Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Pallisers 2:3: The Splendors & Miseries of Courtesans · 29 September 07

Dear Harriet,

It’s been nearly a month since I last wrote a summary and filmic analysis of Part 2 (Volume 1) of the Palliser films. Life in the form of teaching (very arduous this term); going out with Caroline & Edward (Yvette is far away); other projects (the Jane Austen movies); and getting over one holiday and preparing for another (this coming weekend we go to Chicago) got in the way.

Also disasters: 3 car breakdowns, & my DVD of Volume 2, Parts 3 & 4 failed about 2 weeks ago and I had to order a brand net Set 1 of DVDs and wait until they arrived before I could begin again.

Patience has however won out, and in the meantime I studied other film adaptations of novel series (Jewel in the Crown, Love for Lydia), and decided that the 1974 BBC Pallisers as scripted by Simon Raven should be typed as an intermediate or analogous and critical adaptation of Trollope’s Palliser or (as they once were rightly called too) Parliamentary novels. Raven ranges across the 6 novels, reweaving parts of the them and characters and themes from other novels (The Small House of Allington, The Way We Live Now) into a new arrangement, redramatizing or dramatizing in the first place scenes left undramatized or told in letters (Anthony Trollope so often tells rather than shows), changing characters too in what they do, altering themes too, adding an important character from another book, and yet except in the cases of The Eustace Diamonds and The Duke’s Children holding to the original hinge-points, central character types, and crucial scenes and themes of the original books.

In this particular part (2:3) Raven conflates scenes, takes language that appears in one scene and divides it up into two, uses the French device of paired central figure and confidant, and makes Lady Monk (Helen Christie) as Burgo’s aunt take the place of Widow Greenow in Trollope’s novel so that instead of an acceptance and enjoyment of materialism that Trollope’s novel allows, this episode presents materialism and the performative calculating life as stifling, stacking the cards against those without inherited sources, and (even) vampirish. That the films are done in accurate enough historical costume makes them seem faithful too but actually enables the film-makers to turn the film into an ironic celebration of the English past.

I’ve also been reading about TV drama and mean to bring these studies into an assessment of the Palliser films and Jane Austen movies, but that’s for later on.

For today a summary and commentary with stills of Volume II, Part 3 of the Palliser films. In Part 3 Raven highlights the female characters and creates sometimes highly ambivalent sometimes sympathetic continuum of women characters: the female characters dominate this part and Raven shows us how different types of women dominate, cope with, or fail to survive adequately to their needs in a male-dominated world. He does not see society as male-dominated, but the viewer need not read against the grain too strongly to see that the women are at a strong disadvantage.

The strongest are so because their behavior is amoral, and Raven shows a real distaste for strong women in his three “floating” (the filmic Burgo Fitzgerald’s term) women; they are women who float above the demands of their society and manage to wrest them to their appetites and ego: the Countess of Midlothian (Fabia Drake), her side-kick in mischief, the Marchioness of Auld-Reekie (Sonia Dresdel), and Burgo Fitzgerald’s (Barry Justice) aunt, Euphemia, Lady Monk (Helen Christie). Ladies Auld-Reekie and Midlothian return to their roles as envious bullies who are determined to coerce everyone into giving themselves in marriage to uphold an establishment in which these two ladies are on top.

One of the most striking changes between Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her? and this film adaptation is that in Trollope’s novel Alice Vavasour jilts John Grey because she is seduced by the lure of vicarious ambition and long-range sexual adventure presented to her in Switzerland by her treacherous and ignorant cousin, Kate Vavasour and George Vavasour. In Part 3 of the Palliser films the idea is asserted 3 times (and dramatized in three separate scenes) that Alice (Caroline Mortimer) gave up Grey (Bernard Brown) because of what she experienced at Matching Priory at the hands of Lady Midlothian and what she saw of Glencora’s (Susan Hampshire) misery at having been driven “like a beast to a stud” when she married Plantagenet Palliser (Philip Latham).

In four French-like confidant scenes in the part (matched, juxtaposted & paralleled by scenes of Burgo Fitzgerald and George Vavosour [Gary Watson] confiding), Lady Glen urges Alice not to marry for position or wealth; not to obey behests of the heartless:

Lady Glen: “Alice don’t let them force you to take him [John Grey]. Even if your finger be put out for the ring at the altar, you should go back if you did not love him, believe me, Alice, believe me.”

Alice: “I believe you, Glencora.”

The urgent message is given a gothic background in a pivotal scene whose dramatic interchange and results (a cold) anticipates the conclusion of the series in Glencora’s death from pneumonia.

Before the young women go to the priory, Lady Glen defends their choice as not risky as there are no vampires out. The impliation is the vampires are all inside the brightly-lit houses.

In the penultimate and last episodes in the same ruin Mrs Finn (Madame Max that was) replaces Alice and insistently tries to persuade the Duke to allow his son and daughter to marry freely as Lady Glen wanted: only that way will they know real happiness. In this scene Lady Glencora tells Alice she would flee with Burgo were he to come to her.

Alice echoes Lady Glen’s words when at the close of the episode she tells George she has broken with Grey because of what “happened at Matching:”

Alice: “I learned that one must give one’s heart its freedom whlie there’s still time.”

Lady Glen’s experience as the result of cold tyranny is reinforced by Lady Midlothian in a scene in which the old woman manages to “distress” Alice intensely. Alice wins by holding out to her right to privacy against the old women’s insults and emotional blackmail: the Countess claims to have been Alice’s mother’s “dearest friend” even though she then proceeds to sneer with scorn at her friend’s choice of husband, Alice’s biological father.

The third worldly female vampire of Part 3, Lady Monk, Burgo’s aunt encourages, stages, and funds her nephew’s persistent pursuit of Lady Glen. Raven appears to detest Lady Monk as a high-class whore who enjoys sexual titillation (and perhaps more) from her relationship with her nephew; someone who is trying to wrest Lady Glen from Palliser for her nephew as a kind of lark and to get back at the two women, Ladies Midlothian and Auld-Reekie who broke her nephew’s engagement. Lady Monk is hypocritical, indifferent to her nephew’s real state of mind, half-crazed at times (the character is brilliantly acted by Justice); she’s an expensive useless doll covered with jewels she has done nothing to earn. Burgo is presented as a man still desperately in love with Lady Glen, but having crossed some rubicon where through alcoholism, a lack of serious work, and depression, he has become just about the worst choice a young woman innocent of money and without control of her property could make.

Burgo’s words more than once suggest he actually loathes his aunt; the last scene of 2:3 show her laughing sarcastically at the thought she will at last take Lady Glen from the Palliser group, while he cries through his faked laughter over his dependence on the corrupt whose luck and (shallow, phony) personalities have enabled them to “float” through life.

The lowest of the low in the Part is the female beggar & (probably) prostitute whom Burgo treats with more than exemplary kindness, giving her his last coin so she may have a bed and food. I have discussed this scene, presented a transcript and stills and remarked how Lady Glen reading Tennyson’s Maude poem is immediately juxtaposed to it to suggest to this Lady Glen could fall if she does not guard her sexuality from her society’s twisted mores.

While this presentation of the female characters is in line with Trollope’s, the partly nostalgic historicizing of the film’s story and characters is very much of the 1970s. It’s enormously revealing to compare the opening long drawn out scene of the part with Chapter 22, “Dandy and Flirt” in Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her?. Much of what’s said in Raven and his group’s film is taken from Ch 22, but the feel and meaning of the scene is utterly transformed because we must see what the two young women drive through and what we see are historical ruins and buildings built in previous centuries. In Trollope’s text because we are dependent on words, what emerges in our minds is the personalities of the two girls, their past histories and their psychological interaction; in the film because we must see visually concretely what happens, and the film-makers decide to exploit this what strikes us forcibly are the surroundings, how beautiful and rich and large are the grounds of the house, how ancient with history its origin in the Palliser family, in English religious and political history. The scene becomes part of the film’s engagement, romancing of, and idealizing pro-upper class questioning of 19th century history; the joy of the two girls is also prompted by their intense enjoyment of the gallop we experience.

(Johnson told Boswell life had few pleasures better than riding in a carriage on a somewhat windy day with a friend.)

The scene also anticipates 3:24 where we see Lady Glen as an older woman, established riding four-handed while here she says she would revel in the opportunity to do so. We are provided with a long tracking shot which follows the carriage through labyrinthine turns and paths.

These shots emphasize how big the property is, offering us, for example, a long shot of a ruined priory where the picturesque is linked to irrationality in Lady Glen’s story of how the property & power were first gained, & to nothingness in its emptiness and sense of history as vanished and the dead.

We enjoy many middle-shots of the beautiful season, with the young women feel we ride under an old fortress-like castle gate (militarism), and medium and close-up photos back and forth (triangulated close exchanges of dramatic dialogues) visualize of the growing friendship between Alice and Lady Glen.

The scene (taking a dialogic point of view as is common in novels and film adaptations) validates Lady Glen’s marriage to Plantagenet as allowing her place, privilege, luxury, beauty, wealth and doing what she enjoys most. The colors of the the landscape are a rich autumnal which Alice’s outfit (drawn like her others from Millais’s illustrations in other novels) matches.

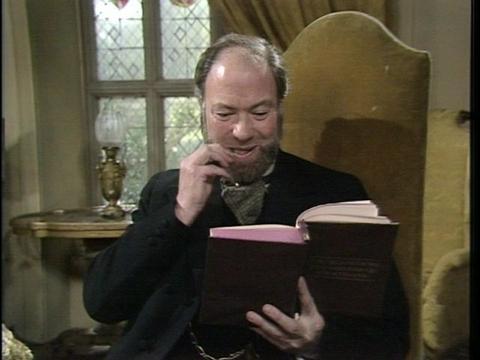

The Part (as is common in TV film dramas) uses many small visual symbols too. To me the most amusing was the use of a book said to be Balzac’s Splendours & Miseries of Courtesans, which in a previous episode Plantagenet Palliser disapproved of as reading matter for “his” wife. Balzac’s book keeps turning up like a bad penny: Mr Bott (John Stratton) reads it on the sly before his scene with Alice where he comes close to sexually harassing her as he pressures her to reveal Lady Glen’s confidences to him.

While Lady Midlothian is bullying Alice, Lady Glen finds she is sitting on it (hidden under a cushion by Mr Bott), and cannot think what to do but hold it visibly before her:

Lady Glen reads it up in her boudoir when she presents herself as ill, and scurries to hide it from Plantagenet whenever he enters.

Balzac’s book sums up the episode: we see the splendours and miseries of courtiers and courtesans, those who sell themselves willingly and make love to this employment, those who are coerced into it, and those who justify their position by within limited terms living an ethical life and trying to make ethical choices: this would include the Duke of St Bungay (Roger Livesey) whose pronouncements on the various characters, politics, and situations seem to me to articulate Trollope’s point of view, one quite different from Raven’s own.

Raven also adds an element to Trollope’s characterization of Plantagenet Palliser which becomes important in later episodes as a handle around which a section of a story may be built: Plantagenet Palliser shows himself to be incapable of changing his attitudes and apt to become more dense and stubborn when he is crossed. In two private scenes with Lady Glen in what is supposedly her private room, and before an assembled group of characters, he takes over the space, says what will happen in it (Alice will leave, he will be listened to and obeyed), and will not listen to Lady Glen’s reasonable objections. In particular in Part 3 Palliser will not hear her descriptions of her real emotions as “signifying.” He insists she go to Monkshade with him because he wants her there: it will be an embarrassment to him if she does not go and he needs to go there to network with Monk and all the people around him.

These scenes dramatize what will become a contining lack of compatibility as throughout the series the two people want to follow different values. But that Palliser will not even acknowledge she has a case makes Lady Glen desperate:

“he will not listen. Alice, I shall go mad with his man … man … he hears nothing. I speak to him. I explain. He just … he just doesn’t understand. Alice I don’t know what I’m going to do.”

She’s going to spend a lifetime manipulating behind his back to live as she deems a fulfilling way, only for the most part to be thwarted in the end by him when he finds out.

Raven continues to present Trollope’s George Vavasour far more sympathetically than Trollope (see 1:2: Raven’s George is a thus far well-meaning man at a decided disadvantage monetarily and in position, someone struggling for a decent career, and in love with Alice. Unlike Trollope’s Alice, Raven’s Alice responds to George sexually in a scene which images the displaced desires of Burgo and Lady Glen:

This is actually the first passionate kiss in the series. As with many of Shakespeare’s plays, sexual love is an accidental part of life in Raven’s Pallisers.

Now for a summary of the episodes within the part (as I have done before for 1:1, 1:1-2, and 1:2).

Episode 11: Alice Visits. The long carriage ride (referred to above) of Alice and Lady Glen through a lovely autumnal landscape and the splendid property of Matching Priory, a country house given them as a first present by the Duke for having married. A key speech by Lady Glen anticipates the joyous moment of Part 25 when we see her driving four with her two sons, Madame Max and daughter behind her:

Lady Glen. “I like driving more than anything else in the world I think. I ride sometimes but Mr. Palliser doesn’t like ladies to hunt. So that’s pretty tame. You know, Alice, I sometimes fancy I’d like to drive four-in-hand. I wonder what Mr Palliser’d say to that. Hmmm? Come on! [to the horses]”

When she asks Alice if Alice would like to drive, Alice demurs: “I’d much sooner you did.” Dialogue is epitomizing in films, and this shows a side of the filmic Alice that explains her deep-seated choice of John Grey, presented in these films as a kindly open-minded protective man; in her scene with George (Episode 14 below) Raven’s Alice becomes quiescent to George’s advances seems distressed at how her father and grandfather will take her engagement. She is a woman who does turn to men for support.

Alice is greeted by Mr Palliser warmly, and meets (as do we for the first time), the Duke of St Bungay whose importance is signalled by conversation which shows how quickly a friendship between him and Lady Glen has formed.

Lady Glen snubs Mr Bott, and the Duke is amused.

There follows the first confidant scene between Alice and Lady Glen in Lady Glen’s beautiful boudoir room, one rich with history in the Jacobean ceiling and old church-like windows. It’s in this scene that Raven’s script and Hampshire’s acting brings Lady Glen before us as a spontaneous genuinely feelingful woman, not performative, by instinct though wanting power, sensual satisfaction, & adventure, not thoughtful, not careful in the way of Alice. The scene is juxtaposed to one of Burgo and George playing backgammon; they discuss George’s correspondence with Alice from which he says he learns nothing to Burgo’s purpose about Lady Glen.

A third confidant scene, ugly with seething envy and manipulation between the Ladies Midlothian and Auld-Reekie.

Lady Midlothian to Lady Auld-Reekie: “If there is one woman alive who Glencora hates more than me, Charlotte, it is you [tone of delight in the thought]. She will never suffer both of us in the house.”

Of interest is how the camera moves from Alice’s tight face refusing to speak of Burgo in London to Lady Glen, to George and Burgo’s faces over their game (“Dealers’ last?”), to Burgo’s hands playing with the dice to the two old women’s bejewelled hands.

Episode 12: Entertaining. Alice in the vestibule before entering the Palliser salon. She looks at her dress, stiffens herself, puts her hands in front, holds her head a little higher, hesitates before the door:

We watch a long scene of politicking where we see Mr Bott left out, and how Barrington Erle (Moray Watson) functions as a mouthpiece for the average point of view (complicit, approving) of what is seen to happen. Then a second confidant scene between Alice and Lady Glen (quoted from above), juxtaposed to another of Burgo and George, now at billiards, where we see George somewhat generously willing to fund Burgo (it’s not clear that Burgo will be able to do anything for him if he runs away with Lady Glen), although it seems George must borrow from Jewish ursurers for any funds.

(The 1995 P&P also placed the heroes in fencing and billiard scenes; here the billiards seem to stand for women.)

This 12th episode culminates in the moving street scene between Burgo and the female beggar. It’s clear these two men are not responsible for the power arrangements of their world—one flaw in the series is that no one seems to be, and for the feminist, the worst agents of destruction are not simply older people, but women and highly sexualized sadistic men (for example, later, Ferdinand Lopez as played by the feline yet macho Stuart Wilson) Raven thinks all women long for.

Episode 13. Meddling Again. Lady Glen reading in her boudoir with Alice some of the most highly sexualized lines in all Tennyson, lines which evoke mirth from the two young women:

“There’s fallen a splendid tear

From the passion flower at the gate.

She’s coming my love, my dear … ” &c&c

Palliser comes in and (naively) rejoices at what he perceives as innocent laughter; he is also glad to see his wife cheerful: “That’s very pleasant, my dear, very pleasant indeed.”

The next scene that ensues, though, is not pleasant: he insists they go to Monkshade and, despite his asseverations to the contrary, is well aware that his wife’s previous engagement to Burgo “signifies: when he replies to her

Lady Glen. “Let us stay here, Plantagenet.”

Palliser. “Yes, I feared lest you might say that.”

Juxtaposed to this scene is a still of Mr Bott salaciously enjoying Splendors and Miseries of Courtesans, preparatory to his insinuating nagging of Alice as (in his mind) no less a prostitute than himself.

Then the direct (and yes nagging) challenge of Lady Midlothian to Alice, Alice’s second distress before Mr Palliser (she is disturbed far more by Lady M than Mr Bott), Palliser’s stern disapproval of the plan to go to the Priory and seething refusal to “forbid it.”

The 13th episode climaxes in a new pair of confidants: Burgo and Lady Monk plotting against Lady Glen. Lady Monk is dressed in the same dark emerald shade of green as Lady Midlothian. As Burgo lays back on a couch dreaming of how Lady Glen “will melt under his hands” (to use his phrase from the last scene of 1:2), we hear a hollow night-time ringing of priory bells, and the scene dissolves into

Episode 14 called Lady Glencora’s Illness to emphasize that one of Lady Glen’s aims in going into the priory was to become too sick to go to Monkshade. There’s a strong part of Lady Glen’s mind which tells her she must not melt before Burgo. She throws off her gauzy cape, and when Alice asks

Alice. “Glencora, what are you doing? You’ll catch cold.”

Lady Glen. “I know and I mean to catch cold. That way I can hide myself away and escape what can happen.”

The next morning Alice bravely tells an angry Mr Palliser he must not take Lady Glen to Monkshade.

Departing from Trollope’s text, Palliser retorts by asking Alice to leave the house (shades of General Tilney in Northanger Abbey). Thus in the next scene he can inform Lady Glen her confidant is gone, she is to get better and come down from her room, and go with him as this is her “duty” as his wife (Lady Midlothian used the word “duty” to Alice). A powerful set-to between the two of them ensues, fierce face to fierce face. He is now determined his will shall “overcome” hers.

Lady Glen. “You don’t need me. As you said yourself, it is all politicians.”

Palliser. “Your absence will occasion comment. Now that is the end of this discussion. [Goes over to door and opens it.] Now you must rest.”

As he slams the door going out, we see her run to one of the windows that recurs and is a dominant motif as a beautiful caging in the series from 2:1 to the 26th part:

The next scene we again see Alice’s father (most unlike Trollope’s Mr Palliser; see 1:2) waiting up for his daughter, affectionate, caring, and distressed over her breakup with John Grey. It is again made clear her decision was motivated by what Alice saw at Matching Priory.

Now a brief glance at Burgo and George at the club framed by a dialogue between the choral figure of Barrington Erle and Dolly Longestaffe (Donald Pickering). Dolly is begining to think George is “not sound” because he is spending too much time with Burgo Fitzgerald and “trying to raise money on Vavasour Hall” while “his grandfather’s still alive and kicking and the place ain’t even entailed to him.” Thus the world’s morality speaks. George’s assumed “money” is “fishy.” But Erle is not bothered: “Well it’s the sort of thing we’re [the party’s] always getting whether we like it or not.” And after all, what matter if he gets in or out as far as they’re really concerned.

The penultimate episode concludes with George’s visit to Alice. It’s utterly different from Trollope’s presentation where Alice has no sexual desire for George whatsover and he is willing to take her money in her stead. They look longingly at one another, kiss, and she is mastered by him as well as anxious about how her father and grandfather will take the news. She laughs at the notion she is now her “own mistress,” and although self-possession returns when she offers her money now to George (rejected by George until they marry), her mind recurs to Lady Glen’s position and it’s clear she has accepted George because Lady Glen’s caged life has become a symbol of the caged life she is risking with John Grey.

Episode 15. New Engagement. Another snowscape: the series has had several: it’s as if the film-makers see this void whiteness as a needed rest from humankind. It’s also the outside of Vavasour Hall into which the camera goes to allow us to see a passionate family scene where Alice tells her grandfather (Donald Eccles) she’s broken with John Grey, and is engaged to George, his grandson; her father becomes livid with worry and his description of George is phrased so to the ears of the viewer it is also a description of Burgo:

“I think he is as unsafe a man as I ever knew to be entrusted with the happiness of a young woman, and that is all …”

Alice maintains George has changed, Kate (Karin MacCarthy) says her uncle has been “too hard” on George, and when the grandfather speaks ferociously and utterly indifferently about George (again unlike Trollope’s novel, refusing to allow George to visit) because the grandfather fears George will spend all the property to feed his ambitions, we tend not to blame George. We remember Mr Scruby and Mr Grimes from 1:2. We have only seen George with his sister and Alice & as a figure in a male landscape whose normative figures are Longestaffe and Erle.

The part comes to a close at Monkshade where amid the company Lady Monk and Burgo await Lady Glen. After all, Palliser left her behind: his face is grim as (supported by the “faithful” Mr. Bott), he tells what he knows to be part lies: she was too ill. Burgo manages to behave civilly in response to Palliser’s offer of a handshake:

but then hurries out in what is visibly a state of sorrow an distress which all ignore.

Before the concluding shot of Burgo and Lady Monk replotting against Lady Glen’s peace (for that’s what it is), we get framing dialogues between the Duke of St. Bungay and Erle where Bungay characterizes Burgo as “reckless” & “rotten” and Lady Glen as the “sweetest girl that ever was” where sweetness appears to mean more than innocent and good, but socially “genial,” to Bungay’s taste, and Erle asks, “Yes, but does Palliser appreciate such sweetness, do you think?”

A close-shot of a nervous-looking Palliser suggests that’s not what is the issue; the issue is his male pride and her safety (we might put it autonomy).

It is indicative of Raven’s dark pessimism that so many of the Palliser episodes end on ironic, hard, or grief-striken scenes.

For me in this episode Alice emerges as a brave young woman, her gravity the outward sign (and paralleling Palliser’s) of her threatened integrity.

A typical expression on Alice (Caroline Mortimer)’s face as she dines surrounded by her grandfather, father, and cousin

Elinor

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Elissa on Janeites:

“First, thank you Ellen for your creative and artful analysis of the Trollope “Palliser” novels filmic adaptation that appears in your blog. It has made me realize, yet again, just how much I adore both Trollope’s novels and that particular Simon Raven production adaptation. Reading your insightful article [actually, you present it with select stills from the video that really present the material as “filmic criticism” —thus, I believe you’ve created an entirely new genre!], has distilled for me just what the term “a faithful adaptation” may mean.

But what you write of the great Trollope panarama of political novels has much to inform us about Austen’s novels and their film adaptations—a subject that has been much written about over the past two weeks. This concerns, I think, the definition of what constitutes a “successful” film adaptation of a work of fiction: literal faithfulness of words, or perhaps faithfulness of scenic adaptation/atmosphere/mood, or perchance faithfulness to the original author’s spirit and intent. Obviously, from my previous recommendation of this wonderful series, I think its creators have captured the essence of TRollope’s world. Viewed from this set of criteria, I fear, most of the film adaptations of Austen’s books, really do miss the mark [no pun to P&P0 “archery scene” intended].

Certainly, when considering the original televised “Palliser” series, we must consider first and foremost, its splendid cast. Really, each role is wonderfully acted, but several are so extraordinary that they truly lift this serial production to magical realms: Of course, first and central are the two leads, at first glance so different, yet ultimately so romantically right for each other—Susan Hampshire as the beautiful, impish, and divine Lady Glencora who grows into wisdom and political prowess and Philip Latham as the stern, intellectual, and doting Plantagenet Palliser who adores her. The chemistry between these two is extraordinary. Certainly no such chemistry exists between any actress yet who has played Elizabeth Bennet and any actor playing Darcy. And then there is the WONDERFUL Roger Livesey as the urbane, witty, charming, and politically astute Duke of St. Bungay, Donald Pickering as the effete snobbish clubman Dolly Longstaffe, Donal McCann as the impoverished, handsome revolutionary member from Ireland [Trollope’s “Che”] who captures the heart of every lady he encounters. We even have Derek Jacobi as the absurd Lord Faun, ordered by his ferocious mum to propose to anyone in skirts who has some funds—now here is our mid-Victorian version of Lady Catherine! I truly feel that it is the chemistry and magical acting of these wonderful players [indeed, the dyslexic Dame Hampshire has said that often lines were improvised on the set] that have created such a masterpiece—and ONE THAT, EVEN IF LITERALLY NOT FAITHFUL TO ALL THE WORDS/SCENES OF THE NOVELS, IS IN SPIRIT A FAITHFUL RECREATION OF THE WORLD ITS AUTHOR INTENDED.

Other examples of filmed productions that have successfully achieved this translation from prose to film are mentioned by Ellen, and I agree: Brideshead Revisited and The Jewel in the Crown do this as well. An example of a BBC production on Masterpiece Theatre that failed woefully at this novel-to-film translation, in my opinion, was the most recent attempt to serialize Middlemarch—a true abomination.

With the many Austen novel filmed adaptations, we have a varying degree of success, but there is none as yet, I think, that comes close to achieving the spirit of any of JA’s wonderful works—no matter how compelling the scenery, how majectic the palatial interiors. Thus, for me, Emma Thompson’s S & S with charming countryside, nice interiors, and 5 wonderful actresses comes close [both Emma T. as Elinor and Kate Winslet as Marianne {of course Alan Rickman as Col. Brandon} and then the great portrayals of Mrs. Jennings, Lucy Steele, and even cruel sister-in-law Fanny]. I also do think the Gwyneth Paltrow Emma conveys much of the spirit of the novel. And by the same criteria, although both leads Greer Garson and Olivier were terribly miscast and certainly had no spark between them; the scenery was often absurd and the costuming even worse, in P&P0, we have such wonderful performances by the supporting characters—both Mr. and Mrs. Bennet, Lady Catherine, poor Mr. Collins, oily, caddish Wickham, and haute snobbish Caroline Bingley—that for me, they carry the film. They carry it right into the sphere that Austen intended as far as I’m concerned. And that, I think, is why Arnie responded to it rather positively in a recent posting.

There is much more to say on this interesting topic. But I beg indulgence for having held the stage so long, and bid you all a very good night.

Elissa”

— Elinor Sep 30, 6:32am # - Dear Elissa,

It feels curmudgeonly and ungrateful to protest against such lovely praise, but I must do on one point: my analysis does not praise the Palliser films for being faithful. I say in fact they are of the analogous or critical type of adaptation: not close, but somewhat loose, changing the original books in many ways.

I praise the movie as a work of art in its own right and use fidelity standards in order to understand what’s there. I compare the original books to the films and that helps me to understand what Raven and his team has produced and how the films relates to Trollope’s books. But this is process and not the point of what I wrote. What I wrote was to show how the films have their own themes, their own patterns, have recreated the character differently and produced a very different kind of statement.

This is important for the Jane Austen movies all right. I mean to praise a number of them (many) as works of art in their own right and use fidelity criteria to understand them. I do not evaluate them by how faithful they are since over half do not mean to be faithful in the literal way and the 10 seeming faithful ones are valuable not because they are faithful but as filmic art in their own right.

Here (among other places) is what Elissa ignored in my blog:

On the blog I wrote:

“One of the most striking changes between Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her? and this film adaptation is that in Trollope’s novel Alice Vavasour jilts John Grey because she is seduced by the lure of vicarious ambition and long-range sexual adventure presented to her in Switzerland by her treacherous and ignorant cousin, Kate Vavasour and George Vavasour. In Part 3 of the Palliser films the idea is asserted 3 times (and dramatized in three separate scenes) that Alice (Caroline Mortimer) gave up Grey (Bernard Brown) because of what she experienced at Matching Priory at the hands of Lady Midlothian and what she saw of Glencora’s (Susan Hampshire) misery at having been driven “like a beast to a stud” when she married Plantagenet Palliser (Philip Latham). ”

I like this; it makes Alice’s refusal of Grey not just a foolish girl’s longing for a sexy suitor, but a woman who has looked at her friend’s coerced marriage and said nay.

On the blog I wrote:

“the partly nostalgic historicizing of the film’s story and characters is very much of the 1970s. It’s enormously revealing to compare the opening long drawn out scene of the part with Chapter 22, “Dandy and Flirt” in Trollope’s Can You Forgive Her?. Much of what’s said in Raven and his group’s film is taken from Ch 22, but the feel and meaning of the scene is utterly transformed because we must see what the two young women drive through and what we see are historical ruins and buildings built in previous centuries. In Trollope’s text because we are dependent on words, what emerges in our minds is the personalities of the two girls, their past histories and their psychological interaction; in the film because we must see visually concretely what happens, and the film-makers decide to exploit this what strikes us forcibly are the surroundings, how beautiful and rich and large are the grounds of the house, how ancient with history its origin in the Palliser family, in English religious and political history. The scene becomes part of the film’s engagement, romancing of, and idealizing pro-upper class questioning of 19th century history; the joy of the two girls is also prompted by their intense enjoyment of the gallop we experience.”

I hope this speaks for itself.

ON the blog I pointed out how Mr Vavasour’s character is utterly changed, George is made pleasant and moral, and a vampirish woman, Lady Monk, substituted for Widow Greenow (Trollope’s complacent materialist).

So, Elissa, while I can’t thank you enough for pointing out some of the details of my filmic analysis and agree the film is marvelous, I did not at all say it’s marvelous because it’s faithful. I said it was only loosely faithful. I said it may give the impression of fidelity (and gave reasons, which include the costumes and historical background and literal events). I used fidelity criteria to understand it not praise it.

I am puzzled why people insist on praising a movie for something it is not and cannot be, for criticizing movies for being something they are not and cannot be. Fidelity as a standard gets us nowhere in understanding what these movies are. Fidelity as a basis of comparison is very helpful.

E.M.

— Elinor Sep 30, 6:43am # - From Elissa,

“Ah Ellen—I didn’t make myself clear about the “Palliser” film episodic series: I agree with you completely that the filmic series was not completely “faithful” to the books. But I do feel that the director/film writer did manage to convey the essence of all the novels nonetheless, and in that sense, the films are “faithful” to the books. Perhaps this is analogous to the ability of an impressionistic painting by Monet or van Gogh to effectively recreate a scene and place us in it just as validly and splendidly as a more representational painter.

Another of your main points is also very important, and I thoroughly agree with you as well: many, perhaps most, film directors start with a specific point of view, even a philosophical or political agenda or perhaps just a money-making agenda, then cast and create their characters, who, often merely because of the particular actor’s stance/personality/appearance, then take on a wholly new, idiosyncratic life of their own. Two cases in point that annoy me no end: the two principals who play Lynley and Sargent Barbara Havers on the current bbc serialization of the Elizabeth George [wonderful books] series; Jennifer Ehle as Lizzie [no, no, never]; these are all talented actors, but they simply cannot and do not convey any sense of the characters who live in our imaginations from these novels. I am even tempted to add Olivier himself to this list; perhaps the world’s greatest actor, but I do not feel he successfully portrays any real sense of Darcy; whereas Edna May Oliver in her absurd pseudo post- US-Civil War costume and Melville Cooper [virtually an unknown] convey a sense of Lady Catherine [even with a bit of plot flip-flop] and Mr. Collins perfectly.

Again, I apologize for the length of my responses. During the past two days of the Jewish festival of Succot as I sat in a fragrantly decorated, fruit-perfumed temporary house with roof partially open to the nighttime stars, followed by the Sabbath when I could not write, many of these thoughts whirled about. And Mr. Woodhouse was completely wrong: the nightime air, gentle breezes, and sense of the vast firmament above us are not at all dangerous—they open us up to both the world and the vastness of eternity!

Elissa”

— Elinor Oct 1, 7:37am # - Thank you again Elissa for the clarification. Your emails are not too long at all: they are thoroughly thought out and beautifully written, a joy to read and to respond to.

To be stubborn though I feel you still don’t move away from the criteria of fidelity as a way of judging a film adaptation of a book. In the case of not-such high status books this mostly doesn’t happen (some huge percentage of movies are adaptations of books), but in the case of high status books or cult figure’s books it does, partly identity politics, partly a way of bringing down the product and keeping the text an unexamined fetish. Not that you did that at all, but I’m speaking generally of some of the sources of this kind of insistence.

My idea is to move away from fidelity as a standard or criteria for judgement, and use the book comparatively: it becomes a way in to understanding the film-makers and film in its own right. After working on terminology for types of adaptation, now I’m trying to work on terms which will enable me to compare films closely. It’s not easy. People say that books give us so much more information than movies; not really. They give us a different type of information. Think of how a typical mise-en-scene is so chock-a-block with visual details which cannot begin to be put in a book and these are carefully put there by the film-makers.

What I'd like to do is write something useful which can move people away from the subjective idiosyncratic kinds of movie criticism that produce no consensus because they are not based on anything all can agree on.

E.M.

— Elinor Oct 1, 7:47am #

commenting closed for this article