[For Trollope's Christmas story, "The Telegraph Girl," which takes off from the conditions of employment described below, click here].

Eight hundred young women at work, all in one room, all looking comfortable, most of them looking pretty, earning fair wage's at easv work, -- work fit for women to do, work at which they can sit and rest and not be weary, with a kitchen at hand and a hot dinner in the middle of the day, with leave of absence without stoppage of pay [p. 28] every year with a doctor for sickness, and a pension for old age and incompetence, -- for the young women as years roll on will become old, -- with only eight hours of work, never before eight in the morning, and never after eight at night, with female superintendents, and the chance of rising to be a superintendent open to each girl! Is not that the kind of institution that philanthropic friends of the weaker sex have been looking for and desiring for years? What would Hood have thought of such an institution when he sang his"Song of the Shirt"2, -- what those beneficent friends of distressed incompetent governesses who are using all their efforts so nobly to provide bread for poor females in distant lands? And all this in a government office, under government surveillance, which, in this country is of all surveillance the most tender, -- though there be and ever will be grumblers. That such surveillance is will I think, be admitted when I have described the position of these eight hundred females. And all this has sprung into existence during the last eight years! By those who have watched the efforts made for female employment in other branches of business, at printing, for instance, and watch-making, sometimes with but moderate effects, sometimes with heartrending failure, will not this be welcomed as a great success?

The Civil Service of the country has been a rock of safety to very many men, a haven of refuge when no other haven could be reached. And it is so still, in spite of that great barrier at the mouth of the harbour which we call competitive examination. There is a security in it, an absence of cruelty, a justice, a clemency leaning a little too much, perhaps, to the side of faulty servants, a philanthropy and consideration forced upon it, both by its magnitude and its publicity, which no other employment can enjoy to the same extent. If we put aside the question of direct remuneration -- the amount of salary paid -- and look to the other circumstances of a clerk's position, we shall find that the man employed by the Crown has shorter hours of labour and longer hours of absence than he who is in private service, that he has an infinitely stronger right to his position, that he is less likely to be dismissed from personal dislike, less liable to arbitrary punishment, more gently considered in illness, and very much more generously treated in regard to pension. Eight years ago all these good things were enjoyed only by the stronger sex. Luckily the stronger sex is prone to take a wife to itself in prosperous circumstances, and in this way the benefits became common to men and women. But the stronger sex does not always take a wife -- does not do so quite so often as it ought -- sometimes cannot afford to do so till middle life. And therefore women have not had quite their share of government nourishment. But when we see eight hundred women at work in one room -- eight hundred female government clerks -- we feel that something has been done for them.

Everybody knows the General Post-Office in St. Martin's-le-Grand, near St. Paul's. Everybody knows that there are now two great post-offices at the same place, facing each other, the elder one having been found altogether insufficient for the purposes required, though when it was first opened, about forty-five years ago, it was supposed to be absurdly too large for any possible requirements which the country could have for such a building. Those who pass from Cheapside into Newgate Street after the lamps have been lighted may observe, on looking up, that the whole top floor of this new bulding is illuminated. It is here that the eight hundred young women are at work, and their business consists in the receipt and dispatch of telegraph messages.

The work, on which they are all engaged is performed in one large room, -- a room that appears to be low because of its great size but which is in truth of considerable altitude, and is lighted by roof-windows. I wish I could say that it is well-ventilated; -- but that difficulty of giving a sufficiency of fresh air without too much of it to a large body of men or women working together has not as yet been solved at the Telegraph Office. Open the windows, is the easy solution to which the unpractised ventilating theorist would come; yes, or take off the roof, and you certainly would get plenty of fresh air. But these eight hundred human beings -- here there are many more than eight hundred -- are tender subjects, who as to their own immediate perceptions, are much more affected by cold than by unwholesome air. The difficulty in ventilation consists very much in this, -- that the person to be ventilated does not know that he wants ventilation. You shall find five travellers in a railway carriage -- you, joining them suddenly as an unhappy sixth -- who do not know that they are being smothered. Tell them so, and they will bitterly resent your interference. Remain with them for an hour, and you shall not know you are being [p. 28] smothered yourself. These eight hundred lady friends of mine require some process of ventilation of which they themselves shall be kept in ignorance. It is to be hoped that some such process may soon be found.

This great room is divided, something like a church, into transepts and naves; such , at least, is the first idea, theough the form of it when studied does, in fact, assume the shape of a great letter H. It contains an area of very nearly two thousand feet, and those who are curious in statistics may be glad to know that the length of the instrument desks amounts to two thousand four hundred feet. Though it is all one room, it has its well-marked divisions, its east end and its west end; and thus the Indian telegrams and the foreign telegrams are no more mixed up with the Liverpool and Glasgow business, or those with the internal metropolitan telegrams, than is Grosvenor Square with the Victoria Docks, or Regent's Park with Kensington Oval. It is a "mighty maze," and certainly appears so to the stranger when he first finds himself among all these young women but he soon finds that it is "not without a plan."

The stranger, if he be at all such a stranger as I was, will think a great deal more about the young women than the telegraphy. To those who are the masters in the place, who have used their skill and science in concentrating so much that is useful in one place, and who are thoroughly aware of the importance of the interests which are confided to their charge, the security and expedition and cheapness of the messages are, of course, the points of attraction. To me it was the conditions of the girls -- their appearance, their welfare, their respectability, their immediate comfort, their future prospects, their coming husbands, their capabilities, their utility, and their appropriateness in that place -- or inappropriateness. The reader may, therefore, know at once that he will learn nothing from me about telegraphy; whether he will learn anything about the telegraph girls I will not say, but it is my ambition to tell him something. Even those prolonged iron spouts down which came and up which went the metropolitan messages, which are not communicated by wires but which are dispatched bodily by atmospheric pressure within two miles of the building at the rate of about thirty miles an hour, did not interest me much, because they are waited upon by boys and not by young women.

My first point of interest in the matter was to know how the girls got there. Though there be at present eight hundred of them -- the actual total in the principal office is eight hundred and forty-three -- even though there were eight thousand there would certainly be great competition for the service. And then of those who would want to be employed so many would be unfit! And then again, that question of character -- what we may call respectability -- is one much more difficult among women than men, but one which so imperatively demands to be asked and answered. A young man of bad character will do harm to his associates -- very great harm; but he will not be held to be so fatally noxious as a young woman of bad character among those who are pure. Mothers and fathers, if they will think of their own children, will feel that it is so. They are anxious no doubt to keep their sons from evil contact; but for their girls --! I felt at once that it was a very delicate matter -- this of selecting these young women for the public service.

And then what did the girls do when they were there? Of course they would send messages and receive them -- more or less expeditiously, according to the adroitness of their fingers, eyes, ears, and intellects. But it is not only the work which is done by any great mass of persons working together which is interesting, but all that which must necessarily be done beyond the work. For mere production, a well-arranged machine is more interesting perhaps than a human being. They who look only to what labourers can be made to produce are too apttro regard these living souls as though they were wound up by some key or windlass, or set in motion by the power of heat, and that they would so do a certain fixed task, and that then there would be an end of them. To me, when I have seen a half-naked, brawny puddler turning the iron, or a miner digging out the gold-containing rock, or the ploughman in his tucked-up frock striving to drive his furrows straight and deep, I have felt more interest in the man's willingness to serve, or in his mutiny, in his conversation, if I could hear what he was talking , or even in his silence, in the expenditure of his wages, in his bread-and-cheese and beer, in his hilarity or sadness as he sits during his allotted minutes of idleness with his pipe in his mouth, than I have in the profit or loss accruing from his work. And so with these girls. There were the messages to send and receive -- of course. But what else was there done in that large room? Did they talk? Oh! -- if I could only know what those two pretty girls in the distance were talking about! -- not from curiosity, but that I might judge somewhat of their inward natures, [p. 29] -- whether they were good or bad, happy, pure or impure. They looked to be good and happy, and pure; and I thought to mysef that I should like to take them to the Zoological Gardens, and to make them feed the bears and ride upon the elephant, and then to hear what they would have to say about Madame Tussaud's horrors, and after that to give them their dinners and send them home happy. As I was thinking of all this, the newest system of telegraphy by sound was being clearly and skilfilly explained to me; -- but I did not pay by any means as much attention as I ought to have done to the new system, so much was my attention taken up with those two pretty girls -- with others.

And what was their conduct generally? I found it difficult to frame my questions so as not to betray any improper curiosity. But I was very anxious to know whether they -- flirted, for there are young men in the same room. I thought that had I been a young man there I might have been tempted. As far as I could judge by looking round, there did not seem to be anything of the kind. And then in other respects, how did they behave themselves? Were they punctual, attentive and obedient? Was it often necessary to punish them, and if so, in what manner? Were there frequent dismissals?

And then what did they get -- what in immediate money, what in prospects, what in comforts, what in privileges, what in respectability? They were all then, of course congregated in that one room, and busy in accommodating the instant haste of a hurrying world, only for the sake of what they could get. Was it enough to make them happy and comfortable; enough to give them plenty to eat, and decent rooms to live in? I could see that they were all nicely dressed; but when a large number of girls have come together, each will spend her last sixpence in dress rather than be less well accoutred than her neighbours.

And who did they live at home? As to that I knew that I could learn very little. With their parents, generally, I hoped. But there must have been many there whose parents were at a distance -- many orphans -- many so far alone in the world as to have to look out for ther own lives as most young men are called upon to do. These would come and go to and from their offices indpendently as do the clerks in the Treasury or War Office. What sort of life do they make of it?

As I had imagined, I found the competition for the situation to be very great. Who does not know how many girls there are, somewhat above the rank of domestic service, who have been taught their three Rs with more or less success, and to whom there comes early in life the necessity of either earning their bread or else of eating very little bread? Indeed, for what service, especially for what government service, is there not competition? Great efforts have been made to do away with the horrors of competitive patronage, that is with the giving away of situations by favouritism. Therse horrors need to be more more horrid because the favouritism displayed was not generally that of open friendship but of political adherence. Active manipulators of votes in small boroughs, or even in large cities, would think themselves entitled to a portion of these favours, and the distributors of patronage would find themselves unable to resist the claims made upon them. This was bad on all sides, but to none was it so bad as to those who were obliged to distribute the prizes. Had they nothing to give, they would be asked for nothing. But while the bestowal of these gifts was a necessity to them, there was no resisting the political cormorants who had supported them or who would hereafter support them in their political combats. It was this feeling, I think, even more than the desire for increased educational excellence, which prompted our official chieftains to open the public service generally to competitive examination, so that they might rid themselves of the incubus of patronage. For almost any clerkship in the Civil Service almost any aspirant may now compete.

But in regard to these young women, a nomination is still made by some officer high in the department. I will not name Lord A. or Sir C. B., lest the unfortunate official pundit should be at once overwhelmed with applications by young ladies who read GOOD WORDS. As vacancies occur from six to a dozen are nominated together, and the fortunate ones -- not as yet quite fortunate -- have to submit themselves on a fixed day to tender mercies of Sir George Dasent and the other official examiners at Westminster. They are examined in reading, writing and arithmetic, and if they come up to a given standard then they are appointed on probation. But in addition to this there must have been medical approval, and for this and other purposes the telegraph department keeps a doctor of its own. And references are made as to character to three householders. [p. 31] In regard to these references we cannot but feel how hard it would be -- how almost impossible -- for any tender-hearted householder not to say a kind word.

But after the terrors of the examination, there are the subsequent terrors of the telegraph school. It is to be understood that no girl is allowed to enter after eighteen, and that they may become candidates at fourteen, so that the schooling is for the most part undergone at an age appropriate for tuition. The school is in Telegraph Street near Moorgate Street, and here telegraphy is inculcated for a period of two or three months. If a poor girl cannot learn the art, there is an end of the matter. If by that time she has gone so far as to show that she probably will learn it, she is sent to the big room at the top of the building in St. Martin's-le-Grand. Here she begins to receive wages. During these schools days she receives nothing, nor does she perform any service, but she receives her tuition gratis.

On her first entrance into the great world of the telegraph office -- that which is to be her world till she becomes a married woman, or during her life of celibacy -- she is put in possession of 8s. a week. But at this period she is hardly of much use as a telegraphist. During half her day she still undergoes instruction, performing light services about the office for the other half. Then when she is declared to be competent, she is seated proudly at her table, becomes a full-fledged government clerk, and is made the mistress of a weekly stipend of 12s.

From this time her duty consists in sending and receiving telegrams, or rather in passing on the telegrams which other public servants have received in other parts of the world. A telegram, for instance, from New Zealand to the Brazils would pass through this room -- or from Hammersmith to Poplar, or from San Francisco to Sydney, or from Liverpool to Southampton. But no one desiring to send a message goes here, nor are the messenger boys dispatched by these young women. They live secluded and apart, in a world of their own, harassed by no interruptions from without, and might, for aught that they feel in the matter, be accelerating cornmunications from one star to another. As I have said before, it is not my purpose here to explain the various systems of telegraphy used, but there are two modes -- very distinct as far as the aptitudes and capabilities of the young women are concerned; that, namely, by eye, and that by ear. The former may be learned almost by any one who can learn to read -- though as some pupils can read well and rapidly, while others hardly get beyond an elementary use of their letters so, of course, it will be with those who learn the alphabet of the wires. The second system, that by ear, can only be acquired by those whose organs of hearing are subtle and appreciative. And as there is a preference at present for those tinkling sounds by which words can be noted coming from a distance of as many thousand miles as the world is round -- as there is less labour and cost in this method, the clerk receiving the sounds without any interposition of marked paper -- they who are so gifted are held to be the most useful. No difference in pay is made, nor has it been acknowledged to me that the ear-gifted girl is better off than she who is less fortunate; but I cannot but think that higher capability will in the long run lead to higher rewards in the Telegraph Office, as in all other positions.

After three years of service the wages average 16s.a week and then it is supposed that the girl is fully able to support herself, that is, she can then pay, not only for her clothes and her food, but an adequate proportion of the other expenses of the home she may occupy. Of the total number employed I found that the average wages were at the period of my inquiry 18s. a week, and that the maximum wages of those working at the desks were 30s. The wages are paid once a fortnight, on every alternate Friday. The average will of course become higher than it is at present, as the whole thing is new, having been commenced in the service of the Crown within the last eight years. The greater number of the girls live with their families, and not unfrequently two or three sisters are employed together. I was assured that in many cases these girls had thus become the support of their parents. There are thirty female superintendents at higher salaries, and to these offices the clerks are of course eligible; and there is one matron over them all, to whom I presume is confided those delicate questions as to propriety and discipline at which I have hinted.

Thus I have told what these young women get in direct payment. In a rough way, it may be taken at 18s. a week per head. But there are other comforts attached to the office, which should be named. In most employments, when illness comes, wages cease. It is terrible that it should be so; but it is a necessity. The farmer who has to make a profit out of his labourers' work cannot afford to be generous; nor can the ordinary [p. 32] shopkeeper exercise such generosity over a lengthened period. The larger the business the greater may be the benevolence, because extended operations permit of systematized calculation. If two hundred people be employed the average sickness may be known, and wages may be so proportioned as to allow a margin for misfortune. The man in health will know that he receives something less in order that in sickness he may not be utterly desolate. But with the government the field is so large and the capital at command so unlimited, that benevolence may be extended as far as judgment may think fit; and as the judges in the matter do not suffer in their own pockets -- have in fact the exquisite pleasure of being benevolent at the expense of the nation -- the probability is that if there be a fault it will be on the side of philanthropy. The arrangement among the young women of whom we are speaking is as follows. They who are absent from illness receive two-thirds of their wages for a period not exceeding six months, and during this time they enjoy or may enjoy, the gratuitious services of the official doctor. After six months they are put upon half wages for some further period, varying according to circumstances. Perhaps nine months may see the end of official forbearance, or it may in peculiar cases be extended to twelve. I doubt whether any private service can offer such advantages. And then there is a luxury for ill health, which as a rule, can only be provided for the opulent. There are places for five telegraph clerks at Hastings and Brighton -- two at the former sea-side resort and three at the latter -- kept for these London girls. When the doctor thinks that a girl's health may be recruited by sea air, she is sent for a month to one of these places. Her railway fare is paid for her, she has 2s. a day extra for extra expenses, and she is required to work only for six hours a day, instead of eight as she does at the central office. There is no difficulty in keeping these five places filled. It should be added to this that all the females have leave of absence for a fortnight every year, during which time they have their full wages.

And then there are pensions. The scheme on which these are given is that which governs the whole Civil Service generally. At sixty years of age these public servants are entitled to a pension, without reference to further capacity for work; and in cases of permanent loss of health pensions are granted after ten years' service. I should rather say that pensions are allotted, for thiere is no grant in the matter, the allowance being one of right as much as are the wages; and the pension amounts to one-sixtieth of the existing wages for each year of service; so that a telegraph clerk who has worked for thirty years and was then earning 30s. a week would have a life pension of thirty-sixtieth, or one half, amounting to 15s. a week; if for forty years of 20s., or two-thirds. No pension goes beyond two-thirds of the wages. But even before the ten years have run out a gratuity is given on leaving the service, if the clerk be compelled to go by permanent ill health.

The work is for eight hours a day, which eight hours are consecutive; but out of this time half an hour is allowed for dinner. In the establishment, on the same floor, and close to the big room, there is a kitchen and there are eating-rooms. Here the girls can order what they please from the card of the day, and can have a thoroughly good hot meal for about 9l. For 6d. they can have a much better dinner than falls to the lot of, I fear, most workers in the metropolis. For 6d. they can have hot meat, vegetables, and bread, though perhaps the ninepenny portion may be more suitable to strong and growing girls. But if the cost for this be too much, they can bring their own food with them, and have it heated or cooked on the premises for nothing.

The hours of work for the females are from eight A.M. to eight P.M., each being on duty eight consecutive hours out of these twelve. Some may come at eight and go off at four; others at ten and go off at six, and so on. In this way the whole force must be in the building during the middle of the day, when there is greatest press of work, and at this period of course the relays of diners go to the banquet. Then after five P.M. there comes the necessity for tea. To all those of them who are kept on duty after that hour tea is brought at their desk-tea and bread-and-butter; and for that no charge is made. The generosity of the department in the matter of tea is perhaps less conspicuous than its administrative economy; for it has been found that more is saved in time by keeping the girls, at their desks than is lost in the price of the comforts supplied.

Eight hours of daily attendance, with half an hour allowed out of it, and the work all done sitting! To those who know what is the nature of work of a young woman behind the counter of a counter of a shop -- who is not allowed to sit lest she should seem to be neglecting her business, who is not allowed to sit lest it should appear that the shop is not doing a good trade, and whose attendance is seldom less than ten hours a day, [p. 33] and sometimes I fear, much more -- surely these arrangements will seem to be beneficent, humane, and praiseworthy. I ought to add here that there is no Sunday work whatever for the female operators.

And how do they all behave? And if they misbehave what is done to them? And of what nature may be the misbehaviour which most frequently interferes with the good order of this Paradise of female stationary messengers? This Paradise cannot be so perfect but what there should be occasionally be a Peri to be punished. As I explained late attendance was the first named. Minutes in the morning slip so easily away, especially when the question is one of rising out of bed! Every minute of late attendance is entered in a black book, because, or as was explained to me, the late attendance of a girl might too probably involve the late dispatch of a message. And how would it be if some gentleman who wanted his horse at the covert-side punctually at eleven should lose his run with the foxhounds because some lady found herself too comfortable in bed. Therefore the rules are very strict. If a total of thirty minutes in a month be marked against any girl, she is called upon to do extra work without pay. Money fines are not inflicted, except in rare cases and then only by the Secretary's order, -- the Secretary being the Secretary of the General Post office, an officer of majestic power outside the Telegraph Office, who may be supposed to be a sort of Jupiter up in the clouds. It is alwavs well that punishment should seem to come from some inscrutable and awful power at a distance. If such irregularity should be perpetual -- what we may call obstinate, or at any rate incurable -- then of course must come the last sad step of dismissal.

But was there any flirting? I was very anxious on that head when I saw the young men. No; -- I was assured that there was none to speak of; and my informant seemed to think that that matter, which was certainly one of difficulty, had been managed rather well. When I heard that there was nothing of the kind, I fear that there came across my mind insensibly some feeling of diminished respect for the young men. But when the matter was explained to me -- how the difficulty had been "managed " -- that injustice passed away from me. It has been told how these telegraph girls work between the hours of eight in the morning and eight in the evening. But the work in the office is of course continuous during the twenty-four hours. It is much lighter at night than during the day, but there is always work. The night-work is done entirely by the men, as is also part of the day-work. It will be readily understood that the day-work is the much more popular. But should a young man show himself disposed to be too agreeable during the day, no fault is found with him, nothing is said about it, but his services are simply required during the night instead. The arrangement is probably understood, and is at any rate effective.

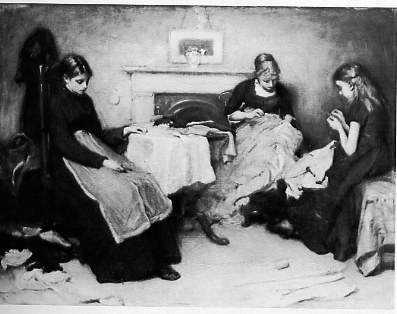

"May they talk?" I asked. Now I certainly had heard them talking -- a low hum of cheery young female voices, very pleasant to the ear. "And may they read, when there are no messages coming and going, or do a stitch of needlework?" And when mesages are coming and going the operator may not speak or be spoken to. And as in the press of the days, messages are always coming and going, and as, of course, the work is so arranged that there shall be as few idle minutes as possible, the talking is probably much reduced. But I did not feel so absolutely convinced about the talking as I had been about the flirting. If two girls of twenty can be got to sit close to each other without talking, human nature must have been changed up in the Telegraph Office. As to books and needlework, all such trivial occupations are absolutely tabooed till six P.M. Certainly during the two visits that I paid to the establishment I saw neither the one nor the other in the big room, though I found girls reading outside it during the half hour allowed for dinner. After six, when the work becomes less, and there may be many minutes of enforced idleness between this and the other message, then a handkerchief may be somtimes hemmed or a novel read.

And about friends -- visitors? Visitors I found were altogether forbidden. This seems to be a law which may never be infringed. The girls, I suppose, are not prisoners. In a matter of life or death, or perhaps even in affairs of lighter importance, access may be of course obtained through the interposition of superintendents. But, in an ordinary way, such a creature as a visitor is never seen upon that floor of the building; and the reason for this strict rule is not only the loss of time which would be necessitated -- though that might be reason enough -- but the nature of the occupation. Secrecy is essential. There seems to be no ground for fearing that any undue use is ever made of those multitudinous communications [p. 34] which are always passing under the eyes or through the ears of these women. But the temptation might be great if any outside sinner were able to hold free communication with that room at any time. Therefore there are no visitors.

"Then, practically, I said, "there is no misconduct?" For that seemed to be the conclusion to which I was brought from what I had heard. I asked the question probably with some little shade of doubt in my tone. "Come," said I; "how many dismissals did you have during the last year?" For I had on this ground known much of the Civil Service myself, and had been aware that in dealing with large bodies of men the exercisers of discipline must occasionally have recourse to that last means of declaring that obedience and order are indispensable. "Dismissal?" said my friend; "yes, we have had a dismissal. Miss -- was dismissed. But it seems to be a long time ago. I'll get the books." The books were got, and it appeared that the unfortunate one named had been sent away at some time in 1873! There had been no dismissal since.

There are supposed from a body of public servants as large as a regiment, -- numbering over eight hundred persons, -- there had been one dismissal in four years! You, Mr. Editor, are much concerned with the conduct of a large population in a large city. What do you think of this representation as to the conduct of eight hundred young women in the middle of the metropolis? To many readers, to those who have not had an opportunity of knowing how work is done, or how it is occasionally left undone, this perhaps may not seem to be very significant. But they who have had aught to do with the employment of many persons, whether in the Civil Service or in private enterprises, will, I think, acknowledge that this shows an amount of success over which there may well be some triumphant rejoicing. We have heard a good deal of the incompetence of young women for certain work at which they have been tried. They are supposed to be less constant to their duties, more prone to change, and less reliable -- I do not mean less trustworthy, and, therefore, I use a word to which strong objection has been lately made -- less reliable than men. To one objection they are certainly open. They are prone to get married, and when married they generally leave their employment. Whereas a young man when he is married is by that step only the more closely bound to his employers. But the history of this telegraph work, as far as it has yet been carried, seems to show, that when adequate care is taken that the physical capacities of women shall not be overtaxed, and that work be found of a nature suitable to them, they can be employed with equal advantage to the employer and to themselves. But in regard to their conduct, the result of my inquiry was so cheering that I think that it ought to be made public. In regard to health, as affecting their attendance, I am not surprised to find that they fall somewhat behind the men. The absence of the females on this ground amounted to five and one half per cent. on the number -- of the males to two and a half per cent.

I have stated that the number of telegraph girls to be eight hundred and forty-three in the General Post Office; but throughout London there are two hundred and sixty-eight others at various offices, who are paid by the Crown, making the total number eleven hundred and eleven. This does not include a class of young women who are employed and paid by the letter-receivers of the metroplis, and who are not in the direct service of the Crown. There are supposed to be something above a hundred and fifty of them, so that the total number of females employed on this duty in the metropolis may be taken to be something over twelve hundred and fifty.

I wish I could think that the number might be speedily increased; but that I fear cannot for sometime be the case. In order that the burden of night-work on the men may be lessened, it will be necessary to increase the number of men on the day-work. If for instance, there be always three hundred men on night-work and one hundred on day-work, each man could only have one night off in four, whereas if there were three hundred on day-work and three hundred on night-work, making six hundred altogether, each man would work only on alternate nights. I fear, therefore, that a small diminution of the number of female clerks may take place at the central office in order to provide a greater proportion of day-work for the men.

I do not like to conclude these remarks without observing how much the telegraph department of the General Post Office owes to the care and intelligence of its present chief, Mr. Fischer, a German gentleman, who, having been heretofore in the employment of one of the large telegraph companies, became a servant of the British Crown when the telegraph services were bought by the Government.

1 Anthony Trollope, "The Young Women at the London Telegraph Office," Good Words, June 1877, as reproduced in Miscellaneous Essays and Reviews, introd. Michael Y. Mason. New York: Arno Press, 1981.

2: