LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, -- Though, perhaps, I ought in my address to name only the ladies, as it is to them exclusively that I have been asked to speak, -- I have been invited to come here to-night and to say something to you which may be encouraging, and at the same time, if possible, pleasant, as to the higher education of women. I am afraid that the pleasantness may be difficult to achieve, as, by the nature of the subject proposed to me, I must appear in the very outset to be finding fault with you. Now, I can have no possible right to do that. How can I be so bold as to assume that any lady in is in need of a higher education than she has at present acquired, seeing that up to this moment I have never been privileged with the acquaintance of any of the ladies of ................ [sic]? And then, why should I, as a man, knowing, as I well do know, how very deficient is the education of men, dare to imply that women especially require to be exhorted on this subject. Were it not that I have learned that, much as people object to be found fault with individually, they rather like it collectively, I should not dare to stand before you and address you on this matter. There is not one of you here to whom I could dare to say in her own drawing- room, -- Are you not wasting your life? --Are you not frittering away your time? -- Do you not let day follow day, heedless of a purpose? And yet that is what I am called upon to say to all of you together. Now really I don't know that any of you waste your time or fritter away your lives. Each of you may be living with a settled purpose of life strong to her as a rock of adamant.

But I suppose we may take it as granted that, whatever may be the requirements of .................. [sic], there is a vague but yet very universal feeling throughout England, that as women of the middle and upper classes have made their way out of the kitchen, in which they used to spend much of their time, they have allowed themselves to flutter too much in faineant drawing-rooms, or perhaps to linger too long amidst the business [p. 69] of toilet-chambers. That, I think, is the gravamen of the charge which is made as to women of the present day, -- much more by themselves than by men; and as to that I have plucked up my courage and now venture to address you, trusting that all of you will hear with equanimity what each separately would consider to be an impertinence.

But I must first declare that there was something very cruel, I may almost say barbarous, in asking me to undertake this task; -- me of all men; -- asking me, who am absolutely dependent in a great measure on the laziness of ladies for my daily bread, to come forward and preach that higher education which requires real labour. I have been asked to cut my own throat, -- and I am here to do it. If any lady in this room knows my name at all, or has ever heard of me, she has heard of me as a writer of novels. And if there be one thing that I am more imperatively bound by my present duty to tell you plainly than any other, it is this, -- that the reading of novels as a life's occupation must be utterly destructive of that energy which is required for high purposes. Now I think that is hard upon me. I think there must have been some special malice when I was asked to take an axe and hew away at the branch of the tree on which I am myself seated, to dash the bread from my own mouth, and the cup from my own lips. But I hope to prove that I have courage for the occasion, -- thinking perhaps that, in spite of all that I or others may say, novels will, after all, hold their own.

I will allude to novels again when speaking of literature generally. But it is perhaps expedient that you should in the first place think what it is that you mean to do, -- what triumph you wish to achieve, -- when you talk of the higher education of women. I am afraid that there are some who conceive that by some one grand effort, by a strong and instant resolution on the part of women generally, the thing may be done and the triumph at once brought home to them. Let the resolution be fixed and the struggle made, and women will become something very different from what they are now, -- infinitely more satisfactory to themselves, [p. 70] better able to hold their own in coping with men, and free from those faults of frivolity and languor of which they are now as a body not unfrequently disposed to accuse themselves. I think that there is such an idea abroad. I for one do not believe in any such grand effort. I do not put faith in any scheme by which women may suddenly be altered; -- and if I did I should be very much afraid of facing that alteration when it should come.

Let us suppose for a moment that all the ladies in should club together, -- or, perhaps, all the ladies in this room, instigated by some address much more powerful than mine will be, -- and were to settle on some tremendous curriculum in pursuit of knowledge, -- to be commenced, let us say, on next Monday. After next Monday not another novel to be read! That should be the first thing. Anybody mentioning the name of Mudie to be fined by two hours' extra Greek! No lady to spend above £30 a year on her dress. Every lady to be at the breakfast-table at 8 o-clock! An hour of Latin, an hour of French, and an hour of German before lunch; another hour of mathematics, another of history, and another devoted to Bible literature in the afternoon! Then an hour in the kitchen among soups and puddings, and an eighth hour in the evening devoted to making cloaks and petticoats for old women! That I should call a grand effort on the part of ..............[sic]. It would be strong evidence that some very moving spirit had been at work among you. But I, myself, when I heard the terms of that resolution, would be doubtful of any great good coming from it. We cannot alter our natures. At any rate we cannot alter them suddenly. I should be better pleased to hear that some little girl had quietly determined to limit herself to one novel a month, and had promised herself that she would write a French letter in good grammar to her father before the year was over.

I do not think that, in this matter of the education of women, the world, our world, -- the world, for instance, of ............... [sic], -- has gone altogether wrong; though it may not. perhaps, have gone altogether right. Very [p. 71] great progress has been gradually made; as would be admitted if we had readily at hand the means of comparing the knowledge of the present with that which was general among women, say two hundred years ago. The comparison has been made for us by a master-hand. Macaulay tells us that at that time, -- in the days of Charles II. -- the literary stores of a lady of a manor and her daughter consisted of a prayer-book and receipt-book; -- excellent books, but forming a limited library. "In the highest ranks," he says, "the English women of that generation were decidedly worse educated than they have been at any period since the revival of learning." "During the latter part of the seventeenth century the culture of the female mind seems to have been almost entirely neglected. If a damsel had the least smattering of literature, she was regarded as a prodigy. Ladies highly born, highly bred, and naturally quick-witted, were unable to write a line in their mother-tongue without solecisms and faults of spelling such as a charity girl would now be ashamed to commit." We have means, too, of knowing how very limited was the general information of those days, and how very much less was that of the women than of the men. I take it for granted that every lady now listening to me has a clearer idea of the governments of Russia and the United States, -- though their ideas may not be absolutely cloudless, -- than had ladies in the time of Charles II. of their own. You all know something of the present condition of France, something of the weakness of Spain, something of the strength of Germany. In those days nothing was known of foreign countries by ordinary English ladies or gentlemen. I may presume that most of you have read Shakespeare, Byron, and Scott, -- Scott, of course, because he wrote novels; but the ladies of England then knew, as a rule, nothing of the literature even of their own country. Consequently their minds had little on which to employ themselves, except the beef and puddings which their husbands and brothers ate, -- and their lovers. It was a feeble and a bad existence; -- much worse than that of those beneath them in the social [p. 72] sphere, who were called on to work for their daily bread. Now we have certainly made great progress since that. I do not want to make you believe that there is nothing more to be done than to go on as you are now going. If I thought that I should not be here at this moment. But I am far from being one of those who say that the education of women has been either stationary or retrogressive. I have generally found the conversation of an Englishwoman of four-and-twenty to be superior to that of a man of the same age.

But the fault is, I think, that with women education stops short at a certain very early period of life, and that after that the mind and the intelligence become lost in the liberty which is allowed to them. There is no bond, no law, by which the mind is forced into any labour. Books are at hand, -- books of course. It has come to be understood that a life without books is a degraded life indeed. That there should be intellectual pursuits is taken for granted. But all is vague. The thing to be done is not a fixed thing. Poetry is taken up; but the understanding of poetry is laborious. Music has been learned; but music comes to nothing without practice, and practice is laborious. It is the same with French, with history, -- with all those special studies which are attractive to the female mind -- botany, conchology, and the like. They require labour. The young female mind, just emancipated from tuition, is ambitious, would fain improve its powers and use itself; -- but to do so must encounter labour; and the human mind, the man's mind as well as the woman's, is disposed to turn away from labour that is not obligatory. That book of history is dropped from the hand on Monday morning, to be resumed on Monday evening, -- and on Monday evening it is forgotten. It is dropped again on Tuesday morning. Mr. Anthony Trollope's last novel suits better for the frame of mind on that special occasion. And so Mr. Anthony Trollope's last novel, or some tale of more thrilling interest, grows into daily request instead of that book of history. The father sees it and perhaps says a gentle word. The mother sees it and wishes it were otherwise. But the girl has been [p. 75] emancipated from her tutors, and neither father nor mother can endure to lessen the sweetness of home by words of reproach. So it goes on till the mind, intelligent as it is, becomes vague, loose, and unfitted for settled occupation. Then the friends of the young lady, and probably the young lady herself, become aware of the necessity of higher education for women! What we want is, I think, employment, -- mental employment and material employment also, -- for women whose circumstances do not require them to earn their daily bread.

What we do not want, -- I am now speaking my own opinion, and I do not know how far that may or may not be acceptable at .............. [sic], -- what we do not want is to assimilate men and women. And if we did want it there is, I think, a higher law than any that we can make which would prevent it. As we cannot turn a man into a woman, or endue him with that quicker appreciation and more sparkling intelligence which is the woman's privilege, so neither can we give to her the gift of persistent energy by which he does perform, and as been intended to perform, the work of the world. There is no doubt a very strong movement now on foot in favour of such assimilation, arising chiefly, as I think, from a certain noble jealousy and high-minded ambition on the part of a certain class of ladies who grudge the other sex the superior privileges of manhood. Why should not a woman, if she be capable, earn those rich rewards of fame, of position, and of wealth which men are on all sides obtaining for themselves? When I hear, as I often do hear, a woman urgent in this matter, anxious to press forward with her whole heart into the arena of the world's work, and thus to shake off a dependence which she feels, -- but I think wrongly feels, -- to be more abject than that of men, I am inclined to admire her while I oppose her. But I always must oppose her, I do know, -- I think I know that she is kicking against the pricks. Humanity has been at work for the last thousand years and more to relieve women from work, in order -- to put the matter roughly -- that man might earn the bread and woman guard and distribute it; that man might provide the [p. 74] necessities of life, and woman turn such provision to the best account. And that lesson comes direct from nature, -- or, in other words, from the wisdom of an all-wise and all-good Creator. It is to be seen everywhere, --in all the attributes, organs, capabilities, and gifts of the two sexes.

The question of women's rights, -- as it is called, -- is not one on which it is my purpose to dilate now. I have not been asked to come here to talk on that subject. But it is so likely to ally itself, in the minds of some, with that on which I am talking, that I have found it difficult not to say that I at least, in advocating higher education for women, am not advising any woman to think herself qualified to do the work of a man. Their occupations are as useful, as noble, as various; but I, at least, am convinced that they cannot in the long run be the same.

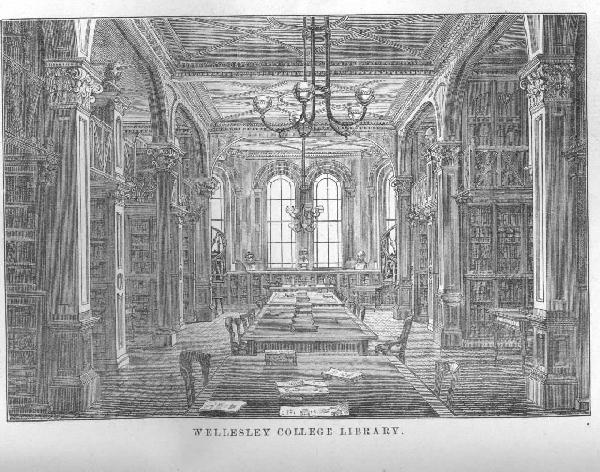

Nor do I think that the education of boys and girls should be the same, or that it should be carried on together. You are probably aware that this is a subject which has been very extensively discussed in America, where it has been supposed that women in this country, -- and indeed in Europe generally, -- have been specially injured in this, that they have been separated from their brothers and treated with a less allowance of general educational good things. The question is too long, too deep, and too dependent on physiological considerations for discussion here; but even in America it is now much doubted whether the system which is the best for the one is not apt to be injurious to the other. The attempt when made is made with the object of equalising the woman with the man, by giving the woman her share of those good things which have hitherto been monopolized by the man. But in this there is, I think, the error of supposing that what is good for the one must necessarily be good for the other. Independently of any question of physics, I for one should deplore a system of education which would create competition between the sexes. There are thousands of small household reasons which must crowd upon the minds of you all why that rivalry which is salutary between men, and [p. 75] between women also, should not be encouraged between men and women. It is not my purpose to decry the efforts of our friends in America, whose determination to make a good education the birthright of every child of their country demands all our praise; but I think I may venture to say that their propensity to carry on the education of boys and girls under the same roof, and in the same classes, will never become popular in this country. What we want for our sons we do not want for our daughters; and what we want for our daughters we do not want for our sons. Even if this feeling arise from national prejudices rather than from national wisdom, still the feeling with us is so strong that no attempt to overcome it will find favour in this country till the nature both of English men and English women has been changed.

I say as much as this because I would not have one of you here think that I have come among you to tell you that any want that you feel arises from the injustice of men in taking from you, by their greater physical strength, the good things of the world. It is a man's right in the world to be a man, and his duty to take upon his shoulders the great weight of the labour of the world, so that women may, as far as possible, be relieved from burdens too heavy for their strength. And it is a woman's right to be a woman, and her duty to utilise his earnings and minister to his comfort. We all know that accidents will happen in the best regulated families. Railway trains will not always keep their appointed hours. The meat will sometimes be a little over-done or a little under-done. The pear will not be quite ripe, or will be a little too ripe. In this great matter of the arrangement of men and women all does not run smoothly. There are some accidents, -- some trains late, some ill-cooked joints, -- some imperfect fruit. And as we all think more of the one day with an accident than of the ninety-nine untroubled days, of the one journey in which we were ill used than of the dozen on which we were properly conveyed, of the one leg of mutton that came up raw than those scores of legs of mutton which have elicited neither complaint nor praise, so do the [p. 76] few thousands of women who do not fall into the comfortable beaten paths of the world, obtain infinitely more notice than the millions upon whom the laws of our normal way of living act with normal efficacy. But, if we admit that the laws of life among us, such as they are, are good for the many, we should hardly be warranted either by wisdom or justice, in altering them for the proposed advantage of a few.

I think that we should divest our minds of the idea, -- certainly at this moment a prevalent idea, -- that that improvement in education which women want for themselves is to be obtained by assimilation on their part to men, either, as regards political privileges, social standing, or educational system. The two things are distinct; -- so much so that it may be that you think it unnecessary I should even insist on this distinction. But I differ so thoroughly from those who do not keep them distinct, that I cannot address you on the subject without insisting on the distinction. The men around us in the world who are demanding women's rights, -- and there are many such men, -- remind me very forcibly of the good-natured bear, who sat at the head of his friend, the man, when the man was asleep, and dashed a brick-bat at the fly which was disturbing the keeper's eyelids. The bear of course knocked out his friend's brains by his ill-tlmed but well- intended energy. Some of the women's friends are equally ill-judged. They are the friendly bears, and they see the flies disturbing your comfort. It does not go smoothly with you all. There is not quite enough of money, not quite enough of feminine occupation, -- not quite enough, perhaps of husbands: and therefore, according to your friend the bear, you are all to be thrown into the labour market, and hustle and tustle for your bread amidst the rivalry of men. I do not myself think that you can improve your chances in life in that way. I hope you will not allow the bear to protect your slumbers.

But we all are sure, -- you and I and the rest of us , -- that you may improve your chance of happiness by something that we call higher education. I have already said that I do not conceive that higher education is [p. 77] to be obtained by educating boys and girls after the same fashion; nor am I at all sure that it is to be reached by any great and fundamental or radical change in the education of girls. From day to day changes are being made which are not radical, and which are therefore much the safer. We must all acknowledge that very great changes have been made since those days of Charles II., of which Macaulay told us. Sometimes these changes have been too slow, and ladies who have had the charge of education have been a little too apt to cling to old ways. Sometimes they have been pressed on too eagerly, and more has been attempted than could be effected. We all of us know the old-fashioned girls' school, where the backboard and the graces are, perhaps, too much in vogue; and we know the new-fashioned school with its impossible curriculum of all the ologies. We have laughed at both, and some of us have grieved over both. And we are aware too, with reference to another mode of education, that with all the efforts that have been made to train governesses fit for their business, how many ladies attempt the difficult work of education who know nothing of the first principles of teaching. Things are very far from being perfect. Things are always very far from being perfect. But there cannot be any doubt that our girls schools have been very much improved, and are being improved; and that the difficult and delicate work of a governess is becoming a profession to which more and more care is being given year after year. I am inclined almost to doubt whether the improvement in girls' education up to the time at which they leave either their school or their school-room at home, has not gone on as quickly and as satisfactorily as we have had a right to expect.

Then, you will ask, what on earth have I come here to talk about? As to women's rights, I have discarded them altogether. I have told you that I am equally averse to the American system of educating boys and girls together, and that I think we should injure the health of our girls if we were to try it. And I have said also that as to our own methods of feminine education, I believe the progress to have been as quick as we [p. 78] had any right to expect. What, then, is it that there is to be done, in order that we may make some real progress towards that higher education of women which we desire?

And now, in trying to explain to you what it is necessary that we should do, I shall come to that part of my address which I hope you may forgive me collectively, though each of you would think it to be extremely impertinent if it were to be made to you separately. It is the use which you make of the education which has been given to you rather than the education itself which is in fault. Learned people often tell us that we use the word education wrongly. But we all know what we mean in its common use. We intend to speak of that tuition which we receive when we are, if I may employ a Latin phrase, "in statu pupillari." When we talk of education, we generally intend to talk of the teaching which is given to us when we are subject to the control of our teachers. But when we talk of higher education for boys or girls, -- or for men and women, -- we certainly imply something much more than that, and are contemplating that advanced improvement of the intelligence which the pupil should give to herself or himself under her or his own control. Now I think the question before us is, whether this most important duty is adequately done by the young women of the present time. And I think that the demand for the higher education of women which is being made in all places, implies a very general opinion that the duty is not performed as well as it might be.

I fear there can be but little doubt that general opinion is right in this. I am probably addressing myself to ladies upon the greater number of whom the chances of life have not imposed the duty of earning their own bread, and who are therefore placed in a peculiarly dangerous position as to the use which they may make of their time. At any rate it is of such that I think we chiefly speak when we talk of the higher education needed. I say chiefly, -- for no doubt among those who do earn their own bread, there are many to whom the same remarks will apply, because they too, though they [p. 79] do work for their bread, have nevertheless certain hours of the day at their own disposal. And here, -- at the period of life to which we are now alluding, -- begins the great difference which exists between sisters and their brothers. The young man as a rule has a life of work before him. Whether he perform his duty or neglect it, it is that to which he looks forward as the recognised duty of his life. The cases in which an unfortunate young man is intended to do nothing, nothing at all either in earning his bread or in taking care of the bread which others before him have earned for him, are luckily very few. Such young men, if there be any such, are among the most unfortunate of human creatures. It is not with their misfortune that we have to do at the present moment. But you, who are the sisters of men who immediately on leaving school or college have gone to the desk or the counting-house, who have become lawyers or clergymen, soldiers or sailors, doctors or merchants, have, when you left your schools or your schoolrooms, had no such obligations imposed on you. With them work has been a matter of course. They themselves have never doubted it. Has idleness been equally a matter of course with you? If it be so, if it must be a matter of course, then indeed it may be conceded that women have a right to complain of their lot in life.

I will allow you to laugh at me for reminding you of two lines of poetry which you have no doubt often heard, but which you probably will not have expected me to repeat to you to-night. The poet whom I am going to quote is perhaps not so popular in our houses now as he was once; --

"Satan finds some mischief still For idle hands to do."

The advice therein contained is somewhat homely and probably you may all have got to a time of life beyond that in which the lesson is made familiar. But I almost think that the whole mischief lies in the forgetting of that lesson.

It has become a fashion in these days, -- and a very [p. 80] pleasant fashion it is, -- to banish from our houses altogether a certain sternness of demeanour, a certain parental severity both of manner and of action, which even half a century ago used to prevail in our families. Fathers and mothers now live with their children on a very different footing from that which was then in vogue. The intercourse between them and their grown-up children is now almost that of equals. Something of reverence from the young to their elders of course there will be. At any rate there should be. Something too of dictation from the elder to the younger, -- though it is I think in these days very slight between mothers as I know them, and daughters as I know them. Far be it from me to deplore a change so sweet as this, -- or to say a word against a state of things that has added so much grace and happiness to our homes. I do not know anything in England so pretty as the slightness of the supremacy of a fair mother over a bevy of fair daughters. But as this delightful home familiarity and home equality has progressed, home discipline has, as a natural consequence, faded away, -- till in some homes it may be said no longer to exist.

And, -- it will be asked,-- why should there be need of discipline? If the girl is to be married say at twenty- four, will she not be better able to become the ruling spirit of her husband's house, if for the last four or five years she has been the mistress of her own actions and her own hours? Must it not be well that she should be thrown on her own conscience and her own responsibility at a time of life in which the law regards her as a woman complete? There is very much to be said on behalf of this doctrine of freedom. So much at any rate has been said and thought and felt that the doctrine has prevailed and the freedom has been established. There is no use in preaching against that now, -- nor on my part is there any desire to preach against it.

But that strict discipline which did exist, -- discipline after the absolute work of teaching is over, -- has gone. It is no longer the fashion of the country. Parents feel that they are no longer called upon to exercise it with the strictness to which they when young were perhaps [p. 81] subjected. And daughters would be surprised if they were called upon to submit to it. But I suppose no one will on that account be bold enough to say that there is no longer any need of discipline. Nature tells us that from our cradles to our graves we should be subject to certain laws; and that no breach of these laws can be made without the payment of penalties. In our early years the discipline is imposed by others. When we are, -- what is called grown up, -- we have to impose very much of it on ourselves. In these latter days we are "grown up" somewhat earlier than were our fathers and mothers. The self-discipline is required very soon. I will venture to ask the young ladies who hear me whether they are careful to impose it on themselves.

I am sure that they are all anxious for that higher education of women of which we are talking. Their presence here I take as proof of that. Nor indeed is such proof necessary. There is no lack of that ambition which prompts the desire; -- only of that further ambition which should create the work. You would all like to talk French and German as well as you do English, to have the best of our national poetry at your finger's ends, to be acquainted with the history of your own and other countries, and to find yourselves never at fault when general literature is discussed. Instrumental music, painting, singing, the construction of flowers, the habits of birds and insects, have all of them, no doubt, charms for some among you. You are probably not indifferent to the social condition of your neighbours. The comfort and well-ordering of your own families and households is of course a matter of interest to you. There is a desire to excel in all those pursuits by which a woman should gladden her own life and that of all those around her. But if the desire be there unaccompanied by energy to satisfy the desire, what can be the result but discontent and unhappiness?

If you will allow me I will give you a picture of the life of a young lady of my acquaintance, who I need not say shall be nameless. But as I must tell you some hard things of her, it may be well to assure you that [p. 82] she does not live any where near............. [sic]. She is a fair, sweet-tempered, good-hearted, healthy girl. Her parents are sufficiently well-to-do in the world and gave her a good education at a good school. She came home at eighteen -- to the inexpressible joy of her mother who had longed for so dear a daily companion, and to the delight of her father, who immediately began to spoil her by every indulgence to be thought of. She could read and write French fairly. She could play certain pieces on the piano well enough to please the ignorant. She had read as much as school girls generally do read; -- and in saying that I mean to imply that she had read a great deal. She is passionately fond of dancing, and dances beautifully. She was what I call a very good girl, -- affectionate, anxious to serve others, with no bad, sly tricks about her, and passionately devoted to her father and mother. Now, have I not described a pretty, pleasant, sweet young creature? She is -- or at any rate was, -- a pretty, pleasant, sweet young creature. And as she is now five-and-twenty I have often been surprised why she is not -- settled in life.

I know the house well, and have watched her from the day on which she came home. She was to be her mother's chosen companion. There was to be no more teaching, no more discipline, above all things no more scolding. The emancipated darling of the house was allowed to have everything her own way. You have all of you perhaps been emancipated darlings in your time, -- perhaps are so still, or if not, soon will be so, and at any rate understand what it is. I don't know a pleasanter phase of life. My young friend liked it extremely. Everybody flattered her. Her father was always caressing her. Her mother seemed to be her most obedient slave. I, who am the old-fogy friend of the family, -- most of you probably have such a friend in your houses, -- used to think it quite a privilege to have fun poked at me by this happy, charming, emancipated darling.

But I watched her from the first, and always had some fear, lest the emancipation should be too complete, -- too quick for her own power of turning it to [p. 83] advantage. I must acknowledge that in the first days of her emancipation I used to see about the house sundry signs of very excellent employment indeed. I remember a first volume of Hallam's Middle Ages that used to lie about, and can see now the cover of the German dictionary which she used, -- or intended to use. And there was a Globe Shakespeare, and a pet little volume of Longfellow. I knew them all. And the loose sheets of Gounod's music which she wanted for real practising I myself bought for her, when once, in a moment of enthusiasm, she told me that she was determined that she would play the piano well.

When I first heard that there was to be a subscription at Mudie's, I did not think much about it. Everybody has a subscription at Mudie's. It was very natural that some light reading should be required. I knew that Hallam and a German dictionary, even when supplemented by Shakespeare and Longfellow, would not quite suffice; but when I saw the hrst cargo that came down I did feel a little alarm. There were four three-volume novels, and I had not written one of them myself; -- fine spirit-stirring stories in which everybody lost everybody, and the rest were all murdered. I soon found that the box had come back again and that the set had been changed.

I once ventured to ask her when I saw her at eleven o'clock in the morning with one of Mudie's volumes in her hand, whether a later hour in the day would not be fitter for such reading, -- whether she should not put off her novels till she had done a little work. She answered me rather pertly, -- for the emancipated darling could be pert, -- that she did not see any difference in the hours of the day, that eleven in the morning was as good for a novel as for German, and eleven at night as good for German as for a novel. I can only say that I never saw her with the German dictionary at eleven o'clock at night, and that the German dictionary and volume of Hallam went very soon out of sight together. My little present of the music was I fear absolutely useless.

In sober truth, within three months of her emancipation the darling read nothing but novels ; -- and, as far [p. 84] as I could see had no other in-door occupation whatever. Then a worse time came, for I could perceive before long that she did not even read her novels. She only skipped through them, finding the labour of reading even them to be too much for her. To learn what were the names and positions in life of her heroes and heroines, what the nature of the troubles with which they were enveloped, and what at last became of them, -- that was enough for her. And in doing this she would pass hours and hours in a listless, vague, half-sleepy interest over the doings of these unreal personages. Interest, indeed, there was none, for the feeling soon descended to sheer curiosity. As far as I could see after a while she never opened another book. Even the Shakespeare and Longfellow were neglected. It soon came to pass that she could not be down early enough in the morning to give her father his cup of tea; -- and she has become too languid for walking. She can dance still, -- dance and read novels! These are the pursuits of my emancipated darling, and I do not see that the costly education which her father gave her will ever be of much use to her. She is twenty-five, and, as I have told you, not yet -- settled. Mucn as I love her I have almost begun to doubt whether she is fit for -- settling.

I hope that this description does not come home to any that hear me. I do not intend that it should. The emancipated darlings of ............ [sic] have, I do not doubt, employed their time better than my young friend. But when we talk of the need of higher education for women such a condition of life as that which I have attempted to describe is I think the chief danger which we have to fear. And it is not only the idleness of such an existence which we have to deplore, -- the terrible, listless, long-protracted idleness; but the state of mind which is engendered by such absence of occupa tion. Who among us has not known that vague, purposeless condition of feminine intellect in which the imagination is excited, but is not sufficiently excited for any creative power, for any real work, -- not sufficiently even for the understanding of true work? In this condition any real exercise of the mental faculties becomes [p. 85] an exertion too great to be endured, -- a labour too severe for the strength. Can any of you here say that I have exaggerated the picture? Do you not all reckon among your acquaintances some such emancipated darlings as her whom I have described.

But, lest you should think that in portraying for you the lamentable condition of the novel-reader, -- which is some-thing like that of the opium-eater, -- I have really cut my own throat and proved that there should be no such thing as a writer of novels, -- I will now say a word in favour of novels. And I may, perhaps, best do so by likening them to the athletic exercises of our young men. Nothing can be better than cricket, -- rowing, -- rackets, and the like; -- nothing can be better in the way of amusement. We who are fathers know that our sons and daughters must have recreation; -- and when we hear of a Boy of ours who has excelled at this or that sport we are proud of his prowess. We are proud of his prowess till we find that his recreation has taken the place of the work of his life; -- and then our pride gets a terrible fall. It is the same with novels and novel-reading for young women. Pray do not go home with the idea that I have told you that the German dictionary and Hallam should occupy all your time. Recreation is necessary for all of us. That now is recognised everywhere; -- but unfortunately the recognition has become so acceptable and so general, that some of us seem to think that there should be nothing but recreation. Now the truth is that amusements do not really amuse, that recreation ceases to recreate, and that play itself becomes worse than work, harder than work, when the search after them is made the one employment of life. My friend the emancipated darling, toiled dreadfully at her novels, and got, I think, no amusement from them at all. But novels if they be taken, -- as all our playthings should be taken, -- only in play hours, if they be used sparingly as sweetmeats, and not as though they were sufficient to supply the bread and meat of our daily lives, may I think be very good. If you will take some little trouble in the choice of your novels, the lessons which you will find taught in them [p. 86] are good lessons. Honour and honesty, modesty and self-denial, are as strongly insisted on in our English novels as they are in our English sermons. But to base your life on the reading of novels, -- to make that the chief work of the mind and intellect which God has given you; -- surely that must be very bad! Do you think that such an employment can be compatible with anything worthy of the name of higher education? Upon the whole I think it quite as well that that emancipated darling has not been -- settled.

In truth, it is to yourselves that you must look for this higher education of which you are in search. Classes, lecture-rooms, co-operation, and outside assistance, may aid you. Some stranger coming to you like myself, -- some more eloquent stranger, -- may for the moment give your minds a turn in the right direction. But what is needed by you all,-- by all of us, by every man and woman that ever yet faced the world, -- is a daily renewed resolution to do the best with ourselves within our power. It is not that you and I do not know, but that knowing we fall away from our own purposes. The Latin poet Horace, who knew himself and human nature as well as any man who ever wrote, tells us this of himself: "I see the better way," he says," but yet I take the worse." My poor dear friend, -- the darling, -- who is spending all her life in reading novels, has, I am sure, said the same thing to herself a thousand times. You have said the same thing to yourselves. Who has not ? But what is the good of saying it if the lesson never really comes home to one? You can, all of you, educate yourselves highly enough if you will. The means are easily within your reach. It is not tuition which you require half as much as a purpose of your own to do that which you know, -- which you do really know, -- will be conducive to your own happiness. You also, no doubt, prepare your Hallams and your German dictionaries, or something that is equivalent to them. You have your own ideas of what you owe yourselves in the way of mental application. Are you satisfied that you pay yourselves that debt? If so, I do not think that you can be in a bad way [p. 87]

As I have now taken upon myself the office of censor of young ladies, -- begging that you will of course understand that I by no means suppose that there is any deficiency at ..................[sic], or that the emancipated darlings here are not all that they ought to be, -- I will venture to allude to one other matter which, according to my ideas, much concerns that higher education of which we are speaking. We all know the old stories, -- how our mothers, or, at any rate, our grandmothers, were very famous at the making of puddings and baking of pies; and how active they were about their houses, with their minds in their linen chests; and how they were dragons to the maids under them, so that everything about their houses was done in very ship-shape order. Well, we have changed that now, and are apt to tell ourselves that we have made the change in pursuit of that higher education of which we are speaking. Those old ladies who always had their minds in their linen chests or in the larder could not have done much with their books. So thinking, young ladies of the present day have exonerated themselves, or have become exonerated from much of the domestic toil endured by their ancestors.

But are they justified in exonerating themselves altogether? and if not justified in doing so, are they doing so without being justified? Is it the case, that while they are in the pursuit of higher education, -- or perhaps while they are reading novels and preparing themselves for the out-of-doors campaign of the afternoon, -- they are neglecting duties which, if they will only look the matter in the face, they will find to be manifestly incumbent on them? We all know that in every house there are such duties to be performed. Humanity, in its endeavours to shield women from those harder tasks by which man has to earn his bread and hers, has not intended that she should be idle. But when we look at our emancipated darlings we are driven sometimes to fear that they are, in their emancipation, taking altogether a wrong view of life. I have, at least, been more angry with that young friend of mine on this head than even on the score of her multitude of novels. [p. 88] Has she no idea, I have said to myself, that she should contribute something to the comfort of her father; something to the ease of her mother? Can it be that she thinks that life has no duties; that she thinks it is enough to read novels, and to put on a monstrous head gear, -- for in the last year or two she has descended to that, -- and to go to balls when there are balls to go to? Can not she even hem her own handkerchiefs or darn her own stockings? And I have thought of this -- till at last I have almost ceased to love that emancipated darling, and am glad, -- for the sake of certain young men whom I know, -- that she has not yet been settled.

I fear that, after all, I have said to you very little about higher education, and that I shall have disappointed alike the hopes of those who summoned me here and of those who have come to hear me. But I trust that I may have left on your minds some idea of the very homely truth on which I have desired to insist. In a few words, it is this, -- that that higher education which no doubt you all desire, though it may be assisted by the kindly work of others, can only be achieved by a steadfast adherence to fixed purposes made by yourselves on your own behalf.

1 Anthony Trollope, "On the Higher Education of Women" (1869), from Four Lectures, ed., introd. Morris L. Parrish. London: Constable, 1938.