Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

_The Pallisers_, 4:7: The Beginner (Phineas Finn) (2) · 28 January 08

Dear Harriet,

Yesterday I sent along a brief thematic essay on Pallisers 4:7, “The Beginner;” today I want to add to that, another concise summary of the individual episodes, with brief commentary and stills.

Volume 4, Part 7. Episode 31: “More Entertaining.” Scene 1) Phineas Finn walking in the rain; he can’t afford to ride, but at the last moment takes a carriage for sixpence so he should look like he came in style. His poor and lowly origins stressed in a way not in Trollope. Trollope wants us to see the egregious luck of his rise; Raven that he comes from below and should not lose his allegiance. Trollope does not see Phineas (Donal McCann) as that low nor any such class allegiances. ; Scene 2) a long involved many conversation scene where we see Lady Glencora (Susan Hampshire) and Plangenet Palliser ([Philip Latham] he reluctantly) hosting their first party for the “right” people (powerful or people who powerful people have requested be invited, e.g., Madame Max [Barbara Murray]): here we remeet and meet a number of politicians who are going to matter in Phineas’ story (e.g., Fitzgibbon [Neil Stacey], Monk [Bryan Pringle]). The conversations highlight issues to come. Lady Glen is not kind to Finn when she spontaneously imitates his attempt to clean his shoes in the hall; Monkey sees, monkey does.

Lady Glencora Palliser (Susan Hampshire) mocking Phineas Finn (Donal McCann) (Pallisers) (BBC 1974)

Lady Glen doesn’t stop to think how unkind this is; she reacts because he looks funny to her, unaware that he will be (slightly) embarrassed to be exposed in this way. Then she doesn’t think when she makes her pun about how “mud” sticks as she cleans his face. She looks puzzled at his discomfort. It’s such people who do run parties; it takes unawareness to enjoy this kind of social life. Monk says Finn has “bottom” by which he means “determined rider,” and this has reference back to George Vavasour who “didn’t stay the course” (3:6) and suggests Finn will. Tenacity is the value here. Madame Max brought in and it’s made clear through shots that she and Finn are parallels, both outsiders. I counted 33 separate conversations between pairs and trios of characters.

Scene 3) Mrs Bunce (Brenda Cowling) preparing Phineas’s bed in his lodgings, then he comes in and she gives him beef tea and bread; the camera and dialogue focus on the photograph of Mary Flood Jones (Maire Ni Ghrainne) on his mantelpiece. The dark, simple provisions and needs of Phineas and Mrs Bunce’s words that she hopes Phineas won’t forget where he came from are contrasted to the glittering party of extravagant luxury we have just seen. A plain dark room, mother figure, humble meal & Mary Flood looking like school girl love.

Mrs Bunce and Phineas: he has some late night beef tea and bread; she hopes he won’t forget what his origins are

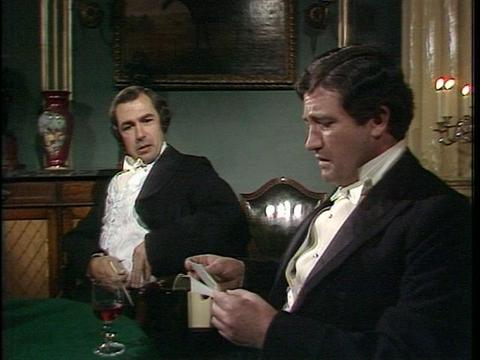

Scene 4) we are back in the familiar club room we’ve seen in so many episodes before and with our choral figures, Barrington Erle (Moray Watson) and Dolly Longestaffe (Donald Pickering). Longestaffe wants to know why Erle is not at Lord Brentford’s party and Erle says he is “surfeited with glutinous Irish charm” and does not want to see his cousin, Lady Laura (Anna Massey), making “such a fuss over Phineas Finn.”

Episode 32: “Sizing Up Finn.” The scenes swirl around Finn as the characters interact with him, discuss him, and we see the pressures he is under and choices he makes. Scenes 5 & 8) Lord Brentford’s Dinner Party, the large drawing room. Phineas meets Violet Effingham, and beyond Chiltern’s (John Hallam) brief debate with Finn over whether office precludes a man being an honest politicia; Phineas in the film explicitly defends his seeking office: a man must eat; we witness Chiltern’s violence toward Violet and see something of Lady Laura’s devotion to her brother (which he seems not to deserve). Again we have the theme of a super-devoted sister—common across Trollope’s novels and in the story of Kate and George Vavasour (Karin MacCarthy and Gary Watson) in 1:2 – 3:5. Out of jealousy Phineas one-ups Kennedy (Derek Godfrey), his rival for Laura’s hand in marriage; Laura insists he apologize, and he forces himself to, and (to his surprize) this results in an invitation to Loughlinter.

Phineas making a joke at Mr Kennedy’s expense; all parading in to eat the luxurious dinner turn round

Scene 6) Lord Brentford’s dining room, the actual dinner table, where sitting arrangements epitomize relationships; Lady Laura central at the table’s end.

Scene 7) Mr (Haydn Jones) and Mrs Bunch’s kitchen downstairs: the contrast again between the world of the rich and this couple, where the man eats very plain food in a wooden bowl, & he and his wife do the dishes together; Mrs Bunce disses Bunch’s trade union, and Bunce shows his suspicion that Phineas’s success will teach him not to follow his conscience.

Scene 9) again we end in the club, this time watch and listen to Fitzgibbon first casually ask and then demand from an extremely reluctant Phineas his signature on a bill for 300 pounds in return for all Fitzgibbon has been teaching and providing (including membership in this very club). It’s 250 in Trollope and the pressure is not explicit; in Trollope Phineas feels pushed simply by gentleman’s friendship. In Raven Fitzgibbon’s mentoring comes at a price (he has been in every scene where Phineas has been with powerful politicians and came to Phineas’s lodgings to help in 3:6).

Episode 33: “Loughlinter.” Scene 10) Phineas driving in a carriage in the landscape leading to Loughlinter. This corresponds to Alice Vavasour’s (Caroline Mortimer) first trip through the grounds of Matching Priory; as she was awed, so is Phineas, only Phineas is wry and she delighted in Lady Glen’s stories and the place. Sceen 11) the front of the mansion where Phineas meets the butler and hears the “Laird” has gone up to the folly with Lady Laura.

A reinforcement of the cultural disparity between the rich Scotsman and Phineas, the poor Irishman. Their rivalry for Lady Laura’s love is brought out in Scenes 12 & 13) in the frist high on the hill Kennedy speaks at length of the danger someone like himself has in being a man apart from others (this anticipates his madness to come) and afer Kennedy has left, when Laura and Phineas move to a knoll lower down, we see that Phineas is trying to make love to Laura and she putting him off; both say they have no money whatsoever. Money an emphatically important factor in Raven and Trollope. Scene 14) on the terrace, Phineas and the major politicians, Lady Laura, Lady Glencora discourse in epitomizing ways about the doctrine of equality (Phineas says people can be made more equal materially, they cannot in character. These are in fact improbable conversations between politicians (as in from Phineas later on:”This from you Mr Monk?”); people don’t talk so directly or explicitly, but in dramatic convention such discourses are accepted.

Central players, Phineas, Mr Monk, Lady Laura, Lady Glen, Plantagenet, in the background, Madame Max and Barrington Erle in their parts assembled on the Loughlinter Terrace

The party breaks up so we see Phineas and Monk together where Monk counsels going slow on reform; off to the side are Barrington Erle and Madame Max. Her presence is not probable as Kennedy owes nothing to Omnium (Roland Culver), but Raven wants her there to keep anticipating a coming relationship with Phineas: her few comments at Lady Glen’s party here to Erle have been to support the idea of reform if not going for it practically just at this moment, and to speak sympathetically of Phineas (“He is young and restless, Mr Erle. I think you will find he will settle down”).

Scene 15) an immediate juxtaposition of Madame Max (the scene at the terrace closes with her) and Mary Flood Jones (Maire Ni Ghrainne). One of Raven’s problems in Pallisers 4:7 is he must juggle a heavily political story where he shows men in public life yet politicking in private, and imagine large group scenes, at the same time as he is trying to carry on four different love stories: Phineas and Lady Laura, Phineas and Madame Max (brought in early and attracted to Phineas), Phineas and Violet Effingham (at least Phineas for Violet once Laura rejects him), and Phineas and Mary Flood Jones. Here we have what we are to take as a worldly sophisticated woman who has a heart contrasted with an innocent unsophisticated woman who also has a real heart and will follow it.

Mary waiting to catch Phineas’s father, Dr Finn (Desmond Perry) riding by

Raven manages pretty well to give depth enough to the various stories but it’s a struggle to present appropriate epitomizing scenes. Here we see Mary patiently trying to find out what is happening to Phineas now. We know he’s at Loughlinter—so there is a parallel of scenery, the rich laird who owns so much gorgeous scenery, much of it cultivated nearby and the struggling doctor and young woman in Ireland. We do not get a real picture of the devastating poverty or Ireland, but then there is no representation of the same condition so widespread in Scotland or England. The scene ends on Mary watching the doctor ride away so again there is a juxtaposition as now we turn to

Scene 16) The terrace at Loughlinter, nighttime still, Monk and Phineas in conversation. This is just the sort of moment Phineas has longed to achieve:

Here briefly we get the matter of whether to take office debated (in Trollope the debate is at the center of a long Chapter 18 and is held between Turnbull whose position is fortified because he doesn’t take office and Monk who argues he may make a difference by compromise). Madame Max approaches Phineas and reproaches him gently for not coming over to her, he apologizes and we feel it was not deliberate, but we do remember that Lady Laura had urged Phineas to stay away from Madame Max:

Phineas has been eyeing Lady Laura who has been glimpsed all along in the further reaches of the terrace with Kennedy, and as Madame Max is about to respond to Phineas’s candid comment he hasn’t enough money to hunt with Chiltern (much less go to Vienna and Venice as she is about to do) with some help (we know if we’ve read the book and feel if we haven’t), he sees Lady Laura and like a fly to a honeypot, he rushes up the stairs to her; she looks sombre, dark as she agrees to meet him tomorrow. She has already accepted Kennedy’s proposal.

Episode 34: “Disappointment.” Scene 17) on the beautiful landscape high on Loughlinter, Phineas asks Lady Laura to marry him and she tells him, it is too late; he is angered at this as he had really believed she might accept him; she responds to this by saying she married Kennedy because she had paid her brother’s debts, was broke, and thought she could not marry unless she did so for large amounts of women. In the film she is cool and demands Phineas be courteous about Kennedy, while he exhibits genuine sexual jealousy, but at the last moment she rushes into his arms for a fervent passionate kiss; in the book the scene is the same but she talks less coolly and speaks of “wiser” heads prevailing; this latter remark shows the parallel more clearly between how Lady Glen was married off in 1:1 – 1:2; the difference is Lady Laura has sold herself when in fact she didn’t have to. Her temptation was not a self-destructive man, but she could not do without the rank and money. This fits Raven’s conception of a woman constantly (in the various scenes) counseling performative behavior, urging subtle sycophany, and ostracizing people. Trollope’s woman is far more passionate and does not understand this element in herself is strong.

Scene 18) the terrace again at Loughlinter: a dissolve from previous scene and now we get close-up of Laura’s grim face.

Films are to be read visually, and we already see her paying the emotional price for her decision; in this scene she and Kennedy talk and their gloved hands, fancy clothes and careful courtesy are not really warm, while we get a slight clash over his insistence on it’s having been God not Fate who brought them together, followed by her justification to him of why she tells Finn about family matters like Chiltern’s present solvency. This is a contrast to Scene 19) Irish countryside, Phineas and Mary Flood Jones walking along side-by-side, she teasing and he not flirting with her, only speaking plainly when he tells her Lady Laura Standish has married someone else and he has not gone to the wedding because he has no money “to be flitting to and for to other people’s weddings.”

Scene 20) Mr and Mrs Bunce’s kitchen, this time Mr Bunce with his mates drinking and talking politics: Bunce says they must “stay solid with Mr Turnbull and The People’s Banner (a newspaper), one man warns Bunce, “no violence” (which he is capable of, as he’s played as hot-headed and not thinking before he acts or speaks); they are interrupted and shooed away by Mrs Bunce. Irony: the woman is powerful; this is a continual reversal in film adaptations of Trollope: repeatedly the woman are shown to be the powerful people (see Plater’s Barchester Chronicles); ends with a sound and Bunce asks “Is that the front door?” Scene 21) Outside the Bunce’s door a gloved elderly man with a high hat, and apparently genteel ways but not a working class accent; Mr Clarkson (Sydney Bromley) has come to see if they have a lodger named Phineas Finn, and forces himself in; Scene 22) back in the kitchen, the man reveals he’s a debt collector and Phineas owes him a considerable sum (though has not had a penny himself).

Episode 35: “Parliament Resumes.” Scene 23) back to 24 Park Place, and Lady Glencora playing peek-boo games with child in luxurious cradle and golden rattle in his hand: to her Plantagenet Palliser and they enact a scene of companionable marriage, she sitting on his lap, and he acting affectionately to her and the baby; they are partners seeking social success, he to influence the way money is handled; she to build his power. Raven reinforces stereotypes about men and women in marriage. This scene brings before us this chief couple across the whole series in this way to suggest the horizon of values against which we are to see Finn’s efforts—and eventually Madame Max’s on Finn’s behalf. We are not to worry about how probable this is or how they overcome all their differences; they are figures shaped by a new design; the scene is a movable emblem, and is contrasted with a key couple in the Phineas matter in Scene 24) in Kennedy’s drawing room in London: Lady Laura and her husband Robert Kennedy reading side-by-side, he looking over at her book to see if he approves. They are stiff. Phineas comes in and then Violet Effingham, and we see Violet and Phineas again spontaneously like one another, as well as Kennedy’s controlling behavior: he welcomes Finn to his house, but Lady Laura has to in effect ask permission to stay with Phineas when Kennedy leaves.

Their dialogue again on Chiltern, this time with the accent on Lady Laura’s expectation or desire that Violet should marry Chiltern so as to bring her father to accept Chiltern again; and then Scene 25) Chiltern and Phineas drinking at the familiar club, with Chiltern urging Phineas to come hunting, while we get ominous comments about Kennedy, Laura not having any money, & Chiltern’s own fierce love for Violet. McCann’s facial expression in this scene reminds me of Barry Justice as Burgo Fitzgerald where he too was at the club and listening to powerful people making decisions which they do not realize affect his fate but he could do nothing about. It’s a flat look.

Scene 26) Lord Brentford’s drawing room, he walking with Violet Effingham, his niece. Lady Laura had said he was lonely and Violet is keeping him company. Chiltern bursts upon them, and when the father retires, we get an edgily violent scene with Chiltern grabbing Violet and insisting he loves her when she refuses his offer of marriage and attempts to retreat from him and says “I cannot give you that for which you ask.” On Trollope-l Nick has argued that Trollope is “comfortable with male violence,” especially when the male is upper class; I’ll add to that that Raven endorses the idea women like to be beaten (which Trollope hints he believes too); Raven is cruder in his portrait of Alice panting over Grey’s fighting with George Vavasour; in this first phase of Raven’s presentation of Violet and Chiltern, Raven presents Violet as terrified, but later on when Chiltern controls himself a little, Violet is drawn to him (irresistibly it seems).

Chiltern roughhousing Violet Effingham, forcing himself on her while saying hoarsely “I love you” over & over again

The larger scheme has Phineas contrasted to Chiltern and again the benign protective kindly male (Palliser, Grey) is the hero the series consciously endorses; much farther along in the series Emily Wharton (Sheila Ruskin) will make a serious mistake when she does not attempt to set any limits on the sexual possessiveness and uses of her made by Ferdinand Lopez (Stuart Wilson) before and during their marriage (this story matter is dramatized and interwoven with the story of Palliser as Duke of Omnium and Prime Minister in (Volume 10, Part 20 to Volume 11, Part 23).

Scene 27) Phineas’s room in Bunce’s lodging house; the room is dark (lit by a candle) and Phineas in evening clothes now loosened and without his jacket., He is practicing a speech which seems hard for him to do not because (as in Trollope) he’s new at it, but because he is saying something he doesn’t agree with but knows he must assert to be accepted: that reform must still be put off; Scene 28) the stairwell, with Bunce on the way up having said goodbye to a political crony, Bunce indignant at Phineas (“he calls hisself a radical?”); and the last Scene 29) Phineas’s room: as Bunch begins to get obstreperous, Mr Clarkson (Sidney Bromley) makes his way in and demands payment for Fitzgibbon’s bill which has slipped Phineas’s mind; he will not go away. And so 4:7 ends on an emblem of the price Phineas is going to have to pay to reach power and do (probably limited) good. This sudden dark ending with its bleak irony matches the ending of a number of the episodes so far; at their brightest they show life simply going on.

Phineas listening to Mr Clarkson’s patient nagging

The many many immense differences between 3:6 (which began the Phineas Finn matter) and now 4:7 (where we are in the thick of the new novel) and Trollope’s opening quarter of Phineas Finn, the three very long wholly invented social scenes, the scenes of political talk, many of the shorter scenes at the Bunce’s and the utter difference between Raven’s arrangement and Trollope’s show how necessary such changes are as well as where Raven departed and how he interpreted Trollope to create an analogously rather than apparently faithful film.

Mr Bunce politicking with friends

What I haven’t tried to do is answer the important question Nick did on Trollope-l for Thomas, Conklin and Birtwistle’s film adaptation of Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford, My Lady Ludlow and Mr Harrison’s Confession: how does the Phineas Finn matter relate to what was going on in cultural and social life in Britain in the 1970s; I’ve provided a description of a less difficult matter: how the art of these mini-series works.

Sylvia

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- Brilliant as ever Ellen.

I just want to dwell a minute on the issue of Phineas’s family and money, a subject which, as I recall, is hardly touched on in Raven and is brushed aside in Trollope. Perhaps the latter claim is unfair. The book contains a picture of Dr Finn’s financial position in the very first paragraph….

"And he was a man sufficiently well to do, though that boast made by his friends, that he was as warm a man as the bishop, had but little truth to support it. Bishops in Ireland, if they live at home, even in these days, are very warm men; and Dr Finn had not a penny in the world for which he had not worked hard. He had, moreover, a costly family, five daughters and one son, and, at the time of which we are speaking, no provision in the way of marriage or profession had been made for any of them."

Dr Finn is 'sufficiently well to do' to live a life of comfort in rural Ireland. Indeed were he not supporting Phineas he would, Trollope specifically tells us, be in a position to retire (a fact which causes his rival Dr Duggin to dislike Phineas!). Phineas's adventures come at a considerable cost to his father and his sisters (who have no provision made for them). Now it has to be said that this matter is soon lost sight of in the book. In London amidst the Kennedys and Pallisers Phineas is a very poor man. But objectively he is not poor in the sense that the Bunces are poor. He always has the option of retiring to Ireland and living a comfortable life as a rural lawyer.

Raven's stress on Phineas comparatively impoverished origins do add dramatic strength and concentrate our minds on this aspect of his story. Which I think is commendable. But the near complete omission of the effect on his family (the cost) emphasises how this is also lost sight of in Trollope. But it is plainly stated.The inequality of treatment of the son and the daughters is starkly clear to modern eyes.

Nick.

— Nick Jan 29, 8:34am # - Nick, mostly on Trollope’s book:

“Well here we are again – a devoted sister helping a less than deserving brother. I wrote at some length on the topic in relation to Kate and George in CYFH, and referred then to the talk on the subject I heard at the Exeter Conference and also reflected back to the case of Sowerby and his sister Harriet in Framley Parsonage.

I don’t want to repeat myself but here the same scenario is played out with some variations. And indeed we have another case – that of Phineas’s sister Barbara and Mary Flynn.

Quite clearly this theme is a recurrent one. But each time with

variations. For the first time we have here a man – or men if

we include Phineas – who is worthy of his sister’s devotion (at least in Trollope’s view if not mine :)).

But the strange thing is that in terms of the outcome for the sister (Laura) she fares far worse as a result of her devotion than either Harriet or Kate. Far worse in terms of the fate that Trollope imposes

on her that is. And he doesn’t overtly criticise Laura in the way

that he viciously assaults Kate.

(>>Kate had been a wicked traitor—a traitor to that feminine faith

against which treason on the part of one woman is always unpardonable in the eyes of other women.Mary had received from Barbara Finn certain hairs supposed to have come from the head of Phineas, and these she always wore near her own.

— Elinor Jan 29, 9:41am # - I was all set to write about Raven’s portrait of Lady Laura compared to the in-depth psychology of Trollope’s portrait of Lady Laura Kennedy (poor Lady Lady Standish that was): this time this attracts my attention. On its own terms it’s remarkable: she begins as a strong dominating woman who, together with her cousin Barrington Erle, jump-starts Phineas’ career. Erle does it because he saw Phineas at a place other men of the type gathered, and others saw how intelligent, pleasant, and eloquent he could be, and they needed someone to talk a spot a Tory seemed about to lose; Lady Laura is attracted to someone she can at first dominate and direct, a mentor. She can’t be in Parliament herself and Trollope assures us nor did she want to. From this self-possessed young woman who runs her father’s house, she degenerates slowly into a woman made to submit to her husband, and then into a woman made nervous because of the continual grating on her nerves of his controlling rasping ways which are justified by her community so she is in the wrong; she gradually loses her self-possession, her self-esteem, and is shattered by the end of the novel. This trajectory is one that usually from other literal causes psychiatrist and sociologists have traced in the case of women who marry abusive husbands; the most apparently independent woman can turn into someone unable to fend for herself, even to driving alone in a few years when set into a situation where such a man is her husband and the society leaves them

alone together.

I think many reading Trollope pay attention to this level of the narrative and this enables them to ignore the larger issues by which he does consciously shape his narrative, though he doesn’t see the immorality of much that he presents as perfectly okay. I put up Chiltern’s posturing in the club in front of Phineas on our groupsite space from Raven’s film as Raven does follow Trollope in justifying and even liking Chiltern. Raven goes further as I’ve said in that he makes a joke out of male violence in his film and presents his Alice Vavasour as panting for it. Raven’s Alice Vavasour is physically attracted to George in the films; Trollope’s is revulsed because she has been engaged to John Grey and in the era’s terms that means some sex, so “naturally” a chaste woman cannot change partners. (Freud argues the virginity taboo is there to make women cling to one man as they “naturally” ....)

I read Nick’s posting as a kind of revelation and want to go further than he—perhaps he wanted to leave the inferences out so as to be tactful. It seems to me that Laura is punished because she betrays a man. Kate only betrays a woman; Barbara only sets a woman up for a man (as Kate does). Harriet supports her brother and is obedient and loyal to her husband.

The key here is women are expendable; dismissable; the attitude here is one which can lead to honor-killing in some societies, and in Trollope the brothers do end up at times murdering the sister’s seducer and the sister is blamed intensely for bringing this on him; she is sent away or dies (The Macdermots, Trollope's first book is more candid and shows some pity for the sister as she is a victim, but she dies of a miscarriage on the floor of the courtcase—humiliating physically shocking death in public too). Rememer how Trollope in Orley Farm presented Lucius Mason’s attitude to his mother and how she kneeled in total abjection to him because her life-long lie and self-erasure has resulted in trouble for him.

I noticed that Raven’s conception of Laura is even less sympathetic because psychologically Trollope goes deep into her case and ends as he does with most outcasts pouring himself into her (as he does with Josiah Crawley let’s say and a host of depressive people who are the centers of the most powerful tales). Trollope also does not have his Laura urge Phineas to ostracize anyone; Trollope’s Laura does not really scold him in the way Raven’s does and drive him to grovel (in the way Raven’s does); Trollope’s Laura is not later willing to pressure Violet to go for Phineas so abjectly (as RAven’s does). Some of this is the result of time constraints and the objectification of drama (Unless you use voice-over and in these films this “feminine” intellectual device—bad-mouthed until very recently—is avoided.) But Raven unlike Trollope is not sympathetic to the inward deeply disillusioned person like say Alice Vavasour and has no understanding it seems to me of this level of Trollope’s fiction; he does loathe the outcasting that networking and making powerful communities partly depends on.

And he likes woman only insofar as they serve men; his Madame Max is a version of the European femme fatale type made chaste, but more on that when she emerges as the secondary heroine of the series. Right now she is on the stage near a door looking in (as is Mary Flood), and Phineas is running after a false goddess (as Raven would see her).

I would like to like Lady Laura in the films; I can’t. As of 4:7 I can’t Lady Glencora, and probably won’t again until we reach the matter of The Prime Minister and then only in part. I can feel for Laura very much as I do Trollope’s other deeply anguished portraits of nonconformists (for that is what she is too) in the novel. Trollope said she was his strongest character and I think he knew his gifts were in melancholy (he puts it they are not for comedy by which he means broad comedy; irony and satire he can do; only once does he do some merry comedy, Barchester Towers, and it remains a sport in his oeuvre).

Ellen

— Elinor Jan 29, 9:42am # - Another note:

Listening to David Case reading aloud Phineas Finn and thinking about the film adaptation, I’d like to say we should emphasize how likable Phineas is to the reader. He’s that way because Trollope does know what’s instinctively liked, and he wants us to see the rise of Phineas is partly a product of his pleasantness.

I felt on getting into the early part of the Phineas matter (3:6) in Raven a breath of fresh air come into the film; he was just so unassuming and quiet and candid and idealistic—that first scene in a corridor of power showed him determined, tactful, but no sycophant. As the films and novels progress, he never betrays a woman (the way Lily Dale feels and I agree Johnny Eamese betrays in in The Last Chronicle); his violence is reactive. He really cares about Bunce, and much else. In the film he gets Mary Flood Jones pregnant and never waves in his determination to marry her—though it puts a double-whammy end to his career (temporarily).

I think this element of the novel important because it shapes the tone of both books, especially first where Phineas is more innocent, and accounts for their popularity.

Ellen

— Elinor Jan 29, 1:05pm #

commenting closed for this article