Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Alan Plater's _Barchester Chronicles_ · 20 December 07

Dear Marianne,

I have now watched the 1982 BBC film adaptation of Anthony Trollope’s The Warden and Barchester Towers four times: Barchester Chronicles, screenplay Alan Plater, directed by David Giles, produced by Jonathan Powell. I liked it more each time I saw it, and it’s about time I made a stab at trying to say why. Most commentary on it comes from a general impression, and I’ve all too often come across the denigrating statement, the mini-seris is Cliff Notes in movie form. Untrue.

Barchester Chronicles falls into the type of adaptation I call “faithful”: it contains all the original hinge-points (general story line, crucial events presented more or less in the same way, famous lines kept, and central characters); it alters as well as expands on the work’s original themes in a contemporary way which reflects the creative interests of the film-makers (director and screenplay writer) and resembles other works of its producer (and company). By contrast, the Palliser films is an analogous adaptation: it departs from the original books by altering central hinge-points; changing the enunciation (the way a scene is presented); changing emphases completely so different characters become important and are introduced in different ways from where Trollope does; and highlighting new themes at variance from the original.

It’s a toss-up whether the deep pleasure of this mini-series comes from Donald Pleasence’s acting performance and domination of the films as Mr Harding or Alan Plater’s genius which provides this inimitable part.

Septimus (Donald Pleasence) and Eleanor (Janet Maw) distressed at the news John Bold (David Gwilliam) has brought a lawsuit against him

Plater’s genius: his screenplay is a marvel of suggestive and epitomizing bon mots and dialogues; his scenes combine a sense of the poignancy and loneliness of human existence from a distancing comic standpoint which softens the pain; he impugns ruthless contemporary mores on behalf of advancement and power and fulfilling one’s appetites (whatever they are) in the person of a character who suffers the most and (paradoxically) and is expelled at the end: Obadiah Slope (played brilliantly by a young Alan Rickman) is the Malvolio of this middle class feast of cakes and ales.

Plater has filled out the portrait of Mr Harding, probably the least altered of Trollope’s character, impeccably done by Donald Pleasence—he also played Malachi in an earlier film adaptation of a relatively unknown gem of a story by Trollope; the reappearance of this actor results from his belonging to a set of actors often called upon to do these TV film adaptations, and the reality that underlying Trollope’s portraits of truly ethical older man is the same archetype. The character’s refusal to be coopted into using other people for advancement is comically emphasized and undercut by the sputtering incomprehension of Archbiship Grantly (inimitably performed by Nigel Hawthorne). Pleasence conveys gravitas too, a seriousness of emotion and integrityand awareness of the corruption of the world (he understands Madame Neroni fully with no effort) consonant with Trollope’s original conception.

Mr Harding’s refusal to be complicit in any kind of cruelty or injustice if he can help it (and he can help it) is contrasted to Plater’s conception of Mr Slope not as a vulgar upstart, comically ludicrous and appetitive, a fundamentalist in religion (Trollope’s particular bete noire), but a man out for advancement who does not understand himself very well and has not hope of entering and coming to power over the cliques he is outside of so finds himself endlessly going back and forth on decisions to his own detriment. Rickman is not so much the “opposite” of Mr Harding as someone living in another world of intense vacillation and confusion, an almost surreally driven man.

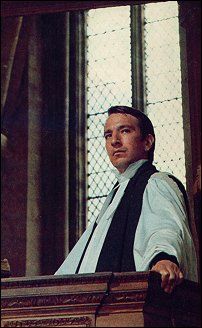

Obadiah Slope (Alan Rickman) in the pulpit

Plater has little interest in the money matters of church politics, the changeover from a land-based agricultural community to one which is a suburb to a capitalist industrial state, the economic injustice to the pensioners, and all but the most minimal references to these matters is cut. Only enough is left to keep the original plot-design. What he is interested in is Mr Harding is genuinely religious, and no one else is, not so much to expose the church as a place of supine sinecures, but rather simply as a simulacrum of the business marketplace world his viewers have to find their livings in. The scene where he tells Sir Abraham Haphazard (Michael Aldridge) is not about him refusing to manipulate the law, but a contrast between an otherworldly ethical man and a busy master networker. When Mr and Mrs Quiverful (Jonathan Adams and Maggie Jones) discuss how Mr Quiverful has been cheated of a place before, how Slope is pressuring, and she determines to apply to Mrs Proudie, the film becomes just what Elaine Showalter argues in her Faculty Towers: the first satire of an academic (and also any court and many business & corporate) milieus.

Here’s a comical rendition of someone’s determination to overcome all machination and obstacles: Mrs Quiverful marching over to Mrs Proudie (Geraldine McEwan) to demand she maintain the offer she clearly meant to give Mr Quiverful:

John Bold (David Gwilliam) is mocked (as in Trollope) as a naive idealist, but he and Tom Towers (George Costigan) on the one hand, and attorney Finny (John Ringham) are kept separate from the corruption in the church story. Their attack is not seen as undermining the church so much as in Bold’s case simply a pity for poor people who can’t get medical care.

Mary (Barbara Flynn) and John Bold (David Gwilliam) in the apothecary shop part of their house

The series if careful not to do anything which could be seen as seriously critiquing any religious beliefs or practices or the cult groups which emerge from fundamental hierarchies of society (the latter is one of Trollope’s targets).

The center of the six episodes is the loving relationship between Mr Harding and Eleanor Bold (Janet Mawe); Trollope’s Barchester Towers alters Mr Harding’s position vis-a-vis its story and Eleanor so he becomes a secondary figure in her life and Francis Arabin (Derek New) remains a minor character; we hardly get to know him at all, even if he triumphs over his two rivals, Slope and Bertie Stanhope (Peter Blythe) when it comes to marrying Eleanor. He is not made a cynosure for us to see an ideal gentleman emerge (in the way that Raven follows Trollope for Plantagenet Palliser). Four of the six films end with Mr Harding and Eleanor in close supportive relationship (they say they will travel through life together), and the prefatory and closing illustrations show them as the pair at their center. They are given the most heart-felt sensitive and empathetic lines to speak to one another throughout. The scenes are arranged to bring them out as the abiding couple whose values hold them together. (In “Malachi’s Cove Malachi’s relationship with his daughter functions similarly.)

Septimus (David Pleasence) and Eleanor Harding (Janet Maw) bidding adieu to his position as Warden

The male characters in the series swirl around Mr Harding and Eleanor in the first half and again in the second, with the Grantlys the first alternative symbolic center (Parts 1 & 2); to which are added the Stanhope household and the Proudies (Parts 3-6). The Proudies are in conflict over who is to rule the diocese, and when Mr Slope loses out to Mrs Proudie (played as a seething sexually frigid woman), this is a parallel to what happens in the love and property stories: the woman are the powerful people, the deciders, the humiliators, the party-givers. When Mr Quiverful succumbs to Slope’s pressure and gives up the offered position, Mrs Quiverful becomes a proactive successful negotiator through stubborn crying. Madame Neroni (Susan Hampshire, somewhat miscast) is a slithering spider-lady who brings men into her lair.

Madame Neroni (Susan Hampshire) as cynosure

The men (all except Bertie Stanhope) may have property and money, but the series dramatizes the idea women’s sexual power is real, not contingent, permanent (not fleeting and gone when they age) basically by presenting emasculated males. Susan Hampshire was most creditable when it came to projecting a sly sexuality, controlling and humiliating Slope, and expressing a proto-feminist point of view. Hampshire’s Neroni’s parallel is Mrs Grantly, played by Angela Pleasence as a feline, sexually gratified and gratifying wife.

Mrs Grantly (Angela Pleasence) and Mrs Stanhope (Phyllida Law) acting as choral commentary

Hampshire is much less successful as a sybil in a lair to whom all comes, and who dispenses cynical but accurate wisdom to all, especially in her scene with Eleanor Bold.

Small pleasures for me included Barbara Flynn as a matter-of-fact and kindly best friend to Eleanor Bold throughout the series; Ursula Howes as Miss Thorne, a similarly protective sister of her brother, Wilford (Richard Leech). Plater manages to get in much of Trollope’s absurdist dialogue (e.g., the bodily search of nuns for Jesuitical symbols as the aim of one bill), much of the farce (when Mrs Proudie’s dress is torn and she says “Unhand me,” with an electrified Slope standing by, Bertie [Peter Blythe, aptly named] all courtesy). Sweet comedy comes from Cyril Luckham as Bishop Grantley, unable to understand economics, but hoping to make all love one another. A helpless presence. As I say, the women in this mini-series emerge as central powerful effective presences. The only man who attempts to stand out against and manipulate them, Alan Rickman, fails, but then he is ejected, not subject to them, and perhaps that is why in our masculinist culture he is remembered and celebrated as the effective presence in the films.

To conclude, I like the ethical values Donald Pleasance is made to be a celebration of. Mr Harding is not a figure who lays bare the power structure of his community (as in Trollope). Mr Harding is more like the figures in Trollope’s novels who simply turn away (Mary, Lady Mason in Orley Farm, Lily Dale in The Small House at Allington). I love his distaste for publicity at any price: ”“If I am to be ruined, I would much rather be ruined quietly.” I love how his nervousness becomes an index of someone who simply cannot bear to listen to stupid cruel talk: his imaginary violin playing is signals his unworldliness but also is psychological and social: he is refusing to allow his soul to be touched by, his mind to be have sunk into it some peculiarly egregious hypocrisy as truth.

One of the opening drawings (paratexts) to the series

Elinor (Dashwood)

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- I wrote earlier about the 1974 Penrich Malachi’s Cove, directed and written by Henry Herbert, an adaptation of one of Trollope’s finest stories. This adaptation is a successful translation of the original powerful story of a desperately poor and socially isolated young girl, Mally (played by Veronica Quilligan) who makes a meagre living for herself and her grandfather, Malachi, in this film, a badly crippled sick alcoholic but still sane and well-meaning old man (played very effectively by Donald Pleasence, also Mr Harding in the later Barchester Chronicles).

The use of landscape was cinematic and expressive. Herbert did justice to Trollope’s usual ambivalent way of showing how socially dangerous and psychologically deleterious and self-destructive is a partly self-imposed exile (Mally is also made an outcast because her poverty leads many in her community openly to scorn her). At the same time Herbert Mally was also an elfin creature of a fantasy-wild, Pleasance a greedy and dependent if loving gnome. (A still of Veronica Quilligan as Mally on the wild cliff

My only adverse criticism of the film is that unlike Trollope, Herbert chose to present as a dense stupid unforgiving harridan only the mother of Bart, the boy whom Mally had vowed to prevent picking seaweed with her (to sell as manure) and instead saved. In Trollope both the boys’ parents destruct Mally and would have accused her of murder had not Bart lived. Thus an anti-feminist note is struck not in the original.

Herbert also had the grandfather at great risk to himself perform the impossible feat of climbing down the rocks to hold onto the boy while Mally was gone for help. This made the grandfather seem not an irresponsible leech, but rather a desperate father-hero to his granddaughter. It deepened the girl-grandfather pair. They exist together near the rushing waters which drowned Mally’s mother and father.

Herbert’s camera also recreated and dwelt on the drowning of Mally’s parents (which she witnessed and has bad dreams about) and their grave (which she visits), making a theme of the film how to the poor living close to nature there’s a fragile thin line between life and death.

E.M.

— Elinor Dec 20, 3:24pm # - I’ve now discovered Plater has had quite a distinguished career in

radio plays, plays for the stage and one-off (single, not mini-series) adaptations.

He wrote at least one of the screenplays for a series I’ve described here (Shades of Darkness, and which has been much admired. He has been the recipient of a number of distinguished prizes—though of recent not for TV (Andrew Davies seems to have that wrapped up).

See http://www.us.imdb.com/name/nm0686786/

E.M.

— Elinor Dec 20, 3:32pm # - From Kathy C:

“Dear Ellen,

Your analysis of the Barchester Chronicles is thorough and enjoyable. You’ve researched for a long time, I know.

Kathy”

— Elinor Dec 22, 8:44am # - I realize that I have not made any explicit connections between the Trollope matter used in Barchester Chronicles and the Trollope matter used in Raven’s The Pallisers.

So let me bring forward this paragraph in my analysis of Raven’s Pallisers, 3:5 (“The Back Story is about Male Outcasts”):

"It seems from this film that in order to be decent you must cut yourself off from the corrupt order (as Burgo does when he finally gives up his pursuit of Lady Glen as it is becoming harassment), but if you do & you have not the wherewithal to retrieve your decision (money, as Plantagenet has), you suffer for the rest of your life. That line or half-line is uttered in the series."

Raven's depiction of the problem of decent males in contemporary society coheres with Trollope's presentation of Mr Harding as an exemplarily ethical man, but Trollope does not radically impugn the social order and Alan Plater keeps the risk Mr Harding runs to a minimum as he seems never in danger of homelessness and its consequences in the films (nor does Eleanor who is dressed as imperturably comfortably as everyone else in the films).

E.M.

— Elinor Dec 22, 1:33pm # - I also did not go into filmic techniques. Alas, the film is not interesting in this important way.

Barchester Chronicles remains basically a televisual drawing-room comedy. There is no voice-over; no epistolarity; close-ups are not made fundamental, nor are we invited to see much through the camera we can never see in life; no landscapes except through picturesque drawings before and after each part and what is needed for the fete champetre at Ullathorne. My feeling is when viewers accuse the series of being sheerly “Cliff Notes,” they are attempting to put in words the ennui they feel watching this quiet dramatic narrative presentation. It does not do against modern sophisticated techniques; there are also no charismatically sexy and famous stars.

The language used to express a lack of filmic excitement does not come close to what is the problem; I have often found in classrooms and elsewhere people attempting to express an idea by uttering cliches which have not much to do with the idea but can be attached to the subject matter in question.

E.M.

— Elinor Dec 22, 1:40pm #

commenting closed for this article