Ellen and Jim Have a Blog, Too

We are two part-time academics. Ellen teaches in the English department and Jim in the IT program at George Mason University.

Seeking a social identity: the latest Oxford _Persuasion_ · 7 December 08

Anne Elliot (Amanda Root) lifting up her face to the fresh sea breezes & sun (‘95 BBC Persuasion)

Dear Friends,

Here I am (appropriately enough) alone to write of a book about human isolation imagined overcome, and recuperating a social identity—and the latest Oxford reissue of their edition of Jane Austen’s Persuasion. I regret to say Laurel felt herself unable to continue; for myself I felt unable not to, if only to complete this set of reviews of these early 21st century Oxford reprints, reissues, and reconfigurations of Jane Austen novels in the context of other editions, controversies over and interpretations of the texts, and the film adaptations now available on DVD1.

So, to the business, a review of recent editions, suggestive readings of the book, a survey of some controveries, and review of the films. This time I begin with the films and end on a general summing up of my findings about all 6 sets of editions I reviewed.

************

A tale of the pain and peril of human isolation not quite overcome, a modern book:

Anne Elliot (Ann Firbank, setting out in search of Mrs Smith in the less safe, old & decaying streets of Bath (‘71 BBC Persuasion, a film with many long shots)

Anne Elliot looking over old naval news as she closes down her home (‘95 BBC Persuasion, typical close up)

KateForster (Sandra Bullock), first full shot moving out of her temporary rental, (‘06 Warner Lake House, ghost-like wintry surface, continual patches of snow everywhere)

Anne Elliot (Sally Hawkins) directing servants, alone as she closes down Kellynch, first full still, most done just with this grey coloration and unsettling angle (‘07 Clerkenwell/WBGH Persuasion)

Persuasion. Better known and somewhat misunderstood as a story of reprieve & retrieval: joy snatched from a descent into ever-increasing age, illness and death.

Captain Wentworth (Rupert Penry-Jones) looking down at his long-desired life’s companion (‘07 BBC Persuasion)

Anne Elliot saying she is certain, very certain (‘07 BBC Persuasion)

But really a book of a revenant made human, of deep emotional pain & exhaustion:

A visionary sequence where Wentworth (Rupert Penry-Jones) appears to Anne (Sally Hawkins) as she plays Chopin’s “Death March” (‘07 Clerkenwell/WBGH Persuasion)

And we are invited to feel that Anne’s presence also burnt into Wentworth’s mind as he removes himself from her piano

Anne Elliot looking very worn, indeed haggard, emotionally drained from that country walk (‘71 Persuasion)

and of country walks and seascapes, flowing water:

We glimpse Henrietta Musgrove (Mel Martin) and Charles Hayter (Paul Alexander) led by Charles Musgrove (William Kendall) back to the waiting group at the top of a hill (‘71 Persuasion)

The Cobb, Anne and Henrietta (Victoria Hamilton) walking along, a boy passes (‘95 Persuasion)

including rain, umbrellas & a need for thick boots:

The well-armed Captain Wentworth (Ciarhan Hinds) offers his umbrella to Anne2 the thickness of whose boots have been attested to (‘95 Persuasion)

*********

The latest Oxford reissue3 (2008) is a good buy for the type book, a half-way house between the rich apparatus type books (Nortons, Longmans, Broadviews) and those which accompany the text with a minimal introduction or afterward (Signet, Barnes & Noble). It includes the appendix, “Austen and the Navy” by Vivien Jones found in the 2008 Oxford Mansfield Park, where Jones corrects and adds information ignored in Austen’s idealized depiction of the navy; and also Henry Austen’s biographical notice first published in 1817 with the dual posthumous edition of NA and Persuasion; and the cancelled chapters or Austen’s first version of an ending for Persuasion.

I assume many readers will immediately see the use of such an appendix, and importance of Henry’s biography (albeit brief and impossibly hagiographic), but might perhaps think these cancelled chapters are superfluous to anyone but the scholarly student of Austen. Not so. They contain passages which suggest how Austen might have worked the book up to three volumes had she lived: for example, the Crofts seem to know that their brother had been engaged to Miss Anne Elliot, and be working to bring them together4.

More: they have potentials for high drama clashes as well as comedy, and in both the 1995 BBC and 2007 Clerkenwell/WBGH Persuasions, two slightly differing strong scenes are created towards the ends of the films out of this first ending: both Nick Dear and Simon Burke chose to dramatize Wentworth’s (for him) traumatic agonized offering of Kellynch Hall to Anne on the supposition Anne is to marry Mr Elliot. They have textual authority for a Lady Russell acting with an arrogant hostile sneer reminiscent of her inner reaction (as recorded by Austen) when she was told that Wentworth had engaged himself to Louisa Musgrove, only here it is directed at Wentworth and makes him (but only momentarily) despair (the 1995 version) or feel a renewed repugnance (the 2007), and Anne (in the 2007) feel intense anxiety and distress at the misunderstanding Lady Russell is fostering:

Captain Wentworth offering her home back to Anne (‘95 Persuasion)

Lady Russell (Susan Fleetwood) coolly subrisive to the Captain accuses him of upsetting her friend (‘95 Persuasion)

Anne denying such unfounded rumors and asking the Captain (Rupert Penry-Jones) who has been responsible for them (‘07 Persuasion)

upon which the hard cold Lady Rusell (Alice Krige) enters, determined to interrupt them (‘07 Persuasion)

When in 1980 Oxford broke with the tradition of printing Northanger Abbey with Persuasion, they filled in the slender book with the cancelled chapters, and in 2004 added Henry’s biographical notice5. One might have hoped they would include James Austen-Leigh’s important 1870/1 memoir of his aunt’s life; but alas, they published this separately in 2002 with Henry Austen’s two different biographical notices, Anna Lefroy’s “Recollections of Aunt Jane,” and Caroline Austen’s “My Aunt Jane Austen: A Memoir,” edited by Kathryn Sutherland6.

How does this edition compare with others of the same type, the full apparatus and minimal editions? Deirdre Shauna Lynch’s introduction shows the latest trends in Austen criticism in emphasizing how the book’s time frame is overtly rooted in a specific time and place, between the capture of Napoleon and his escape, and reading it through historical lens; in line with the other Oxfords, feminism is now avoided, so (ironically) the introduction comes most alive towards the end when she moves to discuss Anne’s debate with Harville over women’s roles and natures but still remains muted.

As an introduction for most readers, Gillian Beer’s essay in the rival half-way house edition, the 1998 Penguin (reissued 2003) is much better. It’s much more accessibly written, clear and simple; while short, her essay adds a new insight that has begun to affect readings (and films): the novel may be regarded as a kind of dream ghost-like love story which dwells on the silent intensely rich life of the disregarded heroine (a “solitary island”); Beer praises Austen’s effective frequent use of free indirect speech as an attempt to create this world of subjectivity kept in check; at the same time she notes the signs of its unfinished state.

Since the text has been freshly edited with an attempt to hold closer to Austen’s spelling and punctuation, I’d have recommended this one over the Oxford, but that it lacks the cancelled chapters and biographical notice, and thus represents a sad falling away from the 1966 Penguin edition of Persuasion by D. W. Harding, which made readily available for an inexpensive price for the first time in the century James Austen-Leigh’s transformative 1870/1 Memoir of Austen, together with the penultimate cancelled chapter (but for the last paragraph the second cancelled chapter is almost exactly that of the final chapter of the book as presently published), and a long excellent essay by him on the novel and memoir7.

Among the minimalist editions, the Signet with Margaret Drabble’s introduction is yet another clearly-written insightful essay, and if the reader is not persuaded (pun intended) that the cancelled chapters, biography and other critical pieces are of service, there is an argument that Drabble’s edition (as in the case of her introductions to the Sense and Sensibility, Mansfield Park, Emma and Northanger Abbey Signets) is the best reading edition of Persuasion for the average reader. She edits sensibly (based on Chapman) and in her introduction discerns in Persuasion a new progressive outlook in the book’s inclusion of more fringe people, a new generosity of spirit towards the fallen and injured, a remarkable turn towards rooting experience in natural forces of all types and more & lower social worlds:

The old entrance to the Cobb in Lyme (‘71 Persuasion)

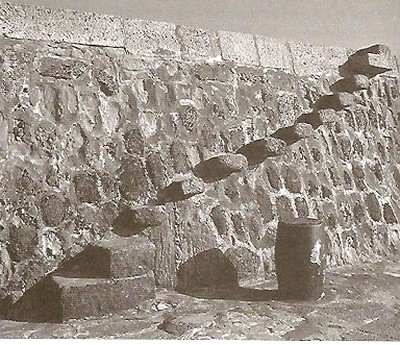

(The 1971 BBC Persuasion, which contrasts nicely with the modern idyllically renovated luxurious center of Bath. This is Bath as it was before the recent renovation, transformation, & modernization of the spa city: We are see genuine downtrodden streets, the houses still blackened as they were during much of Victorian times. The difference is such streets would have been filled with people. Here we see an unrenovated Cobb8.)

Unfortunately (as with the other new afterwards of this series), the afterward to Drabble’s Persuasion Diana Johnson’s piece is embarrassingly simple-minded and wastes pages: she was perhaps instructed to appeal to undergraduate composition students with an explicit numbering and description of Austen’s techniques that assumes Austen was writing consciously with a marketplace like our own in mind.

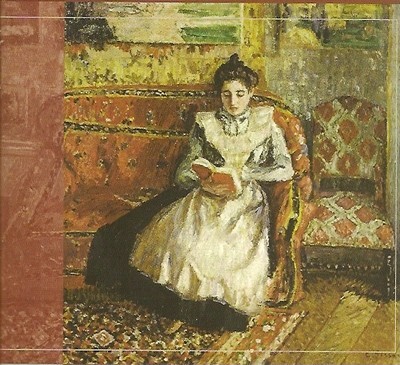

So if you don’t share Drabble’s political vision or reading of the book, the similarly minimalist (but still respectably edited and framed) Barnes and Noble 2003 Persuasion, introduced by Susan Ostrow Weisser may then be marginally better for you than Drabble’s. In lieu of the overtly dumbing down afterwards offered in the latest Signets, and like the other Barnes and Noble’s Austen texts I’ve reviewed9, there is a full note on the film adaptations, and a selection of little known unusual 19th century commentary. I particularly appreciated the excerpt from Sir Francis Hastings Doyle, which taught me where a fantastical elaboration of the rumor of Austen’s seaside romance came from: Mr Austen and his daughters are said to have been travelling through Switzerland and received the news of her lover’s brain fever on their way to Chamouni (resembling some of the recent books and films about Austen and Tom Lefroy). And the unashamed frankness of others: “Through [Persuasion] runs a strain of pathos unheard of in its predecessors” (from Scribner’s Magazine, 1891). Weisser provides a genuinely unidealized and persuasive account of Austen’s life; and she gives you an overview of the book which is sensible, readable, openly humanist and woman-centered. And the cover illustration is appealing too:

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), Jean Reading (c. 1860s)

There is a tradition in cover illustrations for Persuasion: picturesque scenes of Bath or a plain-looking grave young woman. Hence the picture that graced the green 1964 Signet (introduction Margaret Drabble), the first version of Persuasion I ever read—and loved dearly:

Mrs Anne Helena Hellichova by Joseph Hellich

The choice of Amanda Root and Sally Hawkins for the lead role in the two recent film adaptations follows this illustration history.

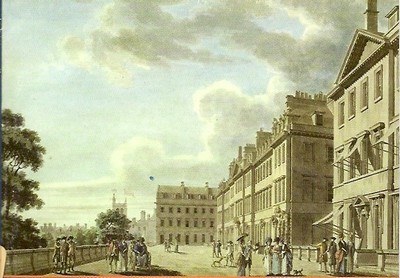

This tradition for covers is also followed in two of the full apparatus editions, both of which are excellent (and include the cancelled chapters called by Galperin the “original ending”) and offer picturesque scenes of Bath on their covers: Patricia Meyer Spacks’s 1995 Norton critical and William Galperin’s 2008 Longman Persuasion, e.g., from the Longman:

The idealized picturesque Bath of early 19th century tourist dreams

Although (alas) brief, Spacks’s introduction focuses us sharply on the book’s inwardness and (resembling Mansfield Park in this) sociologically-detailed and mapped text; she picks a excellent set of essays; A Walton Litz’s finely discriminated account of landscape in the novel; Robert Hopkins’s account of its modernity (its sense of chance, time) and how it reverses a number of attitudes found in Austen’s earlier novels (on first love for example); Mary Astell seems to sum up much that has been said variously; Claudia Johnson defends, and most interesting, Cheryl Ann Weissman writes of the book’s elusive schemes, in-depth and mysterious heroine & haunted fairy tale atmosphere.

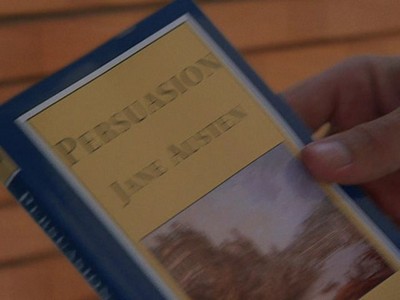

Perhaps deliberately, but probably by chance, it is this edition that Kate Forster left on a bench in 2008 and is sought for by her revenant (now dead) hoped-for lover, Alex Wyler (Keenu Reeves) as he passes unseen by her and another man:

Kate Forster (Sandra Bullock), herself a vision, passed by the ghost of Alex Wyler (Keenu Reeves) (‘06 Lake House)

The Norton Persuasion retrieved by Alex

This free adaptation (see an excellent summary) takes the implications of Austen’s tale back into at once firm probability and fantasy: the yearning couple are thwarted for the man has been dead for a couple of years (from an accident) by the time the story begins.

Galperin’s Longman Persuasion makes good choice of contemporary materials and reiterates his (perhaps provocatively startlingly and not really persuasive point of view in a short and much more clearly written (than his book) introduction to the Longmans. He makes his case more in his choice of secondary materials. Instead of the usual reprint of Austen’s letters to Fanny Knight about who to marry and the importance of love, he reprints letters by Austen during the hard time of choosing a place to live in Bath, and the few towards the end of her time there which register her dislike and the one letter from Lyme. There is also a long section of reviews.

If for nothing else, his choice of illustrations makes his book desirable. He makes visible to the reader the realities of the places Austen describes. For example, he reprints a contemporary print of Lyme:

A photograph of the Cobb and the granny steps. They don’t look safe:

Older photos of Bath before the recent renovations:

Sidney Place, which the Austens rented while Mr Austen was still alive

Finally, a third: Linda Bree’s Broadview edition. She breaks from the traditional covers to show us Montreal Harbour, c 1875, a photograph by William Notman. Her long introduction begins with some central unproven assumptions (“Persuasion” is the title Austen would have picked; it is essentially a finished book); however, her analysis of the extant text is so sensitive and insightful she provides much suggestion about what could have been elaborated out of the text we have: for example, Anne’s life “imprisoned in the wall of solitude and silence” is broken in upon unusually by Mr Elliot and thus she is strongly attracted to him; in a longer book, she might have spent time considering his courting of her seriously—and nearly made a common mistake, but not one the heroines were allowed before this book. It’s not that she now lacks “firm opinions” but that she lacks the “status and power” at Kellynch to give them “the authority they deserve” (pp. 25-27). Bree’s secondary materials include an annual register of naval and military events at the time of the book, and excerpts from the poems discussed in the novel.

The editions of Persuasion resemble those of Pride and Prejudice; although far fewer (because nowhere near the best-seller), they are basically books made by people deeply sympathetic to and respectful of the novel, prepared to try to make it available for all types of readers. Unlike Mansfield Park and Emma, there are no central burning controversies or faultlines regarding how to understand the book. Many readers who love Austen love Persuasion.

Myself I own 11 editions of the novel, and one version in French and one in Italian, plus one separate edition (Chapman’s) of the cancelled chapters10. At one time it was my favorite of Austen’s novels, despite its manifest flaws. Now I am (like Austen herself) a bit bothered by the heroine’s near perfection (which to my mind makes her submit to and validate what she should not, what nearly destroyed her), and I wonder whether this harmony is the result of its relatively unfinished state; she hadn’t the time for her usual gradual performance which (I agree with Virginia Woolf and many others since here) might have once again produced a book both disquieting and ultimately comforting.

On to the films. Although it is sometimes suggested that there are five film adaptations of Persuasion, a fair viewing of the 2004_Bridget Jones’s Diary: The Edge of Reason_ (screenplay by Helen Fielding and Andrew Davies, based on Fielding’s sequel to Bridget Jones’s Diary) reveals that while it has some allusions to Persuasion (taken over from the book, especially at the opening when Bridget follows bad advice), it does not have a plot-design which analogously follows that of Persuasion, and a number of the incidents are rather modelled on Pride and Prejudice (e.g., when Darcy rescues Bridget from a Thai jail), and the ending overtly like that of Emma (when Bridget stops Darcy from attempting to propose), with an allusion not to Austen herself but another Austen movie: the wedding ceremony of Mr and Mrs Jones with Bridget and Darcy standing by after which Bridget catches the bouquet is a repeat of the ending of Clueless where Cher and Josh stand by to watch an older avuncular couple marry after which Cher catches the bouquet. The recent mini-series Lost in Austen parodies the common device in Austen movies of imitating or alluding to one another rather than Austen’s book.

Above all, the mood of The Edge of Reason is wholly unlike that of Austen’s book or any of the other film adaptations, which in its timid way even the ‘71 film captures:

Anne Elliot and Captain Benwick (Paul Chapman) walk on the cobb, talking of poetry, (as in the ‘95 Persuasion) he about to propose (‘71 Persuasion)

Like The Jane Austen Book Club, Bridget Jones’s Diary: The Edge of Reason is a composite free adaptation.

Since I have written several times and extensively on the four adaptations11, and in my review of the Oxford Northanger Abbey, Lady Susan, _Watsons and Sanditon_ referred the reader to good sources on Bath (as Persuasion is a sister-book), I leave the interested reader to go over to these, & end this series of reviews by sort of rough summing up on the available editions of Austen in the last quarter century.

Overall, the Penguin editions of Austen’s novels seem to offer the most scholarly and revisionist texts of her novels. The Oxfords seem very reluctant to revise existing editions, and the principles followed here are still those of Chapman and are now re-canonized at great expense in the new Cambridge series. For the minimal type editions, Barnes and Noble is making a creditable alternative to the Signets12. The full apparatus editions are highly varied despite general editorial policies and in some cases one edition, say for Sense and Sensibility and Mansfield Park Broadview are the best (by Kathleen James-Cavan and Jane Sturrock respectively); while in others, if I had to chose, it would be the Nortons for Emma (by Stephen Parrish), Northanger Abbey (Susan Fraiman), and Persuasion (Patricia Meyer Spacks). How valuable each is depends on what individual has edited the book. Your choice also depends on what you want: for contemporary documents, the Longman and Broadview are to be preferred to most of the Nortons.

Then there are individual imprints, e.g, Alistair Duckworth’s 2002 “Casebook” for Emma for St.Martin’s/Bedford which contains the whole of Emma, plus excellent contemporary documents and essays, and the outstanding achievement of David Shapard, in producing an easy-to-use and read mini-encylopedia, The Annotated Pride and Prejudice (New York: Anchor, 2004).

The only danger I see in some recent presentations of Austen is some younger readers may be fooled by websites which suggest modern sequels are at all comparable or like Austen’s novels (Jane Austen Today) or imply these or the movies can substitute for Austen herself. It is also imperative that introductions to the novels be written in clear accessible English from a stance that is not hostile to the author’s readership. Hostility does not only take the form of scholarly disdain and condescension13, but places like Austenblog misrepresent Austen herself by a popular snide or snarky and often unexamined point of view, totally at variance with Austen’s genuine feelingful moods and comic seriousness, as for example here:

Mrs Crofts (Fiona Shaw) listens to Wentworth say he’ll have no women aboard his ship (‘95 Persuasion)

I hope I have not been guilty myself here of suggesting the movies can be replacements for Austen’s texts: I see them as works of art in their own right (as are some of the sequels) which enrichen our vision, help us read the novels more adequately.

From a scene where Kate and Alex discuss Austen’s Persuasion

Alex. Kate, have you read Persuasion?

Kate looking intently at him: What?

Alex. By Jane Austen.

Kate. “I know who it’s by. Yes … um … it’s my favorite book. Why did you bring something like that up? What would you bring it up?

Alex. A friend of mine gave it to me recently and I was wondering what it’s about.

Kate. Hmm. It’s wonderful.

Alex. Yah?

Kate. Yeah. It’s about … it’s about waiting … these two people they … uh … they meet, they almost fall in love, the time isn’t right … they have to part and then years later they … theymeet again and get another chance. Yeah. They don’t know if too much time has passed, if they waited too long … you know too late to make it work …

Alex. Why do you like it?

Kate laughs. I don’t know.

Alex. No. Don’t get me wrong I mean it’s beautiful.

Kate. No. It’s terrible.

Alex. It’s terrible … that terrible …

Kate. It’s terrible.

Alex. That is …

Kate. Yah, it’s just terrible.

Alex. This is a personal question for you. Have you ever been through anything like that.

Kate shakes her head no. When I was … uh … when I was 16 I was completely in love with this guy. He played guitar and I ran away from home and went to San Francisco so I could go live with hm … yah … he convinced me I had a beautiful voice and I had potential for becoming a singer.

Alex. I know San Francisco.

Kate. Yes. He was like my first love, probably my only one.

Alex. He must have been a great guy.

Kate. Well, I don’t know. He may have been. It didn’t last long enough for me to find out. Yah. The truth is I cannot even remember what he looked like …

Ellen Moody

Notes

1 I will, though, not try for a blog on the recent reissue by Oxford of their edition of Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho (now introduced by Terry Castle) in the context of Austen’s response to the Gothic as planned. For the other five, see Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Emma, and Northanger Abbey, Lady Susan, The Watsons, Sanditon.

The phrase for my title and first subheader comes from A. Walton Litz, Jane Austen: A Study of Her Artistic Development (NY: Oxford UP, 1965):155.

2 There are four film adaptations of Persuasion available on DVD today: 2 of the “faithful” or “transposition type: 1971 BBC Persuasion was produced and directed by Howard Baker, written by Julian Mitchell, production design Cecilia Brereton, costumes Esther Dean, starring Ann Firbank, Bryan Marshall, Basil Digam, Valerie Gearon, Morag Hood, Richard Vernon, Georgine Anderson, Marian Spencer; 1995 BBC Persuasion, produced by Fiona Finlay and George Faber, directed by Roger Michell, written by Nick Dear, costumes Alexandra Byrne, starring Amanda Root, Ciarhan Hinds, Susan Fleetword, Fiona Shaw, Sophie Thompson, Samuel West; 1 free adaptation: 2006 Warner Bros. Lake House, produced by Doug Davison, directed by Alejandro Agresti, written by David Auburn, starring Sandra Bullock, Keenu Reeves, Christopher Plummer, Ebon Mosh-Bachrach, Willeke van Ammelroy, Dylan Walsh; 2007 ITV (Clerkenwell in association with WBGH) Persuasion, produced by David Snodin, directed by Adrian Shergold, written by Simon Burke, production design David Roger, costumes Andrea Galer, starring Sally Hawkins, Rupert Penry-Jones, Anthony Head, Julia Davis, Alice Krige, Amanda Hale, Tobias Menzies, Joseph Mawle.

3 Simply a reprint or reissue of the 2004 book with cover slightly altered. And like the other reprints (S&S, P&P, MP and NA, Lady Susan, Watsons, Sanditon) we also get exactly the same supplemental materials: brief biographical note, bibliography, chronology, and (by Vivien Jones) appendices on rank and social status and on dancing. The notes are a reprint of the 2004 notes. As with the other Oxford reissues, the text here is the one prepared by James Kinsley in 1971 (an emendation of Chapman), and based on the 1817 posthumous first edition.

4 I am not unusual in thinking that we have a truncated and unfinished book in Persuasion. My study of my calendar revealed the planned trip to the theatre would probably have come off (with the possibility of a painful snub delivered to Captain Wentworth). See A Calendar for Persuasion; there have been a number of essays published on Persuasion, arguing (variously) that the book we have contains left-over unworked up threads (Mr Elliot’s trip, Mrs Clay’s anxiety over the gift to the post office, Anne not having an opportunity to inform Lady Russell of the truth two times), crude characterizations (Mrs Smith’s melodramatic long revelation of Mr Elliot’s villainy), and unexplained behaviors: why does Mr Elliot court Anne so assiduously if he is wealthy, why not warn Elizabeth of the danger of Mrs Clay. And so on. William H. Galperin takes these chapters seriously as a reasonable ending to Persuasion, using them to argue the book has been utterly misread in recent years and is unromantic and even anti Anne’s marrying anyone, see his The Historical Austen (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003):214-38.

5 Rawson’s introduction to the 1980 Oxford Persuasion is of interest as it is an effective close reading of the book which attempts to prove that there is not as much new in the novel as readers suppose. He shows the strong use of satire, harsh, and Fieldingesque in the language, the repetition of stylistic mannerisms found in Austen’s earlier books; he also discounts the romance and melancholy of the book. This is typical of earlier male scholarship and reveals that Galperin’s view is not as original as he wants readers to believe. Rawson’s arguments are much more convincing that Galperin’s whose jargon-ridden language and theoretical abstractions may intimidate but can’t prove a case

6 As in 2003 Oxford also chose to publish a freshly edited and brilliantly introduced edition of Austen’s satiric juvenilia and earliest (unfinished) novel, Catherine, or the Bower (1993, edd. Margaret Anne Doody and Douglas Murray), alas not reprinted since, there seems to have been a plan to reconfigure Austen’s lesser known works and contemporary secondary materials by the simple expedience of putting NA in one book, Persuasion in another_, and Austen-Leigh’s Memoir as the lead text of a third. Sutherland’s essay on the family censorship of Austen’s life events and letters anticipates her recent book, Jane Austen’s Textual Lives, from Aeshcylus to Bollywood (Oxford UP, 2005).

7 D. W. Harding’s Penguin is arguably the best cheap buy in the used book marketplace for Persuasion because of the presence of this memoir, his perceptive essays and the inclusion of the penultimate of the Austen’s two cancelled chapters (only the first differs in essentials from the second and as it turned out final version of Persuasion).

8 The 1971 Persuasion differs strikingly from other early 1970 Austen films I’ve seen as well as a couple of other costume dramas I’ve seen: it attempts to capture this new open spirit through making visible Austen’s own new rooting her fiction in landscape, time, and change. Much of it is photographed on location and the streets of Bath. Since they had 225 minutes, they were able to lavish time on the country walk, less but enough on Lyme and the Cobb, and then (like other earlier adaptations) because they followed the balance of Austen’s novel, and included as much city & social life as she does (recent adaptations decrease the amount of city or town and social life a lot), the possibility which they took advantage of of showing different parts of Bath.

9 I described Amanda Clayburgh’s refreshing introduction to her Barnes and Noble Mansfield Park, and comments on the film, but neglected her choice of 19th century voices, 3 of which were sympathetic to the novel and heroine, the fourth by Macauley (about the book’s realistic typology) and fifth by William Dean Howell. The cover illustration is also (like that of Weisser’s Persuasion) well-chosen:

10 For Persuasion I own Jane Austen, Persuasion, trans. Andre Belamich, note biographique de Jacques Roubaud. Paris: Christian Bourgeois 1979; and Persuasione, trans.Natalia Rosi, introd. Pietro Meneghelli, in Jane Austen: Tutti e romanzi, ed. Ornella de Zordo (Rome: Grandi Tascabili Economici Newton 1997.

11 See The 1971 Persuasion: On location; Persuasion 2007_ and the latest Austen films; The compleat Persuasion: 1971, 1995, 2007; David Auburn’s Lake House and Post-feminism as refuge invention.

12 Despite the Everyman offering a foundational apparatus with each text (beyond the introduction, a full chronology), they fall into the third kind of text, minimalist. They don’t offer notes nor appendices. I have not gone over them individually because I do not buy them as they are more expensive than the Signets and (nowadays) the new Barnes and Noble series.

13 Some of the matter in the various editions I have gone over have also condescended as well as offered false information on behalf of an agenda (e.g., Claudia Johnson’s Norton Mansfield Park). I have pointed out where I could which introductions are written in stilted and unnecessarily difficult and abstract language.

--

Posted by: Ellen

* * *

Comment

- From Judy:

Thank you for sharing some of your thoughts on this [2007] Persuasion – I’m drawn by the idea of Wentworth as a revenant and the ending as a dream (I think happy endings can often be seen as dreams, as Charlotte Bronte says at the end of Villette. Let them picture union and a happy succeeding life.) I would like to compare with the other versions.

I have seen The Lake House twice but didn’t pick up on the echoes as much as I would now, after reading your blog on it ... the beginning of Lost in Austen was the best bit and I definitely thought Ritson was just right as Edmund in Mansfield Park."

— Elinor Dec 7, 11:16pm # - From Catriona Hall on Janeites:

“This was really helpful, been looking for Anna Lefroy’s Recollections for ages.

Also enjoyed the consideration of all the editions, a comfort to know that someone else has multiple copies, not tax deductible either as my career does not depend on them.”

— Elinor Dec 9, 9:05am # - Thank you to Catriona. I really appreciate the comment. I meant to be helpful.

Beyond that, I'll add that I was impressed by A. Walton Litz’s analysis of the novel. It was he who suggested reading the novel as about recuperating or seeking (inventing?) a social identity would bring together some of the various readings of the book. William Galperin has argued the romantic view of the book is all wrong; he’s extreme but if you see him as an extreme of Litz’s view, his point fits in, and his volume does contain Austen’s own letters which show her family painfully seeking an affordable place in Bath that would not make them too obviously fringe people and thus outside the circle they wanted to be part of.

Ellen

— Elinor Dec 9, 9:09am # - An addendum: Janet Todd and Linda Bree have written a “Commentary” article in TLS for December 5th, pp. 14-15. It's on JA's later manuscripts, and anticipates their coming book, The Late Manuscripts of JA.

They begin with the playlet, Sir Charles Grandison and argue it's not by Jane Austen and was perhaps after all by Anna Lefroy when young. Margaret Anne Doody and Jocelyn Harris have come to the same conclusion, Doody in an article where she showed the vacuousness of the text, and how even in the earliest Juvenilia Austen displays a mind examining things, critiquing, and when young especially a strong spirit of harsh satire and iconoclasm. For what it’s worth I agree: Sir Charles Grandison, the playlet is singularly empty of any content that could be at all called offensive by anyone. This is important since attention has recently been paid to the play, an edition was done by Southam where he accepted the attribution, and there is a film adaptation.

Then they move on to the poem on the Winchester races written the day before she died and the prayers. They argue the poem is genuine; surely, no one doubted this as it’s mentioned by Henry Austen. It is sophisticated verse couplet art and is savagely ironic so perhaps it was doubted. How could a dying woman write this?

They argue the three prayers attributed to Austen are not in her handwriting and so at least copied down by someone else. The handwriting of one is her brother, James's, so they suggest he wrote one during his illness. The attribution comes from a faint line by Charles Austen on one of the prayers.

As to the commentary on the relatives, they are discreet and say the relatives saw themselves as protecting Jane Austen's reputation, not their own.

E.M.

— Elinor Dec 11, 4:52pm # - From Vic:

I have followed your blog and meant to leave a comment on your review of Persuasion, which was a marvel … ”

— Elinor Dec 25, 8:58pm #

commenting closed for this article