The most difficult thing that a man has to do is to think. There are many who can never bring themselves really to think at all, but do whatever thinking is done by them in a chance fashion, with no effort, using the faculty which the Lord has given them because they cannot, as it were, help themselves. To think is essential, all will agree. That it is difficult most will acknowledge who have tried it. If it can be compassed so as to become pleasant, brisk, and exciting as well as salutary, much will have been accomplished. My purpose here is to describe how this operation, always so difficult, often so repugnant to us, becomes easier out among the woods, with the birds and the air and the leaves and the branches around us, than in the seclusion of any closet.

But I have nothing to show for it beyond my own experience, and no performances of thought to boast of beyond the construction of combinations in fiction, countless and unimportant as the sand on the sea-shore. For in these operations of thinking it is not often the entire plot of a novel, -- the plot of a novel as a whole, -- that exercises the mind. That is a huge difficulty; -- one so arduous as to have been generally found by me altogether beyond my power of accomplishment. Efforts are made no doubt, -- always out in the open air, and within the precincts of a wood if a wood be within reach; but to construct a plot so as to know, before the story is begun, how it is to end, has always been to me a labour of Hercules beyond my reach. I have to confess that my incidents are fabricated to fit my story as it goes on, and not my story to fit my incidents. I wrote a novel once in which a lady forged a will; but I had not myself decided that she had forged it till the chapter before that in which she confesses her guilt. In another a lady is made to steal her own diamonds, -- a grand tour-de-force, as I thought, -- but the brilliant idea only struck me when I was writing the page in which the theft is described. I once heard an unknown critic abuse my workmanship because a certain lady had been made to appear too frequently in my pages. I went home and killed her immediately. I say this to show that the process of thinking to which I am alluding has not generally been applied to any great effort of construction. It has expended itself on the minute ramifications of tale-telling; -- how this young lady should be made to behave herself with that young gentleman; -- how this mother or that father would be affected by the ill conduct or the good of a son or a daughter; -- how these words or those other would be most appropriate and true to nature if used on some special occasion. Such plottings as these, with a fabricator of fiction, are infinite in number as they are infinitesimal in importance,-- and are therefore, as I have said, like the sand of the sea-shore. But not one of them can be done fitly without thinking. My little effort will miss its wished-for result, unless I be true to nature; and to be true to nature I must think what nature would produce. Where shall I go to find my thoughts with the greatest ease and most perfect freedom?

Bad noises, bad air, bad smells, bad light, an inconvenient attitude, ugly surroundings, little misfortunes that have lately been endured, little misfortunes that are soon to come, hunger and thirst, overeating and overdrinking, want of sleep or too much of it, a tight boot, a starched collar, are all inimical to thinking. I do not name bodily ailments. The feeling of heroism which is created by the magnanimity of overcoming great evils will sometimes make thinking easy. It is not the sorrows but the annoyances of life which impede. Were I told that the bank had broken in which my little all was kept for me I could sit down and write my love story with almost a sublimated vision of love; but to discover that I had given half a sovereign instead of sixpence to a cabman would render a great effort necessary before I could find the fitting words for a lover. These little lacerations of the spirit, not the deep wounds, make the difficulty. Of all the nuisances named noises are the worst. I know a hero who can write his leading article for a newspaper in a club smoking-room while all the chaff of all the Joneses and all the Smiths is sounding in his ears; -- but he is a hero because he can do it. To think with a barrel organ within hearing is heroic. For myself I own that a brass band altogether incapacitates me. No sooner does the first note of the opening burst reach my ear than I start up, fling down my pen, and cast my thoughts disregarded into the abyss of some chaos which is always there ready to receive them. Ah, how terrible, often how vain, is the work of fishing, to get them out again! Here, in our quiet square, the beneficent police have done wonders for our tranquillity not, however without creating for me personally a separate trouble in having to encounter the stern reproaches of the middle-aged leader of the band when he asks me in mingled German and English accents whether I do not think that he too as well as I, -- he with all his comrades, and then he points to the nine stalwart well-cropped, silent and sorrowing Teutons around him, -- whether he and they should not be allowed to earn their bread as well as I. I cannot argue the matter with him. I cannot make him understand that in earning my own bread I am a nuisance to no one. I can only assure him that I am resolute, being anxious to avoid the gloom which was cast over the declining years of one old philosopher. I do feel, however, that this comparative peace within the heart of a huge city is purchased at the cost of many tears. When, as I walk-abroad, I see in some small crowded street the ill-shod feet of little children spinning round in the perfect rhythm of a dance, two little tots each holding the other by their ragged duds while an Italian boy grinds at his big box, each footfall true to its time, I say to myself that a novelist's schemes, or even a philosopher's figures, may be purchased too dearly by the silencing ot the music of the poor.

Whither shall a man take himself to avoid these evils, so that he may do his thinking in peace -- in silence if it may be possible? And yet it is not silence that is altogether necessary. The wood-cutter's axe never stopped a man's thought, nor the wind through the branches, nor the flowing of water, nor the singing of birds, nor the distant tingling of a chapel bell. Even the roaring of the sea and the loud splashing of the waves among the rocks do not impede the mind. No sounds coming from water have the effect of harassing. But yet the sea-shore has its disadvantages. The sun overhead is hot or the wind is strong -- or the very heaviness of the sand creates labour and distraction. A high road is ugly, dusty, and too near akin to the business of the world. You may calculate your five per cents. and your six per cents, with precision as you tramp along a high road. They have a weight of material interest which rises above dust. But if your mind flies beyond this; -- if it attempts to deal with humour, pathos, irony, or scorn, you should take it away from the well-constructed walks of life. I have always found it impossible to utilise railroads for delicate thinking. A great philosopher once cautioned me against reading in railway carriages. "Sit still," said he, "and label your thoughts." But he was a man who had stayed much at home himself. Other men's thoughts I can digest when I am carried along at the rate of thirty miles an hour; but not my own.

Any carriage is an indifferent vehicle for thinking, even though the cushions be plump, and the road gracious, -- not rough nor dusty, -- and the horses going at their ease. There is a feeling attached to the carriage that it is there for a special purpose, -- as though to carry one to a fixed destination; and that purpose, hidden perhaps but still inherent, clogs the mind. The end is coming, and the sooner it is reached the better. So at any rate thinks the driver. If you have been born to a carriage, and carried about listlessly from your childhood upwards, then, perhaps, you may use it for free mental exercise; but you must have been coaching it from your babyhood to make it thus effective.

On horseback something may be done. You may construct your villain or your buffoon as you are going across country. All the noise of an assize court or the low rattle of a gambling table may thus be arranged. Standing by the covert side I myself have made a dozen little plots, and were I to go back to the tales I could describe each point at the covert side at which the incident or the character was moulded and brought into shape. But this, too, is only good for rough work. Solitude is necessary for the task we have in hand; and the bobbing up and down of the horse's head is antagonistic to solitude.

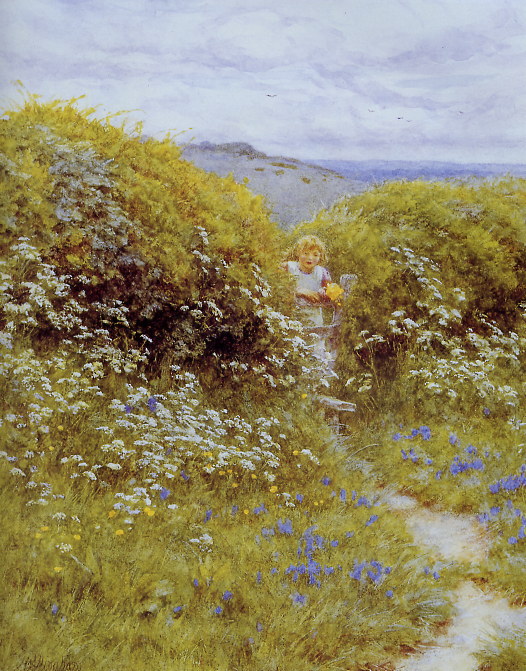

I have found that I can best command my thoughts on foot, and can do so with the most perfect mastery when wandering through a wood. To be alone is of course essential. Companionship requires conversation, -- for which indeed the spot is most fit; but conversation is not now the object in view. I have found it best even to reject the society of a dog, who, if he be a dog of manners, will make some attempt at talking. And though he should be silent the sight of him provokes words and caresses and sport. It is best to be away from cottages, away from children, away as far as may be from other chance wanderers. So much easier is it to speak than to think that any slightest temptation suffices to carry away the idler from the harder to the lighter work. An old woman with a bundle of sticks becomes an agreeable companion, or a little girl picking wild fruit. Even when quite alone, when all the surroundings seem to be fitted for thought, the thinker will still find a difficulty in thinking. It is not that the mind is inactive, but that it will run exactly whither it is not bidden to go. With subtle ingenuity it will find for itself little easy tasks instead of settling itself down on that which it is its duty to do at once. With me, I own, it is so weak as to fly back to things already done, -- which require no more thinking, which are perhaps unworthy of a place even in the memory, -- and to revel in the ease of contemplating that which has been accomplished rather than to struggle for further performance. My eyes which should become moist with the troubles of the embryo heroine, shed tears as they call to mind the early sorrow of Mr. --, who was married and made happy many years ago. Then, -- when it comes to this, -- a great effort becomes necessary, or that day will for him have no results. It is so easy to lose an hour in maundering over the past, and to waste the good things which have been provided in remembering instead of creating!

But a word about the nature of the wood! It is not always easy to find a wood, and sometimes when you have got it, it is but a muddy, plashy, rough-hewn congregation of ill-grown trees, -- a thicket rather than a wood, -- in which even contemplation is difficult and thinking is out of the question. He who has devoted himself to wandering in woods will know at the first glance whether the place will suit his purpose. A crowded undergrowth of hazel, thorn, birch, and alder, with merely a track through it, will by no means serve the occasion. The trees around you should be big and noble. There should be grass at your feet. There should be space for the felled or fallen princes of the forest. A roadway, with the sign of wheels that have passed long since, will be an advantage, so long as the branches above head shall meet or seem to meet each other. I will not say that the ground should not be level, lest by creating difficulties I shall seem to show that the fitting spot may be too difficult to be found; but, no doubt, it will be an assistance in the work to be done if occasionally you can look down on the tops of the trees as you descend, and again look up to them as with increasing height they rise high above your head. And it should be a wood, -- perhaps a forest, -- rather than a skirting of timber. You should feel that, if not lost, you are lose-able. To have trees around you is not enough unless you have many. You must have a feeling as of Adam in the garden. There must be a confirmed assurance in your mind that you have got out of the conventional into the natural, -- which will not establish itself unless there be a consciousness of distance between you and the next ploughed field. If possible you should not know the East from the West, or, if so, only by the setting of the sun. You should recognise the direction in which you must return simply by the fall of water.

But where shall the wood be found? Such woodlands there are still in England, though, alas, they are becoming rarer every year. Profit from the timber-merchant or dealer in firewood is looked to, or else, as is more probable, drives are cut broad and straight, like spokes of a wheel radiating to a nave or centre, good only for the purposes of the slayer of multitudinous pheasants. I will not say that a wood prepared, not as the home but the slaughter-ground of game, is altogether inefficient for our purpose. I have used such even when the sound of the guns has been near enough to warn me to turn my steps to the right or to the left. The scents are pleasant even in winter, the trees are there, and sometimes even yet the delightful feeling may be encountered that the track on which you are walking leads to some far off vague destination, in reaching which there may be much of delight because it will be new, -- something also of peril because it will be distant. But the wood if possible should seem to be purposeless. It should have no evident consciousness of being there either for game or fagots. The felled trunk on which you sit should seem to have been selected for some accidental purpose of house-building, as though a neighbour had searched for what was wanting and had found it. No idea should be engendered that it was let out at so much an acre to a contractor who would cut the trees in order and sell them in the next market. The mind should conceive that this wood never had been planted by hands, but had come there from the direct beneficence of the Creator, -- as the first woods did come, -- before man had been taught to recreate them systematically, and as some still remain to us, so much more lovely in their wildness than when reduced to rows and quincunces, and made to accommodate themselves to laws of economy and order.

England, dear England, -- and certainly with England Scotland also, -- has advanced almost too far for this. There are still woods, but they are so divided, and marked, and known, so apportioned out among gamekeepers, park rangers, and other custodians, that there is but little left of wildness in them. It is too probable that the stray wanderer may be asked his purpose; and if so, how will it be with him if he shall answer to the custodian that he has come thither only for the purpose of thinking? "But it's here my lord turns out his young pheasants!" "Not a feather from the wing of one of them shall be the worse for me," answers the thinker. "I dun-na know," says the civil custodian; "but it's here my lord turns out his young pheasants." It is then explained that the stile into the field is but a few yards off, -- for our woodland distances are seldom very great, -- and the thinker knows that he must go and think elsewhere. Then his work for that day will be over with him. There are woods, however, which may with more or less of difficulty be utilised. In Cumberland and Westmoreland strangers are so rife that you will hardly be admitted beyond the paths recognised for tourists. You may succeed on the sly, and if so the sense of danger adds something to the intensity of your thought. In Northamptonshire, where John the planter lived, there are miles of woodland, -- but they consist of avenues rather than of trees. Here you are admitted and may trespass, but still with a feeling that game is the lord of all. In Norfolk, Suffolk, and Essex the gamekeepers will meet you at every turn, -- or rather at every angle, for turns there are none. The woods have been all re-fashioned with measuring rod and tape. Two lines crossing each other, making what they call in Essex a four-want way, has no special offence, though if they be quite rectangular they tell something too plainly of human regularity, but four lines thus converging and radiating, displaying the brazen-faced ingenuity of an artificer, are altogether destructive of fancy. In Devonshire there are still some sweet woodland nooks, shaws, and holts, and pleasant spinneys, through which clear water brooks run, and the birds sing sweetly and the primroses bloom early, and the red earth pressing up here and there gives a glow of colour -- and the gamekeeper does not seem quite as yet to dominate everything Here, perhaps, in all fair England the solitary thinker may have his fairest welcome.

But though England be dear, there are other countries not so small, not so crowded, in which every inch of space has not been made so available either for profit or for pleasure, in which the woodland rambler may have a better chance of solitude amidst the unarranged things of nature. They who have written and they who have read about Australia say little and hear little as to its charm of landscape, but here the primeval forests running for uninterrupted miles, with undulating land and broken timber, with ways open everywhere through the leafy wilderness, where loneliness is certain till it be interrupted by the kangaroo, and where the silence is only broken by the noises of quaint birds high above your head, offer all that is wanted by him whose business it is to build his castles carefully in the air. Here he may roam at will and be interrupted by no fence, feel no limits, be wounded by no art and have no sense of aught around him but the forest, the air and the ground. Here too he may lose himself in truth till he shall think it well if he come upon a track leading to a shepherd's hut.

But the woods of Australia, New Zealand, California, or South Africa are too far afield for the thinker for whom I am writing. If he is to take himself out of England it must be somewhere among the forests of Europe. France has still her woodlands; -- though for these let him go somewhat far afield, nor trust himself to the bosky dells through which Parisian taste will show him the way by innumerable finger posts. In the Pyrenees he may satisfy himself, or on the sides of Jura. The chesnut groves of Lucca, and the oak woods of Tuscany are delightful where the autumnal leaves of Vallombrosa lie thick, -- only let him not trust himself to the mid-day sun. In Belgium, as far as I know it, the woods are of recent growth, and smack of profitable production. But in Switzerland there are pure forests still, standing or appearing to stand as nature caused them to grow, and here the poet or the novelist may wander and find all as he would have it. Or, better still, let him seek the dark shadows of the Black Forest, and there wander, fancy free, -- if that indeed can be freedom which demands a bondage of its own.

Were I to choose the world all round I should take certain districts in the Duchy of Baden as the hunting ground for my thoughts. The reader will probably know of the Black Forest that it is not continual wood. Nor, indeed, are the masses of timber, generally growing on the mountain sides, or high among the broad valleys, or on the upland plateaux, very large. They are interspersed by pleasant meadows and occasional cornfields, so that the wanderer does not wander on among them, as he does, perhaps hopelessly, in Australia. But as the pastures are interspersed through the forest, so is the forest through the pastures; and when you shall have come to the limit of this wood, it is only to be lured on into the confines of the next. You go upwards among the ashes and beeches, and oaks, till you reach the towering pines. Oaks have the pride of magnificence; the smooth beech with its nuts thick upon it is a tree laden with tenderness; the sober ash has a savour of solitude, and of truth; the birch with its may-day finery springing thick about it boasts the brightest green which nature has produced; the elm, -- the useless elm, -- savours of decorum and propriety; but for sentiment, for feeling, for grandeur, and for awe, give me the forest of pines. It is when they are round me that, if ever, I can use my mind aright and bring it to the work which is required of it. There is a scent from them which reaches my brain and soothes it. There is a murmur among their branches, best heard when the moving breath of heaven just stirs the air, which reminds me of my duty without disturbing me. The crinkling fibres of their blossom are pleasant to my feet as I walk over them. And the colours which they produce are at the same time sombre and lovely, never paining the eye and never exciting it. If I can find myself here of an afternoon when there shall be another two hours for me, safe before the sun shall set, with my stick in my hand, and my story half-conceived in my mind, with some blotch of a character or two, just daubed out roughly on the canvas, then if ever I can go to work, and decide how he and she, and they shall do their work.

They will not come at once, those thoughts which are so anxiously expected, -- and in the process of coming they are apt to be troublesome, full of tricks, and almost traitorous. They must be imprisoned, or bound with thongs, when they come, as was Proteus when Ulysses caught him amidst his sea-calves, -- as was done with some of the fairies of old, who would, indeed, do their beneficent work, but only under compulsion. It may be that your spirit should on an occasion be as obedient as Ariel, but that will not be often. He will run backwards, -- as it were downhill, -- because it is so easy, instead of upward and onward. He will turn to the right and to the left, making a show of doing fine work, only not the work that is demanded of him that day. He will skip hither and thither, with pleasant bright gambols, but will not put his shoulder to the wheel, his neck to the collar, his hand to the plough. Has my reader ever driven a pig to market? The pig will travel on freely, but will always take the wrong turning, and then when stopped for the tenth time, will head backwards, and try to run between your legs. So it is with the tricksy Ariel, -- that Ariel which every man owns, though so many of us fail to use him for much purpose, which but few of us have subjected to such discipline as Prospero had used before he had brought his servant to do his bidding at the slightest word.

It is right that a servant should do his master's bidding; and, with judicious discipline, he will do it. The great thinkers, no doubt, are they who have made their servant perfect in obedience, and quick at a moment's notice for all work. To them no adjuncts of circumstances are necessary. Solitude, silence, and beauty of surroundings are unnecessary. Such a one can bid his mind go work, and the task shall be done, whether in town or country, whether amid green fields, or congregated books or crowded assemblies. Such a master no doubt was Prospero. Such were Homer, and Cicero, and Dante. Such were Bacon and Shakespeare. They had so tamed, and trained, and taught their Ariels that each, at a moment's notice, would put a girdle round the earth. With us, though the attendant Spirit will come at last and do something at our bidding, it is but driving an unwilling pig to market.

But at last I feel that I have him, -- perhaps by the tail, as the Irishman drives his pig. When I have got him I have to be careful that he shall not escape me till that job of work be done. Gradually as I walk, or stop, as I seat myself on a bank, or lean against a tree, perhaps as I hurry on waving my stick above my head till with my quick motion the sweat-drops come out upon my brow, the scene forms itself for me. I see, or fancy that I see, what will be fitting, what will be true, how far virtue may be made to go without walking upon stilts, what wickedness may do without breaking the link which binds it to humanity, how low ignorance may grovel, how high knowledge may soar, what the writer may teach without repelling by severity, how he may amuse without descending to buffoonery; and then the limits of pathos are searched, and words are weighed which shall suit, but do no more than suit, the greatness or the smallness of the occasion. We, who are slight, may not attempt lofty things, or make ridiculous with our little fables the doings of the gods. But for that which we do there are appropriate terms and boundaries which may be reached but not surpassed. All this has to be thought of and decided upon in reference to those little plotlings of which I have spoken, each of which has to be made the receptacle of pathos or of humour, of honour or of truth, as far as the thinker may be able to furnish them. He has to see, above all things, that in his attempts he shall not sin against nature, that in striving to touch the feelings he shall not excite ridicule, that in seeking for humour he does not miss his point, that in quest of honour and truth he does not become bombastic and straight-laced. A clergyman in his pulpit may advocate an altitude of virtue fitted to a millennium here or to a heaven hereafter; -- nay, from the nature of his profession, he must do so. The poet too may soar as high as he will, and if words suffice to him, need never fear to fail because his ideas are too lofty. But he who tells tales in prose can hardly hope to be effective as a teacher unless he binds himself by the circumstances of the world which he finds around him. Honour and truth there should be, and pathos and humour, but he should so constrain them that they shall not seem to mount into nature beyond the ordinary habitations of men and women.

Such rules as to construction have probably been long known to him. It is not for them he is seeking as he is roaming listlessly or walking rapidly through the trees. They have come to him from much observation, from the writings of others, from that which we call study, -- in which imagination has but little immediate concern. It is the fitting of the rules to the characters which he has created, the filling in with living touches and true colours those daubs and blotches on his canvas which have been easily scribbled with a rough hand, that the true work consists. It is here that he requires that his fancy should be undisturbed; that the trees should overshadow him, that the birds should comfort him, that the green and yellow mosses should be in unison with him, -- that the very air should be good to him. The rules are there fixed, -- fixed as far as his judgment can fix them, and are no longer a difficulty to him. The first coarse outlines of his story he has found to be a matter almost indifferent to him. It is with these little plotlings that he has to contend. It is for them that he must catch his Ariel, and bind him fast; -- but yet so bind him that not a thread shall touch the easy action of his wings. Every little scene must be arranged so that, -- if it may be possible,-- the proper words may be spoken and the fitting effect produced.

Alas, with all these struggles, when the wood has been found, when all external things are propitious, when the very heavens have lent their aid, it is so often that it is impossible! It is not only that your Ariel is untrained, but that the special Ariel which you may chance to own is no better than a rustic Hobgoblin, or a Peaseblossom, or Mustard Seed at the best. You cannot get the pace of the race-horse from a farm-yard colt, train him as you will. How often is one prompted to fling one's self down in despair, and, weeping between the branches, to declare that it is not that the thoughts will wander, it is not that the mind is treacherous. That which it can do it will do; -- but the pace required from it should be fitted only for the farm-yard.

Nevertheless, before all be given up, let a walk in a wood be tried.

1 Anthony Trollope, "A Walk in a Wood," Good Words, June 1879, as reproduced in Miscellaneous Essays and Reviews, introd. Michael Y. Mason. New York: Arno Press, 1981, pp. 163-76.