Date: Sun, 6 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Chaper 6: Miss Mackenzie goes to the Cedars

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

There is so much in this chapter to discuss, and I hope everyone chimes in. On the one hand Miss Mackenzie is trying to find a her way in the world and discover a social circle for herself. On the other, suitors and family members are honing in on her money. Trollope is subtle, and acerbic in showing that in spite of the money grubbing, people like the Mackenzies and the Balls live under the illusion that they are entitled to the money, and that they are doing Margaret a favor in condescending to know her, as Jane Austen might say.

Miss Mackenzie (Margaret) has received an invitation to spend the Christmas holidays at the Cedars, home of the Ball family. She writes to Susanna's mother, and asks Mrs. Mackenzie that Susanna be allowed to spend the holidays with her own family in their at Gower Street. The ever fault-finding Mrs. Mackenzie becomes idignant. She's sure that the Balls are after Miss Mackenzie's money. She further complains that Miss Margaret Mackenzie is now in charge of her daughter, and that her daughter should stay with Miss Mackenzie. It seems logical that a young girl would enjoy Christmas with her family.

But we aren't talking about logic here, nor the feelings of young Susanna. We're talking about money. Mr. Rubb has extracted a dubious loan from Miss Mackenzie, for the benefit of the firm of Rubb and Mackenzie. Mrs. Mackenzie has suddenly found all sorts of new charms in the person on Mr. Rubb. She has a change of heart and writes to Miss Mackenzie, urging her to stay a a few days at Gower Street on her way through London. Mrs. Mackenzie is no skilled letter writer: ("but still there was that quality in the letter which plainly told an apt reader that there was no reality in the professions of affection made in it. ... Available hypocrisy is a quality is a quality very difficult of attainment and of all hypocrisies, epistolatory hipocrcrisy is perhaps the most difficult.") Margaret is smart enough to see right through her sister in laws motives, but she accepts the invitations none the less.

Although Margaret has no liking for the Cedars, she spends Christmas there. At the Cedars, we see a fine example of the penny pinching impoverished aristocracy. Appearances are all that count. The house is dreary, as are the grounds, a portion of which is let out for grazing. A carriage must be kept to keep up appearances, but the horses are let out for hire in the field when they are not needed to pull that status symbol - that Victorian SUV, the carriage. Not only is the house dreary, but so, alas, are the occupants. Old Lady Ball "made efforts to be aristocratic in her poverty." Old Sir John is an embittered old man. His son, John Ball, must labor away in the sphere of business. He is not very effective in growing his limited capital. Mr. Ball is a widower with nine children. It certainly seems as if Margaret is in for a gay time with these people.

Sir John urges his son to ask for Margaret's hand at once, even though Margaret is "not a beauty ... (who) won't set the Thames on fire." In his plodding way, John Ball makes himself pleasant to Margaret, but is troubled by the loan Margaret has made to Rubb. Rather than billing and cooing with Margaret, he fusses and frets over the terms of the loan. Some men can't leave the their work at the office.

During a tedious carriage ride (what will people say if the Balls do not keep a carriage!) Lady Ball goes to work on Margaret, trying to pry her loose from those low, oilcloth vending, Mackenzies. Lady Ball urges Margaret to stay at the Cedars a bit longer. ( So that John has more time to work on his ineffective courstship.) Lady Ball is angry when Margaret declines. Lady Ball becomes all high and mighty when Margaret has the effrontery to decline the invitation.

Here we have a delicious Trollopian aside:

"'What a wicked old woman she was!' virtuous readers will say; 'what a wicked old woman to endeavor to catch that poor maid's fortune for her son!' But I deny that she was in any degree a wicked woman on that score. Why should not the two cousins marry and do very well together with their joint means? Lady Ball intended to make a baronet's wife of her. If much were to be taken, was not much also to be given?"

John Ball way lays Margaret on the last night before she intends to leave. He asks her for an interview the following morning.

Hmm. Wonder what he wants?

Catherine Crean

Date: Sun, 6 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Chapter 7: Miss Mackenzie Leaves the Cedars

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

(Sorry - I was off on the timing of John Ball's invitation. He asks to talk to his cousin Margaret after evening tea, on that same day. Mea culpa.)

Although Margaret is aware that she might receive an offer from John Ball, she worries that her cousin may wish to discuss money matters with her. After an unpleasant remainder of the day, consisting of ill-natured bullying by Lady Ball and Sir John, Margaret has her interview with her cousin, John Ball. There follows one of the most pitiful proposals of marriage I have ever read. In his own sly way, Trollope must have had fun with this bit. He wrote many, many such scenes. This proposal scenario is not fraught with drama, nor romance, nor yet broad comedy. It is an example of a rather dull man who means well, setting out a logical business arraignment of sorts. Is he hiring a housekeeper? Trollope is even-handed here. He himself states that John Ball did pretty well in his proposal. Margaret is too overwhelmed to give John an answer at that moment, but promises to write to him with her decision. There is a poignant scene where John and Margaret look into each other's eyes, after John promises to love Margaret most tenderly.

"So saying he (John Ball) put out his hand and she took it; and they stood there looking into each other's eyes, as young lovers might have done; - as his son might have looked into those of her daughter, had she been maried young and had children of her own, In the teeth of all those tedious money dealings in the City there was some spice of romance left within his bosom yet!"

I think Trollope is thinking of himself here. But even if he is not, Trollope is being even- handed in his portrayal of the rather stick-like John Ball.

Unfortunately, Margaret must face the formidable Lady Ball before she goes to bed. With her typical well bred grace, Lady Ball approaches her future daughter-in-law with sweet words. "Well, Margaret? Well?" and then further bullies and insults Margaret for not taking John's offer on the spot.

"It is astonishing the harm that harm that an old woman may do when she goes work, and when she believes she can prevail by means of her own peculiar eloquence. Lady Ball had so trusted to her prestige, to her own ladyship, to her carriage and horses, and to the rest of it, and had also misjudged Margaret's ordinary mild manner, that she had thought to force he neice into an immediate acquiescence by her mere words. The result, however, was exactly the contrary to this. Had Miss Mackenzie been left to herself after the interview with Mr. Ball: had she gone upstairs to sleep upon his proposal, without any disturbance to those visions of sacrificial duty which his plain statement had produced: had she been allowed to leave the house and think it over without any other argument to her than those he had used, I think that she would have accepted him. But now she was up n arms against the whole thing. .... She was claimed as a wife into the family because they had thought that they had a right to her fortune; and the temptations offered, by which they hoped to draw her into her duty were a beggarly title and an old coach! No!"

The next day, Margaret has an unpleasant leave taking, as John implores her to think well of him. And so Miss Mackenzie leaves the Cedars, and all its pleasures.

In Chapters 6 and 7 we see that Margaret has character and backbone. For a woman who has led such a sheltered life, she has a strong sense of right and wrong; of sincerity and falseness.

Catherine Crean

Date: Sun, 6 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Chapter 8: Mrs. Tom Mackenzie's Dinner Party

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I must make a disclosure, and the journalists say, before I summarize this chapter. It is one of my favorite chapters in the book. It is a long chapter, too, with many subjects of conversation. So I must roll up my sleeves and jump in! If I get details wrong, or am incorrect in my interpretation of Victorian manners, particularly as regards dining, I'm certain that the members of this group will set me right.

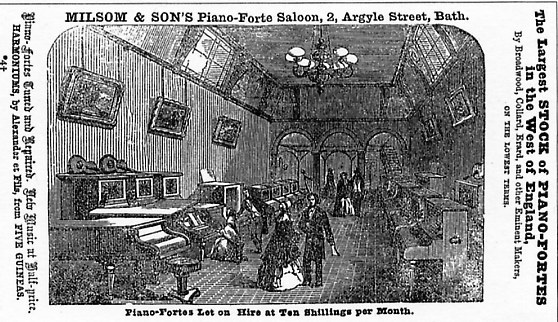

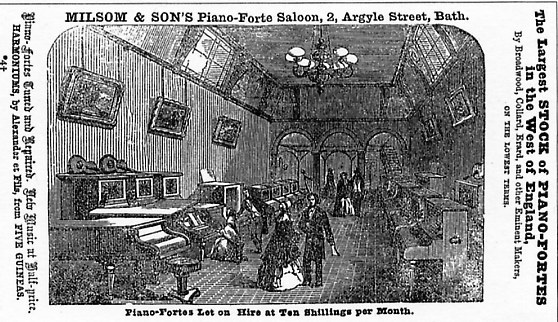

Margaret Mackenzie's next stop is Gower Street - the home of Mr. and Mrs. Tom Mackenzie. Not one to waste any time, Mrs. Mackenzie announces that there is to be a dinner party that very day. The guests include Dr. and Mrs. Slumpy, a Miss Colza (bedecked in curls and pink ribbons), and Mr. Rubb. Mrs. Mackenzie is quite particular in remind Margaret of Mr. Rubb, and to mention several times that Mr. Rubb is to take Margaret down to dinner. There are many descriptions in Vicotorian literature of dinner parties gone wrong. Dickens has a go at it with the Podsnaps. Thackeray's short story A Little Dinner at Timmin's is a masterpiece of ever escalating horror. Trollope takes his turn in this chapter. As we know, Trollope liked his food. There is a passage somewhere in Trollope (somebody help me!) where he lays down the law as to how dinner should be served. The hot food should be hot, the cold food should be cold, and there should be plenty of it. Furthermore, all the dishes for the course should be on the table at the same time. Service "a la Russe" was coming into vogue in the late Vicorian era. From what I gather, this meant a great deal of ceremony with foods being served to each guest individually by footmen. (Surely somebody else can describe this more accurately.) Further, it seems that some hostesses, wanting to impress, relied upon outside help in the form of specially hired servants and "made dishes" from shops. Not every household is the equal to that of the Pallisers.

Needless to say, the dinner is a fiasco. A "Mr Grandairs" (who seems to be a butler-for-hire) directs the flow of meal, disregarding Mrs. Tom's instructions. Once the party is assembled in the drawing room, there is an uncomfortable wait as dinner is delayed. Finally, the party is seated, only to experience more delays and stilted conversation. A rebellion is afoot in the kitchen, with cook irate, and the maid servant in tears, as Mr. Grandairs takes charge. Mr. Grandairs "had seen the world" and knew which rules "prevailed in the world of fashion." As Trollope says "Ruat dinner, fiat genteel depertment." This is a clever self-referential joke to one of Trollope's favorite Latin catch phrases.

In consequence of the Grandairs approach, the soup is cold, the gravy congealed, and most of the meal barely edible. Even the chatty Miss Colza's conversation starts to flag. Mrs. Tom is devasted. Even her effort to induce Elizabeth to carry the gravy boat around is quashed at once by Grandairs Ah! but worse is to come!

Let us not be distracted by the Grandairs' reign of terror. We must get on with the love story. Mrs. Tom has set up this scenario so that Mr. Rubb may further his pursuit of Margaret Mackenzie and her money. Before dinner, he had done his best to make conversation with Miss Mackenzie, to no great effect. Now downstairs "amidst the tyranny of Grandairs" Mr. Rubb makes another attempt. Miss Mackenzie confesses she has never been to a dinner party in her entire life.

The real crisis comes when it is time to serve the champagne - one bottle. Mrs. Tom had told Grandairs whom to serve champagne and whom not to serve, as there is not enough champagne for the entire party. Mr. Grandairs will have none of this, and he pours round the champagne in the "correct order" to all until the champagne bottle is empty, leaving some guests with no champagne at all. Mr. Grandairs seems to take sadistic glee: "When the bottle came round behind Miss Mackenzie back to Dr. Stumpy, it was dry, and the wicked wretch (Grandairs) held the useless nozzle triumphantly over the doctor's glass."

As the dinner goes on, Mr. Rubb is chatting with Margaret Mackenzie. Miss Colza engages in conversation with Mrs. Tom. She tries to shoot down Miss Mackenzie by remarking upon her progress with Mr. Rubb, and then comparing Margaret to "an interesting looking" woman they all know. Trollope, a veteran of many dinner parties, must have seen many Miss Colzas as he knows her sort well. Miss Colza continues launching attacks on Mr. Rubb, reminding him of previous flirtations.

The dinner drags on, with the mutton served cold, and the sauces not circulated. Finally the meal ends with "colored pyramids of shaking sweet things which nody would eat, and by the nonconsumption of which nothing was gained, as they all went back to the pastrycook's" and "ice puddings flavored with onions." Delightful, no?

Trollope inveighs against Mrs. Tom's pretense. He is all for the old ways, and no pretense about it. Honest British mutton and potatoes, served up hot at table, with the father of the house doing the carving.

As the evening draws to a close, Mr. Rubb makes some clumsy attempts to discuss the money Margaret Mackenzie has loaned the firm. Margaret Mackenzie puts her faith in Mr. slow to put things right. Miss Colza cannot reisist another attack - she comes upon the couple and finds them "very conffidential." Mr. Rubb gives Margaret a Trollopian hand press as they part for the evening. The next morning, Margeret Mackenzie and Susanna leave Gower Street and arrive safely at Littlebath.

Catherine Crean

Date: Sun, 6 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie: Chapter 9: Miss Mackenzie's Philosophy

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I'm sure I will not do this chapter justice, and I look to you all to help find the meaning of "Miss Mackenzie's Philosophy."

Margaret Mackenzie is back in Littlebath with much to ponder. She thinks of Lady Ball's poo- pooing of romance, or "billing and cooing" as she choses to call it. Margaret thinks kindly of her cousin, but sees him as a stooped balding man, worn down by the cares or the world and the responsibility of a large family. He is used up. "The juices of life had been pressed out of him." Was Margaret not due some romance? She looks at herself in the mirror. She sees her silken hair, her bright eyes, her blooming compexion, and wrapping her scarf round her bosom, her womanly figure. She smiles and sees a dimple on her chin. Impulsively, she kisses her image in the mirror. This is a very sensuous passage - rather startling for Trollope.

Margaret writes to John, declining his offer of marriage. John dutifully shows her letter to Lady Ball who reacts exactly as we might expect. Lady Ball continues to insult Margaret, yet she urges John to go to Littlebath. John declines, saying he will take no further steps. Lady Ball writes to Margaret askign her to come back the Cedars, pressing arguments that "did not prevail with Miss MacKenzie."

Miss Mackenzie continues her quiet life in Littlebath for the next few months. She continues associating with the Stumfordians, but Mrs. Baker is the only person to whom she feels close. She continues to be rather snubbed by Mrs. Stumford and the coachmaker's wife. In time she comes to become disenchanted with her relatisonship with the Stumfordians. She thinks they are not ladies. Here follows a meditation on what it means to be a lady. I suppose this part of the chapter is "Miss Mackenzie's Philosophy." I don't quite get the lady/gentleman thing. She thinks about Mr Rubb and the "sphere" of life to which he and her brother belonged. I totally don't understand her thoughts here. She comes to a the conclusion that she would rather break her heart than marry a man who is not a gentleman. She also expresses horror at eating with a steel fork. (I suppose ladies use silver forks, or starve to death.) She does bbelieve that ladyhood comes from within, not from the company in which she finds herself. She may be innately a lady, while drinking tea with the vulgar Stumfoldians.

Mrs. Todd - who represents the opposite to the Stumoldians continuing her parties and her card playing. Miss Baker and Miss Mackenzie stick with Stumfoldians, wanting to be religious in some way. Miss Mackenzie decides to give a tea party, and she and Miss Baker discuss the guest list. If all goes as plans, this wil be an interesting party. Mis Todd, Mr. Rubb, Mr Maguire, and assorted Stumfoldians in the same room? No Miss Colza, though.

P.S. Trollopian clue - Miss Mackenzie has a dimple!

Catherine Crean

Date: Sun, 6 Jun 2004

Subject: RE: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie, Chapters 4 to 9: The Stumfolds' tea party

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I had been a little concerned that the discussion on Miss Mackenzie had gone rather quiet this week. Sophy's email this morning explained a lot. I am sure that the list are all concerned to hear of her accident, and will join with me in wishing her a speedy and complete recovery.

The Stumfolds' tea party is a wonderful piece of Trollopian description. You can easily imagine yourself being there and shuddering. Mrs Stumfold's pretensions, her attention to her rather dubious father who appears to be the source of all the good things in the Stumfolds' life and the way in which she gets the guests to help themselves to food and drink on the grounds that it cuts down the work, and not because they are urged to make themselves at home, gives us a perfect picture of the sort of person she is. On the whole her husband seems harmless enough. While he is clearly making the most of the good things that he has got with his wife, he probably received the pew rents and donations from his ministry, even if as an evangelical clergyman he probably received no stipend as such.

Mr Maguire is another kettle of fish. Trollope makes a great deal out of his squint, but I find it difficult to believe that it was as bad as he suggests. We have probably all known someone with a squint, and although a great deal is done nowadays with both spectacles and surgery, I find it hard to imagine someone whose squint made him so dreadful to look at in the manner that Trollope suggests. I think that what he is trying to do is to show that Maguire's inner nature was reflected in his facial disfigurement. Certainly nothing appears throughout the novel which makes him appear to be either deserving or admirable.

I am as puzzled as Miss Mackenzie about Mr Stumfold's riddle about St Peter. I don't think that we are ever told the answer. Since Margaret Mackenzie was unable to find the answer by an hour's consultation of her Bible, I don't suppose that I shall do any better. Have any Bible experts got any ideas?

Coming on the Chapter 5, I have always found Samuel Rubb unattractive. He sounds like a con man, and one wants to shout 'don't do it' when Margaret is persuaded to lend her money before making sure that the mortgage is properly set up. Other list members seem to think that he has some attractive features, even if he is evidently not a gentleman. Apart from talking to Margaret as if she is a human being, I don't see anything else appealing about him.

Having been concerned that we were not getting anything to comment on, we have now been given a host of reading from Catherine. I shall read her contributions again, before I join in with any comments.

Regards, Howard

Date: Sun, 6 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Stumfold's joke

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Many thanks for your kind words, Howard. I have chapter 10 yet to do, so my work is not over yet.

As far as Stumfold's joke goes ("Why was Peter in prison like a little boy with his shoes off?") the only answer I can think of his a pun on soul/sole. Something to do with "bared soles/souls" or "naked soles/souls." If you posted this riddle on Victoria-L you'd probably get the answer. I'm betting it was an old chestnut, so to say.

Regards,

Catherine

Date: Sun, 6 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie, Chapter 10: Plenary Absolution

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Margaret Mackenzie receives an unpleasant letter from Mr. Slow regarding the loan she made to Messrs. Rubb and Mackenzie, in order to buy premises. To cut through all the legalese, there is no security for the money, as the property in question has been mortgaged already. Slow states that Mr. Rubb has "laid himslef open to proceedings" (i.e. behaved in a deceitful way.) Further, the letter gives the impression that firm of Rubb and Mackenzie is on shakey financial ground. Miss Mackenzie succeeds in "whitewashing" Mr. Rubb in her own mind. She considers the money a gift to her brother. Miss Mackenzie writes a letter to Mr. Slow that is "a false letter" although she is not sensible of the falseness. She let's Mr. Rubb off the hook.

Miss Mackenzie is startled by the appearance of Mr. Rubb, who comes to visit her. Mr Rubb then "works Miss Mackenzie over" so to say. He sounds like a con artitist to me, blaming lawyers for making things difficult. Miss Mackenzie is ready to forgive the loan, but she is wise enough not to show Mr. Rubb the letter that Mr. Slow had written her, although Rubb requests to see it. She does, however, show Mr. Rubb a copy of the letter she wrote to Mr. Slow in response.

Now here comes, in my mind, a troublesome passage. After Mr. Rubb wipes a tear from his eye :

"That tear which he rubbed from his eye with his hand counted very much in his favour with Miss Mackenzie; she had not only forgiven him now, but she almost loved him for having given her something to forgive. With many women I doubt whether there be any more effectual way of touching their hearts than ill-using them and confessing it. If you wish to get the sweetest fragrance from the herb at your feet, tread on it and bruise it."

Perhaps this an astute insight into the workings of women's hearts, an albeit arguable one. But the imagery of not only crushing an herb to get the finest fragrance, but crushing the herb under foot is troubling. First of all, the herb is on the ground - beneath the man, second of all, Trollope talks about "treading" on the herb to the point of "bruising" it. There is sometimes a sadistic side of Trollope when it comes to women.

As Mr. Rubb is in the midst of collecting himself (and examing the soles of his boots, no doubt to smell that wonderful aroma that the treading and crushing has produced) when who should walk in but Miss Baker. Miss Mackenzie sees in an instant that Miss Baker does not think well of Mr. Rubb. There ensues some chit chat about the weather, that reliable conversational standby. But then Miss Baker announces the purpose of her visit. She is inviting Miss Mackenzie to drink tea with Miss Todd. Miss Baker assures Miss Mackenzie that the company will not consist of Miss Todd's "regular set" and that Mr. Maguire will not be there. Margaret accepts the invitation. Mr. Rubb remains for half an hour buttering up Miss Mackenzie and trying to get information out of her regarding Mr. Maguire and the Stumfoldians.

Miss Baker calls on Miss Todd and tells her that Miss Mackenzie will accept her invitation, and mentions that Mr. Rubb was with Miss Mackenzie when she called. To Miss Baker's horror, Miss Todd says that she will invite Mr. Rubb too. Mr Rubb is still ensconced on the sofa when the note of invitation for him arrives to Miss Mackenzie's hands. Miss Mackenzie is hoping that Mr. Rubb will decline the invitation, but he accepts. Worse, he says he will escort Miss Mackenzie to the tea. Mr. Rubb finally makes his departure (what a barnacle) but not before calling Miss Mackenzie "the best friend (he) has in the world" and giving her another hand press.

Finally left alone, Miss Mackenzie ponders what the events of the morning mean. Is she "allowing herself to fall in love with Mr. Rubb, and if so, was it well that it be so?" As she thinks of this, she thinks also of John Ball and Mr. Maguire.

She has given "plenary (full) absolution" to Mr. Rubb, but perversely he has insinuated himself into a situation where she feels she now owes Mr. Rubb something.

Catherine Crean

Date: Sun, 06 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie: In Defense of Mr Rubb

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Many thanks to Howard for his kind words. The whole thing would have been amusing if it hadn't been so painful. I was leaving with my eldest son from his doctor and managed to catch my heel in the third stone step on the way out. I was so throrough that I sprained one ankle, twisted the other knee and skinned most of the skin off my legs. I then had to submit to the indignity of being treated in a pediatrician's office (I'm 42) and, in true Victorian fashion, took to my bed for a couple of days although with the delightful addition of 20th century painkillers.

I've followed Catherine's postings on chapter 6-10 with great admiration for her industry and quickness. I'm chiming in in defense of Mr. Rubb - no surprise there. I don't see him as a con man as much as a desperate man trying to save his business. I really don't think that he starts out with any intention of defrauding Margaret. I think he really intends to give her the mortgage. And even when he is not able to secure the property, I'm sure he is always thinking that he can somehow put the thing right with enough time. My sympathies are with Samuel Rubb, Jr. As I hide money from Peter to pay Paul each month, I could see how he could talk himself into thinking that he's not doing much of anything wrong.

As to John Ball, in a sense he is hiring a housekeeper. He's looking for someone to run his home as much as be his companion. We often forget how much the character of marriage changed in the last century. As Trollope said earlier, a wife was not only a wife but a partner in the business and the business was managing the family and the home, a not small undertaking in those days. I think Trollope, while he is laughing at them, is trying very hard to be evendhanded in his view of all the suitors.

I need to make one small observation on Catherine's view of Miss Mackenzie's philosophy. It is Miss Baker who would rather break her heart than marry a man who is not a gentleman. As for Miss Mackenzie's philiosophy on ladyhood, I think it has a great deal to do with self esteem. We each create an image of ourselves (i.e literary types who read Trollope for pleasure) that places us on a certain sphere from which we look out on the world with safety. Miss Mackenzie would probably no sooner wish to stop being a lady than I would wish to burn down my local library or cease reading books. It is an integral part of my image of myself. The main problem I have with Miss Mackenzie's philosphy, vis a vis Mr. Rubb, is that she never thinks that she can stay a lady, marry Mr. Rubb and then bring him up to her station. Mr. Rubb is obviously teachable. He has learned to be more of a gentleman than his father and who better than a wife to set him on the proper way?

As for the herbs underfoot, I think Trollope really has something here. We all know women who love men better the worse the men treat them. I think Trollope is actually disgusted with Miss Mackenzie's behavior here and wishes she would stand up for herself better.

Cheers, Sophy

Date: Sun, 6 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Mr. Slow

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Mr. Slow, who appears in Miss Mackenzie as a lawyer, is, of course, an old friend. He belongs to the firm of Slow and Bideawhile, whom we have met in The Way We Live Now, Framley Parsonage, Orley Farm, and He Knew He was Right. The firm of S & B follows their names by never hurrying to any conclusion of any kind.

Sig

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie: Class and Money

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Rose Rowland wrote:

How many college professors do you see married to janitors, even if the janitor is a worthy person?

Sophy, I'm laughing at this analogy because I took a year off from college and worked as a night janitor at a college. What a terrific job it was! I finished my work in a couple of hours and spent the rest of the evening locked in a professor's vacant office reading War and Peace, The Golden Bowl, and other classics. And, true, I had no marriage proposals from professors (though the other janitors checked me out).

But Mr. Rubb has his own business and is Miss Mackenzie's brother's partner, so I think he is of a higher standing than janitors, surely. In 19th-century novels, it's always clear that trade is looked down upon, but Miss Mackenzie enjoys his company because he is intelligent, smooth-talking, and charming, though she won't admit this to herself. But his manners are apparently not as good as hers, because she is offended that he considers himself her equal and chats casually with her after he finishes talking about business. Trollope writes: "Miss Mackenzie had been brought up with contempt and almost hatred for the Rubb family." He admits she has a prejudice, and in some ways that makes her to me a less interesting heroine than some others I have encountered.

This novel is SO much about class and money. Miss Mackenzie is constantly worrying about her social position and how to improve it, and this all comes about through her inheritance of her brother's money. Money makes the (wo)man here and certainly provides an abundance of social opportunities and romantic overtures that wouldn't have existed for her previously.

Kathy

Date: Mon, 7 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Mr Rubb as Con Man

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Let's look at the evidence for Mr Rubb being a con man.

The question of a loan is first raised by Margaret Mackenzie's brother, Tom, in Chapter III. His letter stated that the money was to be spent on the purchase of the premises in the New Road, and she was to have a mortgage on them. He promised that Samuel Rubb, junior, would run down to Littlebath in the course of the next week, so that the whole thing might be made clear to her. When Mr Rubb came, he explained that, while they could procure the money on mortgage from an assurance company, they would prefer that the control of the premises should be in the hands of someone connected with them. The great 'opportunity' for investing her money might now slip through her hands because of her lawyer's slowness in investing her money. This is a classic trick to unsettle a dupe before laying hands on his or her money. After thinking things over, she wrote to Mr Slow, telling him that she was very anxious to oblige her brother if the security was good.

Problems begin to arise in Chapter V, when we learn that Rubb and Mackenzie wanted the money at once, whereas the papers for the mortgage were not ready. Mr Slow gives Margaret the option of advancing the money before the mortgage is ready, although he would not normally recommend such a practice. I am reminded of a story told to me by a friend, who had asked a lawyer for advice about an investment. The lawyer had replied in lawyer-speak 'On the one hand ... on the other hand ...'. My friend said 'If you were my father, and I came to you with this proposition, what would you say?'. The lawyer replied 'I should forbid you to do it!'. It is a pity that Mr Slow did not write to Miss Mackenzie in similar terms.

At the dreadful dinner at the Tom Mackenzies, Mr Rubb tells Margaret that the property is purchased, but that 'the title deeds are at present in other hands, a mere matter of form'. This was the point at which the alarm bells in my head began to ring without stop. Mr Rubb says 'The security is not as good as it should be. I will tell you that honestly; and if we were dealing with strangers we should expect to be called on to refund. And we should refund instantly, but at a great sacrifice, a ruinous sacrifice'. What he means is that Rubb and Mackenzie have borrowed the money twice - once legitimately on mortgage and once from Margaret without security. For my money that's the behaviour of a con man.

As Sig says, we have encountered Slow and Bideawhile on several occasions, and in none of them did they exactly shine. We shall see later on in the novel how it has taken them fifteen years to discover a miscarriage of justice which has a fundamental effect on the final stages of Margaret Macdonald's story. In the hands of a con man like Samuel Rubb they are clearly putty.

Regards, Howard

Rose Rowland in reply:

I don't see him as a con man as much as a desperate man trying to save his business. I really don't think that he starts out with any intention of defrauding Margaret.

Rose

Date: Mon, 7 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Mr Rubb. con man?

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

As I see it, having just returned to catch up with the Miss M postings, I think it is a bit hard to dub Rubb a con man, insofar as such a creature goes out of his way to gull strangers. Mr Rubb on the other hand is not only desperate but would like to borrow from someone who might have sympathy with the firm's plight. I am sure he would like the security to be good but when it turns out not to be he persists. This is unscrupulous and to be deplored - and he knows it - but, alas, in the ultimate his needs must prevail even at the risk of another's financial discomfiture.

I go along with those who greatly praise this short novel. I think the first three chapters are an exemplary exposition, the dinner-part a delight. Can someone else please remind me where in Troillope there is another very amusing dinner party, where the parsimonious wife's scanty fare for the husband's guest is disastrously embarrassing?

Finally, the trip to Littlebath, aunt and niece, put me in mind of the stay in Bath of Fanny Trollope's Widow Barnaby. The characters (except the nieces) have nothing in common but it is interesting to reflect on Anthony's inevitable familiarity with his mother's work.

Regards to all,

David

Re: Fanny Trollope's Widow Barnaby and Michael Armstrong: Character Types and Disastrous Dinner Party

I do agree about the Widow Barnaby. Fanny's influence might also be seen in a disastrous dinner party in the first chapter of Michael Armstrong. It takes place on a very hot evening.

'The very sight of the servants as they panted round the table was quite enought to smother and stifle all inclination for enjoyment - their shoes creaked - their faces shone - ice became water - the salad looked as if it were stewed - the cucumbers seemd to have fainted away - the prodigious turbot smelt fishy, and its attendant lobster sauce glowed, not with a deeper tint, than did my Lady Dowling's cheeks as her nose caught the unfragrant gale. In short, it was a great dinner in the dog-days, and no more need be said of it.'

Teresa

Date: Tue, 08 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Mr Rubb as self-deluded

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I'd say that Howard's analysis goes very far, but he has left out something: the inner psychology and motives of the man, always very important in Trollope. The outward actions in a court of law would dam Mr Rubb, but a good attorney does not stay with the outward actions. Sophy's point that Rubb is desperate is a good one; Trollope goes beyond this: he suggests that Rubb, like many of us, and like many of the characters in this novel, has a good opinion of himself, needs to have that, acts on a need to believe all will be well.

There is always this question whether a man is a knave or a fool. I incline to see Mr Rubb as a little bit of a fool. As all all the people at that ordeal of a dinner party, all of them prisoners of their absurd desire for prestige to the point they can't even eat their food when it's hot. No one will break out, no one says the emperor is naked, has no clothes on. Grim comedy. Trollope hits out at pretentiousness in the a la Russe set up elsewhere. It's more than that he likes to eat his food when it tastes good: it's the very values underlying this: there's a wonderful explication of his attitudes towards these kinds of strained festivals-showing offs in his New Zealander (a chapter on social life -- very Carlylean).

I haven't got time to quote the passages, but I'd say this view also explains another reason why Trollope shapes the narrative so that the reader will not want Miss M to marry Mr Rubb. Mr Rubb might just lose all her money. He's likely to invest in schemes, to be conned himself. It's a delicate question because he knows the facts and has himself put them aside because he wants to believe otherwise. And Miss M's brother goes along because he wants to also -- but he is nowhere as self-deluded. How he came to marry the harridan-woman Trollope has put in front of us we are left to imagine.

This is a novel which argues for safety. John Ball is the supposedly safe man. His timidity and lack of imagination is precisely what makes his endless work get nowhere though. That's on the side of Mr Rubb. Sometimes luck is with the deluded.

There is real sympathy for John Ball as he allows himself to be crushed by his harridan-female -- in this case a mother. We are supposed to sympathize with this, admire him: a male Griselda is put before us. He does justice to his bonds and thus the world is safer as we can count on him.

The only problem here -- only is an understatement -- is that safety is really not to be won this way. It's a fairy tale that leaves Miss M competent, with a title and "safe" -- albeit she shall have to live with Ball's harridan for the rest of her life. Be silent in front of her. Safety does not come with loyalty nor obedience to mores. The world is a lot more vicious and corrupt than this little tale makes out.

I have to disagree with Mullan on Cheltenham -- or at least qualify his assertions and suggest there is an alternative possibility.

A small point: Cheltenham was a place not far from Bath which had more clout than Bath, and was actually more expensive in the first half of the 19th century. In Austen's later illnesses she longed to go to Cheltenham and they did, once. Being Austen she saw what a delusion that was.

There were little communities right outside the outskirts of Bath which harboured types such as we see in this novel and The Bertrams. They had names with Bath as a suffix or prefix. One such development was Batheaston. This was east of the bridge. Two bit kinds of gambling that we see in The Bertrams -- which could add up if you kept at it (especially if Philip Thicknesse, a real con-man was there), ludicrious pretentiousness of the type run by a Lady Miller (poetess, saloniere-manque), absurd outlets for the "charity" of Countess of Huntington types (super religious evangelical and very bossy, a Lady Catherine de Bourgh in manner). This may also be what Trollope has in mind.

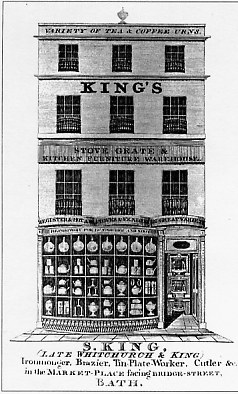

There are some good books on early to later 19th century Bath and its environs. If you can find it the slender Bath: A New History by Graham Davis and Penny Bonsall really gives you a history and picture of the place since the early modern period with a focus on the important 19th century. Another is R. S. Neale's Bath: A Social History, 1680-1850; both will lead you to other books. Many people still see a fairytale myth version of Bath with Nashe, Wood and a couple of other colorful people as heading some delightful place across the century: in fact the heyday of Bath covered a small area in the center; the real builder of Bath was the Duke of Chandos with a conglomerate, which probably included people very like Mr Rubb and Mrs Stumfold's father, Mr Peters. A highly enjoyable and true picture book about Bath is Bryan Little's Building of Bath -- it's loaded with photographs from around 1940.

Ellen

Date: Mon, 7 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Middle Class and High Status Ways of Eating

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

It seems to me that both the narrator and Emily Dunstable make fun of Mrs. Proudie's converzatione (sp?) in (I think) framley parsonage, but i dont remember mrs p feeling as though her skimpy fare was wrong (although she did feel as though miss d had misadapted her idea by making a rich social whirl. My memory (fading fast) is that the narrator, ion that section makes a pitch for relaxed middle class meals very much like the one made here.

By the way -- do we know who the Trollope readers of the time were? Demographiclally were they more like Mr. rubb than Miss M; that is did they have private incomes, know baronets etc. do we have a reason to think workers didn't read? It's sort of like beating an obvious drum -- Trollope's chaaracters are richer than dickens' were his readers also richer? or did they just wish to be.

Daniel Millstone

Date: Tue, 08 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Trollope's Readership

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

In response to Daniel,

There have been numerous books attempting to pinpoint and describe the various audiences for Mudie's Library and other part of the middling marketplace of novels. Speaking very generally, the readership was of the gentry class and above, but it also had lots of people below that who had the time and inclination to read (or be read to). The books often reflected an ideal people thought or assumed all aspired to or envied; I'd offer the idea that the presentation of the dinner party is intended to please precisely the sort of person who might see him or herself as above such strained behavior -- whether that be the type of person Mr Toogood in The Last Chronicle represents (a modest lawyer when you go to his house you get a good meal comfortably served wihout any phony recipes) or the type of person Plantagenet Palliser represents (just beyond caring, so above it). The satire is heavy handed caricature. Trollope does not seem to be worried about offending any readership here. In this it resembles some of the heavy caricatures in portions of The Warden.

The pioneering very readable book is by Richard Altick, The English Common Reader; a more recent book whose title I don't have at hand is Jonathan Rose's on common readerships of the 19th century. He tries to reach the working class reader. It's much harder because such people left little writing. But they did and could read. They had some portion of the evening and instalment publications and the spread of libraries and societies for improvement put into their reach books. Not all books. Hardy's Jude and some of Gissing's heroes lament their lack of choice and the types and outlooks they are served up. It's not true that only women read novels -- though some of them had more leisure.

A more scholarly approach (but very good, readable) is a book called Literature in the Marketplace. It has a wonderful article on the boy who dies so pathetically in Bleak House. It lists books in accordance with who sold them and which ones, goes over curricula in schoosl.

Very recently a book appeared which attempts to analyze Trollope's books from the point of view of some imagined group of readers as reflected in the middle class magazines which both produced instalments, advertised novels and other kinds of higher minded self- improving and just intellectually sound and educated books: Turner, Mark. Trollope and the Magazines: Gendered Issues in Mid-Victorian Britain. London: Palgrave Macmillan, April 2000. As I understand it (I haven't read the book only about it), this book attempts to show how Trollope's novels would play very differently between male and female readers of the time and concentrates precisely on those issues (many) which would show a gender faultline.

Miss Mackenzie may be one of those books where the general response of a reader will depend on his or her gender and sexual idenfication. But not all issues are gone into seriously by Trollope: for example, he presents as an intense given that Miss Mackenzie will be utterly obedient to John Ball -- except when he goes so far as to distrust her chastity (and then she doesn't object to his right to distrust her), she caves in utterly. Now in this overt reiterated almost obsessive demand for female obedience Trollope is different or over the top in comparison with just about every contemporary male novelists I've read. Going to look at readerships, imagined or read, is not going to help understand this or his use of it in different novels. In HKHWR, it's a coverup for the male talking about his sexual anxiety and demanding his wife imprison herself from all sorts of relationships; it's an analogous coverup in Kept in the Dark; but not here. There's no question about our Griselda's "purity:" yuk on that word, one of the most imprisoning and cruel words to be applied to women ever.

Going into readerships helps. I suggest the illustations of the novels reflect a female readership. But it only goes so far.

Ellen

Date: Wed, 09 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss M: Littlebath

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Yet more on what probably is not of that much interest -- though I rather think the place that Miss M comes to is of great interest. Trollope is a novelist who uses symbols, though they grow slowly. They are the result of places, houses, and landscapes and the social and psychological values that characters who find themselves in must deal with.

I went back to a few chapters in the books I cited, and came to the conclusion that as usual Trollope is amalgamating. The literal description of the street, the small assembly room, as angled could very well be Cheltenham. But the ambiance, types of people (hangers-on, desperate nobodies, people seeking power through religion) is what's found in the communities which grew up on the outskirts of the central city.

Miss Mackenzie shows her social innocence, isolation and desperation when she chooses such a place. The "in" people, the people with names, the powerful and well-connected went to the continent -- as we see the Pallisers do (Baden and such like places). She also shows where she fits in her niche. Her money is not endless -- and that's why Mr Rubb is a great danger to her. Her pension even when large something that needs to be watched. She is not young. Batheaston was the kind of place you'd find such a woman in. You could shine quickly at small expense because it was small. It's very hard to meet new people in London because it is so enormous and everyone living so anonymously outside their narrow family-, friend-, school- and job-networks. Rather like our modern world, no?

Ellen

Date: Tue, 08 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Dinner parties in Trollope

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Hi all. I have been sadly behind in my reading and am just now caught up with Miss MacKenzie, which I am enjoying. I believe the parsimonious dinner asked about is in Orley Farm; the wife hoards food in her room while serving her guests insufficient food, much to her husband's and guest's discomfort. I never read the short story Ellen referred to, by Thackeray, but would like to. I can only think of two other memorable disaster dinners, one in Shakespeare (come on, you all can guess that one), and one hilariously funny one in Booth Tarkington's Alice Adams. That one is akin to the MacKenzie, in that the mother of the family tries to put on airs to impress her daughter's suitor, with a hired person to serve, and all goes wrong. The Brussels sprouts smell, the ice cream melts in the summer heat, everyone is besides themselves by the time the misery ends. Pat (off now to dinner)

Date: Wed, 9 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie, Chapters 6 to 10: Anti-Rubb Still; Trollope and

Dinners 'a la Russe'

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I seem to be in a minority of one in respect to Mr Rubb. Personally I can no more feel sympathetic to someone who swindles me out of my money than I would to someone who knocks me over the head and takes it. Their businesses may be in great danger of collapse or their families of starvation, but this does not excuse their solving their problems at my expense. Still, let's move on to the rest of the novel.

Catherine's summaries of these chapters covers the action very clearly. We know that Trollope hated dinners 'a la Russe' , and he refers to them in Framley Parsonage and The Prime Minister, as well as his most detailed description in Miss Mackenzie. According to Mullen in The Penguin Guide these seem to have called for more courses with small portions of numerous elaborate - and often foreign - dishes handed around by many servants. The table was highly decorated with massive displays of flowers. In The Last Chronicle_ the solicitor, Toogood, promises John Eames that he will not be regaled 'a la Russe', but gets one of Trollope's favourite meals 'a leg of mutton and trimmings and a glass of port such as you don't get every day of your life'. About twenty years ago, there was a craze in the UK, and probably in the US as well, for serving small portions of food, prepared with what was supposed to be great skill and care. This had a pretentious French name, which has now gone entirely from my memory. It seems that this was some sort of revival of dinners 'a la Russe', and I am pleased to note that it appears to have gone the same way.

I agree with Catherine that the Balls are a dreadful family. The only one with any attraction appears to have been young Jack, the eldest son of Margaret Mackenzie's stout, middle-aged suitor. The latter appears to be most unattractive, and I agree that he seems to be looking for a moneyed housekeeper. The interesting feature is that Margaret seems to be in two minds about his proposal, and is only stopped from accepting it by Lady Ball's interference. It is interesting that Trollope appears to think that becoming Lady Ball would be a fair exchange for Margaret's fortune, but this is, I think, another example of his snobbishness.

'Miss Mackenzie's Philosophy' does give Trollope a chance to indicate that he realised that Margaret had a personality of her own, with her own needs and desires. Having given a surprising (for Trollope) display of her sexuality in the famous mirror scene, she thought over John Ball's proposal and then writes and rejects it outright. John is inclined to accept this, but his mother is still anxious for him to try again. We also see how Margaret's view of the Stumfold clique is greatly reduced, largely on the grounds that they are in the main not ladies or gentlemen. I am with Catherine in laughing at the concept of a lady dying rather eat with a steel fork, but one must assume that Trollope meant it. He was, however, referring to Miss Baker's views, rather than to those of Miss Mackenzie.

Chapter 10 deals with the question of the loan made to Rubb and Mackenzie. Although it is clear from Mr Slow's letter that Mr Rubb has acted dishonourably, Margaret decides to tell Mr Slow that she was aware of the situation, and 'My brother and his partner are welcome to the money'. When Mr Rubb turns up she shows him her letter, but not the one written by Mr Slow. Mr Rubb is disconcerted when Miss Baker appears, presumably because he had hoped to continue with the softening up process. But I must not go on ...

Regards, Howard

Date: Thu, 10 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie's balance & the Dreadful Balls

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I am just catching up with the reading of Miss Mackenzie and I am growing to like her more and more. She seems one of the most balanced of Trollope's women. She's not immune to the class feelings that make Mr. Rubb seem inappropriate, but she doesn't overvalue being a gentleman either. As she says to Miss Baker, "A man who keeps a shop is not, I suppose, a gentleman. But then, you know, I don't care about gentlemen--about any gentleman, or any gentlemen." And she would like to bring together Miss Todd and Mrs. Stumfold, while other ladies seem content to belong to one group or the other.

The Balls are a dreadful family, but she can sympathize with John Ball, struggling to support his nine children. (How terrible to be a Victorian and have nine children descend upon you with apparently no means of controlling the births. We forget how much more control we have over our lives now, and how much more comfortable that makes them.) Miss Mackenzie can sympathize, but she is not foolish enough to sacrifice her own life to make his more bearable. She has a good head and manages to steer clear of the most dangerous entanglements offered her--at least so far!

Adele

Date: Fri, 11 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Mrs. Tom Mackenzie's Dinner Party: Mr Grandairs

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Catherine, I loved this chapter too!

Trollope gave us another wonderful name in Mr. Grandairs. So great that at first mention I thought the character was using it in place of the hired butler's actual name. And what a mean, snotty wretch he is too. Very sadistic as Catherine mentioned in the episode holding the empty champagne bottle over the doctor's glass.

Sig, thank you for the reminders of Slow and Bideawhile in other books. I had forgotten the firm name.

Dagny

Date: Fri, 11 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Miss Mackenzie: The suitors

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

On Mr Rubb Howard wrote:

I seem to be in a minority of one in respect to Mr Rubb.

Well, no. I really liked Mr. Rubb in the beginning, but as I read on I am beginning to seriously distrust the man. Also, he seems a little "slick" to me, rather like the common public conception of a used car salesman. At first I thought he was deceived himself, and maybe he is, I don't know yet. But he is too pushy really. His many apologies don't ring true to me.

Miss Mackenzie has given her money up and looks on it as a gift to her brother Tom to help save his business. But this is no excuse for Rubb to continue hiding the truth from her. It only serves to make me wonder if Miss Mackenzie married him and he had control of her money if he would be then true to Tom and the business or if he would take her and the money and scarper.

On John Ball Howard wrote:

It is interesting that Trollope appears to think that becoming Lady Ball would be a fair exchange for Margaret's fortune, but this is, I think, another example of his snobbishness.

I read it differently, probably because I don't know as much about Trollope and his life. I thought that it was only the character of Lady Ball that thought so much of the family status and that Trollope was making her appear not only totally deluded but silly in the bargain. After all, Miss Mackenzie might have accepted Ball's proposal had it not been for his mother making such a fuzz and mentioning the carriage, etc. in addition to "what was owed." She defeated her own purpose

Dagny

Date: Fri, 11 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] The philoprogenitive Mr. Ball

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Trollope obviously means us to think ill of Mr. Ball in having 9 children to rear without his possessing the financial resources to fulfil his parental obligations. I think this intention may be assumed since the number of children is such a hyperbole - his need for a mother for his children could be just as acute with a lesser number.

However, I wonder just why he had so many. After all, birth control had existed for centuries, even if it achieved much greater efficiency (without resulting in the hoped-for dramatic reduction in teenage and other extra-marital pregnancies) in the twentieth century. Was it that women were averse to it or did not dare insist on it. Or did so many men in the Victorian era, wanting nothing to impair their connubial gratification, fail to offer such a resource, impervious to the risk to the mother or the family budget, in a way which would not be permitted to them by the professional ladies to whom so many of them also resorted? I can understand that with higher rates of infant mortality (although reducing under the scientific advances of the Victorian age) they would want to have some "insurance" in order to perpetuate the line - but surely nine is a bit over the top!

DRG

Date: Fri, 11 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Mr. Rubb's business ethics

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I suppose my use of the word "con man" with regard to Mr. Rubb came across as a little too strong. I think Rubb is self-deluded, but that does not mitigate his actions. Just look at what's going on on Wall Street now. How could the Enron fiasco have taken place? Because some people start down the slippery slope of self-delusion, self-denial, and pure selfishness. Enron is one example many people may have heard about, but I'm sure business fiascos like this happen all over the world.

I work at an investment management firm. Part of my day consists of 45 minutes reading The Wall Street Journal. Not a week goes by but that another story comes out of a business that collapsed on itself, leaving stockholders holding the bag. It is interesting to read how such disasters take place. Usually, things start going wrong when people start taking stop-gap measures to cover their asses, thinking that the problem is temporary, and that they can make up for a bad quarter. Usually, as the situation gets exponentially worse, the perpetrators get desparate, but at the same time more brazen with their lies and fraud.

In most cases, it seems to me that the person behind the financial shipwreck did not start out as a villain. Who gets up in the morning and thinks "Aha! I have a devious plan. I am an evil genius. What can I do today to further my nefarious purposes?" Surely, there are criminals who deliberately rob and cheat people with Ponzi scams and the like. But the majority of business people who get into a jam start by make one small moral compromise after another. Rubb is of this ilk.

There is a marvelous quotation that I can't quite remember that goes something like "No man consciously choses evil, but merely picks the course which he thinks will bring him happiness." Perhaps someone more well read than I can cite the quote.

We know that Trollope pulls no punches with his financial villains. Melmotte is at the high end of the scale. Lopez is less grandious in his efforts, but still a fraud. And then there is the character of (Forgot the name!!!) in the Barsetshire series, who gets into financial ruin and kills himself. Trollope shows us the inner workings of these characters, and to an extent, has empathy with them. Rubb does not get such treatment - we don't see his psychological workings. But we see those infamous yellow gloves. Rubb is after Miss Mackenzie's money, but he's no evil mastermind.

Rubb is pathetic, but in the end, somebody else is going to have to pay for his mistakes.

Catherine

Date: Fri, 11 Jun 2004

Subject: [trollope-l] Mrs. Stumfold & Trollope's Attitude towards Evangelicals

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

I've been thinking about Mrs. Stumfold in Miss Mackenzie and all that she represents. First, she certainly is a sister to Mrs. Proudie. She loves the low church and is on a continual militant crusade to perpetuate it. Trollope, as we have learned from many novels, has no use for the low church, and some of his most despicable characters, for instance Mr. Slope, adhere to it. I wondered if Mrs. Stumfold were a replacement for Mrs. Proudie, who went to a better world late in the Barchester series. But no. Trollope was writing Miss Mackenzie in 1864, and the Barchester series lingered on through September of 1866.

I think the answer is that Trollope was no friend of extremism. He cherished his religion, but he was able to give us a few decent people who belonged to other faiths. What Trollope disliked was extremism, either in politics or religion, which, of course, were very similar to him. Today, if he were convinced that Muslim extremists were behind many of the outrages of our own time, he would have supported Mr. Blair's views toward Iraq.

So back to Mrs. Stumfold: she is indeed a sister to Mrs. Proudie. She is moving in a course that cannot succeed. She will go to her grave believing herself to be a fighter on the side of her God and the righteous enemy of Catholicism, the High Church of England, Judiaism, Islam, and any other creed which might come to her attention. She probably sees herself as eligible for immediate entrance to Heaven, but there I cannot agree with her.

Sig

Mrs Stumfold: Another Hate-filled Monster Bully-Woman like Mrs Proudie; not quite as Soul- Withering and Life destroying as Lady Ball and Mrs Tom

In reply to Sig

I agree with Sig that Mrs Stumfold is another monster woman like Mrs Proudie. I see these women not as the product of some rational idea in Trollope nor even his prejudices against low church people. There are too many of them in his novels and not all are evangelical. In this novel we have Tom Mackenzie's wife and Lady Ball too. Trollope knows he has done this and so provides a tiny paragraph saying she is not a monster (to cover the tracks of this archetype which derives partly from male nightmares). Later in the book we get the grotesque freak show of the charity ball which is interesting to read against the depictions of Stumfoldian totalitarianism and the deadly horrible cruelties coming out of Lady Ball's mouth hourly.

Ellen