|

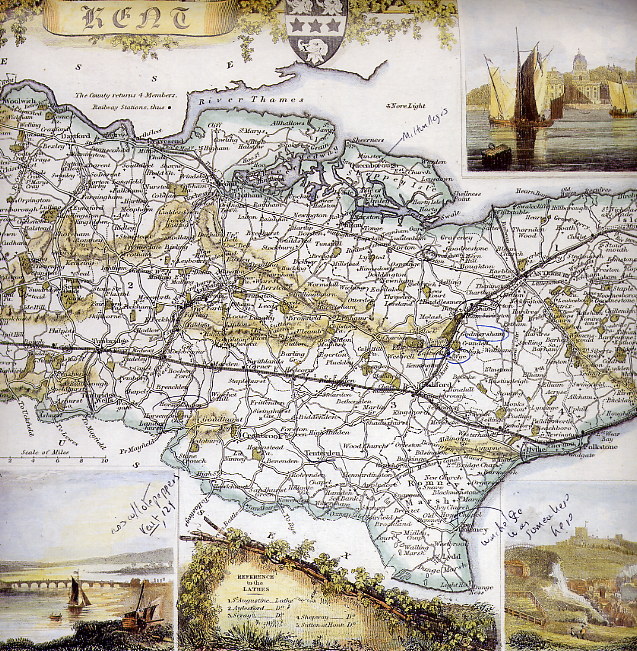

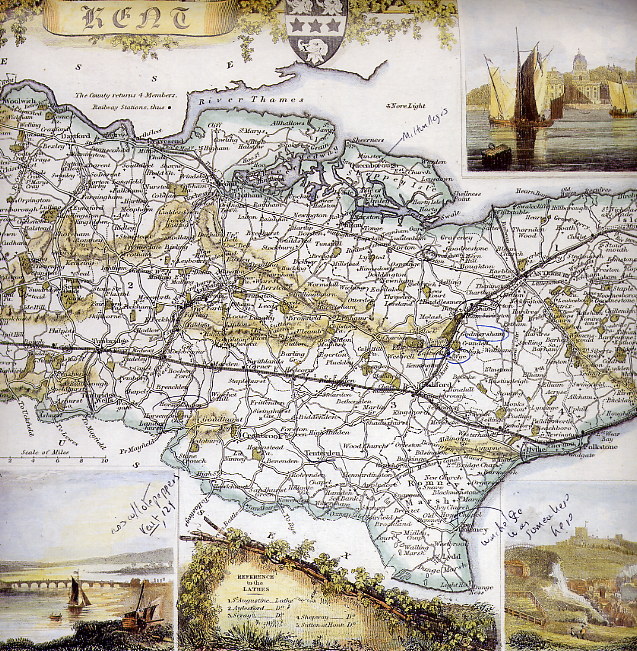

If it is not a truth universally acknowledged that like must marry like to forge a lasting marriage, it helps. Ann Kingsmill definitely married up when she became a member of a clan which claimed kinship with kings and queens, and which seemed accustomed to holding respected and powerful offices or influencing those who did. Nonetheless there was between the worlds in which she and her Heneage grew up a thorough-going likeness everywhere. There are first of all the parallels between their biological fathers. Like Ann's father, when Heneage's father married his mother, he was no longer young. In fact, in 1653 when the elder Heneage Finch and second Earl of Winchilsea--as we shall call him to distinguish Ann's husband, the younger or son Heneage from him--married Mary Seymour, this was his second marriage and he was well into his thirties. The second Earl was the eldest son of Sir Thomas (born 1578) and Cecilia Wentworth Finch, the first Earl and second Countess of Winchelsea. He was born in the early 1620's, and, as Viscount Maidstone, sent in 1633 to Emmanuel College, Cambridge. His father, Sir Thomas, died in 1639, his mother, Lady Cecilia, in 1642; three years later on May 2, 1645, he married Diana, daughter to the fifth Lord Willoughby of Parham, the "Governor of Surinam" who figures in Aphra Behn's 1688 tale of slavery in Dutch Guiana, Oroonoko; or, The Royal Slave (thus does he come down to us nowadays). Not much is known about Diana--by the early 1650's she was dead, with no issue--but she was not forgotten in the Finch family. The scuttlebut remained that her mother, a Catholic, was also mother to Aphra Behn (father unknown), and a half a century later our Ann is still asserting what the family wanted others to believed about "Mrs Behn:" she was Daughter to a Barber who liv'd formerly in Wye, a little market Town (now much decay'd) in Kent; though the acccount of her life before her Works pretends otherwise; some persons now alive Do testify upon their knowledge that to be her OriginalShe was not, in other words, as Mrs Behn's first biographer said, "a Gentlewoman, by Birth, of a good Family in the City of Canterbury, in Kent." These "persons now alive" were those who had known Diana or come with her--the guardian to Thomas Culpepper, foster-brother to Aphra Behn is a good candidate as he left the Willoughby estates to become steward to the second Earl upon the second Earl's first marriage (Goreau 12-13; but see Duffy 15-22). When the elder Heneage married the next time it was not to woman of a minor family whose trail of scandal was felt to be demeaning. Mary Seymour came from a powerful rich family with a heady genealogy. On the one side, she was a Devereux--her mother, and therefore our Heneage's maternal grandmother was Francis Devereux Seymour, a daughter of Robert Devereux, that second Earl of Essex who caused Elizabeth so much grief ("Devereux, Robert, second Earl of Essex," DNB 14:439). But it was the other side that was the real catch. In a footnote to a poem, "An Elegy. From the Muses at Parnassus (a Hill so called in Eastwell Park) ... , written after 1692 when Charles Finch, the elder Heneage's eldest son's posthumous heir, became the third Earl of Winchelsea, Ann points to one reason why the elder Heneage chose Mary Seymour. In the text of poem she remarks that the muses can "trace [Charles's] blood, until itt mix with Kings," and "Suffolk's Soul, reviv'd in [Charles] is seen," which statements she justifies at the bottom of her page thus: Ch Brandon Duke of Suffolk marry'd Harry the 7th Daughter Queen Dowager of France, One of his Daughters by her marry'd an Earl of Hartford, grandfather by the late Marques of Harford, who was restor'd by King Charles to the Dukedom of Somerset. He thus came from Harry the 7th's Daughter, and was great- gradfather to the present Earl of Winchilsea. To explicate: Mary Seymour was descended from the daughter and sister and uncles of kings. Mary Tudor, Henry VII's daughter, Henry VIII's sister, was first bartered as a pawn to the French Valois, i.e., married off to the aged Louis XII, who died soon afterward upon which she showed spirit enough to force her brother to accept her almost immediate marriage to a man she was in love with, Charles Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk. One of this Suffolk's daughters by Mary Tudor (to paraphrase Ann) married into the family of Thomas Seymour who richocheted into the nobility and power--and later out again--when his sister, Jane Seymour, presented Henry VII with a male heir, Edward VI; the many Seymour handles appear from 1537 on (Seward 35-9, 42-4, 81, 85; Smith, 19-20; Locke 2-94). The elder Earl had earned this one. By 1653 he had been and still was a leader among the Kent royalists--his other reward would be the Lord Lieutenantcy of Kent, given him as soon as Charles II began issuing new commissions (July 10, 1660). To enumerate: he marshalled, and provided troops; he personally fought bravely for Charles I; during the interregnum he risked sequestration and opprobrium by providing all sorts of supplies to Charles II during his travels--something Charles II also did not forget when it came to the second Earl's son Heneage. (McGovern 27; Everett 35, 278, 283-6, 303, 313-5; Twysden Lieutenancy Papers, 11; "Finch, Heneage, second Earl of Winchilsea," DNB 19:11-12). But Heneage's father and Ann's were not only both mature men-- with a similar devotion to "blood"--they both respected learning and wrote. This too and his loyalty to the Stuarts were factors in the elder Heneage's winning Mary Seymour's hand. Mary Seymour's father--and therefore the younger Heneage's maternal grandfather--was William Seymour, first Marquis and second Earl of Hertford and second Duke of Somerset (1588-1660). When he gave over his early romance and opportunism--he has come down in history as he who ran away with Arabella Stuart after which James I put her in prison and threw away the key--William Seymour demonstrated, as did the rest of the seventeenth century Seymours, an absolute loyalty to the Stuarts, and especially to Charles I. Among Seymour's many sacrifices and adventures on behalf of Charles I not least is to have been one of the four pallbearers of the coffin, not only a thankless but politically dangerous act at the time (Wedgewood 36, 153, 167-9, 203-5). He was among the lords who personally welcomed Charles II to Dover on May 26, 1660 (DNB, "Seymour, William, first Marquis and second Earl of Hertford and second Duke of Somerset," LI: 333-5). But in 1653 when the second Earl married this man's daughter, Hertford, as he was then called (his dukedom was declared forfeit in 1552), had for a time fallen from power, and was not about to win any plums from Cromwell or any parliamentary group. Still he had ample means, and many adherents who were, as it were, waiting this one out, and Heneage Finch, second Earl, with his Kentish network, was among those whose friendship Hertford now needed. For us it is important also to emphasize that Seymour or Hertford was, like his grandson, our younger Heneage after him, "by nature and habit a scholar rather than a man of action." A sort of coincidence links Ann and the younger Heneage even before they were born: it was to Hertford that Ann's father dedicated the manuscript of poems discussed above. According to Eames, by 1645 Charles I "had become uncertain of Kingsmill's loyalties," and Kingsmill was made to know this; since Hertford was a trusted friend to Charles I, Kingsmill prepared a manuscript of poems for Seymour as a step in a compaign to regain the king's confidence. In return for this poems (and probably other favors) Hertford engineered the knighthood from Charles I (Eames 129-30). Seymour's taste and aptitude for study has been mentioned by more than one writer; here we will take the Lady Arabella's word for it, as her comment brings us a flavor of the period: he was a man "'grave and serious ... loving his book above all other exercises ... and of studious habits,' finding the greatest wisdom among his 'dead counsellors'" (quoted by Locke, 105). The elder Heneage and second Earl was a kindred spirit-- marriages in the seventeenth-century were more about who your in-laws were than who you or your children went to bed with. Stuart loyalist, he was also an amateur scholar and antiquarian when the word "amateur" did not carry its present negative connotations. This is best seen in his behavior towards his sons and what those sons became. While in this period it was common for many aristocrats, especially those strained for funds over the civil war, to send only the heir to university, from Turkey (as an agent for the Levant company and ambassador for Charles II) he involved himself personally in sending one son to Cambridge and the other to a private school, and later back in Kent he sent his second and third son, and (by then fatherless) grandson all also to university. And he made sure that when the boys were young and he was in Turkey learning was really going on. For example, from Turkey again, he writes to the commissioners on his estate to make sure young Heneage has started Wye school and to look into the character of his tutor and the tutor's wife, Mr and Mrs Dodson; he thanks the Duchess of Somerset (Francis Devereux Seymour, the boys' grandmother we recall) for making sure Heneage attends school while the older William is off to Cambridge. Again he writes to give the tutor a vicarage rent-free; he sends his boys curios and things to excite their interest in antiquities (McGovern 27, 55; Cameron 40). There is extant a letter he wrote to another Heneage Finch in which he expressed his dream that his eldest son, William, become an able statesman and a scholar in the tradition of his correspondent and the Finch family. This Heneage Finch (1621-82), the cousin whose influence was another factor in gaining our elder Heneage his Devereux- Seymour wife--hereinafter Cousin Heneage and first Earl of Nottingham-- had a long and distinguished career as "a constitutional lawyer of the highest repute" from the period before the civil war into the 1680's; his was a life of "unremitting official and professional toil." More to the point, there was scarcely a committee on which he was not placed, often as chairman, and everyone testified to his "forensic eloquence" ("a handsome turn of expression" was the way a contemporary put it). Charles II rewarded him again and again (solicitor general, Lord Chancellor, first Earl of Nottingham). He was a good man to have on your side (Henning II: 317-22; "Finch, Heneage, first Earl of Nottingham, DNB 19:8-11). And tradition it was, for Cousin Heneage was the eldest son of a man who comes down to us as Sir Heneage Finch (1580-1631), the fourth son of the second Earl's grandparents, Sir Moyle and Elizabeth Heneage Finch (of whom more below), a younger brother to the elder Heneage's father and thus our younger Heneage's great-uncle. Sir Heneage had been a distinguished jurist who left a body of significant opinions on the law--and a beautiful monument to himself and his wife. Something of the nature of this man may be discerned in the words he left about this monument: I earnestly desire to be buried in Eastwell church in the vault where my most noble father and my dearly beloved wife together with the first pledge of our love our first sonnet lye all interred and where a poore monument in remembrance of my wife and myself is already erected The second Earl, our elder Heneage was a less of a central player than his cousin or great-uncle or father-in-law--he was someone important in local politics, a supporting player--much as his second son, the younger, Ann's Heneage would become. Such people are needed on the ground--as the axiom has it, all politics are local. Like the younger Heneage and Ann, he preferred the countryside of Kent to the London court mightily, and spent time writing about his personal concerns. The content and flavor of his two published works may be suggested by their titles: "A Narrative of the Success of his Embassy to Turkey. The Voyage of the Right Honourable Heneage Finch from Smyrna to Constantinople His Arrival there, and the manner of his Entertainment and Audience with the Grand Vizier and Gran Seignieur;" A numbers of private letters show the elder Heneage expressed himself ably and could use his pen to gain what he wanted. Much like Ann's paternal grandmother, Lady Bridget White Kingsmill (he and she would have understood one another) he was tenacious in holding onto to power and prestige over others; profit in this period was a fruit which took slow cultivation. Shortly after becoming Lord Lieutenant of Kent, he found himself "much to his disgust," forced, in the words of the editor of the papers of the Twysden family (another Kentish family with whom the Finches more than once intermarried) to "forsake the Kentish woods and fields for a post at Constantinople." In the midst of illness he writes letter after letter expressing an anxiety not to lose control over appointments; he seems particularly eager that the Kentish Militia (in which he later placed the younger Heneage) should not fall into desuetude through "divisions among themselves" and "underhand dealing." He waxes ominous over "that insatiable petitioner of favours from the crown," one Charles Stuart, duke of Richmond, and urges friends "to perswade" the deputy lieutenants in Kent "to an unity, that the common business may not through private piques receive any interruption." The tone in some of these suggest a man who could be pleasant when it suited him to be: thus to his cousin, Sir Roger Twsyden, he concludes an expansive letter ("I only assuring you They are persons of known worth, wisdom & Loyalty... Your trouble ... will very much oblige"): "Your very affectionate friend & servant WINCHILSEA" (Twysden Lieutenancy Papers 11-6) There is also a strong parallel between the lives of Heneage's and Ann's two mothers, despite the humbleness of the Haslewood ménage. Neither left a letter nor allow us to tell much of a story beyond a history of childbirths followed by death. Of Heneage's mother as an individual we can only say she bore at least eleven children and must have been dead before April 10, 1673 when the elder Heneage married for a third time. Shortly after her marriage to the second Earl, the babies had begun. William Finch, the heir, named after his paternal grandfather, was born before the end of 1653. Then Francis Finch, named after her paternal grandmother; Francis would marry Thomas Thynne, First Viscount Weymouth, and be a good friend to Ann (Cameron 81; Reynolds xxxxiv; Hughes, Gentle Hertford 471). Heneage was number three (this is not counting miscarriages, which there are hints of), born January 11, 1657. Before October 1660 when the elder Heneage and she went to Turkey, she had produced two more: Thomas about whom know only that in 1689 he was about 31, and so was born around 1658, that he married Anne Haydon, and that he died before she produced any children. Then there was Elizabeth or Lady Betty who died three years later (around 1663). Then in 1660 came the call to Turkey and William, Francis, Heneage, Thomas, and Betty were left, as custom decreed, in the care of the nearest maternal relative, the grandmother Francis, Duchess of Somerset, who came to live at Eastwell (Twysden Lieutenancy Papers 14; Cameron 39). One motive for removing Mary Seymour from five young children seems clear: the second Earl was determined not to lose any years of childbearing. His contemporaries called him "amorous," and in Turkey he was reputed to have "had many women" and "built little houses for them." On his return from Turkey in June 1668, Charles II remarked, "My Lord, you have not only built a town, but peopled it too" (Everitt 303n1). There are no extant records of illegitimate children, but the second Earl fathered at least sixteen children, and before he returned with Mary Seymour from Turkey, he wrote proudly of three more "Turkish" sons. So thus Mary Seymour's history in Turkey: first she gave birth to Leopold, born October 28, 1662; named after Emperor Leopold, he became a scholar; by January 21, 1686 he was warden of All-Soul's College, Oxford; and on November 4, 1689, prebendary at Canterbury. Then she had Lashly (or Leslie), to whom Ann wrote a delightful poem on a punchbowl; he married at age 30, Barbara Scoope, and died without issue. And there was Henry; in 1702 he became Dean of York (Cameron 39- 40, 64-5, 229, 237; Reynolds xxxiv). There are two further daughters, Mary and Jane, undatable, died unmarried, about whom nothing else can be said (Cameron 65; I'Anson 56). We hear she is in bad health--more hints of miscarriages. And this is all we can say of Mary Seymour but for one unpleasant confused rumor (Cameron 39-41; I'Anson 56). The rumor has to do with the woman's death, and it connects the elder Heneage to it, but in a form the era found more acceptable than the truth--which is that she died of too many pregnancies and childbirths in too few years. But thus Rumor, as written down by John Aubrey, and reprinted in the 19th century guidebooks on Eastwell: I cannot omit here taking notice of the great misfortunes in the family of the Earl of Winchelsea, who at Eastwell in Kent, felled down a most curious grove of Oaks, near his noble seat, and gave the first blow with his own hands. Shortly after, the Countess died in her Bed suddenly, and his eldest son, the Lord Maidstone, was killed at sea by a cannon-bullet The guidebook only infers how these events connect: the second Earl felled his oaks sometime in 1669 or 1670, and Rumor blamed not him but the wife for this and said that she and her eldest son, William, died, as a sort of judgement; that is, local superstition blamed this poor women for her own death; even more dismaying, in our Ann's poem to William's posthumous son, as we have noted, the third Earl of Winchilsea, Charles Finch, "Upon my Lord Winchilsea's converting the Mount in his Garden to a Terras ..." we find the distasteful insinuation that Heneage's mother used sex to seduce his father into destroying the trees: When by a Consort's too prevailing Art, To conclude: as Ann's mother was dead by the time Ann was three, so Heneage's mother left him before he was three, and when she returned died shortly afterwards. Neither of them appears to have had any time for a personal bond to form with a mother. Paradoxically, their families were also alike in their history, culture, and most important, the source of their wealth, pace any legends. "Paradoxically" because for all the talk of a "glorious history" for the Seymours and Finches, if we try to go back to the eleventh century where Finches located their progenitor, we find the same kind vague stories the Kingsmill liked to tell of their ancestors. One difference is on the Kingsmill's side: they were content to try to go back merely to the thirteenth century for a Hugo de Kingsmille [muln?]-- though it's a toss-up whether we accept Reynolds's version of a personal service done for King John for which first Kingsmill was granted a Royal Mill at Basingstoke, Hampshire; or Cameron's version of a deed dated 1277/8 citing "huge de Kingsmille" before the baiiffs at Basingstoke for alienating the mill without the King's licence (Cameron 29; Reynolds xviii). The Finches took their story all the way back to that famous year 1066, to France, to William the Conquerors's warriors; their fervid historian, Bryan I'Anson, lists among these one Herbert Fitz-Peter, descendent of the Counts of Vermandois; I'Anson dismisses the "ridicule" with which "certain historians" have regarded the connection between the Fitz-Peters and the Finches; first the Fitz-Peters turns into Fitz- Herberts and then these are connected back to King Stephen, and themselves turn into Finches when a Fitz-Herbert who has turned into a Herbert marries an heiress whose second name is Finch, which Herbert then begins to hyphenate his name with Finch. We are not told this woman's first name. I'Anson's argument also consists in part of of asking how the title of "Baron Fitz-Herbert of Eastwell" were conferred if there were any doubt. How indeed. In 1668-9 Charles II simply took it upon himself to reward the second Earl by making the genealogy the second Earl claimed official (I'Anson 15-20). But an art historian, John Physick tells a more recent and concrete story which is clearly attached to the specific forebears of the elder Heneage Finch. Physick takes us back only as far as that same early Tudor period which saw the rise of the Kingsmills. In the fifteenth century a Cornwall family called Moyle came to Kent. They began to acquire wealth through land when in 1537 one Sir Thomas Moyle became a member and later Chancellor of the "Court of Augmentations," which administered the monastic property seized by Henry VIII. He hunted down heretics zealously, and with his rewards was able to buy the estate of Eastwell from the daughters of Sir Christopher Hales, Henry VIII's Attorney-General. The Finches first enter the picture when Catherine Moyle, the daughter of Sir Thomas Moyle and his wife, Katherine Jourdain, marries a Sir Thomas Finch, a member of the then middling minor gentry of Kent. This man had distinguished himself on the battlefield and fighting at sea. This military Sir Thomas is our first individualized male Finch, and it was his help in 1553 in suppressing Wyatt's rebellion in Kent and consequent marriage to Catherine Moyle of Eastwell that brought the family Eastwell. But the Finches, as the repeated name of Heneage testifies to, saw as their founder a wealthy Elizabethan heiress, Elizabeth Heneage. Her contribution was twofold: vast monies and two titles. On November 4, 1672, in Heneage House, London, the home of her father, Sir Thomas Heneage, Elizabeth I's Vice-Chamberlain, Chancelor to the Duchy of Lancaster, the elder son of Sir Thomas and Catherine Moyle Finch, Sir Moyle Finch garnered the sole child to a man of enormous means with all the right connections. The rest is not quite history, but it falls into place naturally enough. In 1689 Sir Moyle Finch gained permission to enclose 1000 acres around the house and embattle it; Eastwell began to change from a relatively modest Elizabethan manor to a great house, a center around which the district could form itself. Sir Moyle and his Elizabeth Heneage Finch also produced eight children before in 1614 he died. |