|

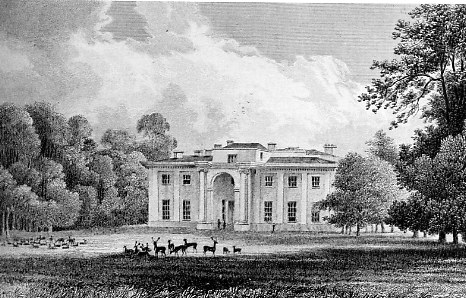

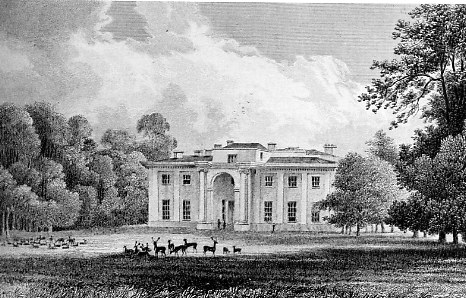

In the nineteen years left to Elizabeth Heneage Finch, she acquired handles. First she and her fourth son, Sir Heneage Finch (our elder Heneage's great-uncle, the jurist and monument-maker) worked at it. He achieved knighthood in 1618. But it was not until 1623/4 after much politicking and the handing over of 6000l. to one Esme, Earl of March, Duke of Lenox, that Elizabeth Heneage Finch and her and Sir Moyle Finch's third son, Sir John Finch, achieved for her Viscountess Maidstone and for him the "Sir." Further similar efforts led in 1628, to Elizabeth Heneage Finch becoming first Countess of Winchilsea, which titles were to revert to the heirs male, in this case to her second son, Sir Thomas Finch, our elder Heneage's father (Physick 6-30; Cameron 38; Reynolds xxxi; I'Anson 52, 55). (The eldest boy, Sir Theophilus Finch died without issue.) About the character of this final deal, of which the later Finches were so proud, we have this gossip in a contemporary letter to Lionel, Earl of Middlesex: "Your Lordship's shee neighbour must needs have a fair large house, for her ordinary one cannot contain the honour; she is now Countess of Winchelsea, and Sir John Finch [her third son] drinks 5000l. by the bargain for his service to the late Parliament So Finches began as the Kingsmills did--with shrewd politicking in Tudor times. The Kingsmills clinched it with lands taken from the Roman church, the Finches by the brilliant marriage settlement. This is not to say that we don't then find persuasive documentation of individual achievements, and a group of remarkable people. As with the Kingsmills, we do. The males first. They were military men, beginning with the Sir Thomas Finch who married Catherine Moyle of Eastwell (I'Anson 46-7); it is in this tradition that the elder Heneage tried partly to bring up his second son, our younger Heneage. They were daring entrepreneurs-- William Finch, yet another son of Sir Moyle and Elizabeth Heneage Finch (born 1591) was an agent for the East India company and sailed across the world to found factories and write down his observations on commerce (I'Anson 47, 55). We have already encountered two distinguished lawyers: Sir Heneage Finch and his son, Heneage Finch, later first Earl of Notthingham. To these we add Sir Henry Finch (died 1625), brother to Sir Moyle Finch, in his time Recorder of London and Speaker of the House; Sir Moyle and Elizabeth Heneage Finch's Sir John Finch (1579- 1631), a Sergeant-at-Law and Speaker of the House too was such another (Physick, 7-8; I'Anson 47-8). Like the Kingsmills, in Tudor times the Finches established a family presence at the Inns of Court, in their case the more fashionable Gray's Inn (Prest 37). The females. Here, unlike the Kingsmills, we can cite two women who do more than simply marry well--though don't knock it, when an Anne Finch--she was either the daughter of the military Sir Thomas Finch and his prize, Catherine Moyle Finch, or Sir Moyle Finch and his formidable Elizabeth Heneage Finch, it's not clear--married into the nearby well-educated and enlightened Kent Twysdens, she made a wise and lucky choice (I'Anson 9, 15, 46-9; Reynolds 423n; Thomson, Twysden, ix). There is the Mary Kemp Finch (she married in), an sister-in-law to our military man Sir Thomas Finch, who made a career as a gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber to Mary I; when Mary Kemp Finch died (1557), she returned a "ring of gold" to Mary I which Mary I had given her "as a signification of my most thankful mynde to her grace for her great benefits done to me" (I'Anson 32, 46). And there is another literary Anne Finch, daughter of the lawyer Sir Henry Finch (Sir Moyle Finch's brother); she married Edward Conway in 1651 who was made Earl of Conway in 1679 the year she died. Although afflicted by migraine headaches all her life, she learned to read Latin and Greek, and became an able Platonist who wrote philosophical treatises. She was friends with the more famous Cambridge Platonist, Dr Henry More, and her letters to him have been published; at the end of her life she was close to William Penn and, despite intense pressure not to, became a quaker (Wiley DNB, "Conway, Anne, Viscountess," 12:50). But even two sparrows do not a summer make. Despite the difference between the wealth, status, and prestige of their families, Heneage and Ann's backgrounds were fundamentally alike, but in nothing is the likeness more important or more striking than in the parallel central role a big named house supported by a group of estates played in both their daily lives. A man was his house; a woman was hers. So-and-so was Somebody at or of Such-and-Such. We are not simply talking self-image here, though this is important; Eastwell and Sydmonton, and to a lesser extent, Maidwell were the social, economic, and political centers of their worlds. The middling and poorer people who lived around these houses were supported by seeing to the needs of the house and its inmates; peers were part of its social network. In other words, in the immediate sense everyone had "a direct stake" in the continuance of such house (Stone Uncertain Unions 502). Thus two children brought up as a potential little master or mistress of such a house will not easily escape the belief that the house is precious, a locus amoenus of peace, stability, and beauty for which much must be sacrificed. Such a child may, as Ann did of Eastwell, create a personal mythic place from the house and its grounds; and we must delve into what Eastwell was allegorically because that's the way Ann and Heneage saw it; but we should also look to the reality of the house, to its real occupants and what it was really like to live in such a place, because in Ann and Heneage's early shared lives this house became a center for ugly familial conflicts. Sadly perhaps, the Tudor manor house, is long since gone. In Sir Moyle Finch's time it had been embattled and expanded; the second Earl swept away a wood; then the third Earl, Charles levelled a hill, took down another grove, rearranged the gardens, and enlarged and modernized the windows (MS Folger 46-8, "Upon my Lord WINCHILSEA's converting the Mount ..."); the later eighteenth-century saw a Palladian uplift--a passage thrown out here, a few columns there, one extension wrapped round another, and yet further enlargements. The one extant print we have of Eastwell is of this eighteenth-century building (Nicolson 79; I'Anson 14). At the beginning of twentieth-century Myra Reynolds found a still further renovated version of this house which she called a "splendid mansion" set in a park on the North Downs with plenty of oaks, beeches, and yews. She thought the park was partly what it had been in the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries (from the contemporary Eastwell Blue Book) a cunning description of a rise called Mount Pleasant which she identified as the place which would become Ann's "lovely hill," dubbed by the family "Parnassus." The description is worth savoring as in it we can see that "Parnassus" was, for anyone interested in Ann Finch, strategically located: Mt. Pleasant is a circular eminence surrounded by ancient yet trees standing at internvals as solitary sentinels. From this point the view is remarkable. At our back is the wooded park with its undulations, its mansion, gardens and lake, with the tower of Eastwell church peeping up through the trees. On our left the horizon line is formed by Wye church and Wye Downs. Spread out before us are villages, parks, county seats, hop gardens, fruit gardens, orchards, cornfields, woods plantations, and meadows. In the distance we descry the coast town of Hythe, and on a clear day we may see the English channel with its passing shipping.One could have seen--and Ann saw from this hill--Eastwell, its church, Wye (in whose college Heneage and Ann lived for a few years) the downs, the villages, the ancient port of Hythe (to which Heneage fled in 1689), the Channel. But where Reynolds's mansion stood, one finds today a bourgeois hotel whose grounds are, alas, open only to the well-heeled "guest;" Eastwell church, in which Ann and Henage were buried, collapsed after World War II from damage sustained by anti- aircraft guns; of this church McGovern remarks, it "lies in ruins, the victim of a combination of war, neglect, and vandalism" (McGovern 66-7, 236n7; Physick 2-3; Buxton, A Tradition, 183). There is a certain irony in the truth that the only Eastwell left is the product of verbal musings by romantic scholars like Reynolds --and Gosse before her ("LW's Poems," 127-8)--because its park was the retreat of a woman who brought to the Finches a mere knight's dowry, and produced no children at all, and whose most poignant lines of verse derive from a deep recoil from the society of which Eastwell was a glittering prize, from a personal craving for quiet in solitude. Ann's allegorical take on Eastwell is in fact not quite Reynolds's or Gosse's; she rarely describes the house. For Ann, it's the park, and it's the park as an escape from a sycophantic corrupt society she cannot seem wholly to dismiss from her mind, as we see in her reiterated prayer for an "undisturb'd Repose," and "sweet Retreat," a place where Fate cannot touch her and "in the obscurest Vale" (from "The Shepherd and the Calm," 1713 Misc 116). The tone of this frame for her longing for Eastwell and charged poetry on its park may be seen in numbers of her fables; one she chose never to print, "The Jester and the Little Fishes," opens thus: Far, from Societies where I haue placeWhat a house needs is a dog like Snarl of "The DOG and his MASTER," who says he is right to keep the guests away: ... since to Me there was by Nature lent It is in the context of a recoil that Ann turned Eastwell park into an Arcadia where all is beauty, kindness, softness, peace; thus in very beautiful lines in the spring of 1703 in a poem entitled, "An Invocation to the southern Winds inscrib'd to the right honourable CHARLES Earl of WINCHELSEA, at his Arrival in LONDON, after having been long detained on the coast of HOLLAND, did she conjures the winds to bring Charles Finch back to the safety, as she saw it, of Eastwell park: Whilst Eastwell park does each soft gale invite, Ann sees Eastwell park as a place for kindly winds, singing birds, noble deer, a paradise of poetry; it was much more a linchpin in a country's central political network, which is how both elder and younger Heneage and most of the Finches saw it. For example, seven years before the younger Heneage was born, in 1648 it served as a rendezvous for Finch cousins, friends and their sons, servants bailiffs, labourers, and tenants to gather together with the leading gentry under the auspices of the second Earl to plan a revolt and sign an appropriate petition. Again and again cited for conspiracy to revolt, plots, attempted uprisings and downright riots between 1649 and 1659 are the second Earl and Charles Finch, the second Earl's second cousin (sixth son of that Cousin Heneage who became Earl of Nottingham, the workaholic and eternal Chairman to whom the elder Heneage had confided his dream). This Charles Finch and the elder Heneage's younger brother, a John Finch, were involved in an at first wild conspiracy known as Gerard's Plot (1654), which did lead to the most serious local insurrection of the Interregnum (Everitt, 279-86; I'Anson 55, 76) It was also no dream place for those on the side of Parliament or those people who had suffered under the casually exploitative nature of the upper class: the sequestration, forfeiture, and at times malicious and senseless ravaging of so many "malignant" houses during the Civil War shows how the lower orders really felt about their "local natural leaders" who were fighting to maintain control over them, and such a focal house and park as Eastwell (e.g., Everitt 112-3; 242-5). Since we have already described life in a middling or lower- middling gentry house such as Sydmonton or Maidwell, it remains only to say of Eastwell, there was not much difference between Ann's mother's or father's houses and his father's "greater" house. Gladys Thomson has studied the family papers of the Russells, Earls of Bedford, at Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire at mid-century. We find a world much like Maidwell: recorded amusements are dice, cards, the rare visit of a group of musicians during festival times, hunting, billiards, and yes, drink. The Russell volumes tell of a laborious and at times difficult and usually "soberly spent" life. The garden was there to grow food in, money is spent pragmatically and on prestigious trappings like velvet garments to wear, coaches, fancy saddles for horses and the like. The library in this house, along with the usual plethora of religious tracts, was moslty genealogies and "books with an anti-Roman bias; history, chiefly constitional treatise and works on the history of France and Rome; economics; a little on foreign travel; and some classics." There were no plays; very little verse (Spenser's Shepherd's Calendar is a rare exception). William Russsell, the fifth Earl of Bedford liked to get newspapers in too. (Thomson, Life in a Noble Household 37-81; 167-72; 226-79). In fact perhaps the only difference between great houses like Eastwell and Woburn Abbey and middling gentry ones like Sydmonton and Maidwell was Eastwell's history as one of the Finch centers for county and national political intrigue. Woburn became such a center in its later history; to this aspect of Eastwell we will return to when we deal with Heneage's and Ann's Jacobitism (e.g., the role of Woburn Abbey in the life of the later Russells, Schwoerer, see photograph, 175; Everett 245). The real Eastwell was also, as are all homes, a place for family intrigues; perhaps it was somewhat unusual in that the level of discomfort was such that it led to crises which reached the courthouse so often that when the younger Heneage finally inherited the property he almost lost it to creditors. The ordeal of litigation for him lasted no less than seven years; the last receiver was ordered by a court off the estate seven years later, and Ann died but ten months after the last creditor was excluded from payment. The source of much of this litigation originated during the elder Heneage's reluctant trip on the King's and Levant's Company's behalf to Turkey. While he was away, his heir, William, then Viscount Maidstone, was tricked, or so he said, into a marriage with a young woman, Elizabeth Wickham, who had what the second Earl thought a mean dowry; even worse, there had been no written contracts or settlements to preclude later long battles over more than one widow's jointure and more than one heir's claim. At first all five children were kept close to home. A letter tells us the parents left in October 1660; another that in 1663 William, age ten, and Heneage, age seven, were at Wye School in Kent (Cameron 39); located about a mile from Eastwell, next to Wye College, where Heneage and Ann would come to live in 1699, and founded by John Kempe, Archbishop of York, this school was then a kind of Dame school for all but the poorest laboring local children, boys and girls, to come to be taught to read and to write; the boys were also taught arithmetic; the girls, needlework. As mentioned above, to supplement this, the second Earl had also provided his boys with a tutor, Mr. Dodson and his wife. (Cameron 39; Halsted III, 173-5). But a year later the boys were separated. Heneage, age eight, was sent to a boarding school in Chelsea, perhaps with the same tutor (Cameron 39-40). Chelsea was then still a pleasant place, a kind of early suburbia. The boarding schools were converted great houses; it had a wide beach; thus does one contemporary describes it: The Sweetness of its Air, and Pleasant Situation, has of later Years drawn several Eminent Persons to reside and Build here, and fill'd it with a great Number of Boarders ... it has Flourish'd so extremely for Twenty or Thirty Years last past, that from a small stragling Village, 'tis now become a large Beautiful and Populous Town ... Its Vicinity to London, no doubt, has been no small Cause of its late Prodigious Growth, and indeed 'tis not much to be wondered why a Place should so Flourish, where a Man may perfectly enjoy the Pleasures of Country and City together, and when he Pleases in Less than an Hours time either by Water, Coach, or otherwise, to be at the Court, Exchange, or in the midst of his Business. The Walk to Town is very even and very Pleasant ...His day was roughly as follows: up at 7 in the morning and until 4:30 in the afternoon--punctuated periodically by prayers--at least one hour each of Latin and French, two hours of writing and drawing; map study or geography and cosmography; and accounting (Stone, Crisis of Aristocracy, 306-7). Heneage lived here between the ages of ten and twelve (Henning dates his stay as around 1665, II: 324). We can pause to imagine him a boy with hair down to his shoulder walking down to the water, book in hand. He'd be in shirt and doublet, a jacket with wing-like collar and long tight sleeves, originally tightly fitted in a V-shape, but by 1660 much less stiff and allowed to form itself round his upper trunk naturally. At the waist it flared dramatically or softly outwards, either over cloak-bag breeches or leaner smoother trousers to the knee, these latter were either "Dutch," loose and open at the knee, or "Spanish hose," high-waisted and long-legged closed off by ribbon or allowed to overhang his stockings. He'd have on leather shoes or boots with high squared tongues closed over by buckles or ties, gloves with gauntlett cuffs, and maybe carry a hat with a large brim, trimmed with a feather or ribbon. Rapiers were carried by small boys of even eight or nine; a boy of eleven would have a shoulder belt from which a sword would hang. In the middle of the 1670's when Heneage went to university, boys' clothes changed dramatically--no doublet, no collar, instead a "coat" a relatively loose garment fitted over a waistcoat, another similar sheathe, and under this a vest, the ancestor of the modern vest, except with sleeves and girdled with a sash (Cunnington, Children's Costume, 72-87; Payne 326-40). But we get ahead of ourselves. In 1668 Heneage returned to Wye and, with his younger brother, Thomas Finch, greeted his mother and father on their return from Turkey (Cameron 40). He had not been up to any serious mischief that we know of, but William, his older brother, had. |