miss Todd, who was not at home, and

left a card. Now she is worried that Mrs. Stumfold will find out

that Margaret has had converse with the wicked Miss Todd. Trollope

does a nice bit here with Margaret's unworldiness. She didn't return

Miss Baker's visit, whom she liked very well, because she wasn't

sure it was proper to visit a lady who had only come with another

lady. She has told the hack driver who is to take her to the tea

party that On the night of the Stumfold tea party that she doesn't

want to arrive before 9:00 p.m. for an 8:30 p.m. party but is in a

twitter on the night in question and thinks that the driver has

forgotten She is embarassed when her own maid points out "He

understands miss . . .don't you be afread;he's a-doing of it every

night.. . .Then she became painfully conscious that even the

maidservant knew more of the social ways of the place than did she."

Of course, when Miss Mackenzie arrives at 9:00 p.m., it turns out

that she has kept the party waiting on her as Mrs Stumfold so nicely

points out. Mr. Stumfold has the sense to let the whole thing pass.

The entertainment of the evening begins with a prayer and a bible

reading by Mr. Stumfold's curate, Mr. Maquire (he of the overly long

second Sunday service sermon). Trollope does a nice character sketch

of Mr. Stumfold here which succiently explains his popularity. He

jokes, he and his disciples flirt mildly and he makes things

interesting enough that the Stumfoldians believe that they are

experiencing society. It's similar to experiencing a climb up Mt.

Everest from the comfort of the easy chair in front on the TV.

Mr. Peters is brought into the story at this point. He is the

provider of the comforts of the Stumfoldians. His money was

apparently made in some shady ways but it is being evangelically

laudered by Mr. Stumfold's use. And as Miss Todd says of Mr. Peters,

if he hasn't repented of his evil, he has forgotten all about it

which is generally the same thing. Mrs. Stumfold makes a show of

bringing her father his tea and toast, which daughterly act excites

the admiration of the Stumfoldians.

Two more of Mr. Stumfold's disciples are now brought to the

forefront. Mr. Startup, an open air preacher, presides

over one of the tea tables and waits on and flirts with all the

ladies. He annoys Miss Mackenzie by flitting around until she wishes

he would sit down. The other disciple, Mr. Fridgidy, is shy and

reserved and seats himself by the biggest chatterbox in the room,

Miss Troller, so that he doesn't actually have to converse with

anyone.

Miss Mackenzie, in the meantime, has taken notice of Mr. Maquire.

From the back, Mr. Macquire is quite a handsome man and just as Miss

Mackenzie is becoming interested, he turns around. That,

unfortunately, is a deal breaker. He has a horrible squint in his

right eye which disfigures his face and disconcerts Miss Mackenzie.

Mr. Stumfold leads his newest guest, Miss Mackenzie, to the tea

table and Mrs. Stumfold then makes her feel completely troublesome

by asking her to fix her own tea to "save the labor." When Margaret

ventures sympathy to Mrs. Stumfold for having to work so hard, Mrs.

Stumfold brusquely replies "I'm quite used to it, thank you." Very

hosptitable, thatTea moves forward and Miss Baker addresses Miss

Mackenzie. Miss Baker is rather hurt that Miss Mackenzie did not

return her call. Margaret, realizing that she has commited yet

another social gaffe, apologizes to Miss Baker and obtains her

address. They have a comfortable conversation for a while, but,

alas, Miss Baker leaves and Miss Mackenzie is left to the mercies of

Mr. Macquire who seems to have figured out that there is a pigeon

for plucking in the room. Miss Mackenzie, to her dismay, cannot keep

from staring at his squint. Mr. Macquire proceeds to wax

enthusiastic about the many virtues of Mr. and Mrs. Stumfold. He

admires Stumfold's cheerful industry. Maquire's motto is "We may not

be happy in this world, but we can be cheerful." I know a lot of

people who have that motto. They're usually extremely depressing to

be around.

(Incidentially, for those who have read this chapter and are more up

on their New Testament than I - exactly Why was Peter in Prison like

a little boy with his shoes off? As a Jewess with a very limited

knowledge of the New Testament, I tend to miss a lot. Miss Mackenzie

asks Mr. Macquire for the answer but he weasels out of it. Probably

doesn't know the answer is my bet.)

Maquire begs Miss Mackenzie to join the Stumfoldians. He begins by

painting a rosy picture of the evangelical life and ends up with the

cheapness of Littlebath.

The party breaks up and the Stumfoldians begin walking toward their

homes. Miss Mackenzie gives Miss Baker a ride

in her fly.

Chapter 5

Everyone can now talk freely about Rubb, Macquire and Ball as

they've all been introduced. The weights have been

removed from the tops of the offending books.

Mr. Rubb returns, about a week after Mrs. Stumfold's party, to make

sure that Margaret's money is going to go to

the mortgage. Her lawyers have advised her that the loan appears

reasonably sound. Margaret appears to have a

sneaking liking for the handsome Mr. Rubb but she is very concerned

that socializing with him will somehow hurt her

social standing.

We in the US tend to laugh at this concept until we

start to think. How many college professors do

you see married to janitors, even if the janitor is a worthy person?

How many judges are married to factory

workers? We in America are almost more snobbish because our social

classes are more fluid. Make enough money or get

enough education and you can change your social standing. And once

you get there, you try to make sure that

everyone else knows you're there. And you don't marry the janitor.

And as Trollope points out, what is Miss

Mackenzie doing that we don't do. Left alone is the world, she is

trying to pick the best people for her frends from those who are

offered to her. The sad thing about this is Margaret is really

attracted to Samuel Rubb and, probably, of all the marriages she

could make, that would have probably been the most sexually

satisfying one.

So, Mr. Rubb and Miss Mackenzie are talking over the loan, he

assuring her that she is doing a wonderful thing with

her money. Suddenly, to Miss Mackenzie's dismay(and sneaking

interest) Rubb stops talking business and starts talking about the

Stumfoldians. He passes on some gossip - Mr. Stumfold is going in

for a bishopric but Rubb doesn't think Stumfold will make it.

Stumfold is too strict for the current taste. Rubb also reveals that

Peters controls all the money and is constantly arguing with his

daughter. Rubb warns Miss Mackenzie that Maquire is on the lookout

for a wealthy wife, preferably without a father. Then Mr. Rubb drops

a little compliment about Miss Mackenzie's personal attractions.

Very smart of him. I don't think any of the other suitors have

thought of that yet. The idea of Maquire looking out for a well -off

wife is interesting to Margaret. Could she set up as another Mrs.

Stumfold?

Mr. Rubb is everything that is pleasant and friendly. Based on the

longstanding relationship between Rubb and Mackenzie, it seems only

natural to Mr. Rubb that he and Miss Mackenzie should be friends.

(Lord, they were using that line even then. Probably came right

before the one about how he loved animals.) Miss Mackenzie believes

she is somewhat obliged to be Mr. Rubb's female confidante, as he

has no0 other near female relative, but she's rather

annoyed at the idea. Margaret tries to get out of it by pointing out

the distance between their homes but Rubb

points out that its just a short train ride. Mr. Rubb then coyly

brings up Miss Mackenzie's previous advice to him

to marry. He might have asked her to marry him but he judges that

the time is not right. Instead, he finagles a

return invitation for the evening to check in on Susanna, the

teenage niece. Susanna, on her return, reveals that

she knows and cares absolutely nothing about young Rubb. Rubb

however wins Susanna over, temporarilly, with the

present of a workbox. After Mr. Rubb leaves, Susanna informs her

aunt that young Rubb is a much more refined

article than old Mr. Rubb. Susanna thinks Mr. Rubb is "downright

handsome". She tells her aunt that she has been

told at school not to talk about men being handsome. I think this is

a jab from Trollope. He has no patience for

all these woman scorning marriage and interest in men.

Mr. Rubb leaves and Miss Mackenzie, outside of business, hears

nothing from him. She does, however, get a rather

unsettling business letter. Rubb and Mackenzie wanted the money

before the mortgage papers had been signed. Would

Margaret give them the money. Her lawyer tells her that since it is

a family matter, she might be willing to do it

although, normally, he would not advise her to give her money

without security. Margaret agrees to advance the

money in October. However, the mortgage papers have not been

finished by Christmas. Mr. Rubb continues to assure

Miss Mackenzie that everything is all right and Miss Mackenzie

continues to believe Mr. Rubb.

In the meantime, Miss Mackenzie has joined the Stumfoldian group and

become great friends with Miss Baker. She is

going along pretty happily until she is taken to task, one day, by

Mrs. Stumfold for some small failing and the

entire Stumfoldian party falls in line behind Mrs. Stumfold.

Margaret is still a Stumfoldian but a soiled one. In the meantime,

she has given up trying to make friends with Miss Todd and only nods

to her in the street. The

Stumfoldians won't allow of such a friendship. THe only person

allowed to be friends with Miss Todd is Miss Baker

because they've known each other so long.

But things are a changing by the end of Chapter 5 - Margaret is

invited to spend her Christmas holidays away from

Bath and, so, in the next chapter, we have a change of scene and

peoples.

Rose Rowland

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie - Chapter 3: Miss M Reinventing Herself

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

She turns out to be one of the maiden English ladies we Americans

are so awed by.

Miss Todd may not be quite so maidenly. She is accompanied by two children

and is decsribed by the narrator as their aunt. Yet Trollope puts the suggestion

in Misss Todd's mouth that she is the mother of the two girls. "When the Popes have nephews,

people say all manner of ill-natured things. I hope they aint so uncivil to us."

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie - Chapter 3: Miss Todd as Frances Power Cobbe

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

"When Miss Todd appears,

she turns out to be one of the maiden English ladies we Americans

are so awed by. I picture her, Miss Todd I mean, striding across

LittleBath in sensible shoes and a ugly hat, running everyone's

business and being the life of any party - a "good sort."

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie: The Dullness of John Ball; an Austenish Book

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

As for John Ball, I think Trollope went out of his way to create the

dullest character ever when he created the fellow.

Subject: [trollope-l] What does Stumfold do for a living?

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie, Chapter 4 and 5: The Complications of

Class

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Home

Contact Ellen Moody.

Pagemaster: Jim

Moody.

Page Last Updated 26 December 2004