Date: Fri, 20 Oct 2000

To Trollope-l

January 12, 2001

Re: Ayala's Angel, Chs 1-6: Illustrations Which Attract

Although, as many of us have written, there is much adversity and some grimness in this opening sequence, as well as two orphans who no one much wants, who have no money whatsoever and could therefore end up in some highly unpleasant places, Robert Greary's first illustrations is pure romance.

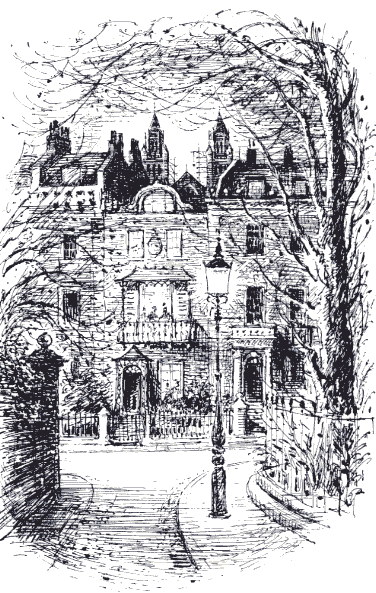

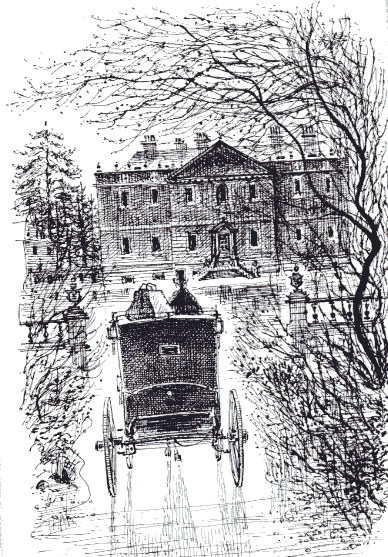

The frontispiece is this time a picture which belongs to the first chapter. The captain reads: 'The most perfect bijou of a little house at South Kensington'. The passage which the illustration refers to is brief but suggestive:

'But he had a taste for other beautiful things besides a wife. The sweetest little phaeton that was to cost nothing, the most perfect bijou of a little house at South Kensington . . . '

The rest of the passage does not describe the house, but is shot through with irony runs over the dining room, 'the simplest little gem for his wife' that 'might have been packed without trouble in his brother-in- law Tringle's dining-room', 'just a blue set of china' for his dinner table, just a painted cornice, just satin hangings, a few simple ornaments for his girls. The narrator wants us to remember such a few little simple things cost a great deal. I read Angela's posting today and find in this passage further reinforcement for our disappointment that Trollope ignores the artistry of the man's occupation -- and the tools of such a trade cost a great deal too -- to focus on the pretty material things with which he surrounds his diurnal physical life. The ironies, as Alice Thomas Ellis says in her introduction, focus us on the material ruin such sprezzatura towards money can bring.

What Trollope doesn't do -- much like Austen in her books -- is detail the house. Now this is not that typical for Trollope. In many of his novels he does describe a house or landscape slowly so as to build a picture of it up in our minds. Here he just leaves suggestive hints: the garden where they read their books, the breakfast nook. We are told the 'bijou' was red brick.

Greary imagines a small town-house (that's what we would call it in the US) sandwiched tightly inbetween two larger wider ones.

The technique recalls the later 18th century picturesque, drawings by Gainsborough which brought forth from later 18th century poets like Cowper, lines like "Italian light on English walls". It is lovely: 3 floors, a terrace in the middle (on which we see figures standing), a fancy sort of threshold (pointed arch over the top), lots of pretty bushes and trees. Upstairs there is a big window in the attic: perhaps the artist's studio. The town-house is set back in the picture; close to us is a street-lamp, a curving sidewalk (Hogarth's serpentine line is much on display), and then trees whose branches have a lose candelebra feel. A fresh breeze moves through this picture. Greary himself would not have minded living in this house -- nor were Ayala, Lucy, their mother, Adelaide, nor Edgar Dormer himself without gaiety and loveliness here. He has made the two houses on the other side of the Dormer house are lined darker; their windows are filled with dark shadows while the windows of the Dormer house are left white (the artist made no lines). It was a bright place.

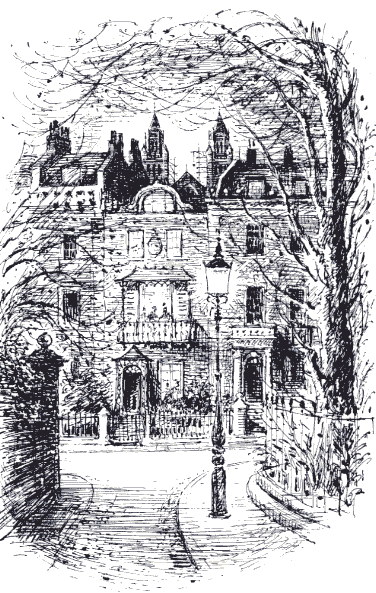

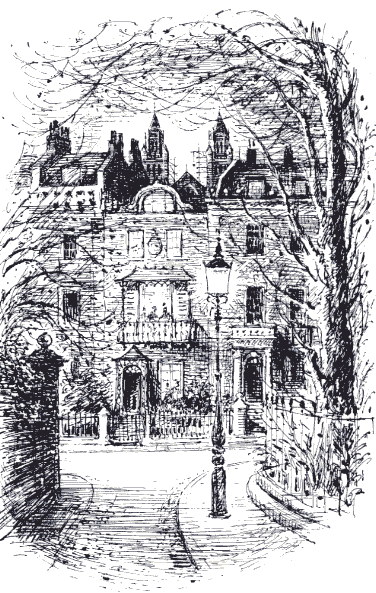

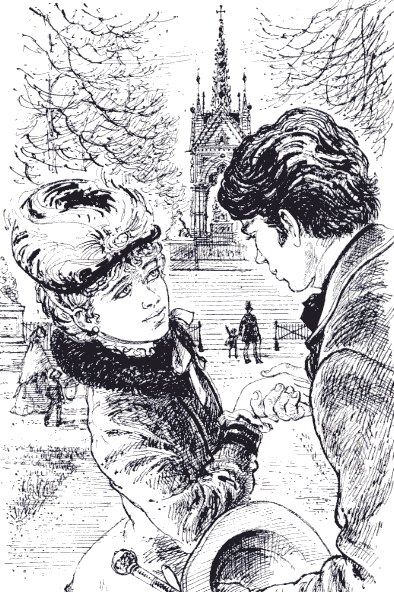

The second illustration brings us one of the young girls who lived in this house, and the young man whose acquaintance with her father brought her to his attention. It too emphasises the romance of the book. The caption is 'There was the same look as he took his leave', and the illustration is sandwiched between the verbal text which this sentence climaxes.

Robert Greary has chosen to picture the place in the park where Lucy walks each day, where she saw Isadore Hamel that first day, and then, perversely, unaccountably to herself, avoided him.

Trollope's text shows Lucy's mind deeply intent on Ayala's troubles:

"'Oh, Tom -- that idiot Tom!" And another word about Augusta. 'Augusta is worse than ever. We have not spoken to each other for the last day or two'. This came but a day or two before the intended return of the Tringles. No actual day had been fixed . . . (Folio Society Ayala, introd. ATEllis, Ch 4, p. 30).

Lucy worries that Ayala is 'subjecting herself to great danger'. What danger? in this week's installment, our narrator defines it for us as showing her discomfort, alienation, and as refusing to buckle under 'humbly' ('There was, [Lady Emmeline said], no gratitude in Ayala. Had she said that there was no humility she would have been more nearly right. She was entitled, [Lady Emmeline thought] to expect both gratitude and humility', Ch 7, p. 51). As Lucy walks on, absorbed,

'of a sudden, Hamel was close before her! There was no question of calling to him now -- no question of an attempt to see him face to face. She had been wandering along the path with eyes fixed upon the ground, when her name was sharply called, and they two were close together. Hamel had a friend with him.'

He has a friend with him, Lucy feels she can only bow, mutter, pass on, look pleasant, but 'he was not minded to lose her thus immediately, "Miss Dormer", he said, "I have seen your sister at Rome. may I not say a word to her?"' 'In a minute' he leaves the friend, and is walking by Lucy, lets her understand her aunt had not been 'very gracious' to him in public, but he smiles and elicits the information that she lives with the Dosetts 'at Kingsbury Crescent, but that he may not call be able to call 'as her aunt did not receive many visitors -- . . . her uncle's house was different from what her father's had been'. He comes to the point: "Shall I not see you at all?". She has no presence of mind to ask where he lives in London, what he does, and can only repond "'Oh yes . . . perhaps we may meet some day", but when he immediately takes her up on that, '"Here?'", she darts away mentally from what some might consider as assignation; he, sensing this, brings out the emotional and literal truth of their situation which neither can accept:

"'I have thought of you every day since I have been back", he said, "and Idid not know where to hear of you. Now that we have met am I to lose you again?" Lose her! What did he meant by losing her? She, too, had found a friend -- she who had been so friendless! Would it not be dreadful to her, also, to lose him? "Is there no place where I may ask of you?'"

Her aunt's; he may come to her at Lady Tringle's when Ayala is back. Again he is the alert one, and gets the address, and she then closes the precious moment of communication:

'"I think I had better go now", said Lucy, trembling at the apparent impropriety of her present conversation..He knew that it was intended that he should leave her, and he went. "I hope I have not offended you in coming so far".

'"Oh, no." Then again she gave him her hand, and again there was the same look as he took his leave.

Here is the illustration:

The illustration brings us the two young faces close up; we can see their bodies about three-quarters of the way down. They are framed by a picturesque, semi-melancholy rendition of the park and a few figures at a little distance from them. Again the technique recalls the 18th century picturesque: the bare trees are many curling, sweeping lines; it's all lightly sketched in: stairs leading to the monument in the distance, a man and child walking up; on the other side a woman with another child. Lucy's face is just above the center, and drawn so that we see her eyes looking intently into that of a handsome young man who looks back into hers. Greary does not register the anxiety and embarrassment, the sense of some deep distress in Lucy as she struggles to respond to the young man whom she clearly is already deeply attached to; but the face is filled with earnestness. It is after all that last moment, her response to his last look. Their hands are well done; they hold tight just below the center of the picture space. They are visualised according to traditional romantic values: she is blonde, blue-eyed; her hat is a pancake with veils clasped onto a brooch; she has a ribbon at her heck, a close-fitting upper jacket. He has dark wavy hair, a ribbon-like tie; at the bottom of the picture we see a hat, and cane. He is all the gentleman, she the lady.

Trollope's language is exquisitely gracious. Isadore is anything but gauche in the manner of Tom Tringle. In the second illustration, Greary has visualised one of Trollope's thematic contrasts: the male who has savoir-faire and is perhaps overrated for gracefulness and presence of mind, though from the content of Isadore's words we see he means nothing clandestine though he is determined to renew the relationship. In both he has brought forward a poignant vein in the book: the Dormers, this art world makes of life something worth the living -- as long as enough money can be made to come in.

Cheers to all,

Ellen Moody

Re: Ayala's Angel, Ch 7-12, Pictures: Ayala, Cornered and then Ejected (I)

This week's two illustrations focus us on Ayala's story: she is at the center of of both.

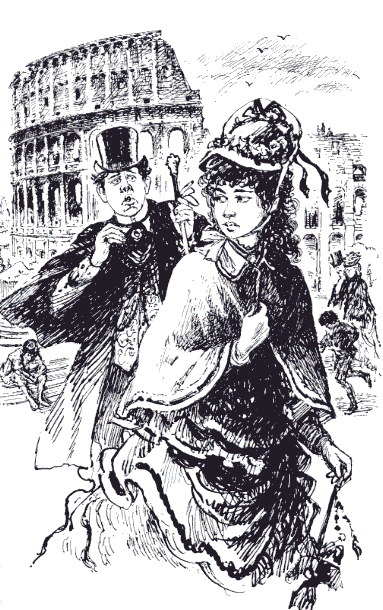

Geary has taken off (or visualised) Tom's words in the first. The caption reads: "'Ayala, I am quite in earnest'."

Tom and Ayala are pictured against "the walls and arches and upraised terraces of the Coliseum". She fills out most of the picture space, is to the fore, at the center. Geary has followed Trollope in imagining her appearance in contrast to Lucy's: where Lucy was blonde, Ayala has dark hair; where Lucy's hair was wavy, Ayala's is all curls; Lucy's hair is tucked under her collar; Ayala's is long, flowing, comes down past her shoulders (for Victorians long hair on a woman was sexy -- remember the Pre-Raphaelites' pictures), yet it is not overabundant (so she's chaste, young); her eyes are dark. She is dressed in much prettier clothes, all furbelows. However, instead of looking into the eyes of the young man, half-eager, anticipatory, outward, trusting (as Lucy was to Isadore Hamel in last week's picture), she turns away. Her hand is on her small jacket, holding it closed. She faces us, but is at the same time averting her body from Tom, tightening up; her eyes look slightly desperate, a melancholy-resentful look in them as she turns her head only somewhat around, not to face but to acknowledge a large young man who is in the half-distance of the picture and is quick-stepping after her. Tom is pictured as heavy, a very round face; he is dressed very expensively; we do see a jewel in his collar, and his cane has a fancy top. He is not conventionally handsome; it's hard to put into words why this is; perhaps it's the down-turned features which look distressed and eager and anxious. His eyebrows go up; he is rushing after her, appealing to her on an emotional basis. There are small boys distance playing on and in front of some coliseum steps; a couple passes by.

The text to be meditated (facing the picture) gets its tension from Ayala's cornered attempt to slither away:

"'Say one nice word to me, Ayala'.'I don't know how to say a nice word. Can't you be made to understand that I don't like it?'

'Ayala'.

Why don't you let me go away?'

'Ayala -- give me -- one kiss'. Then Ayala did go away, escaping by some kid-like manoeuvre among the ruins, and running quickly, while he followed her, joined herself to the other pair of lovers [Gertrude and Frank Houston, just beyond the picture frame], who probably were less in want of her society than she of theirs. 'Ayala, I am quite in earnest', said Tom, as they were walking home, 'and I mean to go on with it'

Ayala thought that there was nothing for it but to tell her aunt. That there would be some absurdity in such a proceeding she did feel -- that she would be acting as though her cousin were a naughty boy who was merely teasing her. But she felt also the danger of her position (Folio Society Ayala's Angel, pp. 53-54 and facing illustration).

The illustration functions to create sympathy for Ayala, to make us feel her sense of a desperate animal cornered. While Tom looks vulnerable, in need, emotionally open to hurt, he is insisting, moving in on Ayala (the current US slang for this, a cruel term for the one who woos, is 'hitting on'). The effect is to justify her decision to write to Tom to beg him to stay away, and then when she gets a letter in response -- speak to her aunt. Even if both moves show naivete about how people will seize as an opportunity what is not meant that way (particularly in courting, sometimes to say 'no' is for the one wooing, at least something to respond to) and how they cannot be converted easily to another perspective, especially if it comes from someone they already have reason to want to revenge themselves on, we see how Ayala does have to do something. He will not leave her alone. He 'means to go on with it'.

I thought of yet another male character whom Trollope dramatised as wanting a female, and whom their shared community pressures her into accepting: Harry Gilmore in The Vicar of Bullhampton. In that earlier book (1869-70), Trollope treated this situation in detail, with careful nuance, delicacy, and emotional power: depending on your perspective Gilmore emerges as neurotic, ugly in his perseverance, and an example of how women were oppressed by their society in this period, and Mary Lowther as unsympathetically vacillating, turned off because he is just not sexually attractive to her, but at the same time the caged untame bird.

The only thing for it is to get into another cage. And that's what is done for Ayala.

I'll describe the second illustration in a separate posting.

Cheers to all,

Ellen

Re: Ayala's Angel, Ch 7-12, Pictures: Ayala, Cornered and then Ejected (2)

The second illustration visualises Ayala's arrival at the Dosett house. The words visualised -- taken off from -- are Reginald Dosett's to his niece upon her half-tearful arrival: she "was hardly able to repress her sobs as she entered the house". He and his wife have this time attempted some preparation and welcome to the incoming niece, and Trollope gives him these words: "'My dear', said the uncle, 'we will do all that we can to make you happy here'.

Ayala is still in the center of the picture space, but this time she does not loom largely over us, and faces away. We see her at a slight distance, from the aback, leaning on a an awkward uncle, who gingerly attempts to touch one of her arms as she hides her face in a handkerchief. She wears the same pretty outfit we saw at the coliseum.

However, the emphasis of the illustration is on the house as too small and overdecorated, or filled up with objects in just the way such a fringe upper middle class house would have been in this era. A good deal of the picture space behind Ayala is taken up by a narrow staircase up which two workmen are carefully trying to fit a large trunk. How they will turn it about to get up the next rung is not clear. On the floor in front of Ayala is a further large trunk, another smaller one, a hat box'. Her ruffled dress seems to fill the landing space a bit too fully. The housekeeper whom Trollope mentions in passing stands at the foot of the stairs watching somewhat anxiously. She is in the sketchy style of a figure who is secondary but emblematic through her posture. We don't see Aunt Dosett or Margaret clearly at all: she stands in a threshold to a room at the end of a hall which goes under the stairwell. All we can tell is that she is standing apart.

The style is light, something in the vein of 18th century picturesque so we don't get the exquisite detailing that G. Houston Thomas did for his illustrations of houses for The Last Chronicle of Barsetshire, but enough is given for us to see all the many lamps, some in fancy holders on the walls, one on a table, fringe cloth covering tables, losts of picures, a mirror, designs on a carpet, on the wallpapers. To the right of Uncle Reginald and Ayala we see the opening threshold to another room; there we glimpse very heavy curtains pulled back over a large window, yet more curled heavy tables, lamps, pictures (Folio Society Ayala's Angel, p 76 and facing illustration).

Here is a pair of people who are together giving their all to maintaining a solid-looking position they don't quite have the funds to maintain. Unlike the Dormers who lived from day-to-day and were content to do without all the solidity, the Dosetts are also trying to pay down their debts, provide for pension and insurance in their respective old ages. I imagine many older readers of this would have identified with the Dosetts. The depiction of the uncle makes him too young (this is the way with the 19th century illustrators too), but his clear sympathy and lack of aggressive posturing makes him sympathetic.

However, Ayala is not the bad guy; she is the outcast here; the one ejected from a previous home because she 'didn't suit', didn't 'hit it off' with its females. Further, the narrative told by the pictures and by the text in the next couple of pages tells us one of the reasons for her ejection is her rightful rejection of Tom. Why should she accept him as her husband? Trollope's novels repeatedly dramatise this conflict between selling oneself to suit others and gain a respectable safe position in society and marrying to gain a companionate affectionate relationship in which one may find individual fulfillment for real. In this novel he has strengthened the depiction by showing us how close to the streets the girl who refuses can be.

I like Judy's parallels with Austen's Mansfield Park. Fanny Price has of course been brought up by the overtly mean Mrs Norris to understand that she had better be humble. Early on in the book when asked if she likes Fanny, Lady Bertram says, oh yes, she 'always found her very handy and quick in carrying messages, and fetching what she [Lady Bertram] wanted' (Penguin MP, ed TTanner, Ch 2, p. 56). Maybe Ayala understood much better than any of us how she would be used if she didn't protest in some way against becoming the fetcher and carryer. (I suddenly remember an African-American character in a TV situation comedy in the US long since blessedly off the air -- it had a character who was a sort of Uriah Heep; his name "Step-and-Fetch-It"; that's how he got through life.) When Fanny Price rejects her young man, all are horrified and she soon finds herself being given the 'medicine' of a return to a very poor Portsmouth house.

This illustration and its immediate text are softer in overt tone than Austen's hard MP. Nonetheless, Aunt Margaret comes in pretty quickly to make sure that this time there will be an appearance of congeniality and to start the shared dutiful life together. The change of name is an unconscious handle, a way of playing emotional blackmail that insists on Ayala's compliance. And of course Ayala now has learned she can be ejected and will 'behave' much better as regards the errands. But not as regards Tom. Why should she? Aunt Dosett's words justifying Tom's right to keep on suing, and against Ayala's refusal of him remind me of Lady Bertram's to Fanny (you have a duty, dear Fanny, to close with such an offer) of which the narrator says (very sarcastically), they were the only advice Lady Bertram ever gave Fanny in all the years she was there.

Cheers to all,

Ellen

Date: Sun, 28 Jan 2001

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Subject: [trollope-l] Ayala's Angel, Ch 7-12, Pictures

Ellen, thank you for your posts on the illustrations. I was especially glad to hear a description of Tom as his looks were very vague in my mind.

I also really enjoyed the description of the movers trying to get Ayala's trunk up the narrow staircase. I noticed during the reading of the book how crowded Ayala's room was after she unpacked her belongs. Much more so than when Lucy was there since Ayala had acquired so many more items (in addition to not being as organized and neat as Lucy).

Dagny

Date: Sun, 28 Jan 2001

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

Subject: [trollope-l] Ayala's Angel: Reading Illustrations

This is to thank Dagny for her kind encouragement.

I am interested in book illustration, an area which includes a way of reading a book which has been partly lost -- at least to adults. The Victorian period has been called 'the golden age' of book illustration: publishers put money into the reproduction of illustrations because when they were good, they helped sell the book. Good artists participated because it was money on the side: an Edgar Dormer would have seen in book illustration a way of helping to keep the attractive lifestyle of his family in his little bijou afloat in the way of Millais and other Pre-Raphaelite and Idyllic artists and the various still well-known caricaturists of the period (e.g, 'Phiz' and before him Cruickshank). The French artist, Gustave Dore, made a handsome living making beautiful illustrations for classics in this period.

The Victorians also 'read' oil and other paintings as stories, and an interest in Victorian 'realistic' painting has been burgeoning in the last two decades, witness the number of museum shows of such pictures.

This partly relates to our submerged thread on buying Trollope's texts in different editions. I go out onto the Net every once in a while to seek inexpensive ($20-$25 is about what I am willing to pay) used Folio Society editions of Trollope's novels. Recently, I landed a Kellys and OKellys and am now on the hunt for a Castle Richmond. Castle Richmond was translated into 5 other languages in its first year of publication. Its topic -- the Irish famine -- is part of its compelling nature. I own both these in the Oxford Classics paperbacks, and Castle Richmond in a Dover, the former of which have the good introductions and notes I always want. But no pictures. The other day I almost secured to myself at a price of about $15 R. H. Super's Ann Arbor edition of Marion Fay. It is the first time since the original publication of the book that anyone has reprinted the full set of William Small illustrations that were printed with the book. However, I was thwarted -- and for the third time; that is, for three times in a row, I have tried to buy this book and someone had just snatched it up before me. I shall keep trying.

Cheers to all,

Ellen Moody

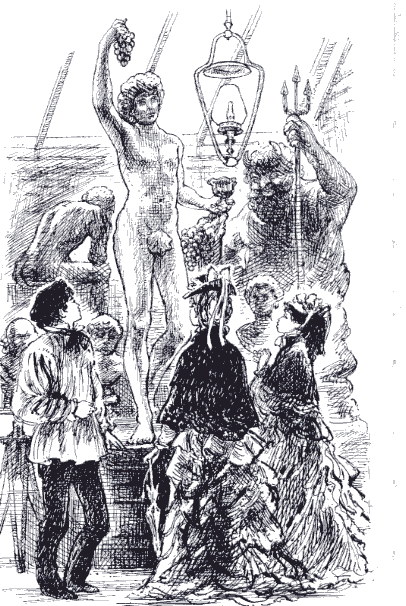

Re: Ayala's Angel, Chs 13-18, Pictures: At the Ball

In the Folio Society edition of Ayala's Angel, this week's 6 chapter instalment contains but one illustration, and we do not see Jonathan Stubbs in it. Instead he hovers just beyond reach; his the eye that sees Ayala with us. Geary teases us, works up expectation by depicting the elderly gentleman from whom Stubbs moves in to save Ayala rather than our chivalric knight himself. Stubbs is just beyond the picture frame. This week's picture does reinforce last week's: again we have Ayala dismayed, attempting to escape a male she doesn't want and sees simply as importunate.

The caption runs: "It was in his eye, in his toe, as he came bowing forward". What was? Well, as the text says, his desperation, his sense of alienation, difference from the those surrounding him -- or them both -- whether from age or personality structure, we are left to guess. The "aged gentleman" ("over forty"!) with whom she has "manoeeuvred gently through a quadrille", and who has asked her "two or three questions to which she was able to answer only in monosyllables," after which he "ceased his questions, and the manoeuvres were carried on in perfect silence", has come within view of her as she sits near "the wings of the Marchesa ... in undisturbed peace:"

"Then suddenly, when the Marchesa had for a moment left her, and when Nina had just been taken away to join a set, she saw the man of silence comign to her form a distance, with an evident intention of asking her to stand up again. It was in his eye, in his toe, as he came bowing forward. He had evidently learned to suppose that they two outcasts might lessen their miseries by joining them together. She was to dance with him because no would else would ask her" (Folio Society Ayala's Angel, introd ATEllis, Ch 16, p. 123).

We see a small man, thin. He takes up a space just left of the central picture space. He has a (I hope everyone will realise I don't mean in any sense to endorse the conventional depiction of so-called ugliness in this and any of these illustrations) a rounded face perhaps meant to recall that of a monkey. His nose is prominent and rounded. His hands are clasped together in a praying-hopeful position; his features are drawn downwards. Behind him we see many many figueres, some closer, some farther, all in very fancy ball dress, some walking along an elegant stairway, others in a hall, still others looking ready to dance. Chandeliers, rich velvety curtains, a small group of musicians provide a frame, and looming large to the fore, in front of us, once again Ayala, this time holding her fan over her face to guard it from the unwanted elderly gentleman so eager to come over to her. Her hair has flowers; she is elegantly got up, with a black velvet ribbon at her neck; one white- glove hand pulls slightly at the frills on her bosom. The expression of her eyes is dismayed. (illustration facing p. 124). It's clear she cannot see farther than her own ego. The young are often without empathy.

What interests the reader is the long section of prose which intervenes between this illustration and the elderly gentleman who sees Ayala as another outcast -- we are told her dress is not quite up to par; we are told that her time at Kingsbury Crescent has somehow or other entered into her soul, and she can no longer enter into the evening as once she could from the bijou. I suggest she is a sympathetic figure because she can no longer pull off that silvery-cold banter of frivolty which the text suggests is required of her.

Perhaps this aura was what brought Stubbs over to her, perhaps the picture of the pathetic male -- as well as Stubbs's friendship with the Marchesa and her prettiness. Intriguingly, it is in this long intervening passage between the description of the elderly man and the illustration that through Trollope's words we first glimpse Jonathan Stubbs in action:

She had plucked up her spirit and resolved that, desolate as she might be, she would not descend so far as that, when in a moment, another gentleman sprang in, as it were, between her and her enemy, and addressed her with a free and easy speech as thought he had known her all her life. 'You are Ayala Dormer, I am sure', he said. She looked up into his face and nodded her head at him in her own peculiar way. She was quite sure that she had never set her eyes on him before. He was so ugly tha she could not have forgotten him. So at least she told herself. He was very, very ugly, but his voice was very pleasant. 'I knew you were, and I am Jonathan Stubbs. So now we are introduced, and you are to come and dance with me" (p. 123).

Note he is not named at first: just "another gentleman". Note the references to dancing in silence, to strain. The first couple makes me remember Austen's Elizabeth Bennet and Darcy dancing together for the first time. Alas, Jonathan is no tall dark and handsome man. Yet despite his ugliness -- which is apparently to be epitomised in his having ruby red hair, a thick red beard, not silky, but bristly, with each bristle enormous, and an enormous mouth -- his suave dancing is only matched by his bright eyes, good humour and and wit. He tells her hers is "an out-of-the-way name"(knowing full well she objects to his plain first one and unpoetic, ungraceful last); that perhaps he is a rogue, knew her father, but that he "likes Tom Tringle in spite of his chains", and on another night, proceeds to make a play enchanting by his witticisms. Too bad we are not told these -- Jane Austen tells us Henry Tilney's who is described as very plain -- not "hideously ugly" -- Trollope does rub it in.

It is later that Ayala objects to Stubbs's lack of a Werther-faced sublime melancholy, and sees him as "a great tame dog", something Catherine Morland never compares to her hero. At this point our Colonel is just filled with sparkling wisdom, and sums up what a mature perceptive and somewhat cynical older man's mind would make of Ayala's behavior to her relatives and theirs to her thus far ("you don't like poor Traffic because he has got a bald head ... your cousin was jealous becuase you went to the top of St Peter's ...).

She dances many times with him; he is the partner of the evening. I suppose we might say (being dialogic) that this week's illustration stands for what Stubbs saw as he closed in on his young prey. He was "even in Rome" when she was. Of course he was. Like Austen's Tilney, as "male tutor" to a delectable "female pupil", he voices the attitudes of the author. It is a charming scene, one filled with a curious sympathy for the foolish girl who doesn't know what men can be and what to look for:

"'Was it true about the young lady who married Mr Montgomery de Montpellier and was thrown out of a window a week afterwards" (p. 126).

Well, not literally.

Cheers to all,

Ellen Moody

Re: Ayala's Angel, Chs 19-24, Picturing an Uncomfortable Ayala and Colonel

This week's illustrations put before our eyes an Ayala who is (in the modern parlance) kicking against the pricks, the prick in this case being Aunt Margaret, and a Colonel who has walks about disgruntled, unhorsed (which is to say unmanned) and with his feet in sopping wet boots. They are meant to be comic pictures.

The caption of the first is Mrs Dosett's resort to an ultimate rationalisation, a cant she probably believes in, but which, amusingly, doesn't faze Ayala: "'You are flying in the face fo the Creator, Miss', said Aunt Margaret, in her most angry voice. Ayala has just come back to Kingsbury Crescent, and to spend her life weighing joints of meat, pricing butter, and thinking about the wash, to be asked wholly to fill her mind with such struggling grates on her nerves. The outburst is actually triggered by Ayala's reference to her uncle's smelly gin:

"'I hate mutton bones', she said to her aunt one morning soon after her return.'No doubt we would all like meat joints the best', said her aunt, frowning.

'I hate joints too'.

'You have, I dare say, been cockered up at the Marches's with made dishes'.

'I hate dishes', said Ayala, petulantly.

'You don't hate eating'.

'Yes, I do. It is ignoble. Nature should have managed it differently. We ought to have sucked it in from the atmosphere through our fingers and hairs, as the trees do by their leaves. There should have been no butchers, and no grease, and no nasty smells from the kitchen -- and no gin'.

This was worse than all -- this allusion to the mild but unfashionable stimulant to which Mr Dossett had been reduced by his good nature. 'You are flying in the face of the Creator, Miss', said Aunt Margaret, in her most angry voice -- 'in the face of the Creator who made everything, and ordained what His creatures should eat and drink by his wisdom'. 'Nevertheless', said Ayala, 'I think we might have done without boiled mutton' (Folio Society Ayala's Angel, introd. AEThomas, Ch 21, "Ayala's Indignation," p. 163).

This is funny in all sorts of ways, some of them would bother the Rev Norman MacLeod's readers (he of Good Words). It makes me remember one of Austen's character's comment in Catherine, or the Bower when said heroine has a toothache: "I wish there were no such things as Teeth in the World; they are nothing but plagues to one, and I dare say that People might easily invent something to eat with instead of them'".

What Mrs Dosett seems unable to fathom is that a young girl doesn't want to hear about this sort of thing at all.

The illustration is not quite up to the picture because Mrs Dosett doesn't look wrathful so much as upset and perturbed. Ayala too lacks witty wry indignation and the subversion of the reductiveness to the particular. She looks down in a kind of stillness at her hands. Not sullen, just withdrawn. However, the room is beautifully done: the two sit at a table; they are sewing. There is an old-fashioned gas or oil lamp between them and a basket filled with sewing apparatus. Behind Aunt Dosett is a heavy mantelpiece, overcarved, with a clock inside a glass case. Plush heavy furniture everywhere, crowding them in. The back of Ayala's chair is prettily carved. We see a window at the right; it has a fringed curtain, and beyond it we glimpse leafless trees. Aunt Dosett wears round little glasses over which her eyes peer at Ayala; she has a shawl; her neckline is superhigh with a brooch. Ayala has the same black ringlets, and what looks like the same dress we saw in the park. She looks very young, a thin chest, high neckline and brooch too. Greary means to convey frustration with no outlet (illustration facing p. 164)

It is after this scene that Aunt Dosett takes her revenge by refusing to let Ayala go; when she is asked why, she reminds Ayala of her complain about "bones of mutton" (p. 165).

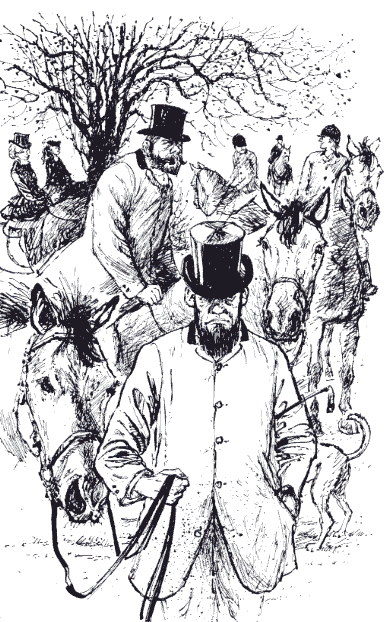

The caption of the second is "The Colonel with his boots full of water". The moment pictured is a little while after the Colonel's horse balked, jumped into a pond, and the Colonel is disgruntled, nonplussed, because he's left behind. The passage from which the line is taken is as follows:

"When Larry, with the two girls, were just about to enter the ride, there was old Tony standin gup on his horse at the corner, looking into the covert. And now also a crowd of horsemen came rushing up, who had made their way along the road, and had passed up to the wood through Mr Twentyman's farmyeard; for, as it hapepned, here it was that Mr Twentyman lived and farmed his own land. Then came Sir Harry, Colonel Stubbs, and some others who had followed the line throughout -- the Colonel with his boots full of water, as he had been forced to get off his horse in the bed of the brook. Sir Harry, himself, ws not in the best of humours -- as will sometimes be the case with masters when they fail to see the cream of the run" (Ch 24, "Rufford Crossroads", p. 189).

Here is the illustration:

We see a scene of what looks like people milling around on horses. They don't seem to be riding hard. In the back a wintry tree (leafless). Near it to the left are two women in riding outfits. Perhaps Ayala and Nina?. To the left are men in riding outfits, one man turns to speak to the other. To the front of the picture is Stubbs, very large, and just behind him, slightly smaller Sir Harry. Harry looks very heavy to my eyes, on a big heavy horse. His eyes are grim looking, slits. He is bearded and wears a top hat. Stubbs looks out at the world from under another top hat. He is probably meant to be homely: his nose is flat, his face fattish, his lips are downward in a frown. He has a bristly beard His ears are a bit prominent. He's not fat, but then he's not thin either. His jacket seems simply to hang on him as he holds the rein of a horse which follows him close behind. Amusingly the horse has a bristle of hair between its ears which resembles Stubbs's. The name Stubbs suggests something bristly, something prickly (deep buried is perhaps a salacious or shall I say pointed pun).

Two unromantic pictures for two unromantic moments. And yet the scenes are not simply prosaic: they are about wanting something you didn't get, about defeated desires to become or live out some yearned-for admired image.

Cheers to all,

Ellen Moody

Re: Ayala's Angel, Chs 25-30, Pictures: Landscape (I)

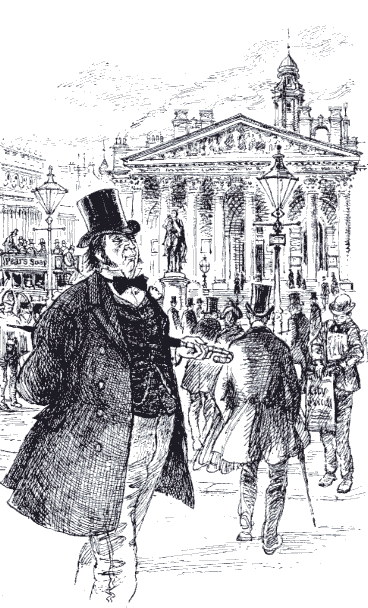

This week's pictures take us away from the central characters of Ayala and Lucy. All but one of the pictures thus far have visualised either Ayala or Lucy at some dramatic point of the story. The first of this week's return us to the perspective of the frontispiece: we have a picturesque take of a London street. The second shows us Sir Thomas talking to his coachman.

The caption for the first is: "On the next morning she was taken back to London and handed over to her aunt at Kingsbury Crescent". Geary has chosen the moment afterwards. Ayala's good time came to a crashing end when she was forced to realise that the reason she had been invited to this lovely place was its owner (Lady Albury) had a close relationship with a man (Colonel Stubbs) who wanted her for his wife. Suddenly the gay careless time, with no strings attached, contains a demand; something is wanted of Ayala in return. Worse, they are really serious about it. All the people in the house tell Ayala she has no right to refuse unless there is someone else she loves. When she says she wants nothing, has expected nothing from him or any of them for real, she is told:

"My dear, I should not take the trouble to tell you all this, did I not know that he is a man who ought to be accepted when he asks such a request as that" (Folio Society Ayala's Angel, Ch 26, p. 206).

Walter Houghton in his Victorian Frame of Mind discusses how young middle class girls were educated from early birth to regard marriage as a financial arrangement, how they were severely discouraged from an admission of sexual feeling on their own part which would preclude their marrying someone they were not attracted to. The irony was that the only excuse admitted was "attraction" to someone else, but that attraction had to be couched as a committment on both parts to marry. An engagement or near engagement would do; nothing else. That's why the characters keep asking Ayala if there is someone else. In Ayala on top of this Jonathan Stubbs has been presented as ideal husband material emotionally, intellectually and morally. Really all the fool girl objects to is his lack of sex appeal and name. But that "all" is one of the cruxes of the novel, one of its interests: what exactly is the "angel of light".

I throw the question out to anyone interested in picking it up? What exactly is this ideal man that girls dream over, the type movie producers look to hire when they are finding the actor to fill the "love" role in movies. What qualities is the chosen male supposed physically and visually to project? It's clear that Stubbs, Tom Tringle, and Traffic don't project it, and Hamel and Frank Houston do.

The picture's caption follows hard upon a dialogue with Mr Twentyman -- who is another male in the book who does not project this "angel of light" image. We are to remember him from An American Senator, a plain, home-y man, not quite the gentleman, it was his anguish at Mary Masters's refusal of his marriage proposal that took up much of the space of one of that book's plots. Trollope's novels intertwine and we could read Ayala's Angel as at some moments not quite a sequel to An American Senator but taking over some of its characters so as to fill out a corner in a new tapestry. We are told of how happy Twentyman is in this dialogue, how he just loves to have a wife and baby, how fulfilled is his existence; we are told of foxes and hunting, and the vigorous outdoors, but we are also told the atmosphere of all this has palled for Ayala:

"The day, in truth, was not propitious to hunting even. Foxes were found in plenty, and two of them were killed within the recesses of the wood; but on no occasion did they run a mile into the open. For Ayala it was very well, because she was galloping hither and thither, and because the day was over, she found herself able to talk to the Colonel in her wonted manner; but there was no glory for her as had been the glory of Little Cranbury Brook. On the next morning she was taken back to London and handed over to her aunt in Kingsbury Crescent without another word having been spoken by Colonel Stubbs in reference to his love" (p. 209, and illustration on reverse side of page).

We see a lovely lovely street. The same 18th century picturesque forms for ttrees and sky, the same sketchiness for the elegant buildings lining the streets, the same passers-by that we saw in the opening picture and in the depiction of Lucy's meeting in the park with Hamel dominate the whole. We don't see Ayala. We see an expensive elegant carriage driving along the way. There is a dainty looking woman in frilly dres and hat holding an umbrella over her hair standing near the carriage looking into the window as it moves by. The lights on the street, under the doorways, a woman standing near the right edge of the picture, larger than the rest, also carrying an umbrella, with a dog on a leash, all sorts of suggestive lines for symmetrical windows, balconies, a church in the distance seen over another far row of houses, lend a quietude to the scene. We see the horse who pulls the carriage from an angel. It is "afterward".

Why do some woman think they want an "angel of light"? What is an "angel of light"? The title of the book suddenly strikes me as importantly ambiguous -- as well as an allusion to Ayala's perceived sense of one of its sina qua non characteristics (according to our ironic narrator): he must have that "sublime, sallow, Werther-faced" element in his countenance as well as conventional handsomeness.

We could turn the tables. What do men want of a woman? Why is Ayala such an adorable decoration? Why do these men all run after her? It's not just her prettiness. What gives sex appeal? The landscape Geary offers is very human, filled with a feeling of an ideal setting human beings seem to long for, dream of. Why?

Ellen Moody

Re: Ayala's Angel, Chs 25-30, Pictures: A Fatally Crippled Horse (II)

Geary's second choice is similarly indirect. We are not given the scene where Gertrude writes her letter to Frank, proposing to elope with him, nor are we given the scene where her spiteful sister, Augusta, steals the letter from the mailbox and gives it to the father; we are not given Sir Thomas contemplating this picture gratified the elder daughter has so well known her "duty". No we are given a picture of the coachmen telling Sir Thomas how Mr Traffic has destroyed a horse by his inability to drive the family carriage down a rocky street. The caption reads: "'Mr Traffic brought her down on Windover Hill, Sir Thomas'". Here is the whole contextualised passage:

"'If you please, Sir Thomas', said the coachman, hurrying into the room without the ceremony of knocking -- 'if you please, Phoebe mare has been brought home with both her knees cut down to the bone'.'What!' exclaimed Sir Thomas, who indulged himself in a taste for horseflesh, and pretended to know one animal from another.

'Yes, indeed, Sir Thomas, down to the bone', said the coachman, who entertained all that animosity against Mr Traffick which domestics feel for habitual guests who omit the ceremony of tipping. 'Mr Traffick brought her down on Windover Hill, Sir Thomas, and she'll never be worth a feed of oats again. I didn't think a man was born who could throw that mare off her feet, Sir Thomas'. Now Mr Traffick, when he borrowed the phaeton and pair of horses that morning to go into Hastings, and had dispensed with the services of a coachman, and had insisted on driving himself' (pp. 232-233 and facing illustration).

When I read this passage I remember a letter by Jane Austen (non-fictional) where she frets over an invitation to visit someone as she hasn't got the money to give tips. I remember a letter by Samuel Richardson (the 18th century novelist, also a non-fictional one) where he dreads going to a house because he is awkward at this "ceremony" of giving tips. Not only must it be done, must the person have the money, they must not be gauche in the giving out of these things. They must do it with a panache.

Mr Traffic is lacking here.

He is also cheap -- at least we are to infer this. He has been given an enormous sum with Augusta and will not spend any of it, not even to secure to himself an experienced coachman to drive the carriage. The result is an innocent bystander: the horse, is destroyed. This is not the only novel where Trollope uses someone's attitude towards and treatment of horses to characterise them. When we first meet Burgo Fitzgerald in Can You Forgive Her?, he is busy destroying a horse by riding it furiously, carelessly, wantonly. This is what he would have done to Lady Glen had he married her is the implication.

I wish Trollope did not condemn Mr Traffic also for his lack of upper class fittedness. That is, the implication here is a real gentleman would not have driven in such a way as to let the horse trip. Says Sir Thomas looking at the poor animal:

"'Of course I ought to have known that he couldn't drive'.'A horse may fall down with anybody' said Mr Traffic'" (p. 235).

We are not to believe that one. One can of course -- as a reader who does not identify with this class of people at all -- turn the tables on Sir Thomas, and say his assumed snobbery does not make a Merle Park into a Stalham. It takes true caste confidence for that.

Geary's picture shows us two very large male figures. Neither is handsome. This is important. Both are aging. We see the coachman from the side; he has a sallow lined face, long nose, awkward mustache. His hair is longish, cut roughly with a scissors (he probably cuts it himself); there is a lightly indicated growing bald spot at the top of his head. This coachman's hair is thining. He is dressed in a slightly aging livery (perhaps the first outfit?), but one which was originally very expensive. He holds one of his hands towards Sir Thomas in a gesture of dismay and explanation. The hand seems to be depicting some scene The other holds the top hat. Sir Thomas's face is very fat, bewhiskered, grim. He has a large bulbous nose. He is bald across the top of his head. He has a fine top jacket; it doesn't close over his great expanse. We see a lovely bow tie-ribbon held down by an expensive pin around his neck. A waistcoat with a watch hanging across it. Behind them are a window and large wide door. We see a coach through the doorway; in the distance are further large buildings. The room itself is furnished in the same crowded way as the Dosett residence. Curtains on the window -- light this time. Little round miniature pictures line the threshold of the door. We see a gaslamp on the window; some objects on the floor look like they have something to do with the coachman's occupations. The trees in the very far distance through the window are picturesque, the lines running hither and thither. Serpentine lines do not dominate this picture or that of the outside of the Dosett residence in the way they did the Dormer residence and the park scene; instead the lines go up and down. Rigidity, sternness is suggested in the scene between the coachman and Sir Thomas. They are men who are practical. They would not trip a mare. Their faces look concerned.

Doubtless an "angel of light" would not trip a mare. Why does Augusta betray her sister? She's got her man; why should Gertrude not have hers? Why, forsooth, Mr Traffic is not the dream man Gertrude and Ayala want. He is scorned and despised by them. She knows she has taken something second rate, and the definition here is not second rate in terms of depth of understanding, kindness, loyalty, decency, tact; that he lacks sensitivity and is willing to bully (as he did Augusta over Ayala) to get his way; not that he lacks all those wonderful qualities we see in Colonel Stubbs and doesn't have the ignoble ones. No it's that he doesn't pay his way (but then neither does Frank, so maybe that's not so important to Augusta); he can't manage a carriage, probably would not be good at hunting, lacks sexual allure.

For my part I would feel a wee bit sorry for Mr Traffic facing Sir Thomas in the street were it not that I feel much sorrier for the horse. Now the mare is going to be shot. I find myself remembering Swift's tales of the houynhymns and yahoos.

Cheers to all, Ellen Moody

(PS: I just realised what the name of this large board of lists refers to. Could they mean to celebrate themselves as yahoos? Did the person who decided on the name read Swift's book? Surely not.)

To Trollope-l

February 18, 2001

Re: Ayala's Angel, Chs 25-30, Pictures: A Fatally Crippled Horse (II)

On my PS and the name of this vast website, my husband says, oh no, not to think of Swift's yahoos and houynhyms; the name "yahoo" refers to a shout of glee when you find something; the synonym would be "Eureka!" It has an exclamation point after it in the ads. He says "Yahoo!" started out as a search engine. They are not glad to be yahoos.

This does have to do with hunting: horses have long been regarded as noble beasts, though they were not always well treated by people who used them daily in their working lives. The appeal of hunting, its pastoral and idyllic qualities, its sheer pictorial elegance, and its association with aristocratic ways of life is partly dependent on the rider's relationship with his horse. Remember how Ayala has to have the right outfit to get aboard her horse. She has to look right, meaning aristocratic. The yahoo has to come up to the houynhym.

Ellen Moody

Re: Ayala's Angel, Chs 31-36, A Picture of Tom Tringle

How fortunate that this week's instalment has just one illustration and it is of Tom Tringle. It allows me to contribute further to this thread we have had this week on Tom.

The caption is "After that they went out and ate their dinner at Bolivia's". It is a visualisation of Tom and Faddle at dinner just after Tom has written his letter to Colonel Stubbs:

"When after making various copies, Tom at last read the letter as finally prepared, he was much pleased with it, doubting whether the Colonel himself could have written it better, had the task been confided to his hands. When Faddle came, he read it to him with much pride, and then committed it to his custody .After that they went out and ate their dinner at Bolivia's with much satisfaction, but still with a bearing of deep melancholy, as was proper on such an occasion" (Folio Society Ayala's Angel, introd. AEThomas, Ch 35, p. 284).

I dislike it -- as I do another of the visualisations of Tom in this novel. In the first visualisation of Tom chasing Ayala down in the Coloseum, he was drawn as a clumsy, plump-faced rich young man whose eager open expression showed his vulnerability. While there was no savoir faire, there was no caricature, and the figure was instinct with energy and life. This picture and one of the two later ones present Tom as an energy-less sap. We see a comic caricature of a fat young man slumped over his glass of wine; his face is leaning on a hand which is held up by an arched arm whose elbow leans heavily on the table. He looks comically glum. On the other side of the table is Faddle, here a thinnish, rough faced young man in a not very well fitting suit, worn shoes, badly cut hair, and air of hauteur about his face as he looks on his menu. At a distance are waiters, other tables, at one of which we see a lady and gentleman. By the side of our two young men are their top hats and cloaks hanging from a stand; in the distance an older waiter is watching them. The whole thing is insufferably condescending on the part of the illustrator (Folio Society Ayala's Angel, introd. AEThomas, illustration facing p. 288). It reinforces Trollope's fleeting moments of snobbishness towards Faddle; it dismisses Tom as a blob. What Geary has done is emphasise the "as was proper on such an occasion", the anaestheticizing distancing irony and encouraged us to dismiss what is real in the young man, something that Stubbs strongly respects.

When I quoted my daughter, I didn't mean to say I thought her opinion of Tom at all accurate, though next week's instalment (which I read tonight) has Mr Dosett echoing her: "Tom is an ass", to which Mrs Dosett gives some relief to the reader who has felt for Tom with the repartee, "I suppose Colonel Stubbs is an ass too" (Ch 39, p. 317). I did think she would express spontaneously something of what Trollope was dramatizing in Ayala's response to Tom.

I turned to my daughter because in this section of the book Trollope means us as yet not to feel too deeply for Tom, though as the novel progresses Tom becomes a figure whose emotional dimensions break through the artificial design of the book and occasionally overtopple it. Imogene is a mere threat. We are as yet to look on him as the world does: an incompetent, someone who is ridiculous because he can't control his feelings for others who are (as people usually are) pretty well indifferent to everyone but themselves except as others fit into their self-validation and needs. This is not Trollope's attitude towards this young hero. The comedy is painful because among the peacock struttings is the sense of someone dislocated through not fault of his own. Tom is another of Trollope's social outcasts whose ridiculousness to others -- not, note to Stubbs -- comes from his having dreamed of something better than the diurnal and banal, though he lacks the ability to put his dreams into anything beyond a mercentile society's high priced objects. There is something frantic about Tom, something unbalanced, but the crazy pigheadedness of his behavior came from an exhilaration of his spirit -- akin in its way to Ayala's dreams. Tom is another variant on the Rev Josiah Crowley figure, and the irony is his wealth which protects him also disables him. Would he not be better off if he had to take a position as a postal surveyor in Ireland? Then he'd get away from all those who despise and don't know what to do about him. The question is not how we feel about Tom, but how Trollope does. Instead of dull eyes, the illustrator should have given the character overbright ones.

It is refreshing to find that at this point in Trollope's career he is eschewing the duel. Stubbs calls it absurd, and says he would never consider it. This is a far cry from what we saw in Dr Thorne. Stubbs simply rebuts as stupid and irrelevant to the case at hand the resort to violence and ego trips, the enjoyment of bullying, the violation and threats to other males based on male macho behavior as a way of forcing other men to behave what is called "honorably" to their female relatives that we saw in characters like Frank Gresham and Lord Chiltern. We should note that Tom echoes this when Frank Houston jilts his sister. Still one cannot deny that Tom's behavior is counter-productive, useless, unhealthy for himself because so demeaning in front of others. The point of propriety has ever been self-protection from the instinctive derision of the strong. Tom Tringle has hitched his wagon to Faddle's because Faddle is also weak against the world, also a misfit -- though for different reasons.

So I would maintain that what Trollope is showing us here is not simply to be read and dismissed as a passing phase in a sensitive naive male. Tom will not grow out of this. After the book is over we are to hope he may learn to cover up his vulnerability with a carapace -- and of course those millions continually raked in at Lombard Street will help. But in essentials he will not change. And I'm not sure that Trolllope doesn't think this is all to the good. The book does not admire the Batsbys; it is written on behalf of the imagination. Houston redeems himself when he reveals he can act on behalf of some inner feelings. Would that we had more people in the world who take seriously and look upon as important their sense of a need for others, their respect for the integrity and value of others (in this case Imogene's), in the brave acting out of dreams and romance? And these things Stubbs clings to also. I am with Mrs Dosett in not seeing anything in Ayala worth these two men, but, as they say, Cupid is blind, or to put it in modern terms, sexual instincts go for the challenge, for the piquant, for a child-woman who is herself a dreamer and cheerfully upbeat by instinct. Perhaps the latter is somewhat irrationally the most important of Ayala's attractive qualities. Ultimately Stubbs and much more Tom Tringle are melancholy figures.

As the book moves on, Tom takes on roles that make readers uncomfortable. Alice Ellis Thomas writes that his behavior is the kind which does not find "general approval today. Today Tom would be advise to seek psychatric help". I don't know why she has the qualifier "today". I would counter that Tom is the best sort of blocking character. Other interesting blocking characters are Imogene Docimer, Mr and Mrs Dosett, Lucy and Hamel. Each in their different ways is true to some integrity or self-sustaining decision on how to live which does not vacillate in accordance with momentary pressures. Imogene does say in a letter next week that she was partly to blame for listening to her brother for a while. By their refusals to yield to the moment, they show up what is perverse in the demands of world, whether because we see them so deprived or so passive ("mute persistence" is the word Lady Emmeline uses for what she can't bear about Lucy), or because they genuinely actively seek what they want. Ayala is a kind of child-like parody of this, half-hysterical as she holds onto the bedpost in her bedroom. In tomorrow's chapters Mrs Dosett has the best line in the book in one of its best scenes, the one in which Lady Emmeline is shamlessly egregiously hypocritically trying to rid herself of Lucy:

"Do not you feel that the girls should not be chucked about like balls from a battledore?" (Ch 40, p. 323).

There were some moving phrases and remarkable letters in this past week's chapters, as when our narrator says if Faddle's disappearance from Tom's life: "Our friend Tom saw nothing more of his faithful friend till years had rolled over both their heads" (Ch 36, p. 291) I found the interchange of letters between Hamel and Lucy and the confrontation of Sir Thomas and Hamel relevant to our lives today. Neither man was in the wrong. The sociological detail of Hamel descending into the underground afterwards was perfect (p. 269). Tom's stalwart inability to compromise fit in.

This is not to say I would refuse to fit in the way Tom does, that I can at all understand how he can be so absurd as to think such a trinket could make a girl love him. The view of females Tom and later Captain Batsby have is they are frivolous mindless, and vain, all superfice. But when I am embarrassed for him it's out of a sense that he hasn't caught on, doesn't get the hypocrisies right. That I empathize with.

What a gallery of unconventional portraits of males we have been getting in these relatively unavailable Trollope books.

Cheers to all,

Ellen Moody

Re: Ayala's Angel, A Picture of Pretty People

Reply-To: trollope-l@yahoogroups.com

March 5, 2001

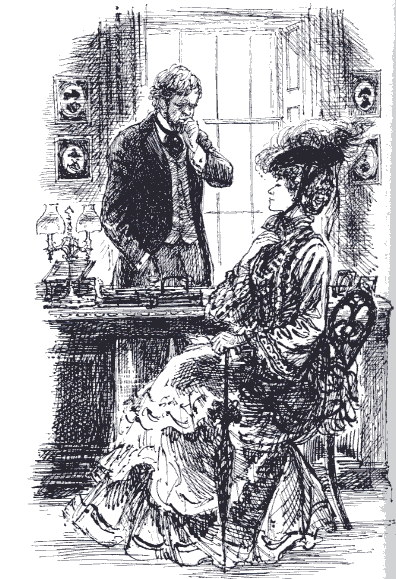

This past week's instalment has but one illustration. Geary visualises the scene between Reginald Dosett and his sister, Emmeline, Lady Tringle (née Dosett). I write Lady Tringle's name this way to bring out their relationship as sister and brother; we could say the novel is a Dosett story; as it opens it is framed that way. As with Mansfield Park where we hear the story of the marriages of the three Ward sisters, so here we are told how each of the Dosetts ended up in the position in the world they now occupy -- with the qualification that Adelaide Dosett and her husband, Egbert Dormer is now dead.

What is most striking about the illustration is how handsome is Reginald, how pretty Emmeline. Both are blonde, tall, elegant, genteel. The caption is formed from Reginald's careful response to his sister's request that they again switch the sisters: "'We will think about it', he replied gravely. The passage pictured is as follows:

At Somerset House Lady Tringle made her suggestion to her brother with an even more flowery assurance of general happiness than she had used in endeavouring to persuade his wife. Ayala would, of course, be married to Tom in the course of the next six months, and duriing the same period Lucy, no doubt, would be married to that very enterprising but somewhat obstinate young man, Mr Hamel. Thus there would be an end to all the Dormer troubles', and you, Reginald, will be relieved from a burden which never ought to have rested on your soldiers.We will think of it' he said very gravely, over and over again. Beyond that "we will think of it", he could not be induced to utter another "word" (Folio Society Ayala's Angel, introd. AEThomas, pp. 325- 326 and illustration facing p. 325)

Here is the illustration:

We see a sumptuously dressed youngish woman who has her hand to her bow under her chin which helps keep her hat in place. She has an air of superciliousness in the way she holds her body. Her eyes are half-closed; she looks smug. We can see she has not had a vulnerable or hungry moment for years (the hat is a marvelous creation. She is all frills and furbelows. Behind the desk Reginald has his hand to his mouth as he thinks guardedly. His desk is solid; his suit is just beautiful: fancy bow, studs in his cuffs, waistcoat; he is well-groomed. He and Mrs Dosett may not get much to eat, and she may spend her life sewing, but it is so that he shall look like this. What is most striking is how handsome a pair they are: he is blonde and tall with an attractive face, though rounding over the years. I can see her face on some mannikin; if she could smile, she would be an alluring graceful model in some ladies magazine. She too is blonde and tall.

This illustration has me returning to the opening of the book lost sight of in all these romances. I find we are not told when Adelaide Dosett died or from what disease, only that she had predeceased her husband. We are told that Adelaide may have lacked Lady Tringle's "perfection of feature" and "unequalled symmetry", but had been the "more attractive from expression and brilliancy", and had had many offers of marriage from men far richer, more powerful, more socially connected and influential than Edgar Dormer:

"To her Lord Sizes had offered his hand and coronet, promising to abandon for her sake all the huants of his matured life. To her Mr Tringle had knelt before he had taken the elder sister. For her Mr Progrum, the popular preacher of the day, for a time so totally lost himself that he was nearly minded to go over to Rome. She was said to have had offers form a widowed Lord Chancellor and from a Russian Prince. Her triumphs would have quite obliterated that of her sister had she not insisted on marrying Egbert Dormer (Ch 1, p. 2).

This recalls the opening of Mansfield Park which has been adduced for comparisons already. The two books assume an attitude of mind which looks at two sisters from the horizon of what matches they were offered -- defined as their destiny -- on what beauty purchases is not. However, the difference in scope and in tone are great: Austen is all acid. Trollope is both fuller about the men, kinder to them, and more amused; his sweep is larger in scope, across the world. He seems to take more into account an inner self which allured, and Adelaide's attractive expression and brilliancy suggests where Ayala has inherited her power of dreaming. He is both fuller about the men, kinder to them, and more amused; his sweep is larger in scope across the world. At the same time both openings declare themselves as belonging to the genre of romance. If you go back to Sir Philip Sidney's Arcadia you will find a description of the two heroines (Pamela, Philoclea) which talks in a similar antithetical generalising way which smooths everything into a sing-song of socially acceptable sweet qualities. Whenever and wherever you see this sort of thing, you know that some aspect of critical consciousness has shut itself down.

We are also told in these opening pages that Reginald Dosett was beautiful. But as in the opener of Mansfield Park where Austen tells us "But there certainly are not so many men of large fortune in the world as there are pretty women to deserve them", so Trollope that "Alas, to a beautiful son it is not often that beauty can be a fortune as to a daughter". Have others noticed that Reginald is described as beautiful? I looked and discovered little phrases suggesting Mrs Dosett is plain, square and Mr Dosett attractive, but not until I looked at this week's illustration did I get another irony of this story: women may "rise" in the world through their physical qualities, the genetic appearances of their sexuality; according to Mr Trollope, not so men. Something else is what gets you ahead.

When we read Is He Popenjoy? I kept going back to the opening where there was a sordid fable about sexual jealousy, money, and revenge, which Trollope said his novel was an analogy of in middle class terms. I suggest all novels are framed at their opening, and careful attention to it tells us what terms we are to read them in. This is romance, high romance (as is Sidney's Arcadia), but with certain twists which reflect Trollope's obsession and interests and the expectations of his audience. As we have been noticing in both our books, Trollope's portraits of males, of male options, of ironies about male sexuality is at least as interesting as his portraits of females, their options, and the ironies that swirl around what is done to their sexualities. Perhaps beautiful men are worse off because the female is (or was at the time) supposed to be passive, and thus no rich woman could so plainly run after young Reginald Dosett for his looks the way rich men ran after Adelaide and Emmeline.

Rereading this opener I also discovered that it was said that Adelaide Dormer's death killed her husband: "He had dropped his palette, refused to finish the ordered portrait of a princess, and had simply turned himself round and died" (p. 3). Again, we are told of this death through a sentence and with images structured in such an echoing symmetrical way that we are kept at a distance from reality. This is a death taken not quite seriously. The death of Egbert Dormer is a pretty picture which laughs at the absurdity of what the artist is called upon to do to make money. It is a linguistically polished moment, like some heroic couplet by Pope.

This posting is partly written in response to RJ's last couple meditated postings. He fixed this novel in a type of book and as coming from a milieu which saw individuals as part of networks of wealthy or at least genteel families. Prompted to return to the beginning of the book by this illustration I find this is so. He is probably right to say that many people would read this sort of book morally partly based on an ethical response to the kind of choices such people make to stay in their group; I'm not sure that in this particular case Trollope meant the book that way. He seems to have departed altogether too often from the economic (or if RJ prefers household money) level of life: we are in this coming week's chapters in a dream world where poverty is not an issue and all act freely.

My quarrel, or perhaps I should say demurr at moralising readings comes from the reality of what these turn out to be. It's not just the narrowly judgemental pronouncement aimed at this or that character. Often what is said is nothing more than apportioning of blame: it rarely goes beyond this to some larger perspective which is not moral but largely description of life or philosophical. The idea seems to be by judging these characters we find some lesson for ourselves. I do it too. I did it last week about Frank Houston. It comes natural. However, if we are to think seriously about why bother reading such a book, and what use is it, we might think how this sort of thing just reinforces a group's norms and is not moral at all.

More generally behind this sort of talk lies an attempt to validate our choices. Ah, I didn't do that and so even if I am miserable now, I don't have to despise myself and didn't know these troubles -- in this novel those of the Dormers and Tringles. Or ah, I did that, and know just what this character is feeling. It helps me to feel with him or her, releases the pent-up emotions that find no release elsewhere. In this novel I suggest the case used most this way is that of the Dosetts. Nothing wrong here -- as long as you recognize what you are doing. Then the novel becomes a mirror by which you can look into your heart.

What I object to is the assumption that usually comes out when people don't admit that they are simply seeing or validating themselves and turn the parable into an exhortation. If only you will behave in some exemplary manner, this won't happen to you. All will be well. Reading can become a way of distancing ourselves from what goes on within us; a way of reinforcing tyrannies from the outside and society's censureship onto ourselves. We may not feel this as we read -- indeed most people do not. But if we articulate it in the way RJ proposes, put the words in such moralising frameworks, does not the experience we have had from the books turn useless. The experience of reading becomes just one more reiteration of what we come across in society and comes into our heads from the real world. The self then fails to put any barrier between him or herself and the world as it enters the book. To turn back to those private letters of Dickens, what's profound there is the man's sudden freedom to articulate what he is really thinking and feeling which has nothing to do with the world's or his milieu's morality. Indeed that is not irrelevant; it is what punishes, what deprives.

Cheers to all,

Ellen Moody

Re: Ayala's Angel: Chs 43-49: Pictures, A New Attitude Towards Duelling?

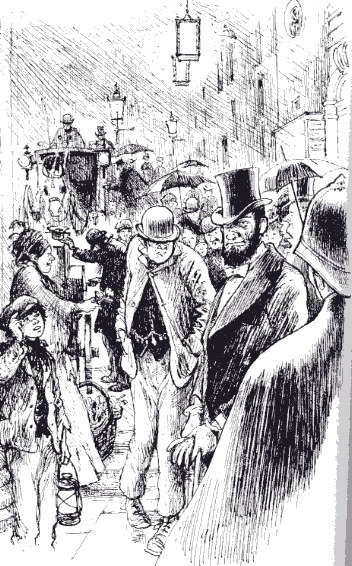

The first of this week's two illustrations have an interest beyond the individual novel. It is a picture of Colonel Stubbs standing outside the opera house as yet unaware that nearby is a glowering Tom Tringle ready to jump him:

The caption is: "He was one of those who by their outward appearance always extort respect from those around them" and the scene depicted is just that moment before this sentence when Stubbs has shut the door on the ladies and a policema is standing by. The lines run:

Then the door of the carriage was shut, and the Colonel and the Colonel was left to look for a cab. He had on an overcoat and an opera hat, but otherwise was dressed for dinner. On one side a link-boy was offering him assistance, and on another a policeman tendering him some service (Folio Society Ayala's Angel, Ch 44, p. 357 and facing illustration).

As with a number of illustrations of this novel the scene depicted attempts a realistic social visualization. Geary has been careful to make Stubbs conventionally ugly -- he has a stubby nose. Yes, it is round, flat, and anything but aquiline. Perhaps this is one explanation for the name? His lips are a long straight line; his eyes are sloe-like; a shabby thick beard, prickly is on his chin. However, out of his eye we see a pacific, sensible expression, and he is clearly a gentleman, self-possessed. Just behind him and slightly to the left we see Tom. Oh dear. Tom really looks genuinely loutish by which I mean crude, sloppy-looking and stupidly belligerently aggressive. He is soaked from the rain (it is raining); his coat is slightly too tight and buttoned by one button at the top. While our Colonel has a top hat which sits leisuresly over his head, Tom's is round and squashed down. Tom's hands are in his pockets, and his face is even "uglier" than the Colonel, the nose yet stubbier. Tom's legs are turned towards one another, very awkward looking.

But beyond them we see to the right of Tom a poor woman. She looks out with squeezed eyes, holding a flower. She is trying to sell it. She holds tight around her body a wrapper; she has a soaken miserable excuse for a hat. Near her a young boy holds his hat and a lantern. He is the link-boy. Near the viewer is the outline of part of the policement. Further off we see a crowd: one carriage is distinguishable, but there are so many faces, so many umbrellas, such a suggestion of buildings, with repeating figures of men which echo one another at a distance, we really get a feeling of a city's anonymity.

What is of interest here beyond the individual novel: Trollope presents duelling as absurd, loutish, something only fools do. In the particular instance it is Stubbs who fends off the unexpected sudden assault and attempts to soothe the policeman into not doing his duty; however, later in the book Tom himself laughs at Gertrude for demanding he require a duel of Frank Houston.

What has happened? We all remember how in Dr Thorne we are asked to applaud Frank Gresham for cornering the man who jilted his sister and attempting to beat him up, to hurt the man. There we were asked to laugh at the man who didn't come up to stuff. Dr Thorne is not the only book where Trollope defends duelling as manly, reasonable, the right way for someone to enforce social codes.

The interest of this scene is the right it gives us to ask, How far does Trollope reflect changes in his society? This does not just have to do with duelling, but with his anti-semitism which I have always thought was an unscrupulous use of commonplace ugly prejudices, unforgivable in our time where concentration camps emerged, but undestandable in a time when this result of reinforcing savage tribalisms could not have been foreseen.

Or is it that something has happened in Trollope's own life which has made him change his mind? This is an interesting question. One would have to study the man's life closely, look into commonplace occurrences in London and England during the period. If you could prove that he did have some genuine inner change, then you could argue that his anti-semitism -- and it is real in several of his novels -- was not just an unthinking reflection of his times. If you were led to come to the conclusion, that, to coin a phrase from Samuel Johnson's description of John Dryden, as Dryden changed, so changed the nation, it's not that one could excuse Trollope from reinforcing ugly prejudices, but one could at least suggest he himself did not necessarily participate in them.

The issue of duelling too is not insignificant. In our own time no one suggests that these sorts of solutions to social hurts, betrayals, shaming and humiliation which yet do not reach the level of a "crime" ought to be punished or prevented in this manner. But male macho ideals of violence and aggressive as a criteria for respecting a male are by no means gone. Trollope appears to have changed his mind or his public stance. Peter Gay calls this aspect of Victorian culture "The Cultivation of Hatred". So we may say of Trollope's hero -- and it is a perverse point of view which names Sir Thomas as the hero -- that not only does he explode the false dreams of the animus, is himself a cynosure against superficial materialism (think of his cottage), but he is also someone who defies a macho culture of aggressive belligerency as the measure of man. I wish Geary had pictured the scene in the railway carriage as it was witty, but this is the more important moment.

Cheers to all,

Ellen Moody

Re: Ayala's Angel: Chs 43-49: Pictures, Another Quiet Landscape

This week's second illustration is yet another of the book's many quiet picturesque landscapes:

The caption is "She arrived safely on the following day at Merle Park." There is no other verbal text (Folio Society Ayala's Angel, Ch 49, p. 394 and illustration facing p. 393)

What Geary has done is again reverted to the 18th century Gainsborough-picturesque lightly sketched in that he has availed himself of throughout the novel. Again we see no individual. From the back a carriage is quiet driving towards a solid mansion. To the right we see much autumnal foliage; a tree forms a kind of framing device. To the left we see bushes, more trees fanning out to the distance. In the front is a square well-built house. The drawing is made up of many lines.

The illustration may serve to remind us of how one of the central themes of this book is the perverse ways in which sexuality and rebellion (the Oedipus and Electra complexes) emerge in this novel, how accurate Trollope is -- though it may make us uncomfortable to remember back to what we were. The book is not superficial when it comes to sex -- Trollope rarely is. We have not much discussed Gertrude and Captain Batsby. To me the pair of them are distasteful, but then I suppose they would fit in P. J. Wodehouse novel, except that there is an earthliness about Sir Thomas, a desperation about Gertrude and the sense of a need for safety that gives this theme needed depth.

More: it is one in a series which asks us to dream over this novel as a romance of London life in the late 1870s as one might like to see it from afar.

Cheers to all,

Ellen Moody

Re: Ayala's Angel, Chs 50-54: A Picture: Tom in Retreat

This past week's instalment has again but one picture. It is another of Tom. Four out of the sixteen illustrations feature Tom; three more are of characters acting on or reacting to & against Tom's desires. This bringing out of a subplot or story by pictures is common in the original illustrations to Trollope's novels: if you didn't read the words of Orley Farm, you would think it was the story of a young gentlemen deprived of his inheritance and in conflict with his mother much more than the story of a woman accused of forgery. In the case of Orley Farm I wondered if to the original 19th century reader, the story of Lucius was much more important than it seems to the reader today -- especially the injustice of his position. In the case of Ayala, many a modern critical comment or whole essay suggests that the character who most interests us is Tom Tringle.

I don't care for the picture as the facial expression of the fat-faced young man burrowing in his bed is a caricature: a ludicrously down-turned mouth, eyebrows that are diagonal lines over his nose making an upside down triangle, one hand clutching his forehead, with the other coming close to his face; his arms covered in a frilly white shirt with long sleeves invite the reader not to take Tom's anguish seriously. But Trollope does so take it; so do all the characters, even towards the end, Ayala; and this illustration could be moved about to face several passages in the novel where we are told Tom has retreated to his bed, something people who feel overwhelmed, depressed, and anomie do.

In the particular instance, the caption is made up of Sir Thomas's abrupt demand: "'You start on the nineteenth', said Sir Thomas", and the passage opposite the picture runs: