Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Pallisers 7:14: The world as moral vaccuum;and the extreme difficult of re-entry · 4 September 08

Dear Friends,

I’ve put 6 transcripts of the brilliant scenes of 7:14: Rejection; Abandonment and Male Obduracy; and Our natural business lies in escaping. Here now is a concise summary of the episodes accompanied by thematic and comparative commentary.

Several Trollope critics have connected Trollope’s Eustace Diamonds and Phineas Redux thematically; in The Changing World of Anthony Trollope, Robert Polhemus picks out themes that cohere with one I found in 7:13: he calls the “subject [of The Eustace Diamonds] nothing less than the loss of the self.” Its heroine, Lizzie Eustace is “a brainwashed nullity blown about like a tumbleweed on the winds of public opinion” and her novel’s world is a “moral vaccuum,” with Lord Fawn more like “a shuttlecock than a man”; so too does Raven’s Frank (Martin Jarvis) let himself become that, and George (Terence Alexander) her follower; the police in this part will take a mild revenge for having been so used. Polhemus says “scepticism colors the mood” of Phineas Redux. Trollope had himself since Phineas Finn “experienced the vicious, scummy side of political life;” while Trollope shows “the inevitable ravages of time on people” (we saw that theme in 5:9, Time is pressing us very hard, Mr Finn and it returns when we see and feel the characters aging in 8:15; Polhemus’ comment that in Phineas Redux Trollope delves “the brutality and insensitivity of political life” seems especially apt for the Phineas scenes in Episodes 29 and 30 of this part.

Another way of summing this one up: Raven and Trollope interested in outsiders breaking in: Lizzie (Sarah Badel) ejected, Phineas (Donal McCann)back to try again.

The summary.

Episode 27: “Rejection:” Scene 1) Fawn Court, front room, focus on fireplace and corner of table. A wholly original invention, between Lord Fawn (Derek Jacobi) and Clara Hittaway (Penelope Keith) where she says flatly that it’s quite “clear” Fawn is quit of all obligation to Lizzie (Sarah Badel); this functions to inform the viewer that strand of the story is over; the story of Fawn and Lizzie Eustace is ended emphatically; the new turn is Clara’s (now reiterated) determination to get Fawn to propose to Madame Max (Barbara Murray). He is watch for Madame Max’s returns from Matching Priory and rush out to “attack” her. The battle imagery is meant to amuse against the backdrop of Fawn’s diffidence and dismay (e.g., Clara: “You must advance on all fronts immediately; Fawn: “But Clara, she has withdrawn her position …”); the scene has a “prop” of a canary bird in a cage; usually such caged birds stand for women (as in the 1979 Pride and Prejudice where in the front room at Longbourne we see a bird in a cage every time we see that room)

Fawn as canary with Clara Hittaway standing by

Scene 2) Matching Priory. Madame Max reading Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” The poem which the Duke (Ronald Culver) beats time to with his hand characterizes his taste; it also harks back to Fawn’s dialogue with his sister (e.g., “Clara. ‘You must outflank her retreat.’ Fawn: “I can hardly start outflanking Matching … ’ Clara: ‘Others might. But I see the task is beyond you.’) and again emphasizes the subtext of emasculated men (the police say Lord George didn’t take the necklace because it’s beyond his strength; he says Lizzie is beyond him). Lady Glen (Susan Hampshire) comes in and recites by heart with Marie and they laugh. A companionable moment:

Madame Max and Lady Glen recite to Duke

Lady Glen (as she has before in these semi-choral scenes) brings a letter, this time with news of Phineas Finn (Lizzie is ceasing to be the subject of gossip for the Duke); we hear Phineas is about to be a father. The Duke, instinctively sensing Phineas is his main rival, disparages Phineas; Madame Max goes to the back of the room to avoid anyone seeing her face.

Scene 3) Ireland, Phineas and Mary’s bedroom. A contrast to the previous where the Duke and Lady Glen had laughed over the the brevity of the time between the marriage and coming childbirth. Mary (Maire Ni Ghrainne) has just given birth to stillborn child and has to be told:

!

Mary Finn dying

She dies almost immediately. Phineas moves to the window where the focus stays for a few seconds getting blurrier and closer:

Phineas grieving

Trollope presents this scene in a sentence spoken in the character of Laurence Fitzgibbon, apparently flippantly, Mary died before she gave birth, apparently in a late miscarriage which produced a stillborn baby (not clear whether viable or not, i.e., what point in the term of her pregnancy); in the film she gives birth to a stillborn boy at the end of a difficult pregnancy. It’s moving and McCann’s silent performance inimitable.

Trollope rarely gives us death scenes; he gives us the reaction of the living afterwards; and most of the time soap opera aesthetics mutes this kind of thing. But Raven has done a sort of justice to Mary. Though presented as innocent, an entrapper, we have had a trajectory of her life from a young woman waiting for Phineas’s father to hear news, to the courtship, to marriage, and now death. In visual drama the viewer would feel odd were the presence shuffled off with a sentence or so. We do see what her hopes came to, and in this part Phineas tells Marie how miserable marriage can be (see transcript of this later scene in the part). We are told in the novel Phineas hid his discontents from Mary. Trollope is more contradictory and has his narrator also assert Phineas would have been happy, would have stayed contentedly all the while in Chapter 1 of the novel Phineas quickly succumbs to Erle’s invitation to give up his permanent niche, and Trollope has Phineas neighs like a horse who wants to race in the big arena among trumpets.

Scene 4) Hartfield Street front room, the scene where Frank (Martin Jarvis) is finally definitively alienated from Lizzie (see transcript and stills). The scene between Phineas and Mary, continues to be used as a parallel for the debased and demeaning (morally stupid) and cowardly clinging behavior of Lizzie Eustace (Sarah Badel—on this unfortunate actress’s behalf, used here as an icon of women, she reads some of the novels put out by Cover-to-Cover cassettes and does them dryly yet passionately, a fine reader). We are never to see Lucy Morris apparently, as also Lady Greystock and the characters which bring out the plight of women without these families who are gentry.

Scene 5) Fawn Court, Fawn writing a letter. Could this be an allusion to the truthful letter Lord Fawn writes to Lizzie in the book (Trollope, Eustace Diamonds, New Penguin ed Stephen Gill, Ch 67, p 647-48), and this interruption could account for it never getting to Lizzie? Clara barges in; Madame Max back from Matching Priory.

Clara interrupts Fawn writing

She shuts his pad and he gets up weary. It’s notable how dark all the scenes have often been which are sheerly Lizzie matter. The early scenes of politics at Loughlinter are dark too—especially on the terrace where Laura (Anna Massey, not in this part) originally accepted Kennedy (Derek Godfrey, not in this part)

Scene 6) Madame Max’s flat (boudoir really), the scene where Fawn proposes, Madame Max negotiates, and they end on a draw (see transcript and stills). Exquistely well done comical scene. The big bully of the two and one-half episodes, the woman whom no one seems to stop (except of course she seems egregiously out of funds and living a frustrated life with her mother and 6 sisters and invisible husband), Mrs Hittaway (Penelope Keith), has once again driven Lord Fawn to court Madame Max. A less subtle and humane, more sheer clowning scene, which included Lady Glen came towards the close of 7:13 (Episode 25, “Fawn’s Attempt,” Scene 24). What made this superior was the tone: Madame Max suddenly appears to take Fawn seriously, and exposes his lack of attractions, financial too; he in turn shows his discomfort with the illegitimate parades of masculinity.

Episode 27:” “George Leaves:” Scene 7) Hartfield Street, front room. Paralleling scene 4, George (Terence Alexander) definitely breaks with Lizzie Eustace (see transcript and stills). The actor, Alexander, transcends the material. Lizzie has had one last try with Frank Greystock who walks out preferring the invisible governess. Indeed throughout the episode men desert in droves. Lord George is presented as afraid of her: he wouldn’t be able to sleep lest she steal the gold from his teeth. She is too much for him.

The story matter from Eustace Diamonds in general credited the women with intense power over the men throughout. This reminding me of the way Alan Plater’s The Barchester Chronicles: the film worked similarly—flattering the female watcher, and reinforcing ideas about male viewers they are much put upon and long-suffering and even without power). Except of course they don’t really have power. Lizzie could be arrested. She is dumped; she doesn’t dump others. She is only saved by the money left her by her husband.

When George comes to her room he seems a really decent man, under Jane’s (Helen Lindsey) thumb in a way, and wanting to know the truth, to set things straight. Lizzie again pretending emotionalisms. When he asks his question, we can see that to him she’s the boy who has cried wolf all too often. This is a strongly misogynistic scene if you believe in the portrait of Lizzie Eustace and think she stands for a real type of women before whom men can only flee. Maybe the Frank rejection scene and this one taken together are a modern male nightmare of women.

Scene 8) Matching Priory, the Duke’s bedroom. This one consists of two phases, first the Duke of Omnium and Lady Glen chat with the Duke of St Bungay (Roger Livesey) and Palliser (Philip Latham); then Lady Glen and Palliser engage in a tense scene where she loses as he remains obdurately unwilling (or unable) to help her care for the Duke or bring up their children with intimate affection (see transcript, stills, and commentary). In the second half we have the wretchedness of Lady Glen and Plantagenet’s grim refusal to understand or help her(see transcript and stills. About the first half Nick Hay commented on Trollope-l:

“There is one especially compelling scene where Omnium, Glencora, Plantagenet and St Bungay discuss the forthcoming elections. St Bungay basically says that they will have to offer some ‘reforms’, Omnium remarks that they will reform everything (he means the power, money, status, privilege of the ruling class) away but Glencora explains that in fact the strategy is that you give a little away so you can retain the vast majority and keep privilege intact – this is the job of the Liberals. Plantagenet protests that these are serious matters and that even though his decimal coinage proposal is a good idea, it is of no use to the many with no money at all. St Bungay replies that there will always be those with no money, it is the nature of things (I am crudely summarising – as Ellen has often remarked what is needed is a screenplay).

Lady Glen with Duke mocks Duke of St Bungay and Palliser’s high minded stance

All this, whether or not it has a basis in any actual conversation in the books [it has no literal basis at all), the scene strikes me as intensely Trollopian. And we have four adults making adult conversation. Glencora’s is the most telling and insightful contribution of all. No infantilisation here. The politics are, of course, those of a certain kind of ‘reformer’ throughout the past two centuries and Glencora’s analysis holds good today. But the scene works in a visual way because it is staged around Omnium’s bed with St Bungay and Plantagenet sitting on chairs and Glencora at his side; there is a certain suggestion of heirs waiting to pick the carcass of the dying man (and of course Omnium’s world of aristocratic privilege is indeed dying or dead and being replaced by a newer, subtler ruling class which St Bungay at least wishes to guide).

Duke of St Bungay trying to influence what is to occur, Palliser and Lady Glen waiting for death of old man

It seems that here Raven’s cynicism chimes with Trollope’s own and we get back on track into politics as the book defines these.

The old order in desuetude and the new not yet born is indeed a theme of 7:13

Episode 28. “Outcast:” Scene 9) Hartfield Street, again the front room. Another remarkable scene but as I’d already transcribed six, I forwent this one. Sergeant Bunfit (James Cossins) comes apparently to tell Lizzie that the diamonds have been declared hers. In Trollope’s novel the parallel scene which this one does draw on (at least as an event) Major Mackintosh flatters, cajoles, and maneuvers Lady Eustace into telling the truth (Chapter 68), by insinuating she will get off easy in court; and she does, with Frank as her accompanier. The class barriers are protecting her.

Lizzie in momentary triumph, thinks she’s won

By the end of the scene, Bunfit and Major Mackintosh (Iain Cuthbertson) have categorized her as the only criminal within their grasp, frightened her, and then dismissed her harshly as someone they cannot punish but who will be punished by society as an outcast.

Major Mackintosh judging Lizzie harshly

It’s a sharp severe effective moment; one might say it’s implied in Trollope’s novel, but we are left to feel it’s her moral stupidity and lack of imagination that leads to this as to the last moment Frank was courteous to Lady Eustace; and if neither Trollope nor Raven allows any sense of this, such a woman could find her milieu in another country, say Italy as do Lord George and Mrs Jane Carbuncle. In novel the two crooks are Mr Smiler and Billy Cann; Mr Smiler very much alive and going to jail; Billy Cann turning state’s evidence and Mr Benjamin put away. In Raven, we get the humor of a parodic sentimentality of police over Smiler Jenkins [the name is changed] and Lizzie’s idiotic joining in. Smiler lost the necklace in the campagna, and the two officers look mournful as the campagna is a vast difficult place. Raven is having a little joke (it’s apt since Trollope may well have felt this way about the campagna; it rings true to him). Raven amuses himself with Mackintosh’s imagined scenario of Smiler Jenkins one hundred yards from John Keats and about 30 yards from Shelley in Protestant cemetery; Smiler’s catching malaria (just like Daisy Miller and tragic figures) and the diamonds gone forever. Trollope is less romantic: Benjamin broke them up and they are now in further rich women’s necklaces (one in Russia, a countess for example). We have no crook jeweler in Raven, but instead comic sentiment about the hard life of a hard-working thief, e.g., “Smiler had led a debilitating life …”

The TV dramatic scene is improbable but strong and effective; she has broken more rules than the chastity one; the novel is subtle and truer to life, though not entirely true and her punishment there is more based on her breaking taboos over her gender roles, for her class has protected her. (For my part Trollope has succeeded in making me detest her; Sarah Badel has a similar effect on me in these films. I am glad for Miss MacNulty that she escapes Mr Emilius though Trollope makes her into another silly vain stupid—though also sympathetically desperate—woman who would have succumbed.) When Lizzie falls down at the Major’s feet, she repeats the gestures of Fawn. So she falls to this level of hypocrisy too (though out of different motives and feelings).

Scene 10) Matching Priory, Duke’s bedroom. A wholly invented scene which (as in 3:6 a similar scene on the terrace in Switzerland) serves to re-introduce Phineas and begin Phineas Redux in earnest. As it opens, Madame Max beating the Duke at piquet (Lady Glen had always been losing). (Contrast is that Marie is no outcast; though she breaks other taboos, she is decent and knows what’s permitted in social life.)

Note the sexy picture; Madame Max and Duke absorbed in game

Lady Glen brings in Palliser who says he no longer has news of Lizzie Eustace (“there’s been nothing for months”—a sort of self-reflexive joke); he comes with news of a coming election they hope to win against “Daubeny” (the name is introduced) and that Phineas Finn is returning; it seems his wife had died, so too the baby, and his father has left him enough to live on to make the transition. Again the Duke manifests his instinctive jealousy by disparaging Phineas:

uke disgruntled, jealous of Phineas Finn, Lady Glen smiles at Marie

A close-up on Marie’s face:

She hears Phineas is returning

In Phineas Redux in order for Trollope to get himself into his fiction again (PF was written 1866-67; PR 1870-71, 8 novels, 11 short stories, 1 play and 1 classical study had intervened), in order to recreate the consciousnesses of the previous book and set them going as his storytellers, Trollope has many letters in the first six chapters. Trollope’s Barrington reappears on the stage this way, Lady Chiltern, and especially Lady Laura. He has left these presences in abeyance and lost touch and what better way to bring them back —epistolary personation. This alternates with the satirist’s strong presence which retells the politics ironically and offers free indirect speech moving in and out of a particular politician or consciousness and back to the narrator. We experience Phineas’s visit to Harrington Hall; in this we are told by a detail in a letter Palliser paraphrases that Phineas has gone to Harrington Hall. In the novel Madame Max does not turn up until Phineas’s later second visit to Harrington Hall (after Phineas goes to Dresden); she is not at all part of his return as she is here (and as she was at the first entrance of Phineas in 3:6). All this to set this world going again.

All this makes a terrific problem for Raven, for he must dramatize and the return of Finn; the way he does it is this introductory scene and then the actor (Donald McCann’s) reappearance at the gentleman’s club we have seen before in the company of Mr Monk (Bryan Pringle), the very next scene

Episode 29. “Finn’s Return:” Scene 11) The club. Phineas and Mr Monk walk in; Barrington (Moray Watson) to them welcomes Phineas.

Finn welcomed by Barrington Erle, brought to club by Mr Monk

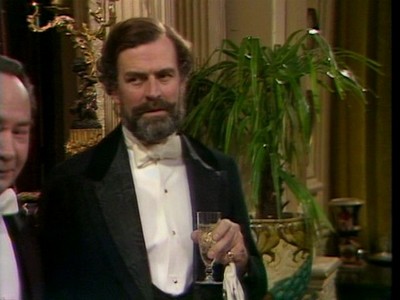

Swiftly we get the first contretemps between Mr Bonteen (Peter Sallis) and Fawn as both walk in next; Bonteen is belligerent, aggressive, but as yet polite (Bonteen: “I am concerned about the Irish, the economics of that wretched country.” Finn: “Yes.” Bonteen: “I am keen to see an improvement.” Finn: That is very gracious of you.”) Monk and Phineas walk off together and begin to discuss disestablishment of the church. Monk says it’s still only in talking stage; over to them again comes Bonteen, and this time, they clash. Bonteen begins with the concrete difficulties of how the queen is the head of the church and who now will appoint bishops, talks of ultimately responsibility, and Finn gets a joke in by pointing heavenwards; Erle comes in with a warning word Phineas should avoid this, and Bonteen expresses the idea insultingly that Finn is just talking. While lighting Bonteen’s cigar Phineas gets his own back:

Bonteen. “From what I remember silence is not Finn’s strong point. Like all the Irish, he has kissed the Blarney stone.”

Finn. (seems to relax). I fear you may be right, Mr Bonteen. We Irish do talk too much. But we try not to talk out of turn. And We do not, Mr Bonteen, gladly suffer men who bray.”

Finn tells Mr Bonteen that the Irish do not like to endure men who bray

Finn and Monk walk off; Erle tries to smooth things by offering cigars all round.

With Finn, returns, Episode 29 we return to the territory of Phineas Finn and Parts 4:7 to 6:12 b(4: 8 particularly) for the first time. Fascinating out this is stretched out (see soap opera aesthetics). By contrast in Trollope’s Phineas Redux,we begin with English politics laid out narratively and interspersed with letters calling Finn back; after Finn goes to Harrington Hall, then his visit to Harrington Hall, we have a moving encounter of Phineas and Laura at Dresden; it’s when we see him first at Tankerville, and he is led to mount a campaign using the issue of disestablishment because his campaign manager, Ruddles, says Browborough otherwise can use his Catholicism against him (Ch 13). No scenes at the club until much later in the book (Ch 34)

Scene 12) Hartfield Street, again the front room. Cat fight between Lizzie Eustace and Mrs Jane Carbuncle (Helen Lindsay). This first is an adaptation of Trollope’s Eustace Diamonds, Ch 71 (see new Penguin, ed SGill, p. 690); then we get a three way between Lizzie, Jane, and George (George really on Jane’s side) and then last scene of our rogues going off (see transcript and stills). To the transcript and previous commentary I’ll add the lines between the money once they stop snide comments are practical when George comes in:

Mrs C: “Lady Eustace refuses to pay what she owes me.”

Lizzie: “Mrs Carbuncle is trying to throw me out because I won’t allow her to cheat me any longer …”

Then they fall to insults, and hitting. I love the alert look in Jane’s eyes; along with Alice Vavasour (Caroline Mortimer), the first Jane (Wendy Williams) of the first Jane and George (Gary Watson, 3:5) or this series, & Aspasia Fitzgibbon (Rosalind Knight, 5:9), Raven’s Jane is one of my favorite women characters of the series. In some moods I prefer Raven’s female rogue (very different in character and action from Trollope’s) to Raven’s Madame Max who is too often a mouthpiece for prudence and the establishment. Jane and George have a certain gallantry which Madame Max is too grave too share—and for which I admit I love Madame Max or Marie too. She is a woman character who implicitly can appeal to older women viewers; she acts out a free life agenda; the one drawback is her scene of pious hypocrisy over the play she and Lizzie go to see.

It is telling how many of the original women are left out of Raven’s version of Trollope’s Eustace Diamonds It has quite a large cast: Lucinda whose mother, Mrs Carbuncle, destroys by her cruel bullying she marry a cruel man for money (Lucinda goes mad); Lucy Morris and the ambiguous figure of Lady Fawn who won’t let Lucy live a real life while Governess; Lady Linlithgow, the mean-tongued bullying employer she has to go to work for; Patience Crabstick; Mrs Carbuncle’s role is diminished (she is Lord George’s mistress not Lizzie). Only Mrs Hittaway is permitted to survive, a figure who enacts repressed sex (so we see another “bad” type of woman from a male’s sexual perspective), and Mary Floyd Jones’s role is kept up to keep Phineas’s married life in front of us. The movie type Helen Lindsay stands for is all we have left.

The last part of this scene is George and Jane’s companionable escape from their creditor (see transcript and stills). One of the rare comfortable moments in the part; others are Lady Glen and the Duke sitting companionable side-by-side in agreement, her feeding him food (traditional) and Madame Max and the Duke playing piquet, reading together. But George and Jane are lovers too.

Scene 13) Palliser apartment in London, in the novel it’s Carlton Terrace; in previous parts of the Pallisers films it has been located at Park Lane. Phineas makes his second important reappearance before the Pallisers and is warmly welcomed; we see evidence of Lady Glen’s relationship with her daughter, Mary, and Mary’s voice; we then witness Finn’s first tense encounter with Madame Max, with Lady Glen and then at length alone (see transcript and stills, which including a comparison with how Trollope brings them together slowly, somewhat later, and without such charged barriers of thought and feeling).

The scene is contrasted to two just before (and by extension the one between Plantagenet and Lady Glen mentioned above). Instead of falling into one another’s arms, being all close and candid, they stand apart. She says she was sorry to hear his wife died, and he indicates his grief and yet his relief and loneliness. She talks of his lack of funds (once again) and how he needs to win, and his immediate problems, he acknowledges this, but asks no help. The scene is replete with a quiet full decency and held-back sympathy. This is the ideal of the series I think. It’s not Trollope’s ideal which is not companionate relationships between men and women

For our purpose here, the function of this scene in the part is to set Phineas Redux going, with Palliser’s hurrying off to St Bungay to discuss coming hopeful election, mark time in the trajectory across the series of the point in time of the Pallisers’ marriage, and put Phineas and Marie back squarely as our second love relationship across the series. The third and fourth scenes which plunge us into Phineas material fully finally (just below) are wholly invented too.

By contrast, in Trollope’s book we begin with English politics, a moving encounter of Phineas and Laura in Dresden, and his visit to Harrington Hall where he is warmly welcomed; Raven puts this off to the next episode; right now he wants to present Finn’s return & how hard it is for Phineas to come back, how difficult it is for people to accept you. Trollope says the Chilterns didn’t write (like most average people), but they took Phineas in again smoothly, with ease, as if he had only been gone a short while.

Episode 30: “Trouble Brewing:” Scene 14) Hartfield Street front room still. This is an adaptation of the genuinely sexy scene (we are to imagine Lizzie goes to bed with Emlius) in Trollope’s Eustace Diamonds, “Once more at Portray,” Ch 79 (new Penguin, pp 757-64) with some admixture of ideas from “Lizzie’s Last Lover,” Ch 73 (pp. 704-712). A pseudo-love scene (a contrast to Jane and George) where Lizzie shows her preference for the false, showy, and meretricious. Emilius’s motives and sexual maneuvers are transparent and she goes for it; like Trollope’s character, Raven’s Lizzie feels she must depend on a man to cope with her troubles and does not attempt to move herself. Raven’s Lizzie doesn’t go out much she tells Emilius; in Trollope she retreats to Portray. Raven does manage to translate the great chapter into sleazy drama.

Lizzie suddenly mesmerized by the conventions of seduction

Nick Hay wrote about the source text thus:

But let us leave these problems and turn to the glories. In Chapter 79 we have the quite extraordinarily brilliant description of Emilius’s proposal. This for me is Trollope at his peak. I can think of few writers who would take a dialogue between such fundamentally unsympathetic characters and describe it with such wit and depth. And in it he finally manages to convey the truth about Lizzie.

“It is everything to me,—death, destruction, annihilation, (unless I can overcome it. Darling of my heart, queen of my soul, empress presiding over the very spirit of my being, say,) shall I overcome it now?”

She had never been made love to after this fashion before. She knew, or half knew, that the man was a scheming hypocrite, craving her money, and following her in the hour of her troubles, because he might then have the best chance of success. She had no belief whatever in his love; and yet she liked it, and approved his proceedings. She liked lies, thinking them to be more beautiful than truth. To lie readily and cleverly, recklessly and yet successfully, was, according to the lessons which she had learned, a necessity in woman and an added grace in man. There was that wretched Macnulty, who would never lie; and what was the result? She was unfit even for the poor condition of life which she retended to fill.”

Lizzie not only cannot tell truth from lies, she actually prefers lies. She believes that lies are the only way to success and happiness. Thus she is in the end a victim only of herself. But even so we can also identify with her in a way that we cannot with a standard ‘wicked woman’, a Becky Sharp, because which of us does not on occasion prefer the lies, including those which we construct about ourselves? Lizzie here transcends her stereotype and becomes a universal figure. If we deny her sympathy we are denying sympathy to the human condition.

But I think we can go a little beyond this and argue that Trollope himself has a certain distrust of language.

bq.”God forbid that you should be hurt. Heaven forbid that even the winds of heaven should blow too harshly on my beloved. But my beloved is subject to the malice of the world. My beloved is a flower all beautiful within and without, but one whose stalk is weak, whose petals are too delicate, whose soft bloom is evanescent. Let me be the strong staff against which my beloved may blow in safety.”

A vague idea came across Lizzie’s mind that this glowing language had a taste of the Bible about it, and that, therefore, it was in some degree impersonal, and intended to be pious. She did not relish piety at such a crisis as this, and was, therefore, for a moment inclined to be cold. But she liked being called a flower, and was not quite sure whether she remembered her Bible rightly. The words which struck her ear as familiar might have come from Juan and Haidee, and if so, nothing could be more opportune.<<

Now Trollope is at one level expressing his distaste for the mingling of the erotic and the Bible (a standard Victorian piety which is wholly unjustified given the content of certain OT books – Song of Solomon etc.). But at another level there is a complete distaste for all of Emilius’s poetic sentiments (which he identifies with Byron – I won’t digress into this side-alley!). Trollope’s preferred lovers (Johnny Eames above all) are inarticulate, stammering men. It is not merely that Emilius is lying; his very command of language is in itself suspect. Truth is somehow beyond language (see how he has given Frank and Lucy virtually no words at all in their big reconciliation scene). A fascinating position for a novelist to adopt.

The scene Raven writes shows little sympathy for either character; Emilius has his Bible which he has successfully used before to enthrall Lizzie (7:13 when he visits her along with Frank and Lady Glen in her bedroom); I take Polhemus to have the accurate view of Lizzie as a cynosure of what Trollope and Raven afterwards presents to us as what prevents us from even seeing what could give us some fulfillment. And in 8:15 the first scene between them as a married couple shows Emilius using Lizzie sheerly as a sex object and taking her money. If you don’t recognize what you’ve got in front of you, and marry it, you will be in great trouble. In the scene Lizzie does assert she will keep control of her money, but as Emilius sweeps this aside, we remember the law will be on his side, and she has never shown any ability to cope as an adult with the world (Raven infantilizes the character, Trollope makes her ignorant of what she needs to know and pretending to know poetry whose real meaning she would never agree with, i.e, Shelley’s Queen Mab).

Scene 15) Pallisers’ drawing room, a salon scene, political party, the first since 5:9 (there was an enormous party in 5:10, but it was not for politicking). We are beginning to have the kind of alternation we saw in the political parts of the Phineas Finn matter earlier in the series: an alternation of love (or sex) with political scenes. Phineas comes in a little after the others, and in Lady Glen’s genial half-comic bow we have memories of his first time at one of her parties (4:7).

ady Glen welcomes Phineas Finn who is watching Prime Minister

We see one element in the trouble brewing (for Phineas) in the disgruntled Mr Bonteen (Peter Sallis) in the corner of the still. In the opening self-satisfied dialogue of St Bungay with Lady Glen, he says there will be no place for Phineas as yet; he’s just returned. Then we see Phineas getting in trouble. Plantagenet moves to warn him against bringing up and backing disestablishment of the church. Phineas says it will happen, and it’s just a matter of time. (This does not seem to be holding true yet.) Lady Glen must come over and harmonize them, but peace is only momentary for Phineas as he is next accosted by Barrington Erle (Moray Watson) and Mr Bonteen. Erle conceives of his function as someone there to soothe people into unity:

Erle. “Congratulations, Phineas. Nice to have you back in the house.”

Bonteen. “I expect Parliament will make a nice change for you from the poor houses in Killaloe.”

Bonteen has just insulted Phineas who is retorting bitterly

Finn. “There are harder people to deal with than paupers, Mr Bonteen. They at least are humble and surprizingly free of malice. If you’ll excuse me, Mr Palliser, Barrington.

Erle (Moray Watson) takes in this moment.

Raven’s stance in the concluding two episodes of this part is crystallized in Phineas’s words to Bonteen’s ironic (sneering) commiseration with him because he had to deal with paupers: it’s very hard to break into a clique, and if you have once gone against the norm, not been entirely honest (which Phineas was not—he was leading a double life as we recall) or what’s expected and caused trouble, you are distrusted. Phineas’s problems are real problems. He might just be hated by such a man. Trollope insists Bonteen’s motive is understandable: Bonteen has spent his life and risen as a useful compliant politician; he sees Phineas as having caused him and his colleagues loss of place, money, and power (when he voted for Irish tenant rights); he also resents and is jealous of Phineas’s handsomeness, and how he is accepted as ever so pleasant.

This rivalry reminds me of how in Mansfield Park Mrs Norris hates Fanny Price: they are after all both outsiders, of lower status; here the men are both climbers. Finn has re-entered the club, is back at parties, is taken in by Mr Monk who stands firm as his friend, but there is no office (the needed salary) and these clashes with Bonteen, presented as an envious man on a lower echelon seething with resentful as someone is taken back after he has done what Bonteen would never get away with doing, are dangerous for him. We who have read the book know they are worse than this; they will provide a motive for the police to accuse Phineas of murdering Bonteen.

Scene 16) The club. Phineas and Erle. This scene dramatizes the matter of Laura which occurs early in Trollope’s Phineas Redux begins: Laura’s (Anna Massey) call to Phineas to come to her at Konisberg, her grief and love for Phineas; her husband Kennedy’s (Derek Godfrey) attempt to stop this and madness. Some of this is introduced through letters. In this scene Phineas is reading a letter from Kennedy, asking Phineas to visit him in London; he has already had a letter from Laura asking him to visit her.

Phineas reading Kennedy’s letter

He seeks Erle’s advice and we see the limitation of ordinary men: Erle is often made to exemplify the common politician, no worse but no better.

It’s a complex scene: Erle is made to turn angry at Phineas, far more than he is in the book, and in this early scene Erle warns him not to go for disestablishment. Again, in the book disestablishment is not brought up by Phineas and only take up by him because of Ruddles and the prejudice against him as a Irishman; in the book Erle had invited Phineas to come and stand and feels a certain responsibility towards him, and it’s only much later that Erle becomes alienated. It’s not just that Raven hasn’t the time; he wants to isolate Phineas and show how he is not accepted and not helped. Erle is irritated because when he gives advice (don’t go to Laura, don’t see Kennedy) it is not followed; but advice is never asked for pragmatic actions but as Phineas says “how the land looks” from “where [Erle] stood,” to see how others will react. To this Erle says: “It looks jolly crooked from anyway round.” Erle is also concerned instinctively that this will hurt the party. He does not recognize subjective loyalties; Phineas does, and this part ends like a number in the Phineas Finn part of the series, with a large close-up on Phineas’s anxious and grave face, now aged.

He has been given a beard to make him older. He stands for Everyman, decent well-meaning version. Probably the closest counterpart for a woman, is Lady Glencora, Everywoman, decent well-meaning version.

In sum, Trollope’s Phineas Redux is deadly ironic about politics itself, with a trajectory about Phineas’s maturing through crisis and depression. He is more expansive and calmer as he looks across a wider landscape; just as dark but from another angle. Raven himself had to cope with re-entering “the world” more than once after it had become a much wider more serendipitous place than the smaller more closely knit one Trollope and his Phineas belong to: you can make it on one contact, which Raven had; you can also lose it if you lose that contact. Raven has to present his matter through epitomizing dramatic scenes with narrowly characterized individuals.

So Raven’s Phineas is seen from Raven’s angle and the scenes are variations upon this expressive theme. I don’t summarize Phineas Redux here but refer those who are interested to Elizabeth Epperly’s thorough analysis and perceptive essay on PR in her Patterns of Repetition in Trollope. I did not see this contrast between the author and playwright and the two renditions last time because I was not reading PR. I have learned you must read the source text carefully, not to knock the new version for its literal distance (that’s fool’s work), but to understand the modern visual dramatic variant and throw new light on the first verbal illustrated (for there are great original illustrations to PR) text.

Ellen

See various links and a concise summary of 1:1-3:6, 4:7, 4:8, 5:9, 5:10, 6:11, 6:12

and 7:13.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

commenting closed for this article